Enoch Arden

PhotographerCatharine Weed Barnes

CountryUnited States

MediumCollotype

JournalThe American Amateur Photographer 1890

AtelierE. Bierstadt Artotype Printing Works (New York City)

Year1890

View Additional Information & Tags

Allegorical, Furniture, Genre: Men, Genre: Women, Homes, Illustration, Interiors, Old Age: Men, Old Age: Women

Dimensions

Image Dimensions: 15.7 x 12.4 cm November

Support Dimensions: 23.4 x 15.7 cm

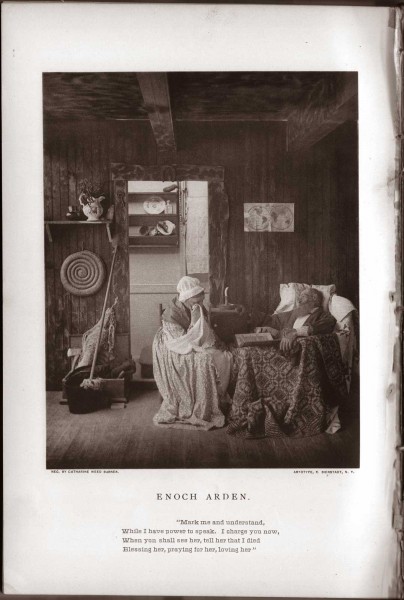

“Mark me and understand,

While I have power to speak, I charge you now,

When you shall see her, tell her that I died

Blessing her, praying for her, loving her” …Enoch Arden

The following editorial comment for Enoch Arden appears in the November, 1890 issue:

Our Illustration.

WE GIVE this month the third and final picture of Miss Barnes’ ” Enoch Arden” series. The picture represents Enoch in the cottage of Miriam Lane, after his return from the happy home of Philip and Annie. The originality of pose is striking, and by many this will be regarded as the strongest picture of the series. (p. 411)

In the September, 1890 issue of The American Amateur Photographer, under her regular column Woman’s Work, Catherine Weed Barnes discusses the fascinating and complicated process of making the series of photographs illustrating the 1864 narrative poem Enoch Arden by Alfred, Lord Tennyson:

An Amateur at the Washington Convention.

By Catherine Weed Barnes.

IT WAS suggested to me late last spring that it would be well to enter the professional competition at Washington in August, for the ” Enoch Arden” prize. Finding that amateurs who paid their dues to the National Photographic Association of America could compete with their professional brethren I entered the Association and received the circular of regulations. As expressed in my July editorial the subject of illustrating poems has a wonderful fascination for me. I began the preliminary study of the poem with an earnest zeal which led me to write the above-named article. It seems to me, now the victory has been decided, that it may be of interest to other amateurs to learn how one of their number prepared for such a contest. It was more through a hope of gaining valuable help in an advanced department of the school of experience than from any idea of eventual success in winning the prize that the work was undertaken.

These were gained, as they could not fail to be, but the prize, as is known, went elsewhere. Many hours of thoughtful study were spent in selecting the lines which, it seemed, might best express the poet’s ideas to one who, perhaps, might not have read the poem or scarcely remembered it. Those lines were quoted in last month’s number, and will appear with the proper pictures in this magazine, beginning with the September number. Passing over the childlife of Annie, Enoch, and Philip, which I did not think could be used when only three pictures were allowed, I decided on the early married life of Annie and Enoch for the first picture. It did not seem correct to take fragmentary scenes without proper connection, and then, to be consistent, I was obliged to include only such lines as required little, if any, outdoor scenery. Much searching of books of travel, magazines and art works aided me in designing the scenery and costumes, and then the sitters had to be carefully chosen. Believing that in what artists call a “picture” painted or simulated effects should, if possible, be avoided, I had a carpenter make me a wooden framework covered with painted boards such as would naturally form the walls of an English sailor’s cottage.

Everything was to be extremely plain, from the rag carpet to the old-fashioned table and dishes, while the bird-cage hung in the passage-way, and Enoch mended his nets over the half-open door, watched by Annie inside the room as she mended her husband’s socks.

A sailor’s costume was easily planned, but Annie’s must be of some soft clinging material, inexpensive and made in the style of a century ago. Ordinary sateen and home sewing accomplished this, and all of the other accessories were meant to express the surroundings of a happy, simple married life.

The day set for the sittings proved stormy, but by 6 A.M. I was out in the studio putting the last touches to the scenery and thinking of different poses. After breakfast posing began and before noon eighteen exposures had been made without any help to fill plates, adjust the heavy camera stand and generally make life easier. After development with pyro and soda, which in this, as in the subsequent work, was slowly and carefully done, the negatives were all laid aside for future selection. None of them were in any way retouched and the average exposure was ten seconds.

The second picture was the hardest of all to conceive and execute. The scene selected was where Enoch, returned, sees, through the window of Philip’s home, his beloved Annie watching her babe on its father’s knee, while his own children stand looking on, a happy family circle. The light from the room into which he gazes, shines on Enoch’s weary, sad face, and that which would have fallen on the ivy-covered wall and crouching figure was curtained off, confining all but a few rays of light to the interior of the room shown through the half-open window, it being night when Enoch sought Philip’s home.

After careful consultation with Mr. L. W. Seavey. he made me the wall and window, but the ivy and branches that nearly covered it were natural growths and the turf and gravel in the foreground came from the garden about my studio, the former being laid on zinc to protect the floor from dampness. Great care was needed to properly place the little furniture the room could hold and in arranging the group of several grown people and a five-month’s old baby. It was not easy to procure proper subjects, devise costumes, or manage to focus on sitters placed in anything but a straight line and have every one and everything in proportion. It was another struggle to have the inside group just enough visible to appear natural, but Enoch, as the important fact of the picture, required the greatest care in treatment. Of the two dozen exposures made that hot day all but one were rejected for some slight defect. It was necessary several times, in making this and the other pictures, to pose myself in the required attitude before the sitter caught the idea I wished to convey.

The studio is nearly twenty-three feet long, but so much was taken up by the scenery that I had to build out a platform from the front door, and a frame-work covered with non-actinic cloth, so as to run my camera-stand several feet outside the building. In this and the last picture I had some one to change plates and help with the heavy work, but not with the arranging or posing.

The last picture was the first taken, and the wall of Enoch’s room was made of rough boards stained and defaced by age and hard usage, while the doorway partly revealed an old staircase. Everything was intended to sharply contrast with the comfort and abundance of Philip’s home. Overhead, shutting out the top-light of the studio, was a timbered ceiling made under my directions by a carpenter so as to have the room appear, as it naturally would, dim and shabby with all the light coming from the side. This scene, also, required several exposures.

Then came the work of final selection of the negatives for the three best ones. I took the latter to the gallery of a professional friend, my own not having conveniences for such large work, the negatives being 11x14. There I spent a day in printing and toning the selected pictures. He then mounted, framed and sent them to Washington, whither I followed them some days later.

It is needless to say that the benefit of comparing one’s efforts with the work of those who are supposed to be thoroughly proficient is worth much to those who sincerely desire to improve their work, and I, personally, feel confirmed and strengthened, if that were needed, in my love and interest in camera work by my Washington experiences. They also taught me, and I wish to impress this strongly on all camerists, that while with expensive accessories and a large studio one can most easily do fine work, it is possible in a smaller room, with considerable exercise, it may be, of brain and body, to bring about results of which one need not necessarily feel ashamed.

Of course a good lens and plates are absolutely necessary. Mine was a Voigtlander W. A. Euryscope, and I used for two of my negatives Newcomb and Owen’s plates, and for the other Allen and Rowell’s. Both were sent me especially for this purpose and were equally good. A quick inventive brain can supply more of the other requisites than would be believed possible by those who think that such things can always be purchased. But it means hard labor every time and a willingness to put one’s own hands to every detail of the work. With every obstacle or troublesome difficulty I was continually told it was impossible to do thus or so, to which my reply was, “I don’t like that word, very few things are really impossible.” “Well, I don’t see how you are going to manage,” would be the comment on this, to which I would say: “Neither do I, at this moment, but I mean to find a way.” The portrait studio is an excellent place for patience to have her perfect work, and the Christian graces find plenty of unconscious teachers through which to impress themselves on many a pupil. But it is a curious fact that the more one does the more one can do, as long as strength lasts, and if women could always systematize their work as men can the results would startle them.

The manifold cares of a household with its incidental “werryments” make regular work of any kind difficult, if not impossible for many of them, but determination works wonders, and I wish to urge on all, women and men who find in camera work a vital source of interest and benefit, do not play with the work, but make it a real, genuine part of yourself and you will be doubly, trebly rewarded. In its far-reaching, ever-extending field of exploration you will gain a broader, wider, deeper culture than you dreamed might be possible, and deeply as I revere and honor the work of brush and palette I shall never regret my transferred allegiance to the camera. (pp. 347-50)