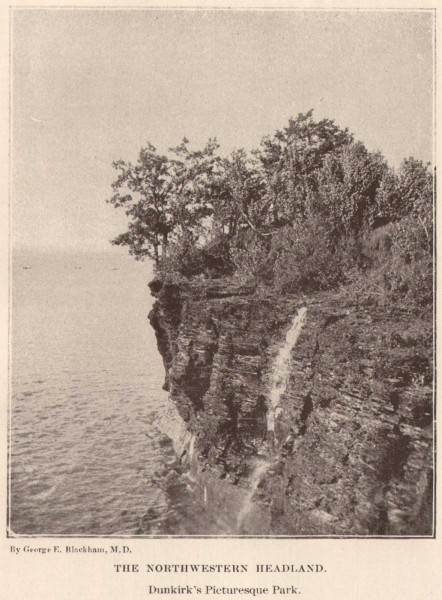

The Northwestern Headland | Dunkirk's Picturesque Park

PhotographerGeorge E. Blackham, M.D.

CountryUnited States

MediumHalftone

JournalThe American Amateur Photographer 1892

AtelierNone Listed

Year1892

View Additional Information & Tags

Geology, Landscape, Lake, Marine

Dimensions

Image Dimensions: 10.8 x 8.7 cm October

Support Dimensions: 23.0 x 15.3 cm

An article espousing the virtues of snap-shot photography done locally by Blackham is included with several illustrations including the frontis for the October issue:

Dunkirk’s Picturesque Park.

By George E. Blackham, M. D.

“WHEN I read in the photographic journals accounts of trips with the camera through various picturesque regions and see the beautiful views brought back by the favored ones who are privileged to take such trips, I am, at times, almost persuaded to break the tenth commandment and covet my neighbor’s leisure, for I am a busy man, to whom a holiday is a rarity, whose photography must be done, like Prince Hal’s repentance, “at odd times as I have leisure,” and whose excursions with the camera must, as a rule, be confined within the limits of an afternoon’s drive. This condition of affairs has one compensating effect—it makes one seek and find the beautiful in one’s immediate surroundings, which might be overlooked if one were at liberty to seek more distant scenes in search of the picturesque.

The city of Dunkirk, N. Y., was originally laid out by a syndicate of capitalists, who expected it to be a great metropolis. It is beautifully situated on a nearly semicircular bay, whose curving shore-line terminates, on the east and on the west, in two bold headlands, whose rocky bluffs rise, almost perpendicularly, some thirty feet above the waves which lap their feet. The western headland is known as “Point Gratiot,” and bears upon its extreme end a fine lighthouse, belonging to the United States, and equipped with a large Fresnel lantern of the second class. On this headland is a reservation of about fifty acres, set apart by the syndicate, and donated to the municipality of Dunkirk, in perpetuity, for a public park or pleasure ground. The deed of gift is hampered with some restrictions, which virtually forbid the improvement of this park, so that it remains today, with the exception of a roadway or drive around its margin, almost as wild as in the time when “the woods were full of catamounts and Indians red as deer,” and it is to this one bit of nature, undefiled by art, that I often resort for snaps and time exposures. And it is wonderful how inexhaustible a variety of views can be found in this little fifty-acre lot: how every change of season, and even of time of day, reveals new beauties.

In starting for “the Point,” I generally walk directly down to the shore, and thence westerly along the sandy beach. The view from this point is fine, though marred by an ugly row of piles erected as an artificial defense against the encroachment of the lake, which, urged thereto by what the late Mr. Longfellow poetically described as “The Northwest wind Kewaydin,” has been trespassing upon the shore-line till Front street has here become Water street.

From this beach we obtain a view of the Point and lighthouse, with the breakers rolling in after a storm. Coming closer, we get a better view of the lighthouse and keeper’s residence as seen from the southwest. The buildings are substantially and even handsomely constructed of cut stone. Another striking feature is the northwestern extremity of the Point, as seen in the frontispiece, which displays the peculiar laminated structure of the clay slate of which the bulk of the headland is composed.

The winding driveway known as the West Path is a very lovely drive as it winds in and out through the forest, occasionally approaching so near the edge of the bluff, with which it runs approximately parallel, thai glimpses of the lake can be seen here and there through the boughs, and again turning more deeply into the heart of the woods. This picture is the only “time exposure;” all the other illustrations are “snap shots.”

The view where the South Drive turns northward to become the West Drive is a shutter exposure, and though it lacks the detail of the West Drive picture, it gains an element of human interest in the figures, whose movement would have spoiled a time exposure.

There are many rocky nooks on the west shore of the Point. The waves roll in and dash themselves into spray against the perpendicular face of the cliff, and, as the lake is very wide, the opposite shore being below the horizon, there is something of the grandeur of an ocean that attracts one.

In the view of the long beach at the southern end of the park the shore slopes gradually up from the water’s edge and is covered with that mixture of fine white sand-rounded stones of all sizes that, I believe, our British friends know as “shingle.” This beach affords safe and delightful bathing—not yet appreciated as it will be in the near future, when our citizens awake to the full beauty and value of their free pleasure ground.

So we have taken a Summer afternoon’s ramble around Point Gratiot, or, as it is better known in Dunkirk, “the Point;” it is for us the Point par excellence.

In Winter, when the ice is piled in picturesque heaps along the shore, and the frozen surface of the lake stretches out in arctic whiteness to meet the dull-gray sky, it presents a new and entirely different set of attractions to the photographer; and even in Summer there are tempting groups of picnickers with their hammocks swinging between the trees, and sometimes, not always, occupied by lonely novel readers, their horses tethered to saplings and their lunches spread upon the grass in the shade of the old, old trees that have looked down upon Indians, wigwams and campfires.

But while one might easily gather illustrations for every chapter of a novel, even the hand-camera fiend has, sometimes, a conscience, and I feel that I have no right to spread these scenes from little private dramas before a curious but not always sympathetic public. It is enough if I have succeeded in showing that the amateur photographer need not always go far afield for subjects of beauty as well as of interest, and that the “snap shot” has its legitimate place beside the time exposure in the field of picturesque photography, and that to catch the foamy crest of the breaker as it flies is as truly artistic as to bring out every detail of leaf and twig, of light and shade, with a slow plate, small stop and long exposure.

Note.—The pictures illustrating this article were taken with a Gundlach 4x5 rapid rectigraphic lens in a Hawkeye camera on Eagle orthochromatic plates, and developed with eikonogen and hydroquinone. (pp. 431-34)