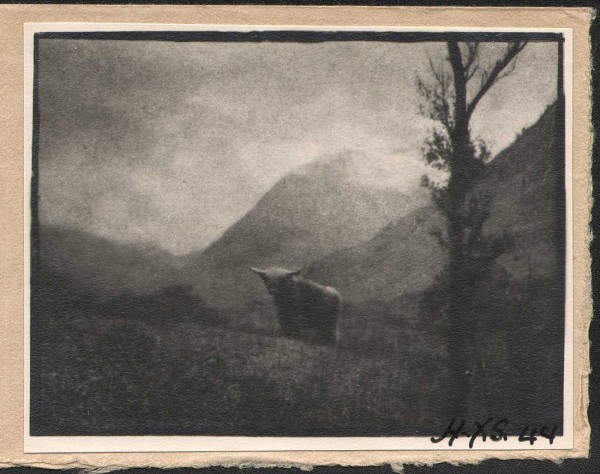

Cow in the Scottish Highlands ✻

PhotographerH.Y. Summons

CountryEngland

MediumGelatin Silver

EphemeraHoliday Cards

Year1944

View Additional Information & Tags

Animals, Cattle, Farming: Cattle, Fog, Landscape, Mountains, Supports

Dimensions

Image Dimensions: 7.9 x 10.2 cm (glued on margin of verso to window opening)

Support Dimensions: 17.2 x 22.5 cm (folded sheet of laid Japan paper) | 8.6 x 11.3 cm (window)

Little is known concerning the life of British pictorialist photographer H.Y. Summons, including his dates. (1.) However, an appreciation of his work by Sigismund Blumann, a friend and correspondent who edited the American west-coast journal Camera Craft was published in 1925. Summons is known to have been an authority on the making of paper negatives, (2.) and unlike many amateur pictorialists who engaged in other pursuits after WW1, he continued his photographic art and craft into the mid 1940’s, (3.) as evidenced by this fog-shrouded study of a cow, most likely taken in the Scottish Highlands and dated 1944, which he sent to Blumann. The miniature work is elegantly presented within a folded sheet of laid Japan paper with the front of the “card” bearing a pasted label printed with salutations: “Greetings for Christmas and the New Year from H.Y. Summons.”

Summons was winning awards for his work as early as 1906 (Photographic News quarterly competitions) and exhibited internationally; two examples being the 1907 Southampton Exhibition in England and 1909 Fifth Annual American Salon in Chicago.

The following in its’ entirety is the appreciation written by Blumann which also quotes from a personal letter Summons sent to the Camera Craft editor:

H. Y. Summons

and Some of His Work

An Appreciation by Sigismund Blumann

With Reproductions from Original Prints

by Mr. Summons

Not since the days of Robinson has photography had exemplars of control to equal that achieved by Summons of Virginia Water, Surrey, England. Others have dodged, worked, double-printed, and faked with more or less obviousness and with greater or lesser artistry but a print by this master exemplifies the finish of an artist and carries that peculiar domination that only genius can create. We are not trying to be fulsome over the pictures reproduced herewith but base our opinion over a period of years and the viewing of many prints at various times and places, — the opinion of an amateur — of one who loves pictorial photography for its own sake. The reader will be captivated by a poetic grace which in no way weakens the breadth or virility of these pictures. They deal in masses of light and shade: Strength is in the quantities of these. The quality of composition,line, and sentiment furnish the emotional appeal. There is no catalogue of attributes of Nature and Her beauties here: Rather, let us say, a sum total of all that environment and mood brings to the sympathetic soul when placed as Summons found himself when he made his picture in the open.

How much after-manipulation entered into the printing does not interest us as picture lovers, though we are glad to know the ways and means from a materialistic spirit. The prints are from paper negatives. The stipple, unique and wholly charming in Bromide, though common enough in Bromoil, is due to the texture through which the light must pass to act on the sensitized emulsion. It will be noted that this granularity is not obtrusive and like all that Summons does, has a definite reason and effect on the whole. We offer our readers the collection of little masterpieces with the assurance that they convey much that will profit and everything toward a great enjoyment.

Quoted from a Letter

Photography was taken up so long ago that the actual year is forgotten, but I was staying with a friend who was not in the best of health and as he had no hobby or interests he became very self centered: So I suggested he take up photography, which he did. As neither of us knew anything about it, he got a Kodak and the local chemist developed the films, telling us how our errors had been made, and, as we kept full notes of our exposures and did only subjects that could be repeated we made rapid progress. Then the chemist suggested that we do our own developing and told us our mistakes in that, and again progress was made, not only photographic but, my friend finding a new interest in life, physical progress. Then I bought a second-hand half-plate camera, but before I had an opportunity of using it I accepted an appointment under a German heart specialist and went out to Bad Nauheim for the season. During this first visit I realized the camera was too large to use comfortably but some of the negatives made then were ultimately converted into exhibition pictures, and this in spite of the fact that I had been using a camera less than a year and that I had never had a proper dark-room to work in. Developing used to be done at night, often the plates were put into a very weak solution as I turned into bed and on waking up at any odd time were transferred to the hypo! Casual in the extreme and not to be recommended. Sometimes the negatives were solid black masses, sometimes just as thin, still the subject was there and that well arranged — composition seemed to be a natural instinct — so that when I had lessons in making enlarged negatives, some two or three years later, these excessively bad negatives were in the hands of my instructor capable of producing excellent results, one being hung at the London Salon that autumn and in the following year was given a bronze medal in the International Exhibition at Dresden. I have forgotten the date but it must be nearly twenty years ago. This success set me exhibiting and I have kept it up ever since more or less successfully: More successfully abroad, less so at home, because for some reason unknown to me my work seems less appreciated here than out of England. As it is done purely as a hobby and for my own amusement it matters little if it be liked or not.

As I have already said, my camera was too large and cumbersome to be used anywhere and I decided to have quite a small one. Now all my work is done on films 2⅜ x l¾ inches which allows my instrument to go anywhere that I go and is no weight in the pocket. From these small negatives enlarged ones are made of paper, paper also being used for the transparencies as this method overcomes the too photographic appearance of the final prints which should be pictures firstly and photographs only secondly. Many people make photographs pictorially whereas I prefer to make pictures photographically. A picture should be a picture primarily and finally. Whether it be an etching, photograph, or painting a picture should convey it’s own message, be it to tell a story or to create an emotion just as a piece of music should teach its hearers without being described on a program. From this point of view I have avoided and shunned abstract titles. Captions should be unnecessary. Unfortunately so few people bring a complete understanding and sympathy to a picture that a title is often necessary even if it is only “Sunlit” or “The Letter Writer”, to take two examples from the catalogue of a recent London exhibition. The blame is not to be put upon the artist but is rather attributable to the public. (4.)

✻ title of work supplied by the PhotoSeed Archive, based on an educated guess of geography and subject matter assuming photograph taken in Great Britain.

print details: recto: in black ink lower right corner: H.Y.S. 44

print details: verso: written in graphite: 63

provenance: Sigismund Blumann; by descent to his grandson

notes:

1. The Getty Museum in California states 1904-1962 however it might seem the earlier date may have been when he first began exhibiting work.

2. see: “Paper Negatives for Pictorialists” by Sigismund Blumann: Camera Craft: Feb. 1930: pp.64-68 (illustrated)

3. among other examples dating from the 1920’s and 1930’s, two late gelatin silver works by Summons are held within the Paul L. Anderson collection at the Center for Creative Photography archive at the University of Arizona: The walls of Penne (1939) and N. Wales. (1945)

4. Camera Craft: A Photographic Monthly: San Francisco, Feb., 1925 pp. 55-60