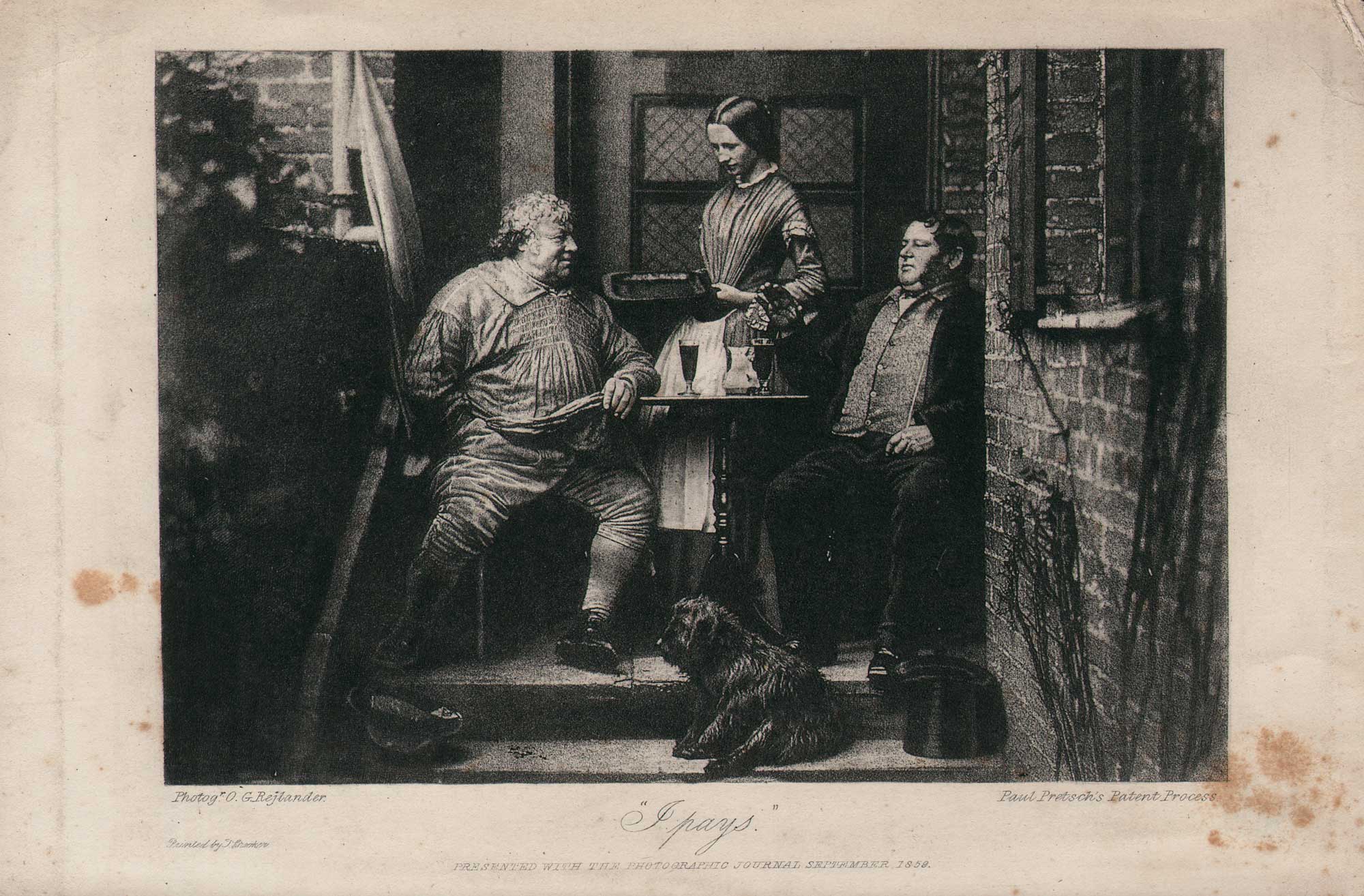

“I Pays”

“The man on the right is executing the privilege of every Englishman, “To grumble, and to pay”: but he is interrupted by the generosity of a man of the people, who is searching in his pocket for some money, crying “I pays”. (Photographic Journal, 15 Sept. 1859) (1.)

Oscar Rejlander: 1813-1875

Swedish painter and genre photographer, settled in England in the 1840s and established a studio in Wolverhampton c.1855. In 1860 he moved to London and worked as a portraitist and genre photographer and died in London, in poverty and debt, in January 1875. He created the photographs for Darwin’s The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals, 1872, posing in five of them. The photographs illustrated various expressions and emotions; that titled “Mental Distress” showing a distressed child, was later exhibited, Rejlander receiving orders for 60,000 prints and 250,000 cartes-de-visite. (2.)

Paul Pretsch: 1808-1873

Austrian photographer and inventor of photo reproduction processes. Pretsch was manager of the Imperial Government Printing Works in Vienna before moving to England in 1854. On November 9th that year, he took out a British patent for the process that he named photogalvanography. The elaborate process required the electroplating of a treated copper plate, the technique taking up to six weeks per plate, and even after requiring a good deal of hand-finishing. However, as Pretsch pointed out, this still compared favourably with the twelve months often required to finish the large steel-engraved plates used to reproduce popular paintings. In 1856, Pretsch issued his first publication – Photographic Art Treasures – containing four prints of photographs by Roger Fenton, at that time the manager of his Photo-Galvano-Graphic Company. The Company was not a financial success and Pretsch had to close down in 1858. In 1863 he returned to Vienna in ill health, and died in 1873. (3)

✻ ✻ ✻ ✻ ✻

On first glance this print of O.G. Rejlander’s I pays looks like an engraving. It appeared as a full page photogalvanograph in The Journal of the Photographic Society of London of 1859 and was accompanied by the article, Photogalvanography, or Nature’s Engraving” authored by Paul Pretsch, the inventor the process. Staging an ‘every day’ moment in the genre style, Rejlander created and captured a narrative imbued with gesture and candid expression, promoting the notion that photographs could be fine art. In this print a frozen photographic moment and an ‘illustrative’ raw ink-on-paper print syntax combine to present to the publication’s subscribers a compelling, well executed and now largely forgotten example of primitive photogravure. One step closer to solving both the permanence and repeatability issues facing photography in the mid 1850s, the print is made from a copper plate electroplated with iron – an early example of aciérage – which enabled a print run of thousands rather than hundreds. A close comparison of the photogalvanograph with an albumen print from the same negative held at the George Eastman House reveals the accuracy of the image’s translation into ink. It also exemplifies the unique look of the ink-on-paper photographic syntax.

From the writing of Pretsch… The photograph as well as the copper plate have not been executed expressly for this purpose and for this journal.; both of them were executed a few years ago; therefore this specimen does not represent a perfect specimen of the art of ‘Nature’s Engraving.’ It will only direct the attention of the public again to this mode of making photography [popular; of bringing her productions to every house, every cottage, and perhaps to every library.; of making photographic pictures lasting and durable for centuries, and raising the photographer to the rank of an author.. I am of the opinion that “Nature’s Engraving” has been treated somewhat harshly – not by the public, but by certain persons who lay claim to an exclusive right to provide the people with photographs: But I still trust the good sense and discrimination of an impartial public. I still consider England as especially fit for carrying out such an important enterprise, although France has taken the lead in stimulating tho excretions of individuals in this direction. (4, 5)

1. Caption: I Pays! : Edgar Yoxall Jones: Father of Art Photography, O. G. Rejlander, 1813-1875: New York Graphic Society, Greenwich, CT, 1973: p. 47

2. Sources : Edgar Yoxall Jones: Father of Art Photography, O. G. Rejlander, 1813-1875; David and Charles, Newton Abbot (1973); A.G. Fielding, “Rejlander in Wolverhampton: His Sponsorship by William Parke“, History of Photography, Volume 11, Number 1, Jan-March 1987.

3. Sources: William Crawford: The Keepers of the Light, fig. 234 for a reproduction of “Richmond on Thames”, from Photographic Art Treasures, and pp. 281-283 for an outline of the process.

4. Courtesy Photogravure.com: Photogalvanography or Nature’s Engraving The Photographic Journal, Volume 6, No. 89 Sep 15 1859 P. 31

5. Courtesy Photogravure.com: Gernsheim, Helmut. The History of Photography: The Age of Collodion. London: Thames and Hudson, 1989. pp. 38-40