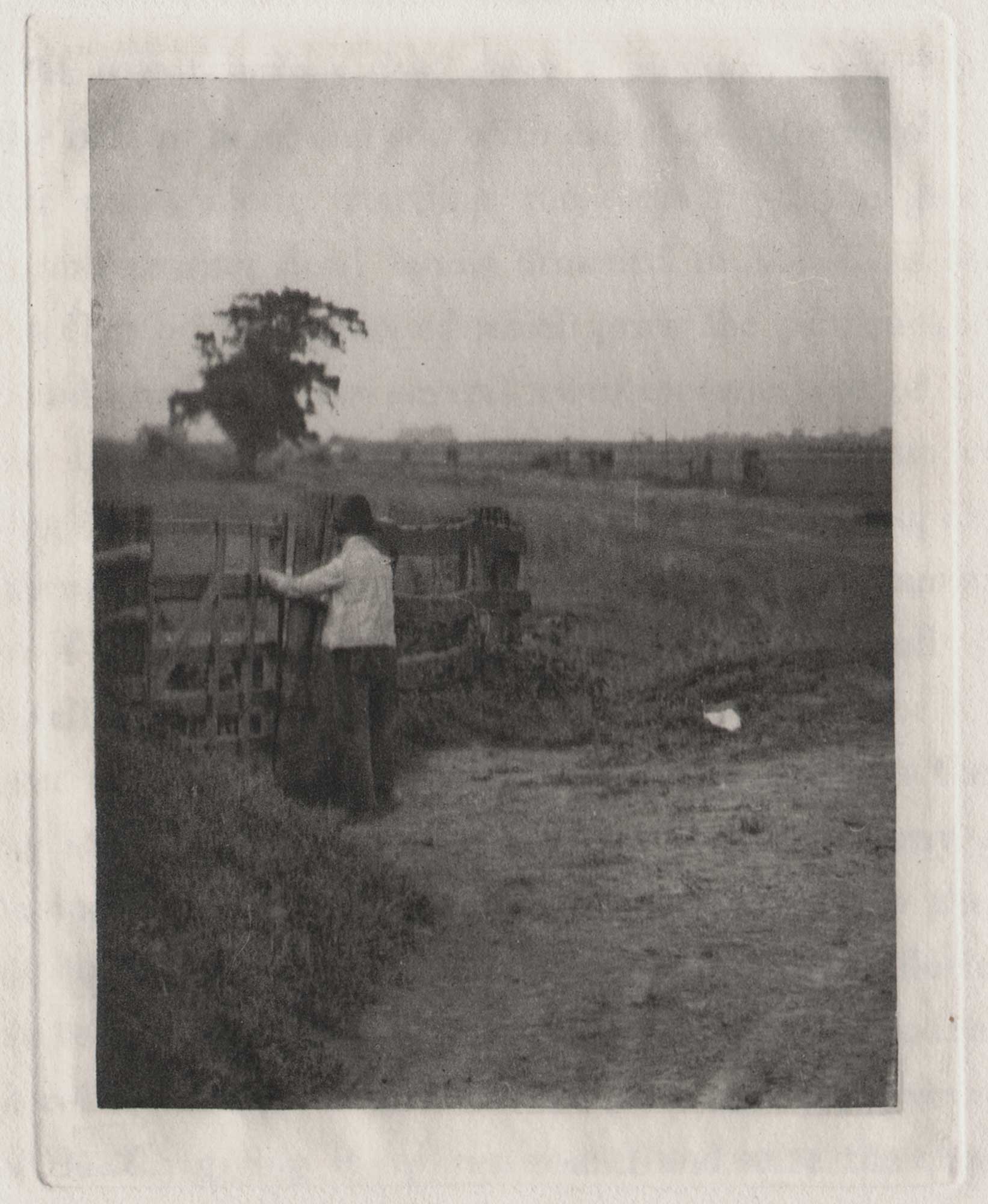

The Last Gate

A farm hand closes a gate. The final plate in Marsh Leaves, Emerson in a way has made this a literal photograph and philosophical statement. By closing a gate, the artist presents a symbolic ending to his own decade-long journey of photographic wanderings spanning his theories and practice of Naturalistic Photography. In total, his efforts created a new artistic vision for the medium itself. A double meaning? The Last Gate is cropped from one of his larger farmland scenes: “The Wealth of Marshland”, (below) also published in photogravure, from his 1887 volume Idyls of the Norfolk Broads. In essence, the repurposed image— a puzzle-piece to a larger career— validates this journey, showing those willing to revisit old favorites can find bountiful harvests, symbolic to the Broadland scenes P.H. Emerson loved so well.

Peter Henry Emerson (British, born Cuba, 1856 – 1936), photographer The Wealth of Marshland, 1887 Photogravure Plate: 14.4 × 20.5 cm (5 11/16 × 8 1/16 in.), Image: 11 × 17.6 cm (4 5/16 × 6 15/16 in.), Sheet: 33.7 × 43.3 cm (13 1/4 × 17 1/16 in.) The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 84.XB.696.1.9

Much has been written of P.H. Emerson’s final volume of masterful photographs reproduced in photogravure titled Marsh Leaves, published in 1895. The source material came from 16 earlier plates taken by the artist in 1890-91 during his one-year cruise aboard the wherry Maid of the Mist while navigating and exploring the Norfolk and Suffolk Broads. Beginning in the late 1880s and during this period he was also learning the art of photoengraving from Walter L. Colls. His 1893 volume On English Lagoons would be the first illustrated with plates etched and printed by himself, followed by these more refined and nuanced East Anglian scenes translated into delicate photogravure impressions.

“Emerson’s final photographic book Marsh Leaves was published five years after he renounced the belief in photography’s fine art status. In many ways paradoxically his most artistic volume, it is comprised of his most personal writings, only obliquely linked to his most exquisite images of pure landscape. Self-consciously composed as a conclusion for his decade in the photographic arena, it is his final statement of art and life, as well as a farewell to the private pictorial sphere that East Anglia had been to him.“—Ellen Handy: Imagining Paradise: The Richard and Ronay Menschel Library at George Eastman House, 2007. p. 193