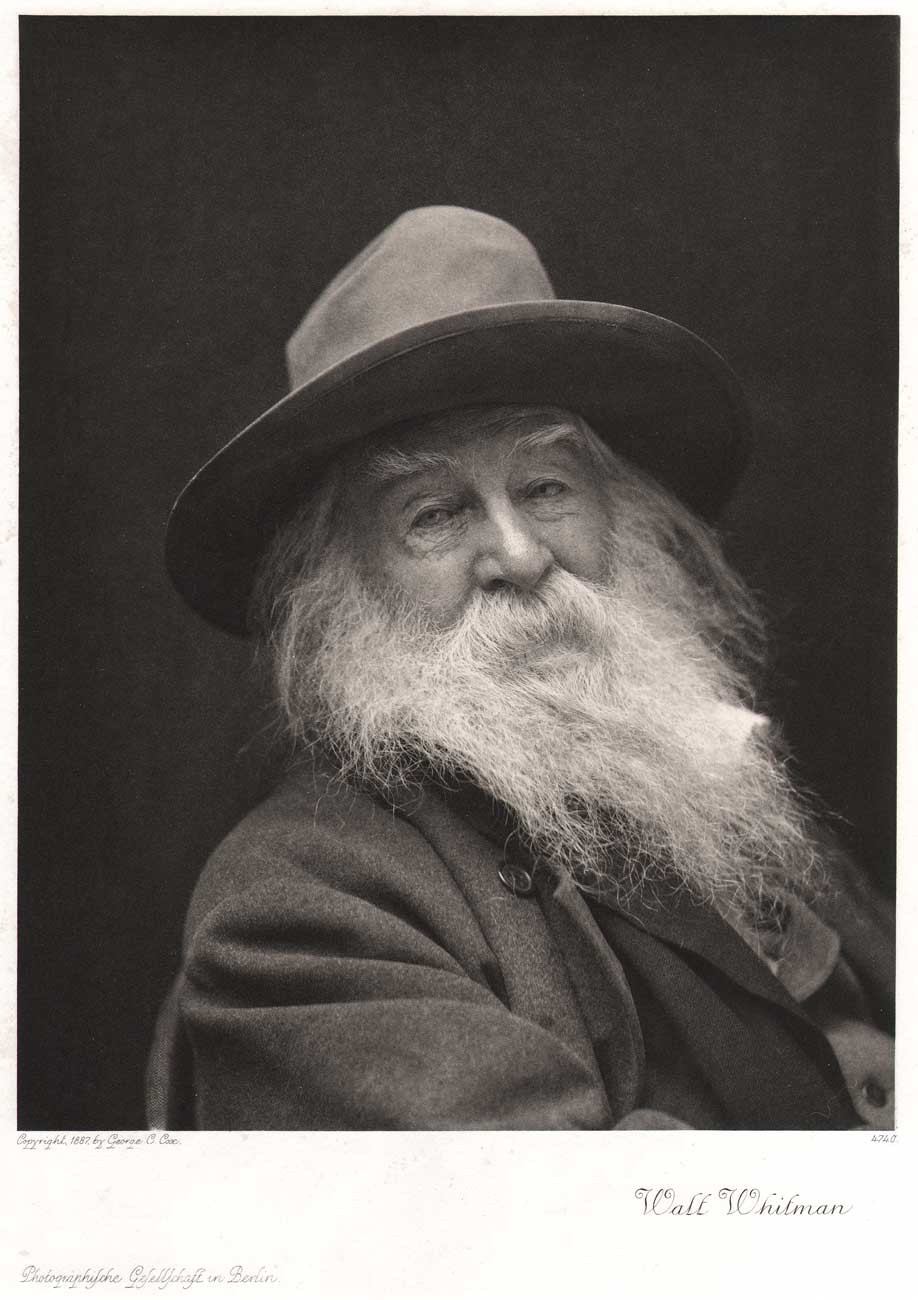

Walt Whitman: The Laughing Philosopher

“But it is his soul! How can one photograph a soul?”

This famous photograph by poet Walt Whitman (1819-1892) was taken in 1887 by American photographer George Collins Cox (1851-1902) in New York City. A fascinating profile of Cox and his working methods illustrated by a series of his portraits by Ida M. Tarbell appeared in the May, 1897 issue of McClure’s Magazine:

A Great Photographer

PHOTOGRAPHY is treated so generally as an art in which a machine does all the work, that it is difficult to believe that some of the greatest portraits of our time have been produced by this medium. It is true, however, that the ideal requirement of a portrait—to give a glimpse of a man’s soul—has never been more nearly satisfied than by a few photographs made several years ago in England by Mrs. Julia Cameron, and by a large number made in the last few years in New York by Mr. G. C. Cox. Of Mrs. Cameron’s work this magazine has already given its readers some specimens.*(Dec. 1893-editor) The present article is devoted to that of Mr. Cox.

So quietly has Mr. Cox’s work been done that, except to a limited public particularly interested in purely artistic results, it is unfamiliar. He has never sought general recognition. Conscious that what he was. striving to attain would be understood by only a few men, he has worked for them alone, seeking their criticisms and suggestions and observing closely the effect on them of what he had done.

To appreciate his method of work, one should have a sitting in his studio. The experience is altogether unusual. One does nothing as in the conventional studio. He is not posed. He is not bidden to look at the ” upper right-hand corner” of anything. He is not asked to smile. He is not made to keep quiet while a watch ticks out an interminable minute. As for the camera, it seems hardly to come into the operation. Probably many persons have had a series of portraits taken by Mr. Cox who afterwards were unable to tell without an effort where the camera stood and how it was operated. All this is natural enough if one understands what the artist is trying to do. His treatment of a sitter is founded on his theory that all men purposely or unwittingly wear a mask, and that unless this mask can be torn away and the emotions allowed to chase freely across the face, no characteristic picture is possible. His first effort then is to get rid of the non-committal mask; to make the subject forget himself, the camera, his mission at the studio.

An ordinary man could not do this, but Mr. Cox is no ordinary man. He is original, sincere, witty, and in profound earnest over his work. The subject who comes to him prepared to pose is surprised to be greeted with what seems to be quite irrelevant, though decidedly brilliant, talk. Mr. Cox has known many of the most interesting people of the last twenty years, and has a great fund of unusual anecdotes about them. When he begins to tell stories of Whitman and Beecher, of William Hunt and Richardson, of Amélie Rives and Duse, it is only an unusually dull and preoccupied mood which will prevent one from becoming interested. The quaint and original expressions; the unconventional opinions; the odd personal observations; the contempt for shams, surprise and arouse the subject. Before he is aware he, too, is talking animatedly. Mr. Cox tells with appreciation how Bishop Taylor, the great African missionary, came to him once to be photographed. He was for some time indifferent and dull, not understanding at all what the artist was after, but finally thawed out, and Mr. Cox caught one of his best portraits just as the aged Bishop finished telling with great gusto the story of a young man coming to the ship to see him off on a recent voyage.

“Good-by, dear Bishop,” he blubbered; “I shall probably never see you again.””No,” said the Bishop, “you may be dead when I get back.”

It is not only the habitual mask of a face which must be conquered. Many people suffer from what is called “camera fear.” In front of the machine they become, in spite of themselves, rigid and lifeless. Cox believes that this peculiar feeling is best conquered by taking the subject in his own home or place of work. There he naturally wears a lighter mask and falls more readily into characteristic attitudes. Many of Mr. Cox’s happiest results have been obtained by studying his subjects in their own homes. Thus the fine portrait of Richardson was taken in the architect’s house. His recent experiences in photographing Mr. Cleveland at the White House and Major McKinley at Canton, have been equally convincing that if one wishes to make a real portrait it is wiser to study the subject where he is most at home.

In taking photographs Mr. Cox aims to make as many as six negatives. A complete series of his pictures runs the gamut of a man’s soul from the moment of smiling ease to the one of anguish. Not that he always succeeds in completing the series; he rarely fails, however, to get several characteristic pictures. What could be more characteristic, fuller of sweetness and truth than his portrait of Whitman? He has given us in it what must remain the typical portrait of Whitman—a portrait which is the foundation of Johnson’s great etching, which George Barnard, the sculptor, declares has been his inspiration, and at the sight of which Duse cried out, when it was shown to her, “But it is his soul! How can one photograph a soul?”

It is not to be supposed that all of Cox’s sitters yield themselves unresistingly to his unusual procedure. Trained to pose to a camera, many are inclined to resent the artist’s effort to interest them and make them forget the object of their visit. There are others who insist that, unless a face is lighted in a certain way, the result cannot be satisfactory—slaves of a theory, they fail to see that this is a revolutionist regardless of conventions, whose only aim is to get the fine thing he sees.

Another difficulty with which Mr. Cox struggles is the almost universal notion that a portrait should be something decorative. Many a woman who goes to him makes a really characteristic picture impossible by her elaborate preparations. Nothing could be more fatal to the Cox idea. Chiffons are as inappropriate in one of his portraits as trefoils on a Grecian facade. Where a woman dresses especially for her picture all that Cox can get is, as he says, ” a picture of her consciousness of her clothes.”

Where the decorative is entirely eschewed, it follows that the subject must have individuality for the picture to be of value. Cox rejoices in the decided character, and shrinks with dismay from a neutral one; there is nothing for him to get hold of. The people who have sat to him have been a rare lot; in the past twenty years he has photographed Walt Whitman, Richardson, General Sherman, C. A. Dana, Melchers, Howells, Hunt, Beecher, E. E. Hale, Duse, and hosts of others. In most of the cases the portraits he has made will remain the standard ones of their several subjects.

The Cox portrait, however, appeals primarily to the discerning mind and the artist’s eye. Ordinarily it clashes too hard with the conventional idea of a photograph. The unusual is to many the unmeaning. It is this fact that comes in frequently to depress and discourage the artist. Often he hesitates to seize with his camera what he sees in a face, because conscious that it will not be understood. He shrinks from putting before subjects something which means a great deal to him but will mean nothing to them. The real reward in his work lies in his ability to produce that which is an inspiration to those who, like himself, are seeking independently to do sincere, truthful work, rich in a value of its own. (1.)

A first-hand account of the Whitman sitting which produced The Laughing Philosopher portrait appears at the Walt Whitman Archive website:

“On the morning of April 15th, 1887, George Cox took several photographs of Whitman, who was celebrating the success of his New York lecture on Lincoln, delivered the day before. Whitman recalls that “six or seven” photos were made during the session, but Whitman’s friend Jeannette Gilder, an observer of the session, said there were many more than that: ‘He must have had twenty pictures taken, yet he never posed for a moment. He simply sat in the big revolving chair and swung himself to the right or to the left, as Mr. Cox directed, or took his hat off or put it on again, his expression and attitude remaining so natural that no one would have supposed he was sitting for a photograph.” (2.)

The Photographische Gesellschaft in Berlin

Often confused by the literal English translation as “Photographic Society”, the proper name for the Photographische Gesellschaft in Berlin is actually The Berlin Photographic Company. Established in 1862 in Berlin, Germany with retail and distribution branch offices located in New York, London and Paris, this large art publishing house was founded by the brothers Christian “Albert” Eduard Werckmeister, (1827-1873) an engineer and chemist, and “Friedrich” Gustav Werckmeister, (1839-1894) a painter and etcher. The concern was collectively owned and run by their younger brother Emil Werckmeister. (1844-1923) The majority of this firms efforts was concerned with the reproduction and sale of engravings and notable oil paintings by master artists in the collections of major museums and collections throughout Europe. The permanent process of photogravure was a specialty of the house and around the turn of the 20th century, a collection of portraits of notable men and women of mark from a myriad of disciplines were offered for sale, simply listed as “Portraits” in the company’s 1905 New York general catalogue. (3.)

Corpus Imaginum

By 1907, an advertisement in the Berlin catalogue of the Photographische Gesellschaft for the collective body of these portraits appeared as Corpus Imaginum, (4.) Latin for “Body Likeness” . They were described as “Authentische Bildnisse aus Vergangeheil und Gegenwart” –Authentic Portraits of Past and Present– with the folio sized, photogravure plates (45 x 33 cm) printed on Dutch handmade deckled edge plate paper and selling for 2,50 Marks in Germany and $1.50 in the U.S. The 1905 American catalogue gives a further description of the plates, the majority of which were done from original paintings:

All reproductions of the Berlin Photographic Co. (save a few taken from drawings, indicated in the catalogue by the lettter “a” behind the number) are taken directly from the originals, and printed and published in our Studio, at Westend, near Berlin, Germany. Neither energy nor expense were spared to make our collection a truly representative one.” (5.)

By 1910, this “Corpus” had grown to over 500 portraits as stated in the New York catalogue. These as well as the Cox photograph of Whitman, (one of a few select portraits done “from life” by the company- reproduced as a small halftone in the “Portrait” section of the New York catalogue), were actively marketed to schools and libraries, who often purchased them to be used as wall decorations in classrooms and reference print collections by library patrons. A 1912 notice in a library trade journal described the Corpus Imaginum as:

Authentic Portraits of the Past and Present is a list of about 500 excellent portraits in photogravure after photographs from life or authentic paintings of artists, scientists, musicians, historians, men of letters, etc. Small for wall pictures. Size, 13″ x 18″, single plates, $1.50. (6.)

By 1916, with World War I in full swing, the London and New York branches of the Berlin Photographic Company were closed under the Trading with the Enemy Amendment Act by resolution of the British government. (7.) With the business impacted by the war and Emil Werckmeister’s death in 1923, the Photographische Gesellschaft company most likely closed around this time, although facts regarding specifics are unknown at the present by this author.

The Corpus Imaginum copper plates, numbering over 900, are now owned by the Blanc Kunstverlag in Munich, succesor to the Franz Hanfstaengl Kunstverlag, with this atelier carrying on the art of fine gravure printing by hand. The firm has continued this tradition with modern reproductions from the original Corpus Imaginum plates since 1980.

Notes:

1. A Great Photographer: Ida M. Tarbell: McClure’s Magazine: New York: May, 1897: pp. 559-564. The article is illustrated by a series of halftone portraits including: Donald G. Mitchell, an unknown photograph of woman playing a violin, Walt Whitman, (plate originally published as photogravure in “Sun & Shade“: variant of the Laughing Philosopher) Eleonora Duse, Bishop (William) Taylor, Walter Shirlaw, and Henry Ward Beecher. This article further reprinted in the July, 1897 issue of The Photographic Times.

2. excerpt: Walt Whitman Archive online resource accessed July, 2014

3. Approximately 130 portraits are individually listed in the 1905 Berlin Photographic Company catalogue printed in New York City.

4. The successors to the Franz Hanfstaengl Kunstverlag in Munich, the Blanc Kunstverlag, states on their website that “Around 1850 Franz Hanfstaengl began the Corpus Imaginum Collection which even today includes portraits of over 900 well-known personalities.”

5. excerpt: Preface: Catalogue of the Berlin Photographic Company, Fine Art Publishers: New York: 14 East 23rd St. :1905. The Berlin showroom for the Photographische Gesellschaft was located at 1, Stechbahn, with additional showrooms in Paris; (10, Rue Vivienne (Societe Photographique) and London at 133 New Bond Street. Approximately 130 portraits are listed in the 1905 catalogue described as being printed from 9×7″ plates on Dutch handmade paper. By 1910, the Berlin Photographic Company catalogue states over 500 subjects made up the complete portrait catalog of the company along with a new address for the New York showroom moved to 305 Madison Ave. near 42nd Street.

6. John Cotton Dana: Modern American Library Economy as Illustrated by the Newark, N. J. Free Public Library: Part VI: Art Department: The Elm Tree Press, Woodstock, Vermont: 1912: Modern Library Economy: 76-636

7. notice: American Art News: New York: July 15, 1916. (from The London Gazette)