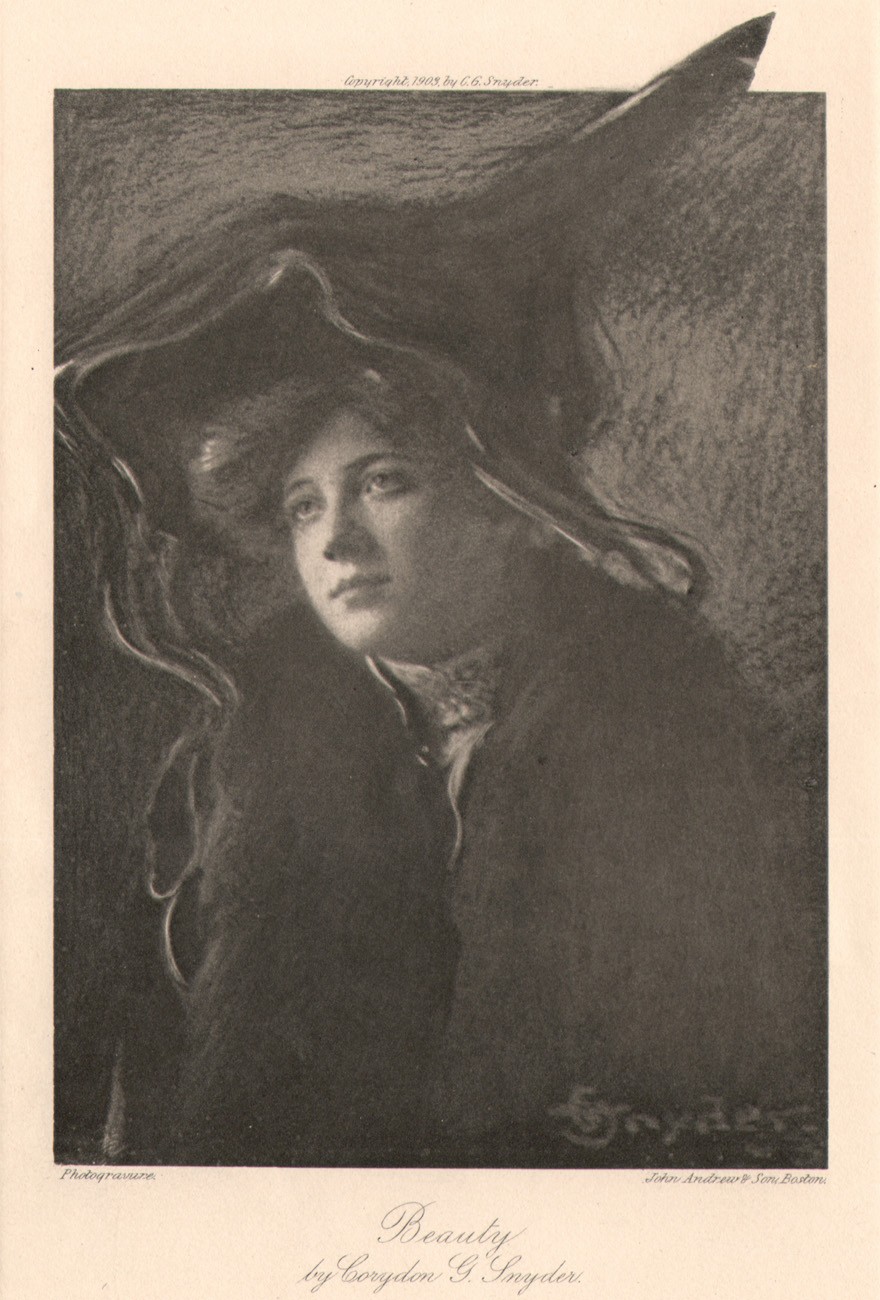

Beauty

In the early 20th century, the American portrait photographer and (later) magazine illustrator (1.) Corydon G. Snyder (1879-1968) developed a specialty of combining drawing and portrait photography to produce what he loosely called the Photo-Sketch, with a variation on the process called a Photo-Etching. Collectively, he called them Corydon Etchings. As outlined in an article he authored which we reproduce later here, Snyder gained the insight for these processes after he learned of the potential of altering halftone cuts while apprenticing in a photo-engraving establishment beginning in 1897. In researching background on Snyder, I have observed examples of his “sketches” displaying a heavy amount of hand-work: they mostly resemble drawings but with the face of the subject typically left untouched. Conversely, this example of a Photo-Etching displays more of the handwork in the background, with the elaborate hat worn by the subject altered and amusingly, extended outside the confines of the rectangular part of the image and into the border area within the plate marks.

In 1906, two years after this photogravure appeared in The Photographic Times-Bulletin, Snyder, now affiliated with the Metropolitan Camera Club of New York City, posted an advertisement for his Corydon “Photo Sketch” Book in the March issue of The Photographic Times:

The Corydon “Photo Sketch” Book: A complete text book on this beautiful art, written by Corydon G. Snyder, will be ready soon, containing full illustrated directions for making the famous styles. A book for professional and amateur.

Write at once for big free offer

Corydon G. Snyder

Metropolitan Camera Club

102 W. 101st street, New York City

A dozen years later, there was a revival of sorts with his processes, and he wrote an extensive article on its’ background for the December, 1914 issue of San Francisco’s Camera Craft:

Some History of the Photo-Sketch

By Corydon G. Snyder

Owing to the fact that there are so many who claim to have originated the Photo-Sketch and Etched-Negative processes, I think it best, before proceeding with other articles on these subjects, to tell what I know about their origin and my own connection therewith. Since again taking up the work of instructing in this branch, I quite often run across the trail of a new claimant. As but little has been published on these processes, each of these undoubtedly has good grounds for at least claiming to have originated the particular process he employs, even if it be similar in detail to that used by some one else.

Ever since the process of halftone engraving was discovered there have been done more or less vignetting and other hand-work improvement of the photographic print before the printing plate is made therefrom. Such work was being done when I started, as an apprentice, in the art room of a photoengraving establishment. This was in 1897, and I did my share of this hand work on photographs of both mechanical and artistic subjects. This working up of the picture is usually done by air-brush in combination with hand-brush work. The problem for the artist, aside from the skill usually possessed, is comparatively simple, as the engraver can follow any effect in finishing the halftone plate.

I had been employed at this work but a short time when I purchased my first camera, a 4×5 instrument using plates. My first photographs, not being especially good, I essayed doctoring them up, working on the prints after the manner employed on copy for the engraver. A number of my friends were theatrical people, and they made very good subjects for this kind of work. The effects I obtained were well liked and a number were used as originals or “copy” for cuts for publicity and advertising purposes. I later purchased a 5×7 camera and continued doing some professional portraiture, mostly in connection with my art work. I early experimented to find a method of getting the desired effects on the negative instead of working on individual prints, so that I could make duplicates without so much trouble. Up to this time I had never seen any prints made from negatives that had been etched or otherwise manipulated to get the sketch effect. My experiments were varied; I tried all manner of effects and various methods of obtaining them. The etching and the sketch required different methods to give the different effects, so I classified them and called the pencil and wash drawing effect the “Photo-Sketch,” and the etching effect the “Photo-Etching.” This last name being rather likely to be confused with the photoengraving process, I called my own work along this line “Corydon Etchings.”

I also did some work that I called “Corydon Film Etchings.” These were made by exposing a film to light sufficient to obtain the required density, developing it, and then doing my etching thereon. This film carried no photographic image, but after being hand etched was used with the same intent that a drypoint etcher uses the copper plate; only, instead of using ink and press as he does, the etched film is printed in the same way a negative is. As far as I know, I was the first to do any of this work; and, aside from that done by students of the “School of Corydon Etching,” started in 1904, I have never seen any others.

To etch the film of one of these evenly darkened plates direct from the model would be quite difficult on account of the necessity of working at a retouching stand. Therefore, it is best to first make an ink or pencil sketch and then use it as a guide in making the etching. Another plan is to make a rather flat copy negative of your sketch and work over that. These of course are methods that overlap the Photo-Etching process, as one is really working on a negative despite the fact that there is no photographic image.

The first of my etchings that were reproduced in print appeared in The National Magazine in 1902, and I had an article illustrated with some of my etchings in the Broadway Magazine of January, 1903. I submitted a number of these etchings and one “straight” photograph to the First American Salon of 1904. The jury refused to consider the etchings, but the straight photograph was accepted. Previous to this I had exhibited in the Chicago and Minneapolis Salons, but did not again try the National. Much of the artistic photography that is accepted is more or less faked, and I believe that any work which tends to produce an artistic picture should be considered as allowable. Those in which the hand work is so very apparent, as in the case of the etching and sketch process, could be set apart. I believe that this movement will grow amongst the artistic photographers having an inclination toward drawing.

The ordinary photographer may not be able to do much original work, but he can at least add a few of the simplest of these effects to his line; and these, pushed with good judgment, should tend to increase his reputation as well as his bank account. The first prints I ever saw made by another, showing that hand work had been used in connection with the photographic image, were made by a photographer in the Dearborn Theater Building, Chicago, in 1902. I have forgotten the photographer’s name, for which I am sorry, as I would like to give him credit here. While I had, at that time, already perfected my methods, I had done so little professional work that there was not much chance of his having gotten the idea from seeing samples of my work.

The first published work that I saw, came, some time afterward, from the Strauss Studio, St. Louis, and I should say that they were Photo-Sketches. Understand me, I do not say that either of these gentlemen, or whoever did the work for them, had not done this style of work before these dates; or, for that matter, before I did.

When I first came to Minneapolis in 1903, Sweet Brothers were showing some samples along the style of the Photo-Sketch. I have been told that an artist by the name of Graves did the hand work. I called on one of the proprietors and showed him samples of my work and he was surprised to learn that any one had carried the processes so far. He stated that they had tried to get a patent on the process, believing themselves to be the originators.

In 1904, another artist named Clay Kelly, and myself, organized a correspondence school to teach Photo-Etching and Photo-Sketch methods. As it seemed to require more application to learn the etching than the average photographer had time to give, few of the students went far with that process, but the Photo-Sketch gave them little difficulty. Owing to our methods of teaching, employing original prints and personal correspondence, the cost to us in time and trouble left no profit in the amount received for the course, fifty dollars, so we closed the school to new students, gave those who had enrolled a chance to finish, and destroyed the plates. For a few years following I did theatrical work exclusively, using both the sketch and etching methods. While doing this in New York in 1905, several others were showing like work in their cases. While commercial illustrating has of late been my main line, I have continued to do some of this work for old customers or in connection with my art work. However, I have received so many requests for instructions since the school was discontinued that I have gotten out instruction sheets showing how the work is done; for, while the idea is simple enough, there are some technical details that one should know in order to avoid useless experimenting. I hope, in the articles to follow, to be of help to those who are doing this work as well as to those who wish to take it up. (2.)

It seems the purpose of this lengthy article was also a marketing opportunity for Snyder and that is why he had applied for copyright protection in 1914 for a small booklet priced at $1.00 that he called The Photo-Sketch. The work, advertised in the pages of The Photo-Miniature in 1915, was available directly for purchase by contacting him at his Minneapolis, Minnesota address, listed at the time as 3248 48th Ave. So. Conveniently for Snyder, some type of arrangement was made with the editors of the Photo-Miniature, who apparently thought enough of his combination sketching and photography process to comment at length in their July issue:

I have often wondered why the Photo-Sketch is not more popular among professional and amateur photographers. It has all the attractiveness of the everyday portrait, without its heaviness and over-abundant detail. It offers the photographer a splendid field for the exercise of his individuality, and, as a distinct style in portraiture, it is bound to make a strong appeal to the sitter. What is a Photo-Sketch? It is the usual photographic portrait as far as the head, face and hands are concerned, but with handwork, or more properly, pencil work, taking the place of the usual photographic delineation of clothing and accessories. This pencil work adds lightness and grace to the portrait, giving it, in fact, the peculiar attractiveness of a sketch portrait. An example of the Photo-Sketch may be seen in the announcement of Mr. Corydon G. Snyder, among the advertising pages of this issue. Mr. Snyder has devoted some years to the perfection of his work along this line, and now offers instructions as to the making of this style of portraiture for the modest sum of one dollar. The work is not at all difficult, and readers who are interested in portraiture can hardly spend a dollar to better advantage than in getting the method from Mr. Snyder. (3.)

1. It cannot be substantiated here through source material at this time, but an online post states Snyder provided illustrations for women’s magazines during the Art-Deco era including The Delineator, Vogue and Home & Garden, among others.

2. Some History of the Photo-Sketch: By Corydon G. Snyder: in: Camera Craft: Fayette J. Clute, editor: San Francisco: Vol. XXI: December, 1914: pp. 581-584

3. Notes and Comment: in: The Photo-Miniature: Tennant and Ward: New York: July, 1915: p. 349