The Summer Sea

The Summer Sea was copyrighted in 1903 by the Alfred S. Campbell Art Co. of Elizabeth, New Jersey. It might be considered a manipulated print, in that the original negative by American pictorial photographer Rudolf Eickemeyer Jr. (1862-1932) was printed by the firm and then hand-colored. For example, the Sun overhead has been drawn in by hand, along with many of the highlight areas in its reflection onto the waves and sand in composition foreground. The picture is sometimes mistaken for a nighttime photograph of a rising full moon. The work is a later variant by the photographer titled A Summer Sea, taken in 1901 and held by the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C.

Rudolf Eickemeyer Jr.: 1862-1932

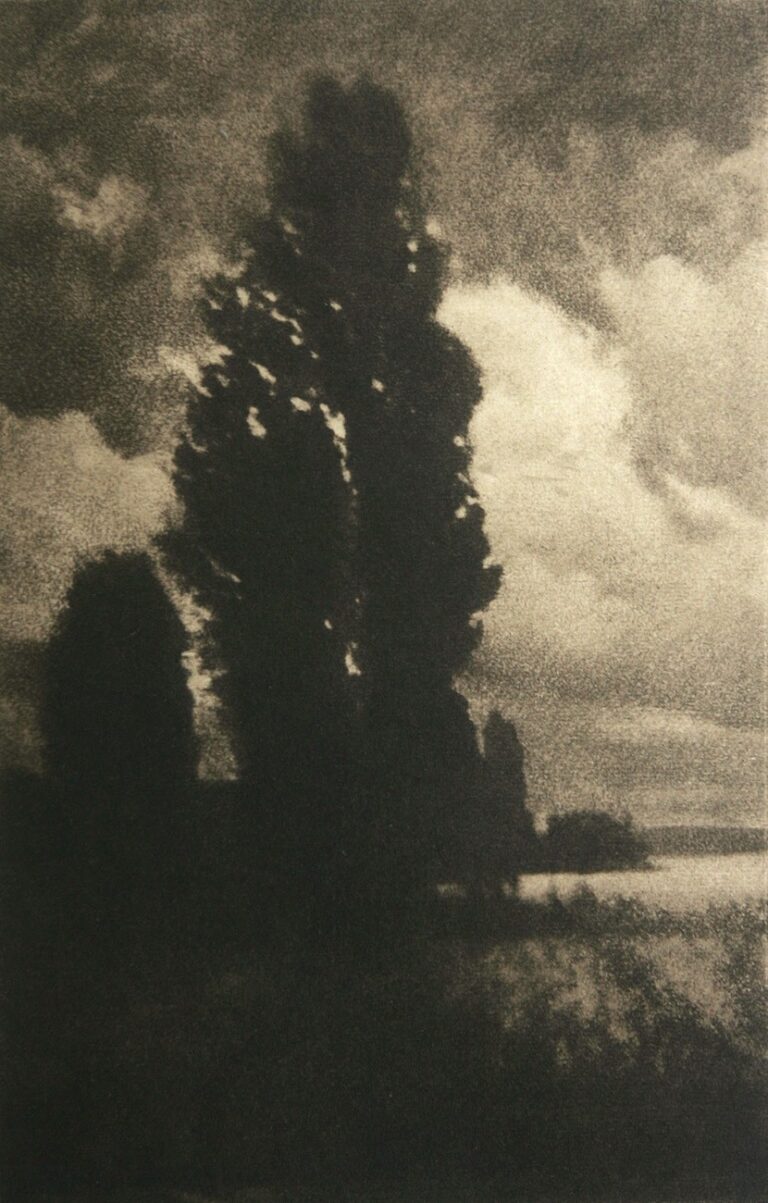

Eickemeyer was an American pictorialist photographer, active in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He was one of the first Americans (along with Alfred Stieglitz) to be admitted to the Linked Ring, and his photographs won dozens of medals at exhibitions around the world in the 1890s and early 1900s. He was famous among his contemporaries for his portraits of high-society women, most notably model and singer Evelyn Nesbit. Eickemeyer’s best-known photographs are now part of the collections of the Smithsonian Institution.

Life: Eickemeyer was born in Yonkers, New York, in 1862. Though widely travelled, he would live in Yonkers his entire life. Eickemeyer’s father had fled to New York in the early 1850s following political upheavals in his native Bavaria, and became a noted inventor. His firm, Osterheld and Eickemeyer, invented a hat-blocking machine that revolutionized the hat industry, and made a number of advancements in electrical lighting.The younger Eickemeyer joined his father’s firm as a draftsman in 1879.

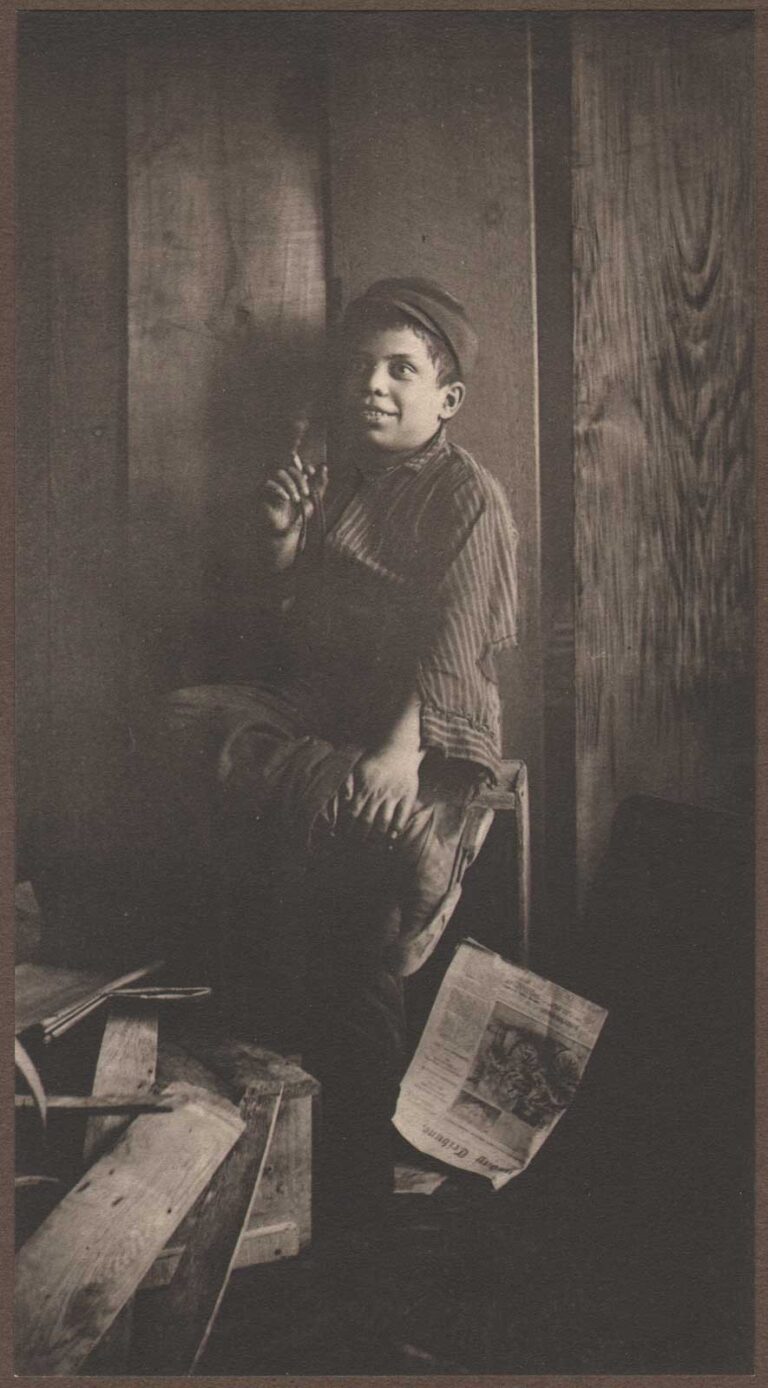

Eickemeyer first became interested in photography as a means to help document his father’s inventions. He purchased his first camera, an “abnormally thick” Platyscope B, on February 2, 1884, and took his first photograph, an albumen print of his sister, the following day. Immediately drawn to the camera’s artistic potential, Eickemeyer considered pursuing a career as a photographer, but his father disapproved, so he continued working for his father’s firm.

Eickemeyer won 11 medals at the Yonkers Photo Club’s Lantern Slide Exhibition in October 1890, and over the subsequent decade, he collected over a hundred medals at exhibitions and salons around the world. After his father’s death in 1895, he left his father’s firm and joined the Carbon Studio in Manhattan,which specialized in portraits, and gained a reputation for photographs of high-society women. That year, he and Alfred Stieglitz became the first Americans admitted to the English pictorialist society, the Linked Ring. While Eickemeyer’s work appeared in Stieglitz’s Camera Notes, he was unimpressed with the rise of the Stieglitz-led Photo-Secession early in the following century. He was one of four Links who never joined the Photo-Secession, the others being F. Holland Day, Margaret Russell Foster, and C. Yarnall Abbott.

In 1900, Eickemeyer joined the New York Camera Club, and exhibited 154 frames in his first one-man show at the club. That same year, he published his first book, Down South, and was appointed art manager of the Campbell Art Studio on Fifth Avenue, with which he would remain intermittently until 1915. It was while at Campbell that Eickemeyer conducted his famous shoot of New York model Evelyn Nesbit. -Wikipedia (2024) continues…

Campbell Art Co.

The following history of the Campbell Art Company is courtesy of and written & compiled chronologically by Mark Strong of Meibohm Fine Arts, Inc., East Aurora, New York.

Campbell Art Company (AKA Alfred S. Campbell Art Company, Campbell Studio & Campbell Prints, Inc., American Publishers, c.1871-c. late 1930s) was originally founded by Alfred S. Campbell (English-American, 1840-1912) who was an English art photographer and commercial inventor. In 1867, Campbell was invited to come to the United States where he formed a partnership with Napoleon Sarony, under the Sarony name. Sarony had a great desire to gain access to Campbell’s patented photographic process, but within four short years, their business relationship dissolved. Campbell soon decided to move to New Jersey, where he built his state-of-the-art studio which had an onsite photo imaging production facility in Elizabeth, NJ initially calling it ‘Campbell Studios’. Aside from his art studio and patented photographic process for platinum photo-printing, Campbell also invented a panorama lens and held numerous patents for cameras and various paper products.

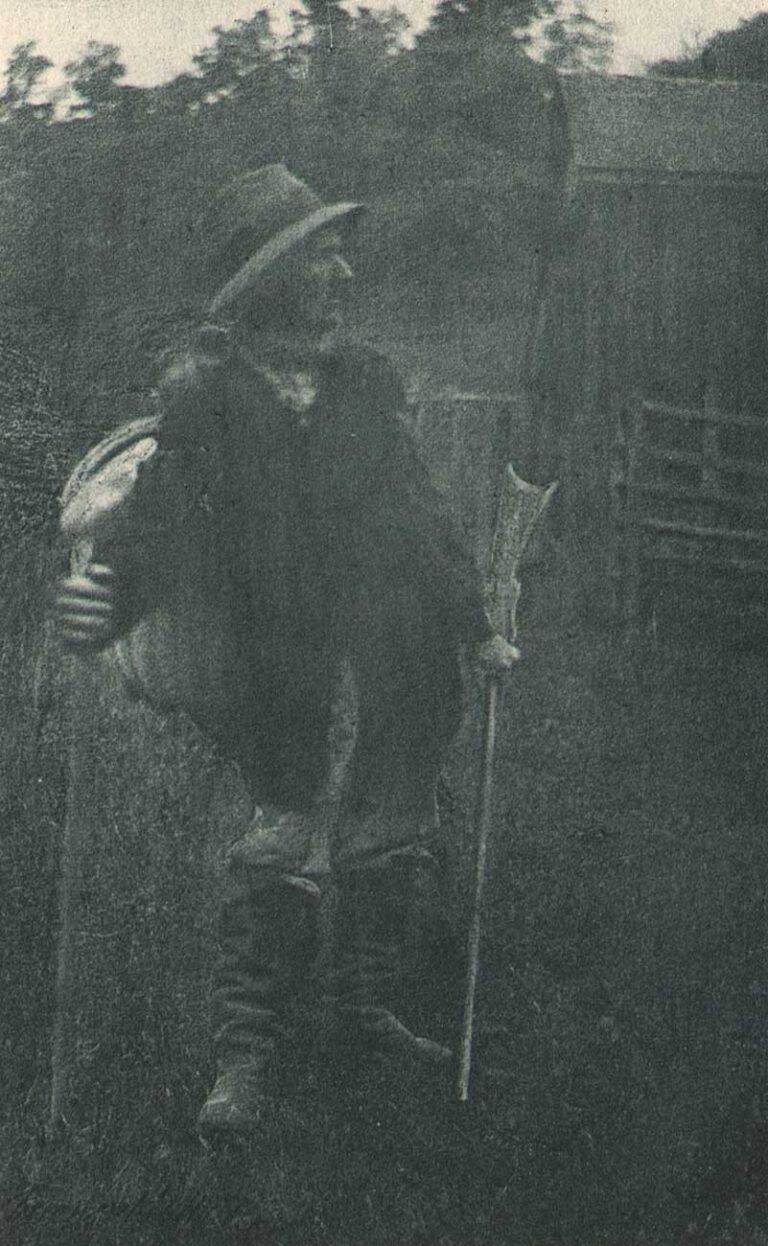

Over the years, the company specialized in reproductions of well-known artists’ works, chromolithographs, various hand-colored prints & photographs finished in watercolor & oil, ‘Apographs’ (hand-colored rich brown photo-gelatin prints), platinum & carbon prints, stereograph cards, scenic views, postcards, portrait cabinet cards as well as portrait and theatrical photography for stage & screen, “Washington Prints” which included the best of the mural decorations in the Congressional Library, as well as Campbell’s patented “Art-Relievo” platinum photographic prints which were 3-dimensional photographic reproductions in ‘absolute relief’ (embossed) that he sold in the late 1890s through the early 1900s (c1896-c1904). Campbell reproduced various master works, Native American Indian portraits/scenes, religious/inspirational scenes, genre scenes, boudoir images etc., by way of the Art Relievo process. What is also interesting about the Art Relievos is that, Campbell initially worked with the Carbon Studio in Manhattan, but soon hired one of their top employees, the well-known American pictorialist photographer, Rudolf Eickemeyer, Jr. (1862-1932) who later became art manager of Campbell’s portrait studio at 564-568 Fifth Avenue in New York. While there, Eickemeyer, Jr. produced many of the early Art Relievo prints, carbon & platinum prints, as well as prints in watercolor, oil etc., and remained at Campbell Studios intermittently until 1915. The Art-Relievo prints came in various sizes (6.5 x 8″ up to 15 x 60″) and they were pretty expensive back in the day, ranging in price from $2-$50 each ($72- to $1,819- in today’s dollar for 2023). For whatever reason the Art Relievos seemed very short-lived; possibly because they were too expensive to make (with the molds & mold-machines needed), and many were sold with the extra deep frames which drove up cost too, or maybe people just couldn’t afford them or they proved to be unpopular with the public—not sure… On the open market, the Art Relievos don’t tend to bring much at auction or via other online resources unfortunately, possibly because most people, various collectors or even many antique/fine art dealers don’t really know what they are, but they are definitely an interesting and very cool patented print-process that should hopefully become more-collectible with time.

The Alfred S. Campbell Art Company also had gallery ‘Art Rooms’ located at 377-379 Broadway in New York City, their portrait studio located at 564-568 Fifth Avenue as well as a prints division called Campbell Prints, Inc., located at 33 West Thirty-Fourth Street, and at 59 West 19th Street. There were also divisions in Baltimore, MD and Charlestown, WV.

By 1900, the Alfred S. Campbell Art Co. had branched out under the direction of William A. Morand in Manhattan at 538 5th Avenue which was called Campbell Studio. Morand had family & social connections in New York and built it into one of the most dominant companies in Manhattan at that time. Morand made a name for himself as one of the leading portraitists in the city. After Morand’s death in 1909, the company took an interest in theatrical photography and furthered their success with the entertainment industry with innovations in the new style of celebrity photography and portraiture.

By 1915, the company specialized in half-length portrait photos of screen and stage stars in the very fashionable dress styles of the times. They routinely supplied theaters and magazines with their photographs. They were a large force in the entertainment industry, but by 1925 the company had to take a corporate charter for $25,000 and by 1928 the company’s entertainment market had ended. They did manage to continue a commercial portrait studio through the 1930’s.