La Photographie Est-Elle Un Art?

Original copy for this entry posted to Facebook on January 4, 2012:

I’ve just posted a small collection of gravures in the form of a small folio titled La Photographie Est-Elle Un Art? (Is Photography an Art?) on the site. the work was originally published in the form of a treatise defending pictorial photography in 1897 by the French art historian, critic and author Robert de La Sizeranne. (1866-1932) I’ve included some background on Sizeranne- notably an essay translated several months later by the American Monthly Review of Reviews in 1898 noting modern successors to old-fashioned photographers had no use for “cardboard rocks” in their photographic backdrops.

Introduction

La Photographie Est-Elle Un Art? (Is Photography an Art?) was first published as a treatise arguing the advocation of pictorial Photography as a recognized art form by the French art historian, critic and author Robert de La Sizeranne (1866-1932) in the December, 1897 issue of the Paris journal Revue des Deux Mondes. 1. The work however was not illustrated, and criticism of Sizeranne’s writing on the subject was apparently severe enough for him to have it re-issued along with examples of hand-pulled photogravures and numerous halftone plates in a volume by the Paris publisher Hachette & Cie in 1899 under the same title.

Criticism, and Response

The Photogram of London provides some context:

“Is Photography an Art?—This is the question put by M. de la Sizeranne in the December issue of the Revue des Deux Mondes. After discussing the pros, and cons., the author answers in the affirmative. M. de la Sizeranne quotes the works of British camerists very largely and thinks that the “art” is only in its infancy. The article has been much criticised, so that to support his contention we learn privately that M. de la Sizeranne will shortly bring out an album de luxe containing examples of the best recent work, in which this country will be strongly represented.”2.

Background: Robert de La Sizeranne

Robert Henri Marie Bénigne de La Sizeranne was educated at the College de Vaugirard in Paris before eventually studying law. He was admitted to the bar in 1895. (3.) His older brother, Maurice de la Sizeranne, (born 1857) became blind at the age of nine, around the same time (1866) Robert was born. Maurice eventually was made a Chevalier of the French Legion of Honor and founded La Revue Braille in 1883. (4.) Although more scholarship would be required, one cannot underestimate the effects of Maurice’s handicap on Robert and his subsequent interest in art criticism. After first authoring his first known volume in 1887, a booklet defending the international constructed language known as Volapük, (5.) Robert de La Sizeranne would eventually become a very prolific author, concentrating on the history of English painting of the nineteenth century; the Italian Renaissance; the aesthetics of John Ruskin, (see: Ruskin et la Religion de la Beauté : Paris: 1897) as well as photographic aesthetics. 6.

Photographers & Artists

Photography became a critical area of investigation and defense by Sizeranne in the early 1890’s, almost certainly influenced by exhibitions of photographic art by members of the Photo Club de-Paris. Before his refined treatise first appeared in 1897, he authored an article four years earlier titled The Photographer And the Artist (Le Photographe et L’Artiste) in the same publication La Photographie Est-Elle Un Art? was published. (7.) In reviewing this article, it is keen to note Sizeranne had already become an exponent of photographic art, and he makes a vigorous case it should stand on its’ own as well as something to be embraced by painters. In making his case, he draws back as far as Greek art, with a comparison of horses in motion as depicted as frieze sculptures at the Parthenon to those of scientific photographic studies made by Edward Muybridge, among other examples. The journal The Chautaquan translated Sizeranne’s article in full. The following excerpt begins the four page article:

“THERE is at Chalon-sur-Sâone a statue of Niepce which represents the celebrated inventor in a standing position and pointing his finger as if at some menacing object, with the air of a cannoneer who defies any approach. One feels an impulse to seek out what invisible enemy it is which thus from a distance threatens the photographer. It seems in these times as if it might well be supposed to be the artist, that man of interpretation, of fancy, and of dreams, springing out from that indefinable, intangible world of sentiment, in which he finds his home, his passion, and his joy.

In fact photography, rightfully proud of its late developments, and justly confident of the still further progress which in the near future will double its domain, no longer limits itself to the utilitarian tasks in which it has excelled. It is not willing to serve now only in the role of tracking criminals and of discovering stars, of magnifying the imprints of counterfeit stamps and of making from the height of balloons marvelous cadastral surveys, of counting the vibrations of insects’ wings and of recording the movements of machinery, or of seizing upon the human face the fleeting indications of a morbid symptom.

It tends not only to become itself a veritable art, but also to teach artists the necessity of understanding in minutest details their own work.” 8.

No More Cardboard Rocks

Two months after Sizeranne’s publication of La Photographie Est-Elle Un Art?, the American Monthly Review of Reviews commented on the work as one of their Leading Articles of the Month in the February, 1898 issue:

“M. de la Sizeranne begins with an amusing description of the astonishment and indignation with which an old-fashioned photographer would regard the goings-on of his modern successors. We have abolished the frosted glass roof, the elaborate arrangement of curtains, the claw-shaped machine for holding the victim’s head in position, the rustic bank, the broken column, the balustrade, the cardboard rocks, the painted cascade, and all the other “properties” which figure so largely in family photographic albums. The photographer, too, is changed. He no longer terrifies squads of children or newly married couples clasping hands convulsively to the great danger of far too tight gloves, with his peremptory order to keep still. The mysterious black shroud in which the old-fashioned operator enveloped both himself and his machine has also disappeared. The modern photographer no longer shuns artists, or condescendingly instructs them in the attitudes really taken up by a man walking or a horse trotting. He mixes with them with the humility of a disciple anxious to profit by the experience of his masters. A visitor to the recent exhibitions of the Photo Club, the Link Ring, the Camera Club, or the Société Belge de Photographie comes out with the feeling that he has been in the presence of an art modest enough, but only half-created, babbling the first words of an unknown tongue. But there are the art critics who prove conclusively, at least to their own satisfaction, that photography could never give results equal to those of etching or charcoal-drawing. How, then, can we solve this problem?” 9.

Continuing, the article mentions:

“Sizeranne quotes copiously from Mrs. Cameron’s Annals of My Glass House”—how, in photographing such men as Thomas Carlyle, she always sought to render not only the external body, but the great mind within, to such an extent that, as she herself says, every photograph taken in that way was almost the personification of a prayer.”

And later adding:

“It is evident that the mind plays an increasing part in the production of artistic photographs. “Why,” asks M. de la Sizeranne, “should we call a man an artist who produces pictures with a bit of charcoal, and deny the title to another who produces pictures by intelligently availing himself of a ray of the sun?” We have no space to follow M. de la Sizeranne through his interesting descriptions of not a few modern photographs, in which imagination, romantic perception, in fact all the qualities understood by the term “fine art,” are discernible. The important point to note is that the photographer is, at least, as much or as little under the dominion of his mechanical apparatus as the etcher or the engraver.”

The article concludes with its’ unsigned author musing:

“M. de la Sizeranne’s conclusion seems to be that photography is yet in its infancy, and that if it is not an art to-day it will be to-morrow.”

Folio Particulars

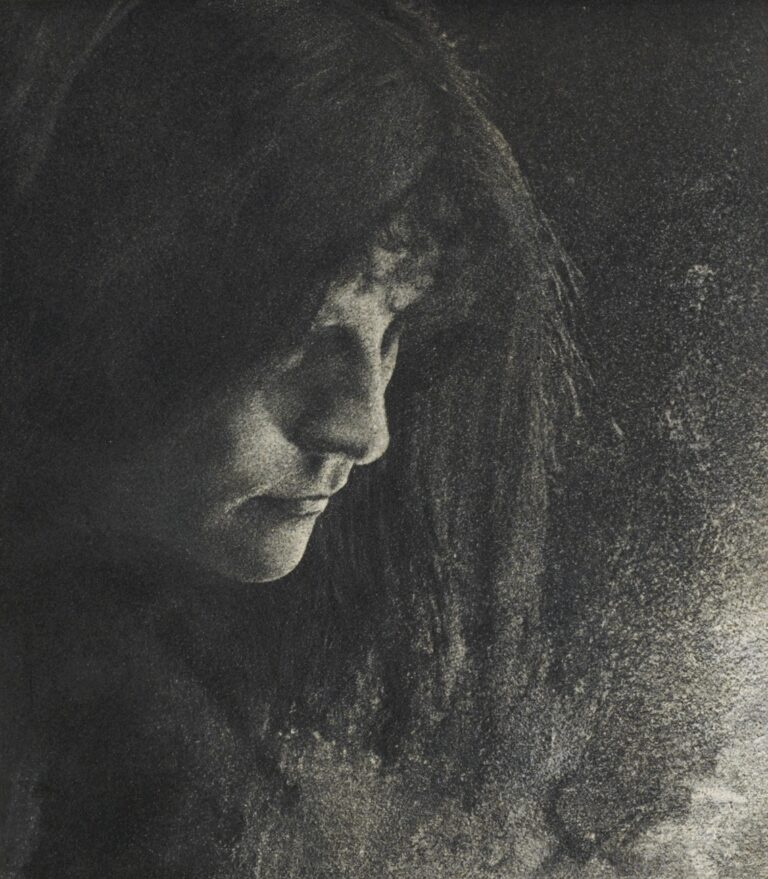

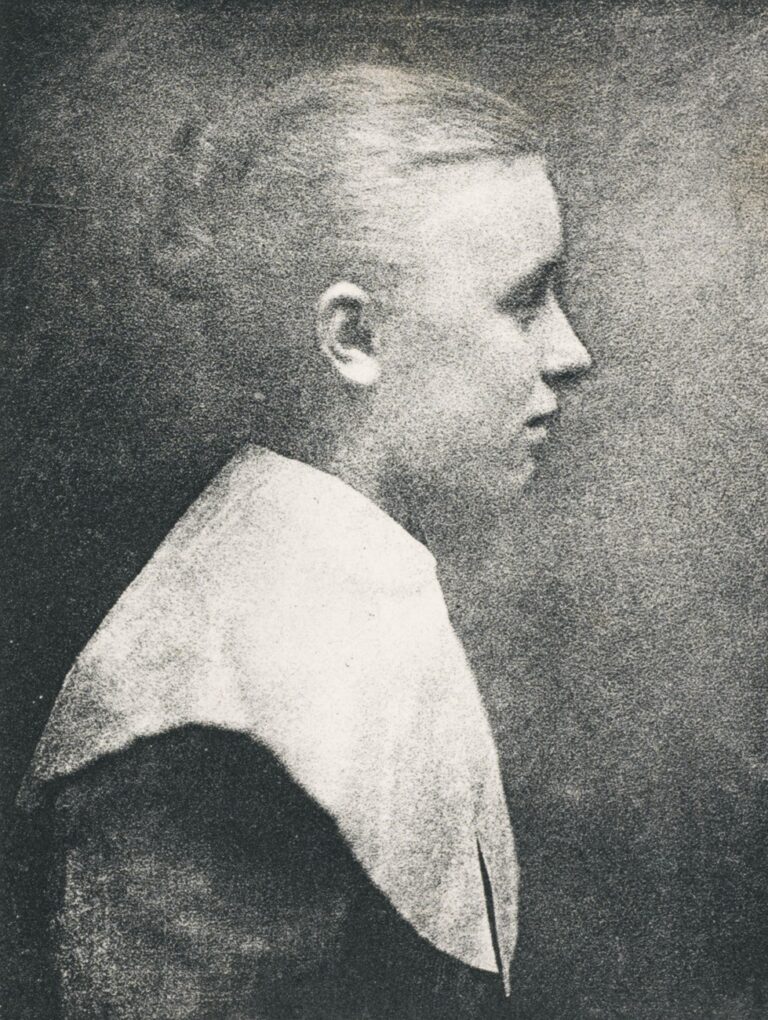

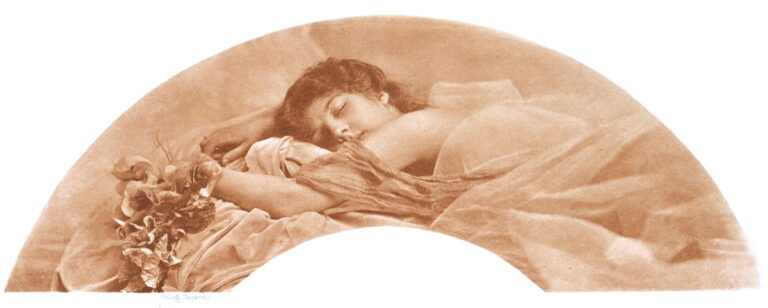

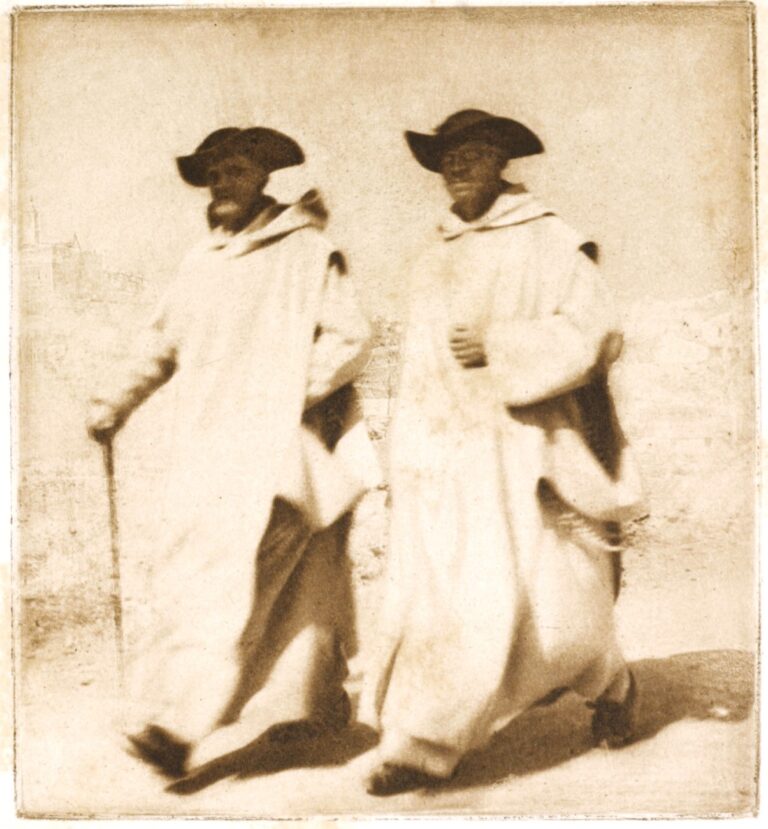

This small folio volume (32.8 x 24.7 cm) was issued by the Paris publisher Hachette et Cie in 1899 with Japanese vellum wraps illustrated with unattributed photogravure vignettes on the recto and verso by French photographer Constant Puyo. The 50 pp. volume is illustrated by seven, hand-pulled photogravure plates protected by tissue guards in addition to 40, in-text halftone photographic plates done by 17 individual photographers. The colophon gives specifics on the illustrations in the book:

Cet Ouvrage Est Illustré

De 40 gravures d’après les compositions de MM Alexandre, Walter Barnett, F. Boissonnas, L. Bovier, M. Brémard, M. Bucquet, D. De Clercq, Craig Annan, R. Demachy, John H. Gear, K. Greger, Henneberg, Horsley Hinton, R. LeBègue, C. Puyo, C. Reid, H. Watzek.

Les 7 planches en taille douce ont été gravées par MM. Craig Annan et Dujardin. Le tirage a été fait par M. Wittmann.

Les clichés typographiques ont été exécutés par MM. Angerere et Golsch, Bertin et Cie, Ducourtioux et Huillard, Fillon, Malvaux et Cie, Mauge, Reymond. Le texte et les gravures ont été imprimés par M. Draeger.

As for the 7 gravures, all stated as being printed by Charles Wittmann of Paris, the atelier plate engraving attribution is not as clear as three carry no credit. It can certainly be deduced James Craig Annan executed his own two plates however: L’Église et Le Monde as well as Les Frères Blancs. The atelier Paul Dujardin of Paris is credited for three: Figure Tragique, Primavera, and Projet d’Éventail by French photographer Robert Demachy as well as the Puyo gravure vignettes for the front and rear covers to the folio. The Heinrich Kühn plate is further identified as being originally from one first made by Blechinger & Leykauf of Vienna but for some reason unattributed in the colophon. The remaining plate by English photographer Alfred Maskell: Jeune Hollandaise– remains a mystery, although it previously appeared three years earlier in a comparably-sized impression executed by the Paris atelier Fillon et Heuse for the deluxe Photo Club de-Paris, Troisième Exposition d’Art Photographique portfolio published in 1896.

Notes

1. La Photographie Est-Elle un Art?: Robert de La Sizeranne:in: Revue des Deux Mondes: François Buloz, Fondateur: Paris: December, 1897: pp. 564-595

2. Current Topics: in: The Photogram: Dawbarn & Ward: London: Vol. V, #51-March, 1898: p. 90

3. Sizeranne biographies: in: The New International Encyclopedia, Volume 13: Dodd, Mead and Company: New York: p. 584

4. Ibid

5. Trois mots sur le Volapük: Paris, H. Le Soudier, 1887 (31 pp.)

6. Online Sizeranne biography: by: Stephen Bann: Institut National d’Histoire de l’Art: Paris: site accessed 2012

7. Le Photographe et L’Artiste: Robert de La Sizeranne: in: Revue des Deux Mondes: Paris: February 15, 1893

8. The Chautauquan: Dr. Theodore L. Flood: Editor: Meadville, PA: Volume XVII: May, 1893: p. 193

9. Leading Articles of the Month: Is Photography An Art?: in: The American Monthly Review of Reviews: Edited by Albert Shaw: New York: February, 1898: pp. 215-216