Sir John Frederick William Herschel is someone to pay attention to when thinking about photography. And for no other reason? He is credited with coining the very word “photography” in the English language. (with apologies to French-Brazilian painter and inventor Hércules Florence)

Herschel–famed English astronomer and, for our purposes here, photographic pioneer–is one of the unsung heroes of what we know as modern photography. For those lucky enough to have worked in a wet darkroom, it was Herschel the scientist and chemist who discovered and corresponded with William Henry Fox Talbot that sodium thiosulphite, commonly known as “hypo”, could “fix” silver halides, and therefore was a reliable means of making a photograph permanent.

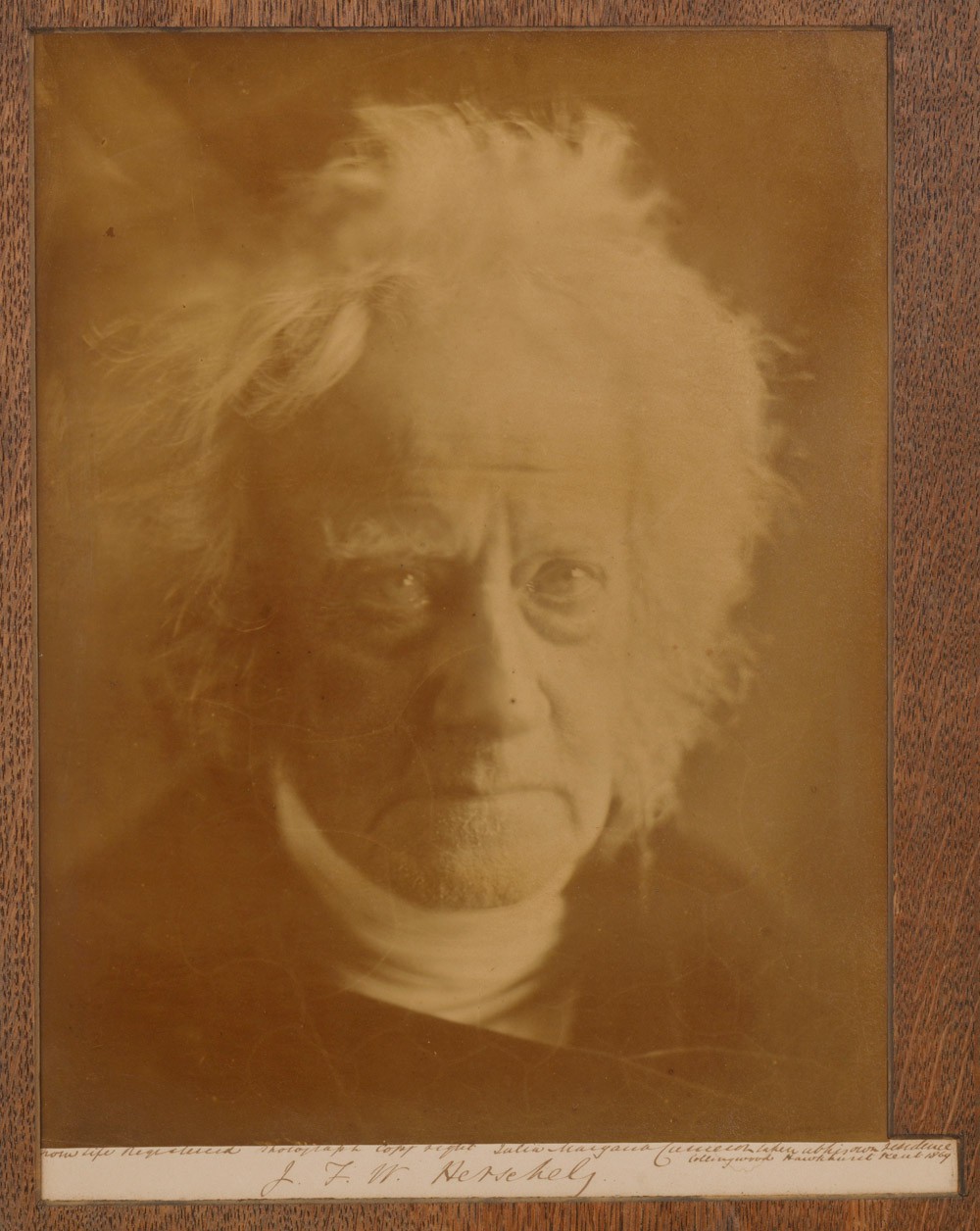

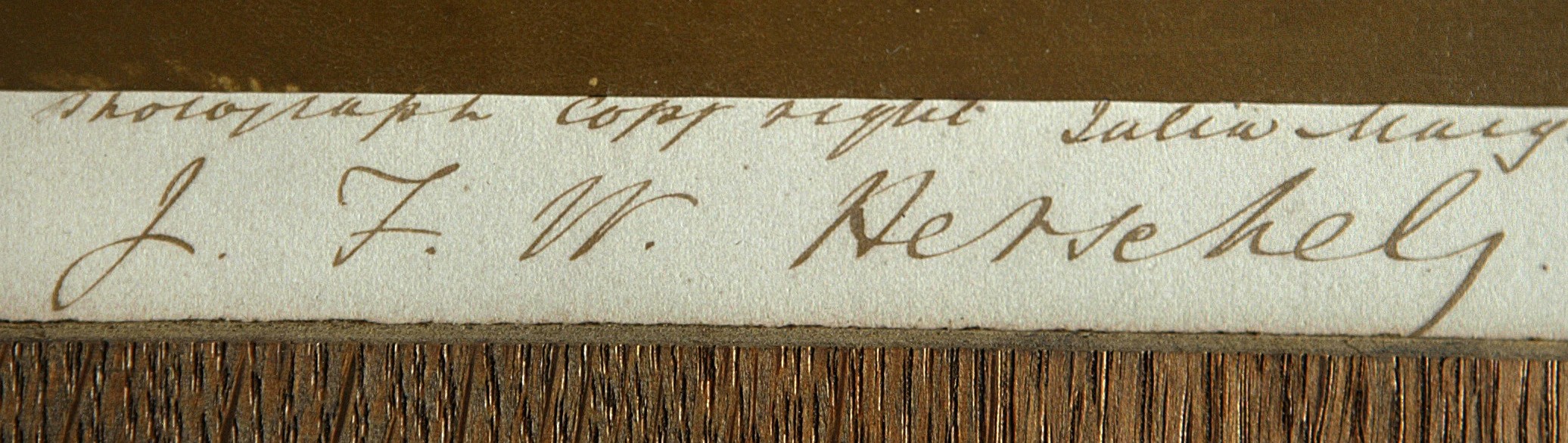

The photographic mount ink inscription reads in full left to right: “From Life Registered photograph copyright Julia Margaret Cameron taken at his own residence Collingwood Hawkhurst Kent 1867” and then signed below: J. F. W. Herschel

Buried next to Sir Isaac Newton in Westminster Abbey, Herschel’s genius was an ability to make science understandable to both the curious and the more educated through his writings and presentations to the established scientific bodies of the mid 19th century.

As a collector, I’ve always been drawn to the art of photography. However, I have an appreciation of the science that has always been the important backdrop for making modern photography possible in the first place, and Herschel’s role in that science. This wonderful photographic likeness of Herschel, taken by his dear friend Julia Margaret Cameron, has always been of interest to me as a collector because it combines both art and science.

A Cameron portrait of Herschel appeals on many photographic collecting levels. It is considered one of the great “head” portraits that Cameron was famous for-perhaps more so because of its brooding and mysterious nature; a symbolic likeness of a man whose life was spent on a quest for discovery and explanation of the unknown.

But It has never been my intention as a collector to purchase a photograph because it is considered one of the “greatest hits” in the history of the medium. On the contrary, I am continually surprised how much wonderful material is available of the unknown and unsung photographer, often for the price of a song. The beauty of collecting photography in our modern age is that its’ story has not been fully chronicled nor even discovered, and one of the aims of PhotoSeed will be to fill in some of these blanks for the record.

The four known portraits of Herschel were taken late in his life in 1867 by Cameron. Through much luck I was able to purchase this one, a mounted (with wood veneer overlay) albumen example at auction in 2004 from a gentleman who originally purchased it at auction in Dublin, Ireland in 2003.

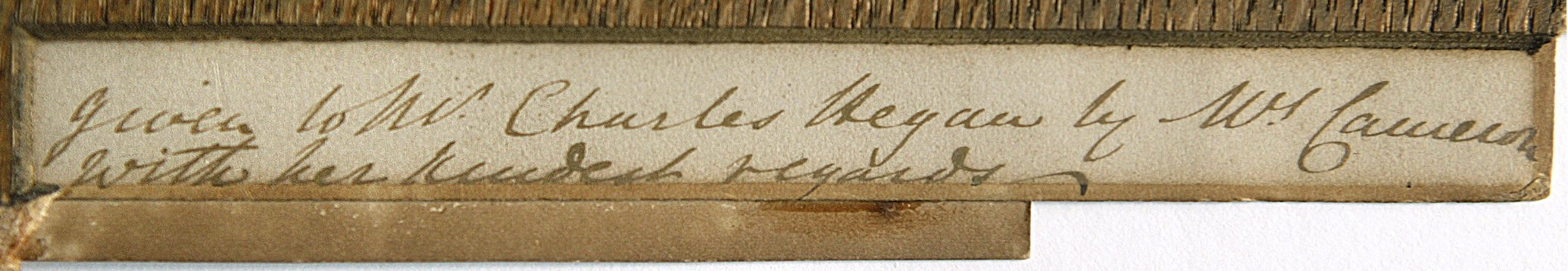

Twice personally signed by Cameron, the bottom right hand corner of the mount provides the following inscription by her: “Given to Mr. Charles Hegan by Mrs. Cameron with her kindest regards.”

Naturally, I was intrigued as to the mysterious Mr. Hegan was and how he might have known Cameron. Through research, I tracked down the family who originally consigned the Herschel portrait as well as other items to the Irish auction. And this is why photographic sleuthing pays off. It turns out that in 1899 this photograph was a wedding present from Hegan to one Joseph Alfred Hardcastle. (born 1868) Never heard of him? It turns out he was Herschel’s grandson, and the photograph had stayed in Hardcastle’s family until 2003. A very nice provenance indeed.

A friend of a member of the present-day Hardcastle family in Ireland did research on my behalf, trying to figure out who Hegan was and his possible connection to Cameron, but came up empty. Later, my own research determined Hegan (Charles John Hegan) was a fellow of London’s Royal Geographical Society (elected 1873) who likely knew Hardcastle through scientific and perhaps family connections (they both attended Harrow but over 20 years apart). Ownership of the Herschel portrait makes complete sense as both Hegan and Hardcastle were devoted to scientific endeavors. On this front, Hegan travelled to South America to conduct fluvial research on behalf of the Royal Geographical Society and Hardcastle, a fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society who lectured and conducted research relating to astronomy, was appointed director of the Armagh Observatory in Northern Ireland, but died suddenly in 1917 while in route there.

So talk about the perfect wedding gift. Hardcastle’s love was astronomy. Although only three years old when his grandfather was buried next to Newton, Herschel would have been proud of a grandson following in his own esteemed footsteps.

The photograph is signed boldly (believed to be in Cameron’s hand) : J. F. W. Herschel

There are pencil notations by a framer most likely done after the 1899 wedding, including “Show all writing” on the back of the original Cameron mounting board. Visible as well and centered at foot of mount is a verso impression of a Colnaghi blindstamp, indicating the photograph was once marketed by Cameron through the well-known London gallery. Somehow, the print made its’ way back to Cameron and she personally signed and presented it to Hegan at an unknown date: “given to Mr. Charles Hegan by Mrs. Cameron with her kindest regards.”