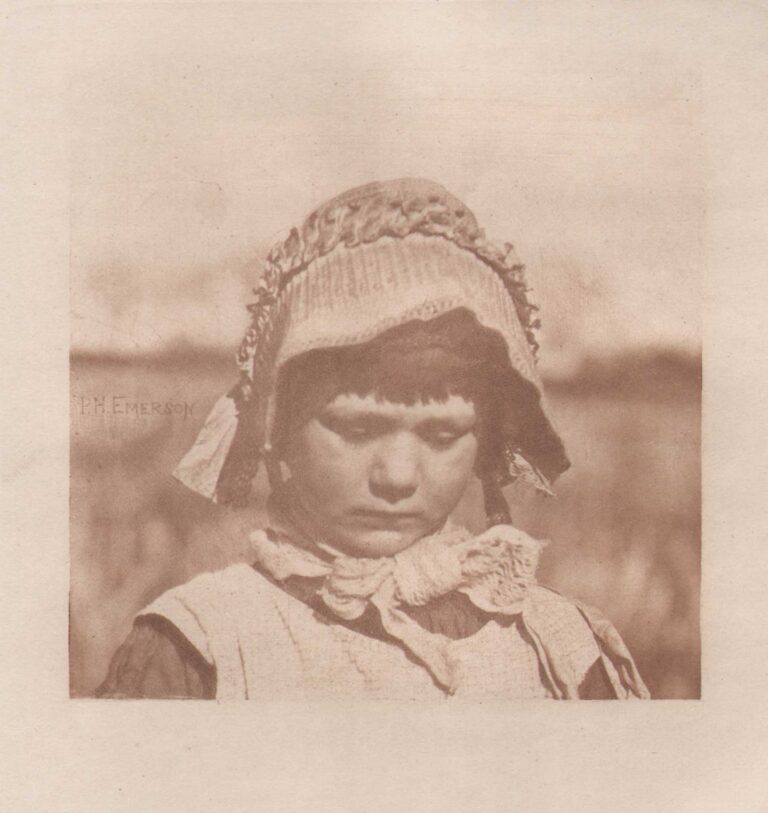

Brickmaking {Norfolk}

From Chapter XIX: Brickmaking

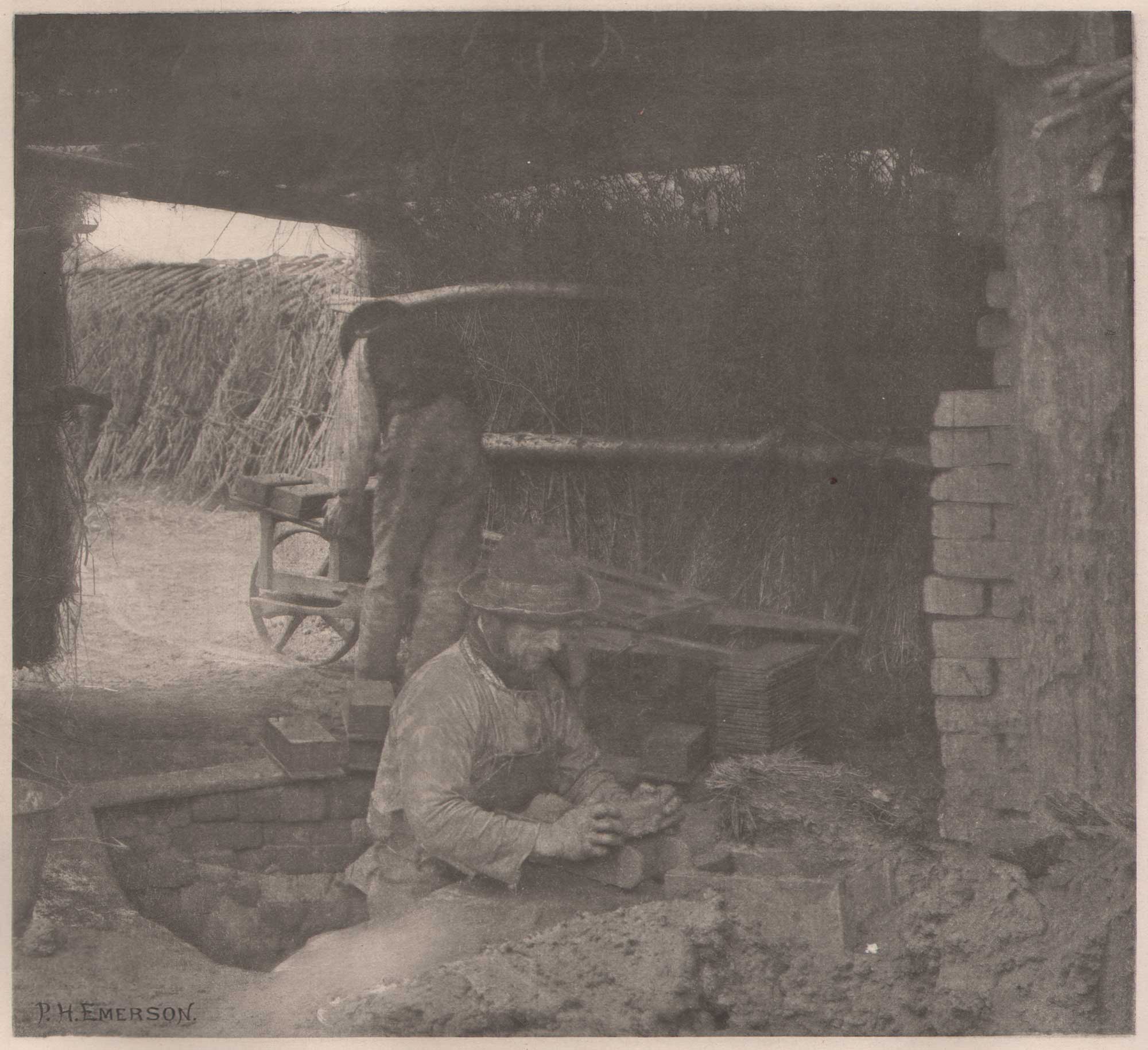

“We saw our opportunity had come, so we proposed our terms. If they would assist us in making one or two pictures, we promised there should be plenty of beer for all hands. One sharp fellow spoke for the rest and agreed. He is the model making a brick.

In this plate the operator will be seen standing in a hole in the ground inside a roughly built standard with its two doors. Before him is a counter on which he works. To his right stands a heap of ground clay and a bucket of water. In front of him are piles of small brick boards, each a little larger in area than the flat side of a brick; whilst on his left is a small oven in which a fire can be made by which to dry the finely ground clay used to sprinkle over the brick and board to prevent the new clay from sticking. A spade and bucket for working the clay stand in another part of the hut. The heap of clay near the hut comes from the clay-mill, and is roughly worked with spade and water afterwards by the brickmaker. His tools are a frame called a mould (which is a box), whose internal measurements are the exact size of a brick, without lid or bottom; and a slice, a short rounded stick, not unlike a rolling-pin. He begins by placing his mould before him on a board, and his slice into a bucket of water. Then he takes lumps of clay and fills the mould till it is quite full, then with the slice he shaves off all the clay projecting over the mould, and so forms a flat surface, while the counter on the other side forms the other flat surface; then taking one of the small brick boards, he places it as a cover over the mould, quickly turns it upside down, and removing the mould, leaves the newly made brick exposed on the board. He dusts it lightly with clay and puts it on one of the barrows, the boy belonging to which waits until the regulation load of twenty is ready, when he wheels it off to the shambles, where it remains for nine days and nights if the weather be dry.

The operation reminded us strongly of making pastry, and we asked if women could not do the work. “Yes,” was the answer, “they used to do it, but do so no longer,” no reason being given for their cessation from the work. An average workman can make fifteen hundred bricks a day, for which he gets five shillings per thousand for red bricks, while for white bricks he gets two shillings per thousand more. We examined the workmen’s hands for warts, but they had none, but at times they get fearful cuts from “Bits of stuff” in the clay.” p. 116