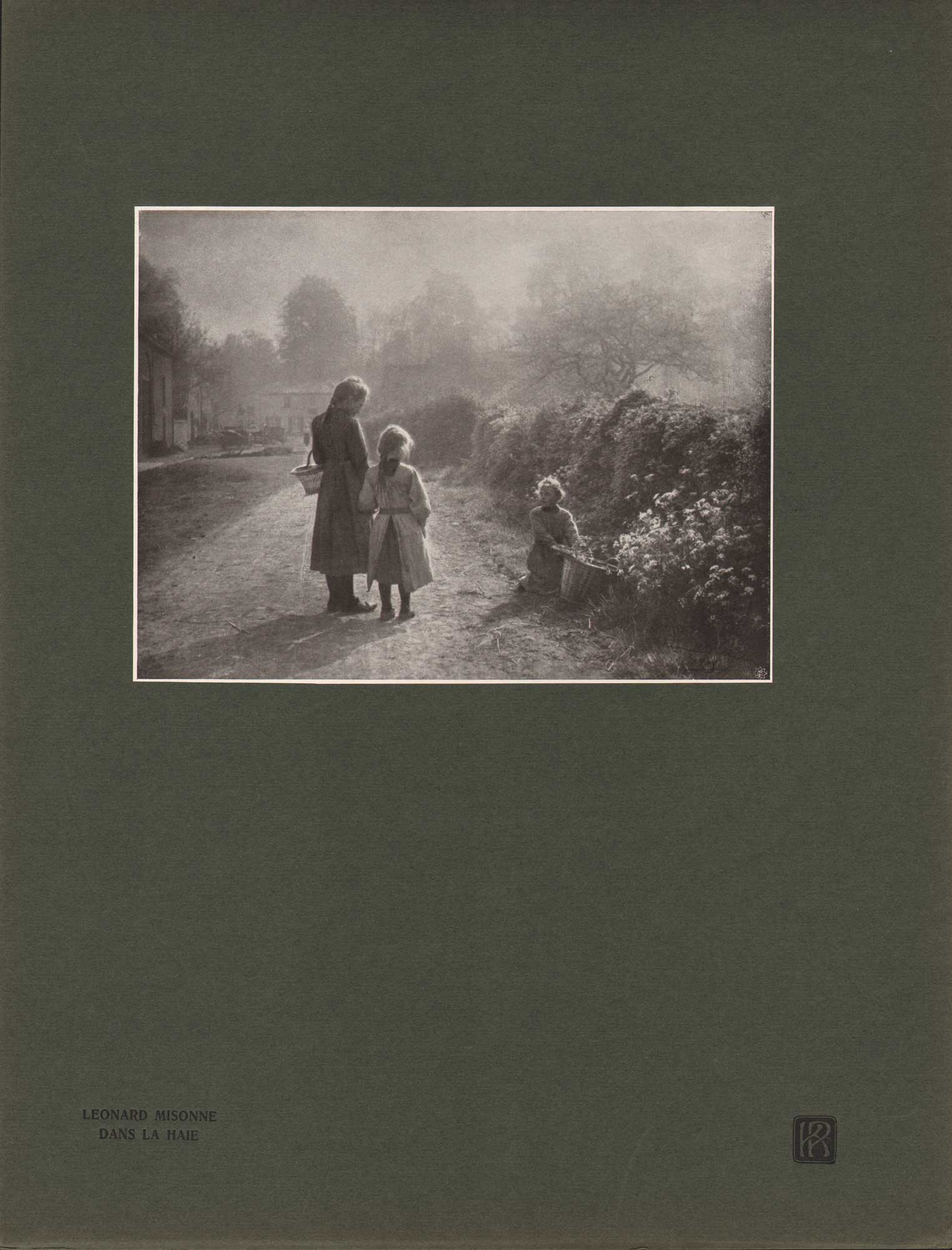

Dans la Haie | In the Hedge

A child picking flowers near a village hedge pauses while acknowledging the presence of two passing children. The photograph has alternately been titled by the artist En Passant, or, In Passing.

The following commentary on the artist’s photograph En Passant appeared as part of the series: MacSymon’s Commentaries, on the World’s Greatest Photographers: No. 4- Léonard Misonne, Belgium. It was published in the May, 1927 issue of the Boston journal American Photography:

EN PASSANT

As an object lesson, this superb picture of “figures in landscape” should offer example and inspiration to many thousands of readers. It is the last work in the delightful brochure of Léonard Misonne’s works, that has just been published, and ordinary as the subject matter may strike one, and threadbare the theme, it is a highly original work of artistry and poetry. The first function of Art is to be beautiful, – not “pretty,” but beautiful, and not only beautiful, but emotional. Look at this scene in a good light, and if your soul be not lost you will come to love it. It is a complete poem of feeling and meaning and rhythm. One could not coldly look on such a scene, as Misonne has given it, with every discordant note that is not required taken away, to leave all that is essential to the loveliness and the message. The children are not society’s darlings, nor film stars, but ordinary villagers in ordinary togs, and the scene is a plain village road of northern Europe, with a tempered view of humble houses and a hedge that might be anywhere, for there are hundred of hedges as fine. Nothing is pretty. The ingredients are plainest of the plain.

But there is morning haze and there is summer sun, and the children have come out to begin their day’s work or play, and they have arranged themselves into positions (or M. Misonne did it for them) of remarkable harmony with their surroundings, so that they make a fine

“intriguing” picture, with their background as a mere lovely setting. The lines and masses were arranged or selected by the artist. The sun did the rest.

The composition offers a very interesting problem, and this alone betokens the originality that has been called into play, and how far wrong are superficial critics who see little in such a work as this. There are strong radial lines leading to the vanishing point of the road and intercepting the heads of the standing pair, who are also seen in considerable contrast with their surroundings, and isolation. Yet unquestionably the seated figure is the dominant note of the composition! How is it done? Doubtless the picture is beautiful when the secondary figures are looked at, as it ought to be, but one ever returns to the little one on the grass. This ordinary little girl is transformed into a very beautiful object by the sun on her hair and to a lesser extent by its play on her frock and basket, against her considerable shadow area, through her position against the light. She glows against the hedge which recedes in the haze, and the little face, being the most human thing in the picture, draws us to it, glorified as it is by a halo, while the other plainer figures are inactive and averted. Another powerful note, placed with daring almost at the edge of the picture, is the contrasting bush of wild flowers. It also pulls interest to the right, and is only dominated by the stronger lines and firmer masses of the child who takes it as part of her belongings. Her cast shadow, and that of the other girls, points directly to her, also there are lines in the hedge leading down to her from the tree, and a significant dip in the contour of the far trees. Now with all these reasons for principality, something drastic had to be done to lessen the pull in her direction, for principality can be overdone. So, M. Misonne arranged strong lines to emanate from the region of the secondary group, veiling them in the mist to avoid excessive attraction, and taking care to reserve the brightest accents and crispest definition for the little flower gatherer. He has made something of a cart rut to connect the figures and, feeling that the child’s face was too isolated and too like the others, he put in a second group of flowers immediately behind it, making a symbolic wreath, and qualifying the otherwise too insistent group of flowers in the foreground. It is the pull of one thing against another that makes a work of art interesting and emotional, and the pull of the main radial lines would have been so strong had the mist, or rather, the haze, cleared, that the picture would have failed. Seen from too great a distance, the pair show out first, but interest then becomes focused on the little one, but at a reasonable distance the child immediately assumes command. Either way it is beautiful and an object lesson in the spontaneous posing of figures and their relation to the sunlight. (pp. 262-64)

Léonard Misonne: 1870-1943

Léonard Misonne was a Belgian pictorialist photographer. He is known for his landscapes and street scenes with atmospheric skies.

Photography: Misonne is best known for his atmospheric photographs of landscapes and street scenes, with light as a key feature, and as a pioneer of pictorialism. According to the Directory of Belgian Photographers, “Misonne’s work is characterised by a masterly treatment of light and atmospheric conditions. His images express poetic qualities, but sometimes slip into an anecdotal sentimentality.” He was nicknamed “the Corot of photography”.

Misonne devoted himself to photography from 1896, joining the Belgian Photography Association in 1897. He became a leading light in pictorialism, frequently exhibiting his photographs at exhibitions. He also did slide shows. Much of his photography was in Belgium and the Netherlands, but he also visited London, France, Germany and Switzerland. The German occupation of Belgium during World War II greatly restricted his photography.- Wikipedia (2024)

Additional historical as well as exhibition history for Léonard Misonne can be found courtesy of the Directory of Belgian Photographers hosted online by Fotomuseum Antwerp. (FOMU)