Marsh Leaves

Much has been written of P.H. Emerson’s final volume of masterful photographs reproduced in photogravure titled Marsh Leaves, published in 1895. The source material came from 16 earlier plates taken by the artist in 1890-91 during his one-year cruise aboard the wherry Maid of the Mist while navigating and exploring the Norfolk and Suffolk Broads. Beginning in the late 1880s and during this period he was also learning the art of photoengraving from Walter L. Colls. His 1893 volume On English Lagoons would be the first illustrated with plates etched and printed by himself, followed by these more refined and nuanced East Anglian scenes translated into delicate photogravure impressions.

“Emerson’s final photographic book Marsh Leaves was published five years after he renounced the belief in photography’s fine art status. In many ways paradoxically his most artistic volume, it is comprised of his most personal writings, only obliquely linked to his most exquisite images of pure landscape. Self-consciously composed as a conclusion for his decade in the photographic arena, it is his final statement of art and life, as well as a farewell to the private pictorial sphere that East Anglia had been to him.“—Ellen Handy: Imagining Paradise: The Richard and Ronay Menschel Library at George Eastman House, 2007. p. 193

Limitation

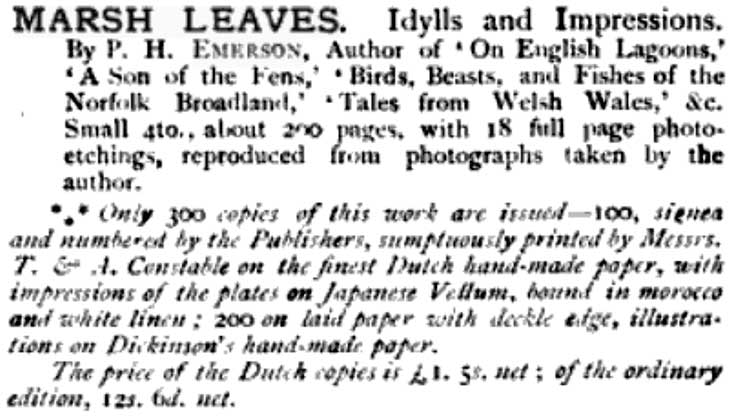

Earlier in 1895, the London publisher David Nutt took out the following advertisement, which appeared as part of their holiday book offerings in The Publishers’ Circular, Christmas 1895. As one can see, the title and number of plates for Marsh Leaves would be altered, with the subtitle “Idylls and Impressions” dropped from the cover title and gravure plates reduced from 18 to 16.

MARSH LEAVES. Idylls and Impressions. By P. H. EMERSON, Author of ‘On English Lagoons,’ ‘A Son of the Fens,’ ‘Birds, Beasts, and Fishes of the Norfolk Broadland,’ ‘Tales from Welsh Wales,’ &c. Small 4to., about 200 pages, with 18 full page photo-etchings, reproduced from photographs taken by the author. Only 300 copies of this work are issued—100, signed and numbered by the Publishers, sumptuously printed by Messrs. T. & A. Constable on the finest Dutch hand-made paper, with impressions of the plates on Japanese Vellum, bound in morocco and white linen: 200 on laid paper with deckle edge, illustrations on Dickinson’s hand-made paper. The price of the Dutch copies is £1. 5s. net; of the ordinary edition, 12s. 6d. net.

Contemporary Reviews

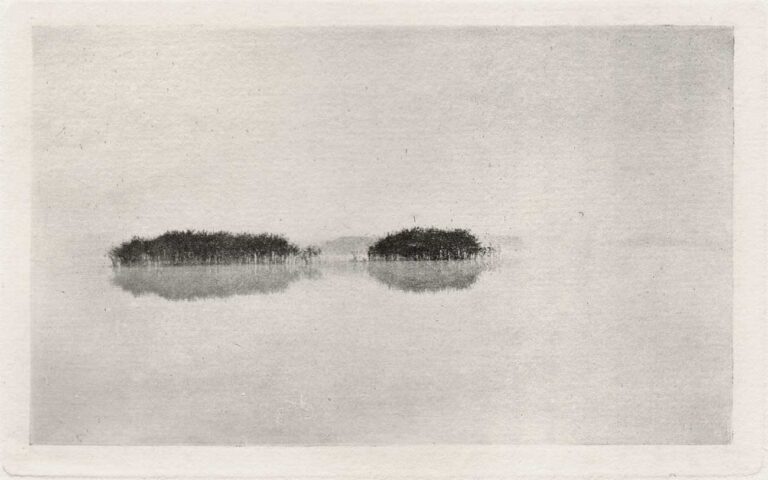

Reviews of Marsh Leaves were for the most part laudatory, although some critics seemed unsure how to characterize these impressionistic photographs, with one reviewer, EX CATHEDRA, stating that certain plates, including the now acknowledged Emerson masterpiece The Lone Lagoon, should have been left out of the volume “on account of their unintelligibility”.

The Studio: An Illustrated Magazine of Fine and Applied Art, Vol. 7, 1896

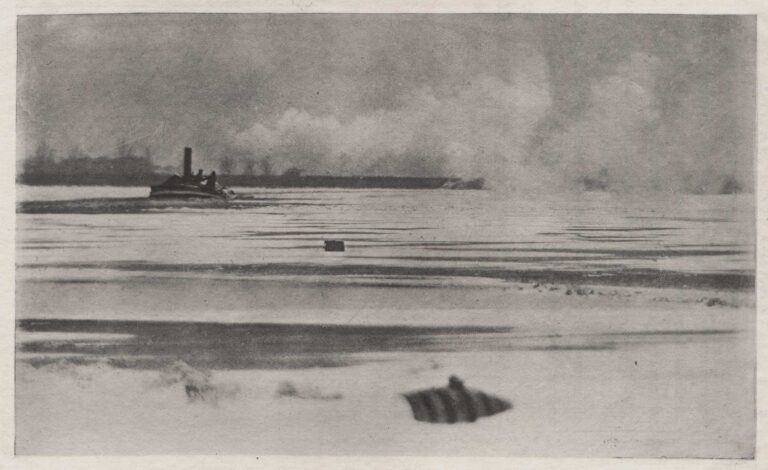

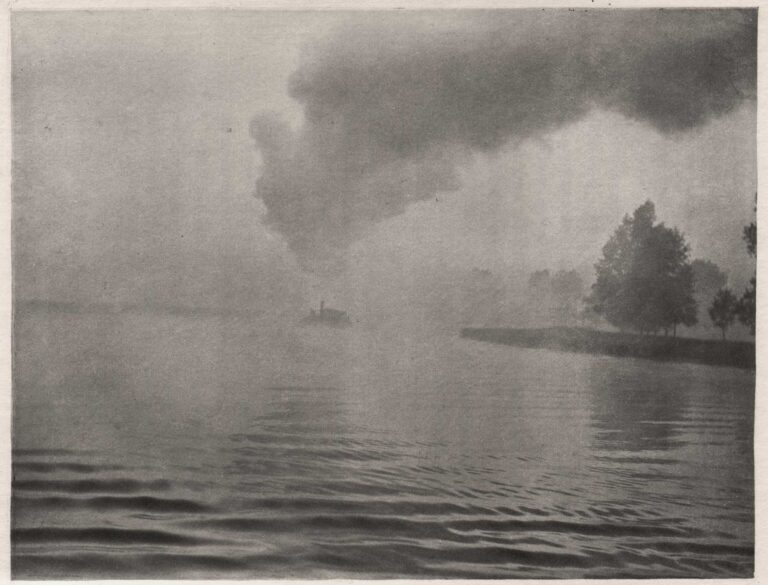

“Marsh Leaves. By P.H. Emerson, with sixteen photo-etchings from plates taken by the author. (London: David Nutt.)-The distinguished writer of “Naturalistic Photography” has long since been acclaimed by those cultured in pictorial art as one whose productions, albeit they come from a camera, are instinct with a larger proportion of graphic quality and suggestion than is usually associated with a photograph. The photo-etchings in Marsh Leaves will go far to widen the existing gulf which yawns between the crowds who depict too much of everything with harrowing insistence, and the few, such as Dr. Emerson, who impose upon their records an impressive reticence. The author has kindly allowed us to reproduce in “half-tone ” two of the illustrations to this book.” (1.)

The British Journal of Photography: January 10, 1896

Another review of the volume, in the weekly British Journal of Photography, is instructive today for how readers may have entertained prospects of purchasing the volume. In this regard, the writer, under the Latin pen name EX CATHEDRA, (with authority) seems more interested in dissecting Emerson’s prose abilities than his photographic efforts. Unfortunately, his so called “authority” seems also to have been tripped up by the term “photo-etchings”. Here they state “possibly photogravures” for the method employed by Emerson in their reproduction method.

EX CATHEDRA.

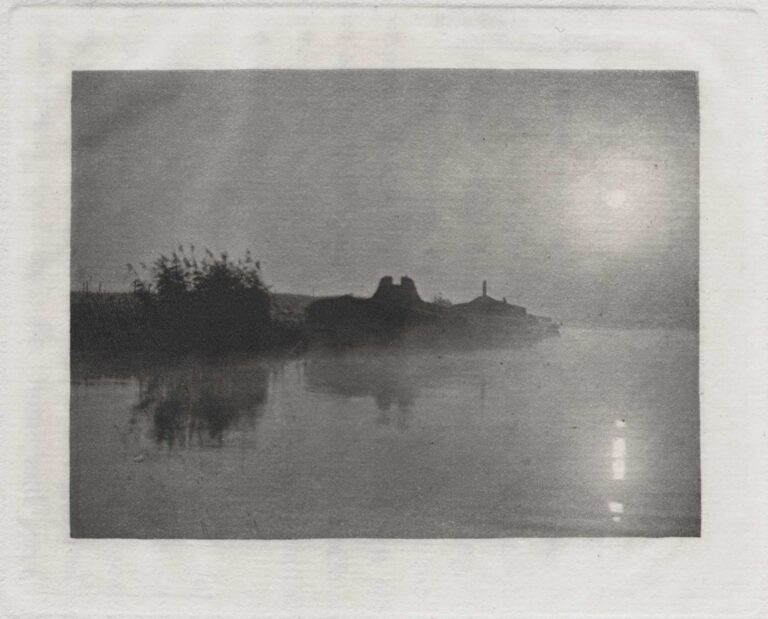

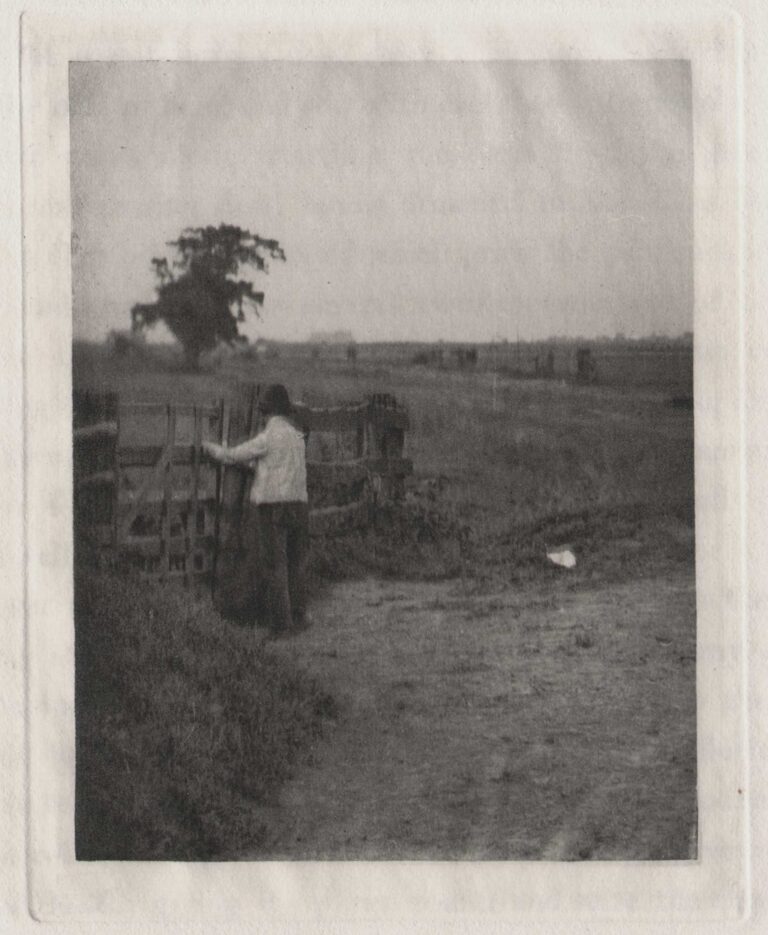

“Dr. P.H. Emerson’s last book, Marsh Leaves (London: David Nutt) is a beautiful production as books go, but in some essentials it is disappointing. It may best be described as a series of word vignettes of nature and character in the East Anglian fens. Here and there the author’s prose paintings are so realistic that we seem to breathe the very air of the scenes he describes. Notably is this so of the chapters headed “A Moonlight Midnight,” “First Voice of Spring,” “Return of Spring,” and “A Nocturne,” which attest both Dr. Emerson’s accuracy and minuteness of observation, and his skill in delineating the smallest details of his subjects.

Humour, pathos, and human sympathy distinguish the chapters in which the author deals with character as found in fenmen, wherrymen, and marshmen. Dismissing several chapters in which the scenes and incidents handled are either commonplace or inconsequential, it struck us that, were Emerson to devote himself to fiction, he would find congenial work in doing for East Anglia what Blackmore has done for Devonshire and Cornwall, and what Thomas Hardy has done for Wilts and Dorset, that is, to make the country, with its customs, manners, dialect, and character, the background of a series of fine novels. His obvious powers, in combination with the years of patient observation he has expended, mark him out for such an undertaking.

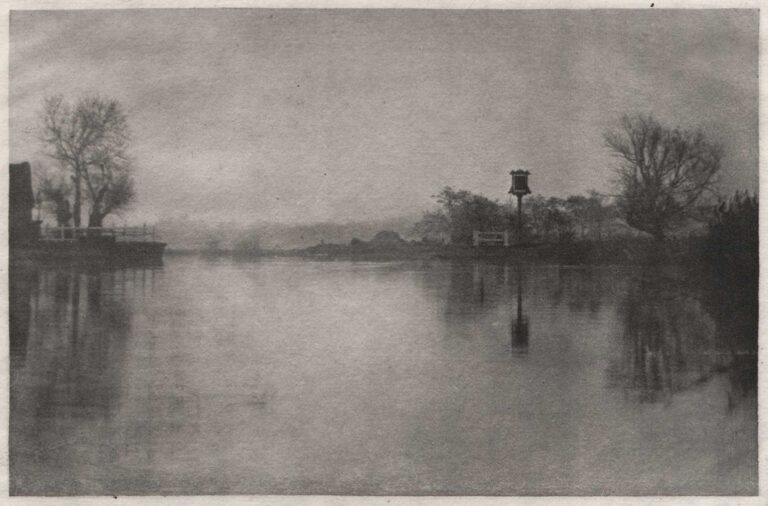

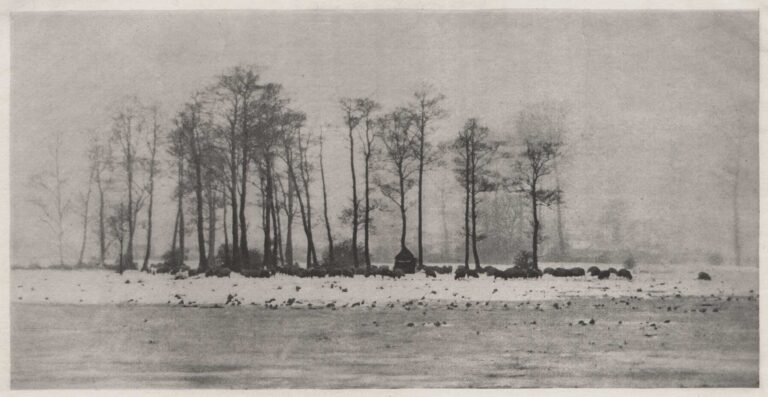

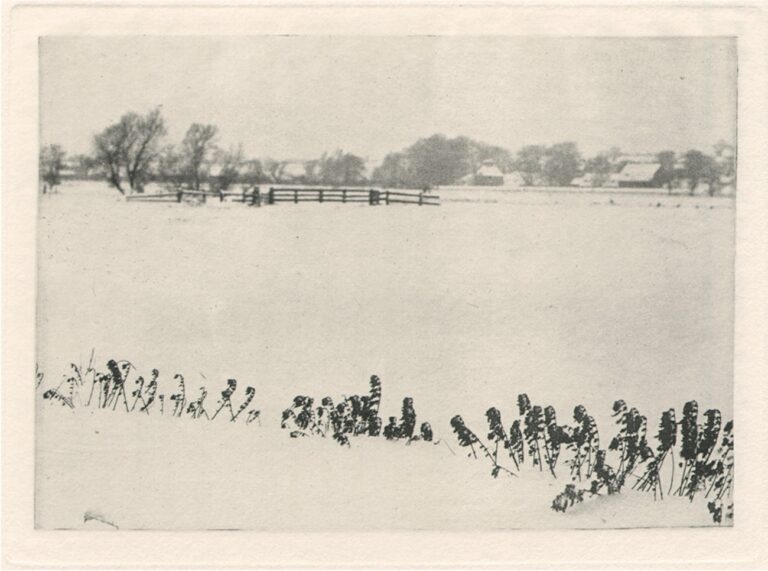

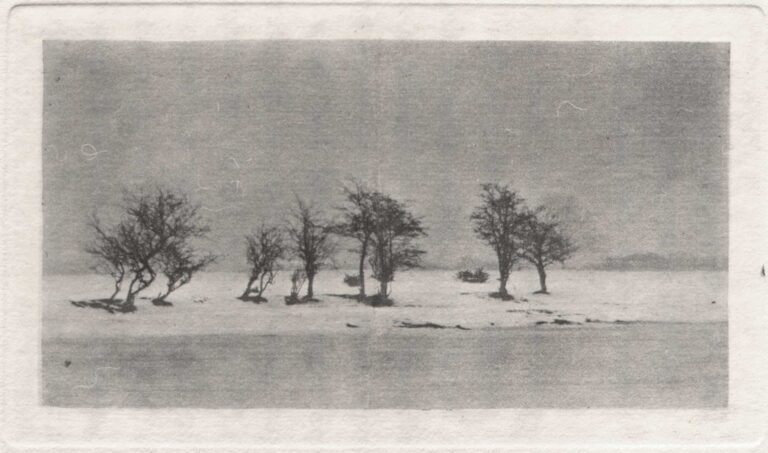

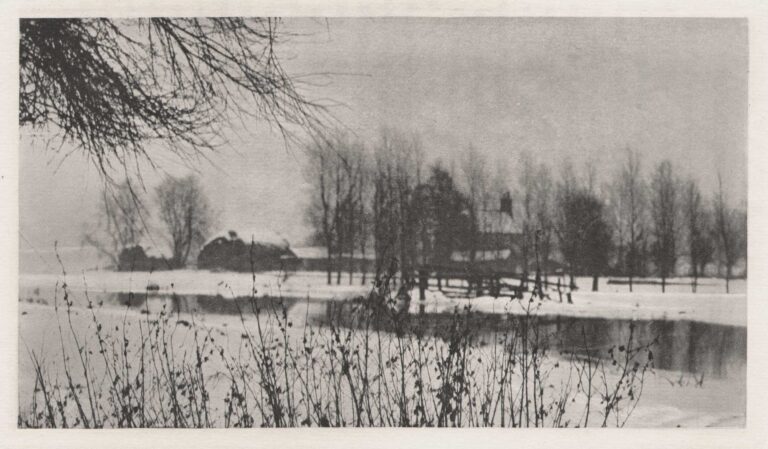

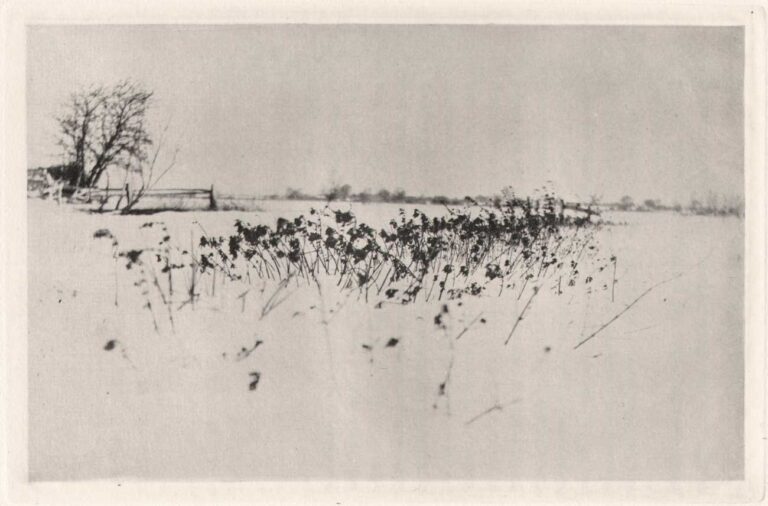

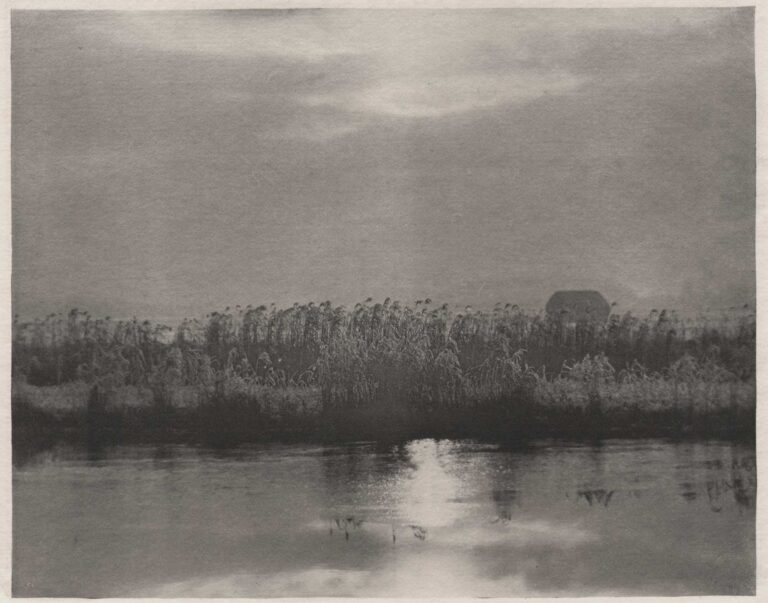

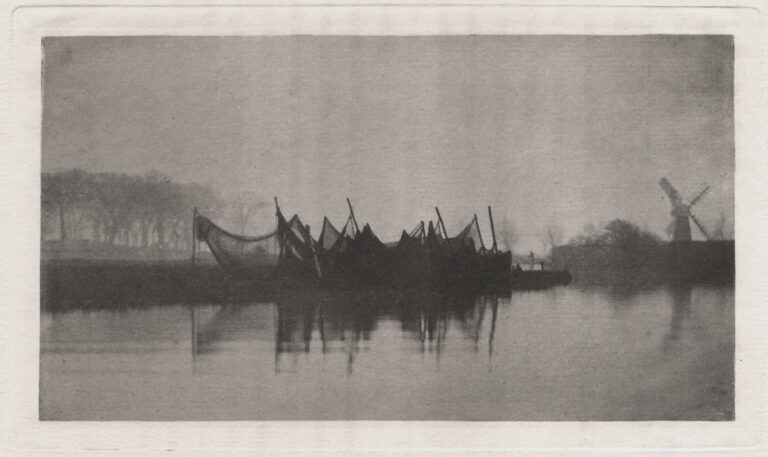

There are “sixteen photo-etchings from plates taken by the author” to illustrate “Marsh Leaves,” possibly photogravures, but looking not unlike collotypes on plate paper. The frontispiece is “A Winter’s Sunrise,” an enlargement of which, we believe, was shown at the last Exhibition of the Royal Photographic Society. We may instance the “Lone Lagoon,” which shows two little bits of tree-topped shore surrounded by a monotonous area of faintly inked paper, as an example of some of the illustrations that might, on account of their unintelligibility, have been omitted ; on the other hand, “ A Winter Pastoral ” and “ Bleak Winter,” two snowy landscapes with gaunt trees, the atmosphere of winter brooding over scenes of dreariness, are in the author’s best manner. “Marsh Leaves” is an uneven but an interesting book.” (2.)

Photograms of the Year, 1896, p.18

“One other book with delightful photographic pictures that requires mention is “Marsh Leaves,” by Dr. P.H. Emerson. The pictures, in photogravure, are mere slight camera sketches, suggestions rather than finished works, but they all betray the hand of a master in their selection, and prove, if it had never been proved before, that the camera is not by any means a mere recorder of fact.”

Commentary: Present Day

In the present day, Marsh Leaves has become the defining album of P.H. Emerson’s masterful vision, evoking superlatives by those ascribing reverence for the misty Broadland landscapes contained within. From the Musée d’Orsay, Paris:

“Marsh Leaves, Emerson’s last album and his masterpiece, is the most radical demonstration of how this photographer’s art had developed, moving from an initial Naturalist approach to a very refined graphic style. Nevertheless, the Japanese influence was already evident in his work in photographs such as The Snowy Marshlands published in 1893 in the collection On English Lagoons. Furthermore, after 1886, Emerson revealed a certain fondness for flat compositions and graphic effects, most notably in A Rushy Shore, one of the plates in his first album, Life and Landscape of the Norfolk Broads. We should certainly acknowledge the influence of the French Impressionists here, in particular of Monet, a great collector of prints, and of the British-based painter Whistler whom Emerson knew personally.”

From later in the 20th Century, the famed curator and art historian Beaumont Newhall:

“It does not seem possible these images were made in 1890-91; he seems to have entered a whole new period of the perception of form, detail, composition. He belongs with Monet and the Post-Impressionists and even anticipates much later periods in art–the early Abstractionists, for example.” Marsh Leaves is one of the most beautiful books about isolation, solitude, and, perhaps, death ever made, and Emerson’s spare evocative photogravures propelled the new medium of photography into the realm of fine art.“

- Reviews of Recent Publications: The Studio: An Illustrated Magazine of Fine and Applied Art: Vol. 7: London, 1896, p. 54

- Review: Marsh Leaves: The British Journal of Photography: London: published by Henry Greenwood & Co.: January 10, 1896, p. 17