No Slouching Please: Posture Training in 1910

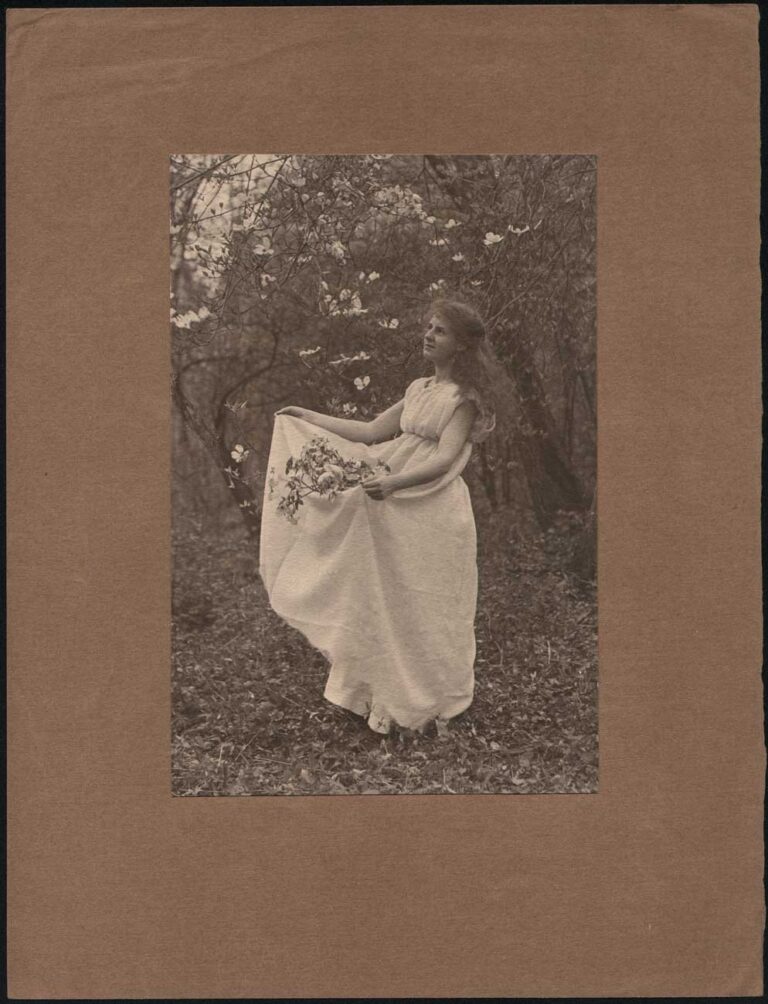

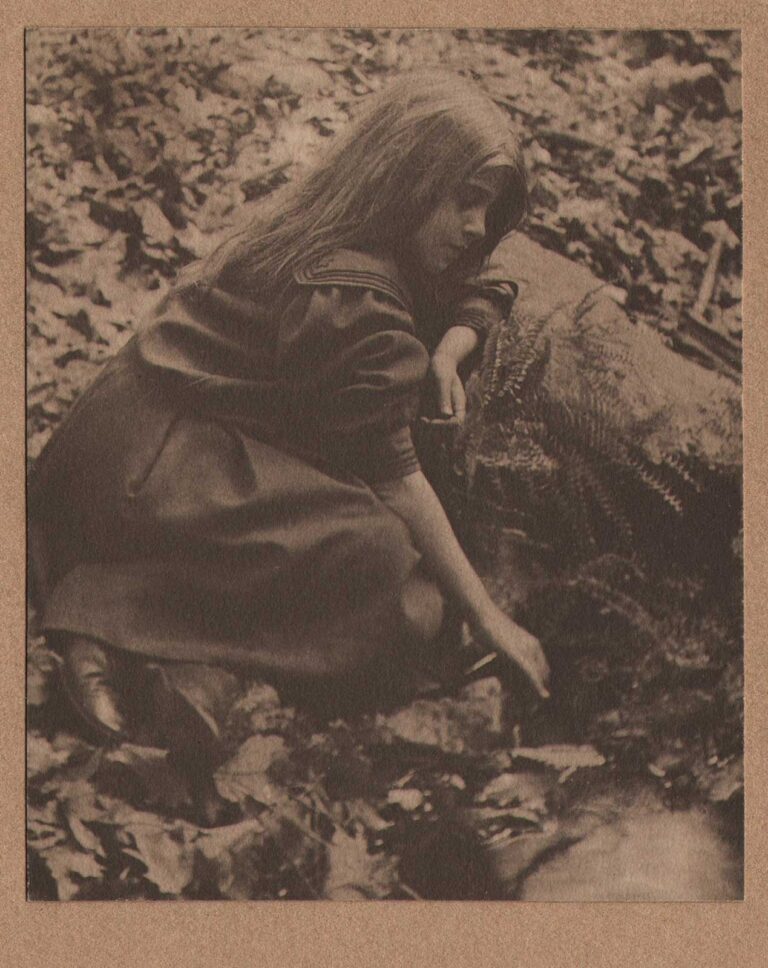

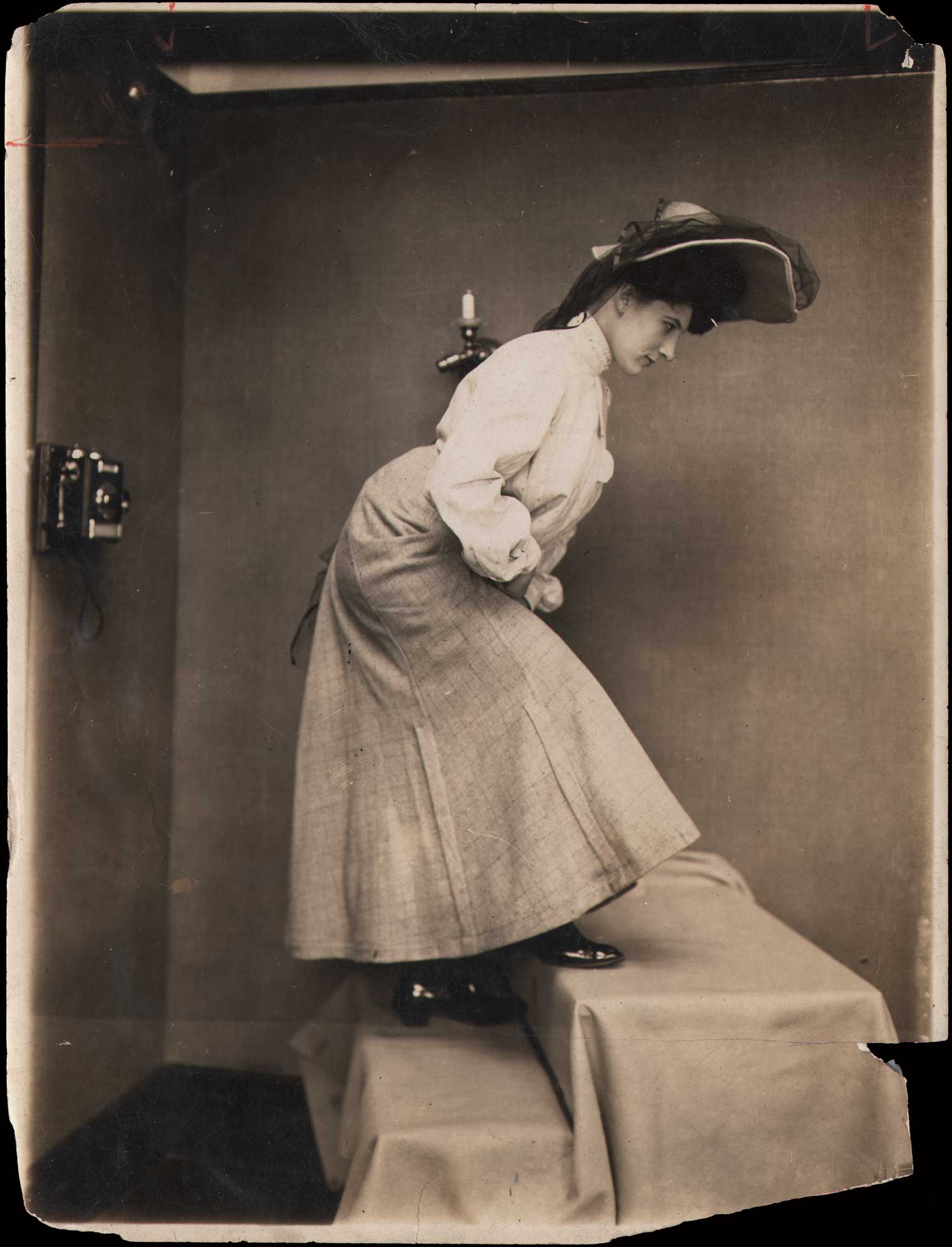

As it turns out, this young woman from around 1910, who deliberately shows off her poor posture while climbing a set of steps, could make a living, or at least a day rate, as a posture model. This is not the type of image this archive typically collects, but sometimes an early photograph, or any photograph for that matter, can break the bonds of its original context and become art.

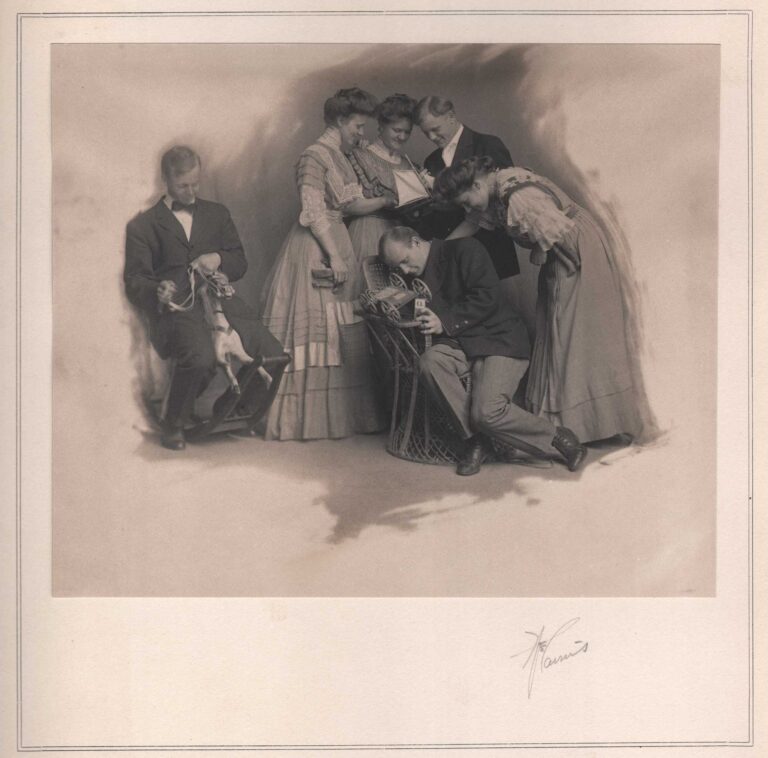

With the intent of her fixed gaze and large hat, the studio walls featuring an early wall-mounted telephone at left and candle sconce behind, the arranged tableau combines mystery and delight while offering more questions than answers for a modern viewer seeking clarity 115 years in the future.

So don’t knock slouching. Her posture strikes this archive owner as another example, albeit five decades previously, of a similar type of “photographic evidence”, found in the photographs compiled by Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel for their 1977 masterwork Evidence.

Described as works singled out from “thousands of photographs in the files of the Bechtel Corporation, the Los Angeles Police Department, the Jet Propulsion Laboratories, the US Department of the Interior, Stanford Research Institute and a hundred other corporations,” these were “photographs that were made and used as transparent documents and purely objective instruments—as evidence, in short.” Martin Parr also summed up their significance nicely, in The Photobook: A History, he weighs in on Evidence: “A visual conundrum of incalculable mystery.”

Posture Training: Evidence of the Movement

Believe it or not, the idea of proper posture, particularly as it applied to personal health, schoolchildren, and later for those going off to fight in war, was a trending movement in the early decades of the American 20th Century. Here are excerpts from two articles to get you thinking about posture training, should you want to learn more about the intent of why we have evidence from 1910 of a young woman slouching up stairs.

“As the 20th century began, leading experts on posture argued that poor posture was the culprit for a variety of acute and chronic illnesses, caused by putting unhealthy pressure on the internal organs. The condition was given a clinical name: viceroptosis. Posters declared, “Poor posture encourages tuberculosis. Erect carriage combats it.”

Having a slouched form, in this time period that became known as the Machine Age, was considered a “disease of civilization.” Fewer people held down jobs that required physical strength, more lived in cities, and children were mandated to attend school rather than work on farms.” (1.)

“At the same time, posture tests became increasingly standardized in the 1910s as university physician-researchers developed tools and technologies to assess human physiques. Dr. Clelia Mosher (cousin of Eliza Mosher) of Stanford University and Dr. Lloyd T. Brown of Harvard both developed visual recording methods to grade postures, converting the data into statistical numbers that provided quantitative proof of the poor posture epidemic (see fig. 2). These visual recording techniques were also adopted by military draftee boards once the United States entered the Great War in the spring of 1917.” (2.)

- Excerpt: Penn Today, Examining 20th-century America’s obsession with poor posture, a forgotten ‘epidemic’: Professor Beth Linker’s next book concerns itself with the nation’s now-faded preoccupation with hunched, slouching bodies, June 7, 2018

- Excerpt: Jaipreet Virdi, Mara Mills, Sarah F. Rose University of Chicago Press, Sep 2, 2024, Osiris, Volume 39: Disability and the History of Science