Publication Background

Photographic historian Josef Maria Eder states that in the German countries The Photographic Society of Vienna was the:

“oldest organization of its kind”. It was founded in 1861 by the Friends of Daguerreotypy, who met in 1840 at the home of Karl Schuh, in Vienna. The founders were representatives of professional photography and men of science and art. Regular meetings provided contact between the members of the circle, who kept themselves informed in this manner about the progress of photography at home and abroad. Small exhibitions and a Wanderalbum (circulating portfolio), which was also sent to the provinces, propagated interest in photography in wider circles.” 1.

In Vienna, exploration of the new invention of photography in Europe began almost immediately after Daguerre’s invention one year earlier. Eder states the “development of artistic photography was in a great measure due to the amateur photographic societies formed during the last decade of the nineteenth century, especially to those at London, Vienna, and Paris. The first of these amateur societies in a German country was the Club of Vienna Amateur Photographers, later called the Vienna Camera Club.” 2.

By the first year of publication, the Vienna club had already staged two successful international photographic exhibitions, so the issuance of the Wiener Photographische Blätter made logical sense in terms of cementing their achievements and promoting further discourse. Contemporary writer Manon Hübscher explains:

“the International Exhibition of Photography held in Vienna in 1891 paved the way for the Club’s success, enabling its dazzling and almost immediate elevation to the status of a model.” 3.

“The Wiener Camera-Klub was also intent upon establishing itself as the leader of a growing movement in Eastern Europe. To this end, it provided a showcase for its work by issuing a magazine entitled the Wiener Photographische Blätter.” 4.

Hübscher says the publication “was designed to encourage the sharing of views and experience. It was both a practical tool for internal communication and a means of disseminating the Club’s work abroad.” 5.

The Wiener Photographische Blätter survived for five years: 1894-1898. Eder states:

“This organ was supported by substantial contributions from wealthy amateurs, but it ceased publication after a few years.” 6.

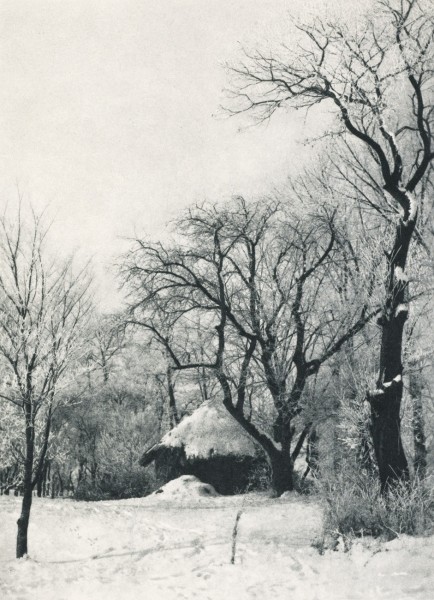

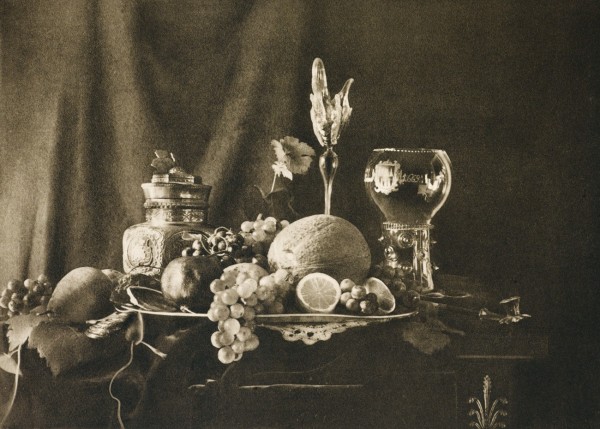

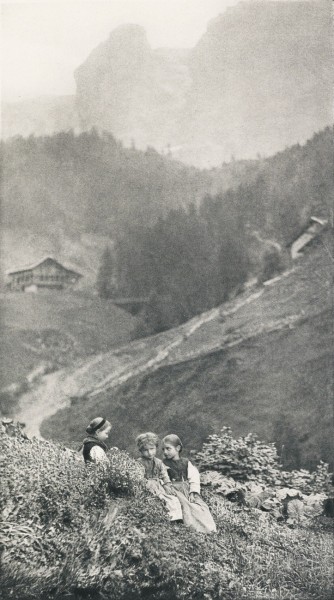

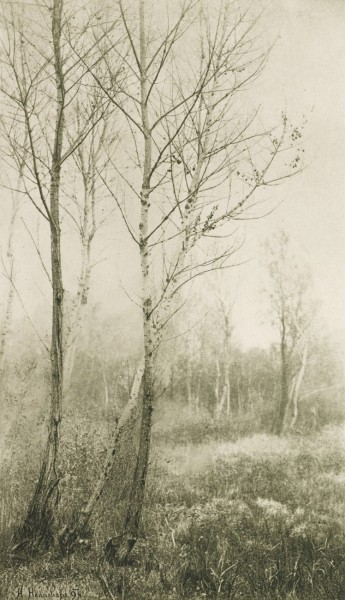

The journal “devoted itself especially to the artistic side of photography and was notable for its beautiful illustrations.” 7.

In America, Alfred Stieglitz was certainly intrigued with the journal’s publication. Contemporary writer Weston Naef writes:

“In January the first issue of the Wiener Photographische Blätter appeared, edited by F. Schiffner and published by the Camera-Klub in Wien with seventeen original photogravures by Hugo Henneberg, Hans Watzek, F. Mallman, J. S. Bergheim, and Adolph Meyer. Each gravure was printed with an ink of a different tone, and some like Meyer’s were mounted on colored paper, making this among the most carefully produced photography periodicals published anywhere in the world.” 8.

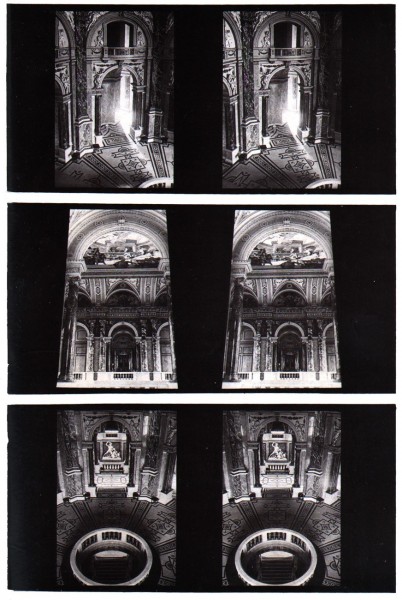

Naef’s reference to the journal’s issuance of 17 original photogravures for the January issue would most likely need to be amended however, as the entire year of 1894 featured a total of 21 photogravures, (16 being chine-collé gravures) two collotypes and a gelatino-chloride print of three stereoscopic views by Eduard Marauf.

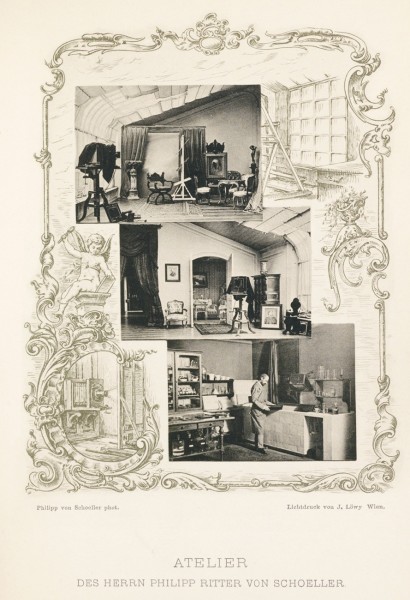

For the first year of Wiener Photographische Blätter, the majority of the copper plates for the photogravures were etched and impressions hand-pulled by Viennese copperplate engraver J.Blechinger, the son-in-law of Victor Angerer. Alfred Stieglitz would have been suitably impressed by their quality. In addition to having his own work published in later issues, (4 total) the journal would later influence his own business venture with photogravure and more profoundly, as a standard to emulate when he issued photogravure plates as editor of Camera Notes and later his own journal Camera Work (1903-1917).

Notes:

1. Josef Maria Eder: History of Photography: Translated by Edward Epstean: Columbia University Press: New York: 1945: p. 681

2. Ibid: p. 684

3. Manon Hübscher: The Vienna Camera Club-Catalyst and Crucible: in: Impressionist Camera: Pictorial Photography in Europe, 1888-1918 : Merrell Publishers : 2006 : p.125

4. Ibid: p. 126

5. Ibid

6. Eder: p. 685

7. Ibid

8. The Collection of Alfred Stieglitz: Fifty Pioneers of Modern Photography: Weston J. Naef: The Metropolitan Museum of Art: 1978 : p. 30