Sigismund Blumann, (1872-1956) an American who became an important editor and photographer after moving to San Francisco, California from New York City in the early 1880’s is our subject for this post, along with his involvement with and history of Camera Craft magazine. Never heard of him? A few relevant but by no means comprehensive list of details about this gentleman whose friends addressed him as “Sig” for short:

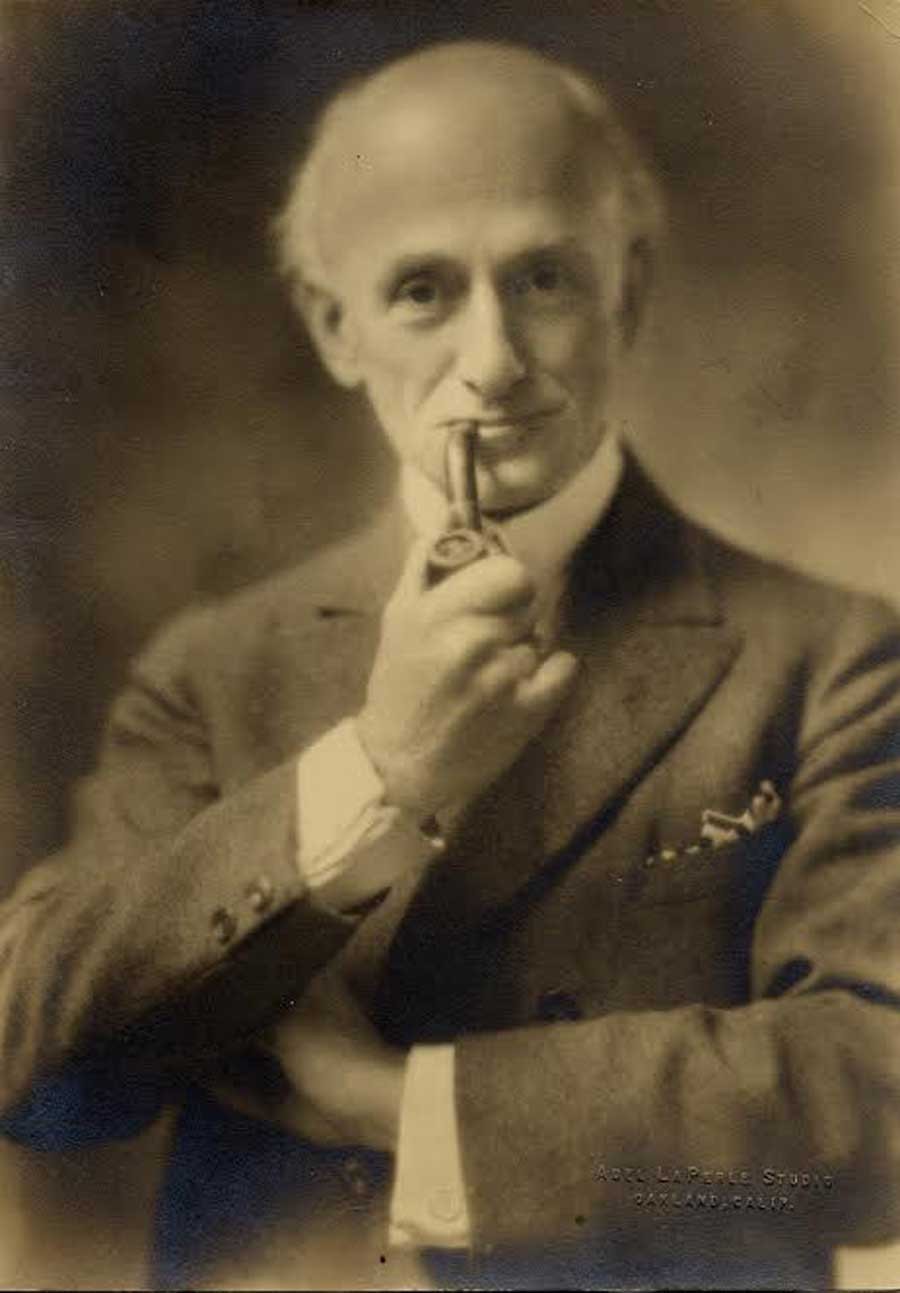

Detail: “Self-Portrait of Sigismund Blumann” (1872-1956) : American: gelatin silver print ca. 1930: Blumann was editor-in-chief of San Francisco-based Camera Craft magazine from 1924-1933: Photograph courtesy Thomas High

West Coast champion for photography in his role as Editor-in-Chief of Camera Craft magazine from 1924-1933. Prolific writer for said journal whose love of language sometimes lead to his mangling of it, but only with the best of intentions.

Significant pictorialist photographer from the same period and earlier whose darkroom work was equally inventive and important.

Poet.

So gregarious in affect, photographic historian Christian A. Peterson duly notes, (1.) that as editor, he personally answered all correspondence sent to him by his 8000 monthly Camera Craft readers in addition to his regular duties of penning multiple articles for each issue.

Possession of a sly sense of humor: look no further than a ca. 1930 self-portrait in which his suit lapel sprouts a long cable release rather than a floral boutonnière.

Conservative writer in print who often took a while to accept new ideas: as one example, Peterson notes his use of the made-up word “Sewereelism” included in a 1938 editorial written by him on his feelings towards the failings of the art movements Surrealism and Dada for the magazine Photo Art Monthly, a publication he owned himself. (2.)

Pipe smoker extraordinaire. Featured not only in the above referenced self-portrait but immortalized by artist W.R. Potter in print every month as artistic caricature shown smoking and reading a book used for his Under the Editor’s Lamp column in Camera Craft beginning in April 1926.

Detail: Cover Design: Camera Craft magazine: June, 1900: William Howell Bull: 1851-1940: American-California: 26.0 x 17.5 cm: two-color wood engraving : Sunset Press & Photo Engraving Company – San Francisco: cover price at upper right corner 15¢. Although this was the second issue of the magazine to appear, the first issue for May used the same cover design showing this stylish woman done in the Art-Nouveau style with small box camera slung on her side. From: PhotoSeed Archive

Detail: “Everyone Reads It”: Mrs. C.S. Smith, American: Marysville (CA): halftone from June, 1900 Camera Craft magazine p. 57: 10.6 x 8.1 cm: A young girl holds up the very first issue of Camera Craft dated May, 1900. The design by California artist W.H. Bull was also used as the cover for June, 1900. From: PhotoSeed Archive

Sigismund Blumann: Short Biography

For the past three years, I’ve had the distinct pleasure of corresponding with Thomas High, Sigismund Blumann’s grandson, and been equally fortunate in acquiring a small archive of Sig’s vintage work for PhotoSeed previously kept in the family. Unlike Sig’s friends, Tom tells me, as a boy of perhaps five or six, he would of course address him as Grampa Blumann. Tom goes on to say:

“I only wish I had known him better – he died when I was a child, and my only real memories of him were playing rummy and whist with him.”

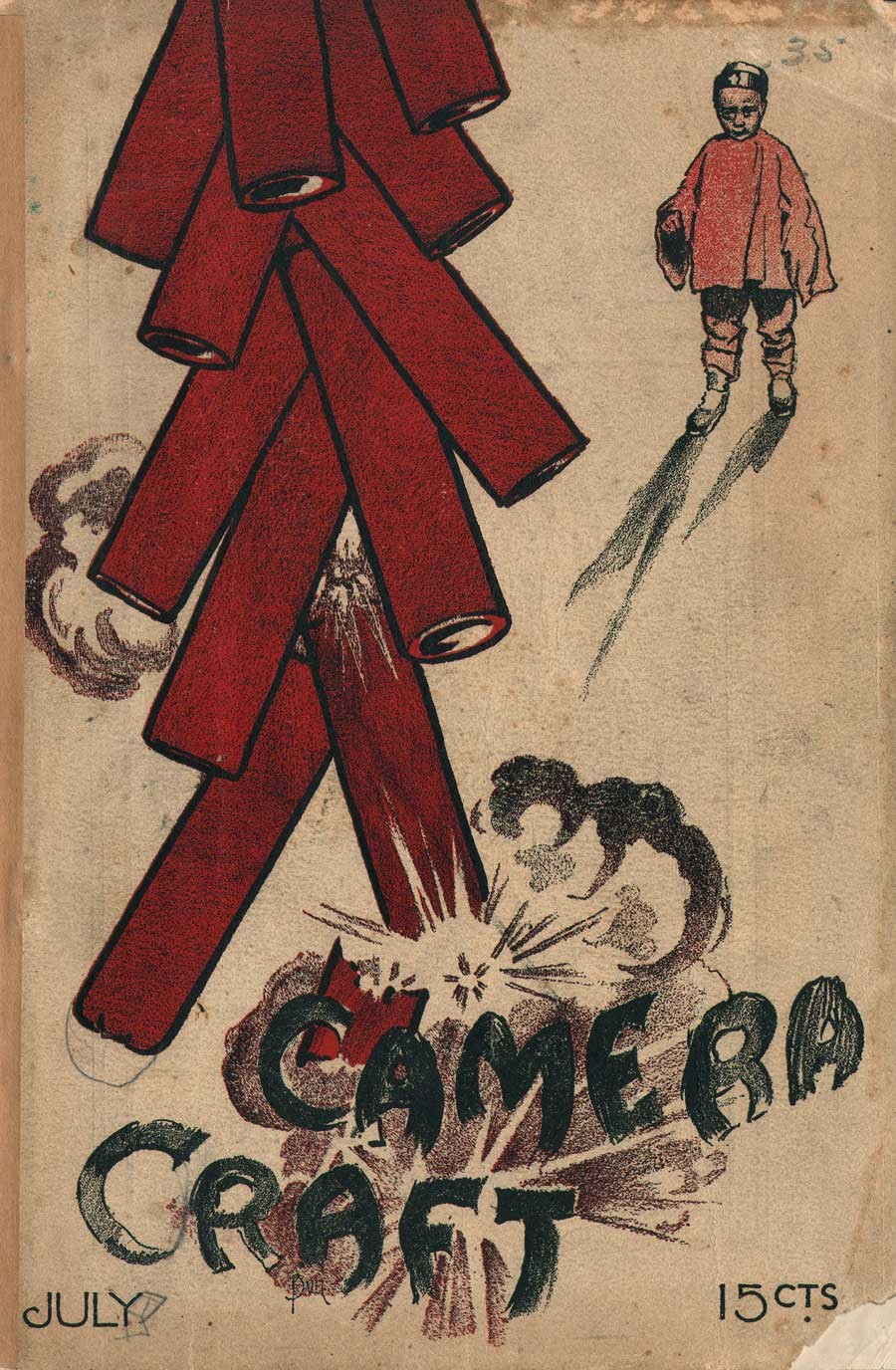

Cover Design: Chinese Firecrackers: Camera Craft magazine: July, 1900: William Howell Bull: 1851-1940: American-California: 26.0 x 17.5 cm: two-color wood engraving : Sunset Press & Photo Engraving Company – San Francisco: cover price at lower right corner 15¢. From: PhotoSeed Archive

Tom has also agreed to let me reprint for purposes of introduction the following short biography of his grandfather written in October, 2009, for which I’m very grateful.

Sigismund Blumann (1872-1956) by Thomas High

Sigismund Blumann was born on September 13, 1872, in New York City, the son of Alexander Blumann and Rosalie (Price) Blumann. He came to San Francisco with his parents in late 1881 or 1882, and subsequently became a professional pianist and music teacher.

Sigismund Blumann married first on August 30, 1894, to Adele Morgenstern. They divorced in May of 1895. He married second on June 4, 1901, to Hilda Axelina Johansson and they subsequently had four daughters, Ethel, Amy, Lorna, and Vera.

In the 1890s, Sigismund Blumann became interested in photography and had begun taking photos seriously by 1900 while living in San Francisco. At the time of the San Francisco earthquake on April 9, 1906, he and his wife were still living with his parents on Army Street. He volunteered to help the recovery and, with his official permits, got through the lines and took a number of photographs.

Mr. Blumann was also a prolific writer and he authored numerous articles, commentaries, and poems.

After the 1906 earthquake, the Blumanns moved to Davis Street in Fruitvale (later part of Oakland). From that time, all of his photographic work was done in his darkroom at the Davis Street home.

Photography increased in importance in his life, and at the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition he combined all of his talents: he played in an orchestra, photographed the Fair, and worked as a correspondent for the New York Tribune and other newspapers.

In the early 1920s, Sigismund retired from an active career in music and entered the profession of efficiency engineering, with offices in the Monadnock Building in San Francisco. His principal client was the Forster Music Publishing Company.

He continued his interest in photography and in 1924 he became editor of Camera Craft magazine. In addition to editing the publication and writing numerous articles for it, he also wrote the Photographic Workroom Handbook, published by Camera Craft in 1927.

Mr. Blumann’s last issue as editor of Camera Craft was in August of 1933. Several months later, he launched his own magazine, Photo Art Monthly, which he edited and published until 1940. During this period, he also produced several more manuals for amateur photographers, including the Photographic Handbook, Photographic Greetings – How to Make Them, Enlarging Manual, and Toning Processes.

In 1940, he sold the Photo Art Monthly to his assistant, Franke Unger (who married photographer Adolf Fassbender about the same time). She soon closed the magazine.

The Blumanns continued to live at their Davis Street home for the rest of their lives, joined by their unmarried daughters, Ethel and Lorna Blumann, both librarians. He produced little photographic work in the 1940s and 1950s, contenting himself to dabble in photography and discuss it with his new son-in-law, William A. High, who married his daughter, Vera, in February of 1943. Bill High was a commercial photographer before World War II, a combat photographer for the US Army during the war, and the founder of the photography department at Oakland’s Laney Trade School (later Peralta Junior College) thereafter.

Sigismund Blumann died in Oakland on July 9, 1956, and Hilda Blumann died on February 1, 1958, also in Oakland.

Sigismund Blumann’s photos are in the Oakland Museum, Minneapolis Institute of Art, High Museum in Atlanta, and elsewhere.

For further information, see “Sigismund Blumann, California Editor and Photographer,” by Christian A. Peterson, in History of Photography, vol. 26, no. 1. (Spring 2002).

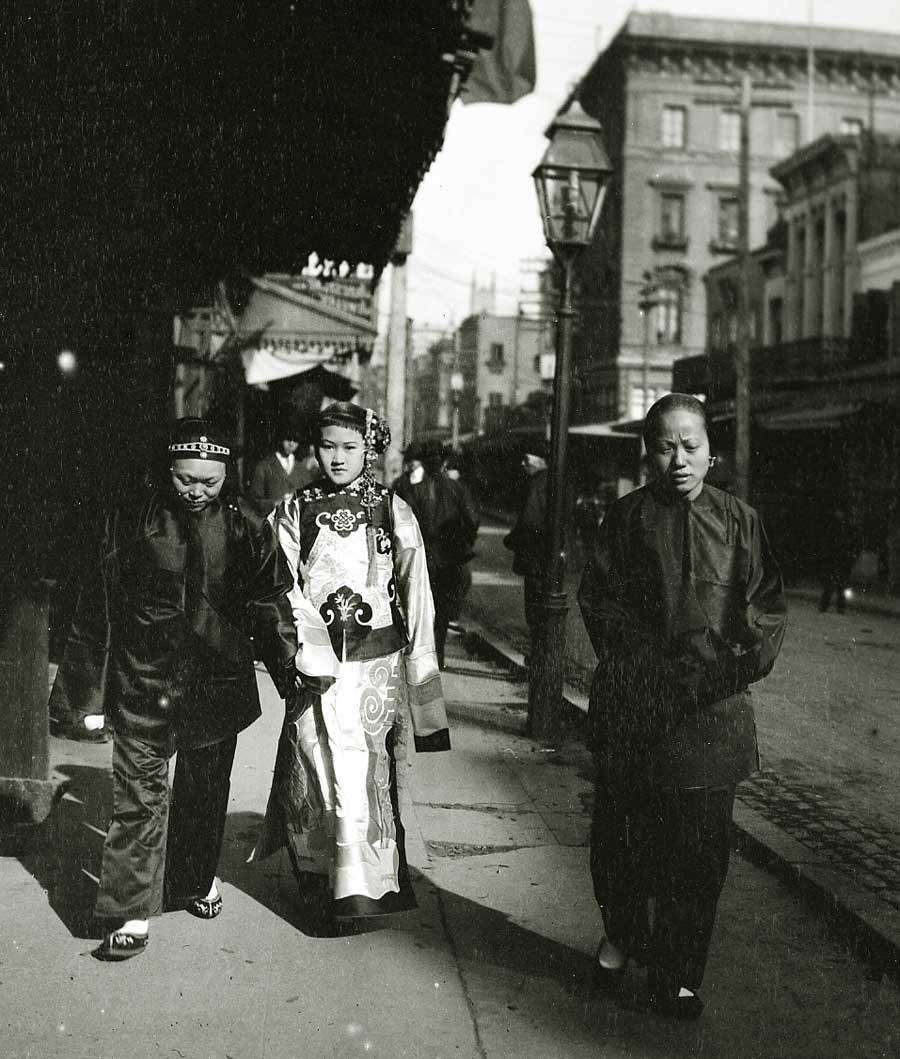

Detail: “Highborn Lady With Duenna”: Sigismund Blumann: American: ca. 1901: This view is from a collection of at least 43 documentary photographs, with several corresponding paper negative envelopes dated 1901 by Blumann donated by his family to the California Historical Society. They can be viewed there as part of the collection “The Chinese in California: 1850-1925.” Photograph courtesy Thomas High

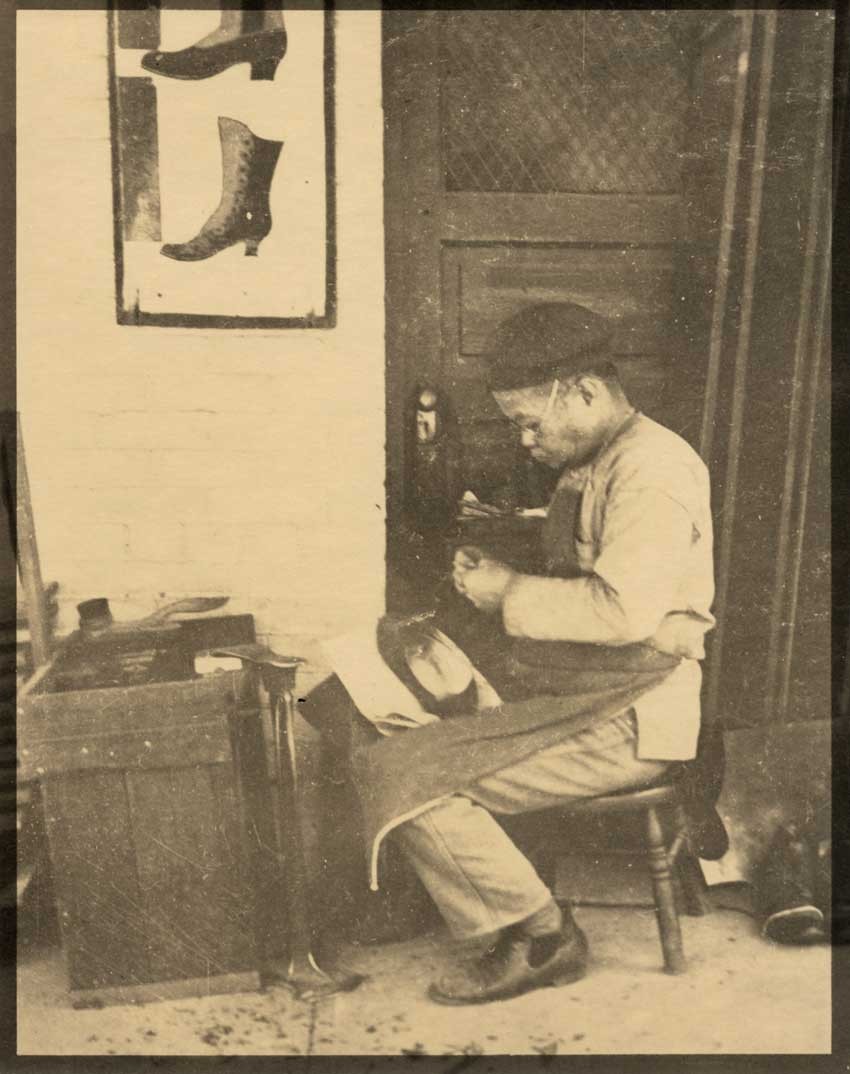

“Chinese Cobbler”: San Francisco Chinatown: Sigismund Blumann: American: ca. 1901, printed early 1920s: gelatin silver print- app. 8 7/8 x 7.0″: variant: “Shoe Mender”: from California Historical Society collection: FN-34374: Photograph courtesy Thomas High

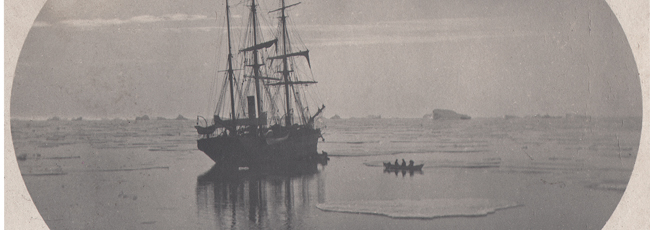

Detail: “Ruins” (San Francisco Earthquake): Sigismund Blumann: American: ca. 1906: gelatin silver print: 13.0 x 18.0 cm: overprinted with Blumann’s winged griffin monogram at lower right: Photograph courtesy: California Historical Society: The 1906 San Francisco Earthquake and Fire Digital Collection: Local Call # FN-33293

“Day Dreams” : Charles Rollins Tucker 1868-1956: American: gelatin silver print: June, 1906 printed 1915: 27.3 x 20.4 | 43.2 x 35.5 cm : First titled “Study in Home Portraiture” and published full page in the Oct. 1906 Photographic Times, this interior study later appeared as a full-page halftone in the July, 1907 Camera Craft magazine, and is a representative example of the pictorialist work that regularly appeared in its pages. Coincidentally, imagery like this was also gaining popularity during this time among amateur and professional photographers, and Sigismund Blumann was no exception, teaming up with fellow photographer Jacques Tillmany in 1907 on a part-time basis offering in-home photographic portraiture. From: PhotoSeed Archive

Beginnings in Word and Photography

Writing under his infrequent pen name Charles H. Fitzpatrick in Camera Craft in 1925, (3.) Sig most likely gives us a small hint of his own beginnings in photography, a passion that would soon evolve into his extensive documentation of life of San Francisco’s bustling Chinatown neighborhood in 1901. (4.) Later in this capacity as street shooter, he played the role of documentarian in the aftermath of the destruction of San Francisco in the 1906 earthquake and subsequent job as part-time portrait photographer after relocating to neighboring Oakland in 1907 due to the destruction. (5.) all while making his living as musical performer and teacher) :

Having become interested in Photography back in 1900 as an amateur with an old style Adlake plate camera, and two years later as a professional with a studio— and almost continuously since in Commercial Photography the author has had a wonderful opportunity to study composition both by experience and observation of the work of others. (6.)

Cover Design: Camera Craft magazine: San Francisco, CA: July, 1922: 26.5 x 17.5 cm: two-color wood engraving : unknown artist and printer: cover price at upper right corner 15¢. This uncredited Camera Craft cover design first debuted with the January 1913 issue and featured a simple design of a plate camera shown in profile(lens board on right side) with dark cloth draped at center and bulb shutter release cable hanging down. This design lasted through the June, 1923 issue and was replaced with illustrations of architectural landmarks, notable western scenery and other thematic drawings done by San Francisco artist W.R. Potter through the September, 1924 issue. From: PhotoSeed Archive

It was sometime in the 1890s, photographic historian Christian A. Peterson notes, that he “first used his wife’s Kodak camera to make snapshots and soon began searching the photographic periodicals for information and advice.” (7.) His editorship of Camera Craft as momentous professional occasion aside, Sig’s immersion in all things Photographic may very well have reached a high-point by 1933, the year he became a charter member of the Photographic Society of America as well as being honored a Fellow of the Royal Photographic Society.

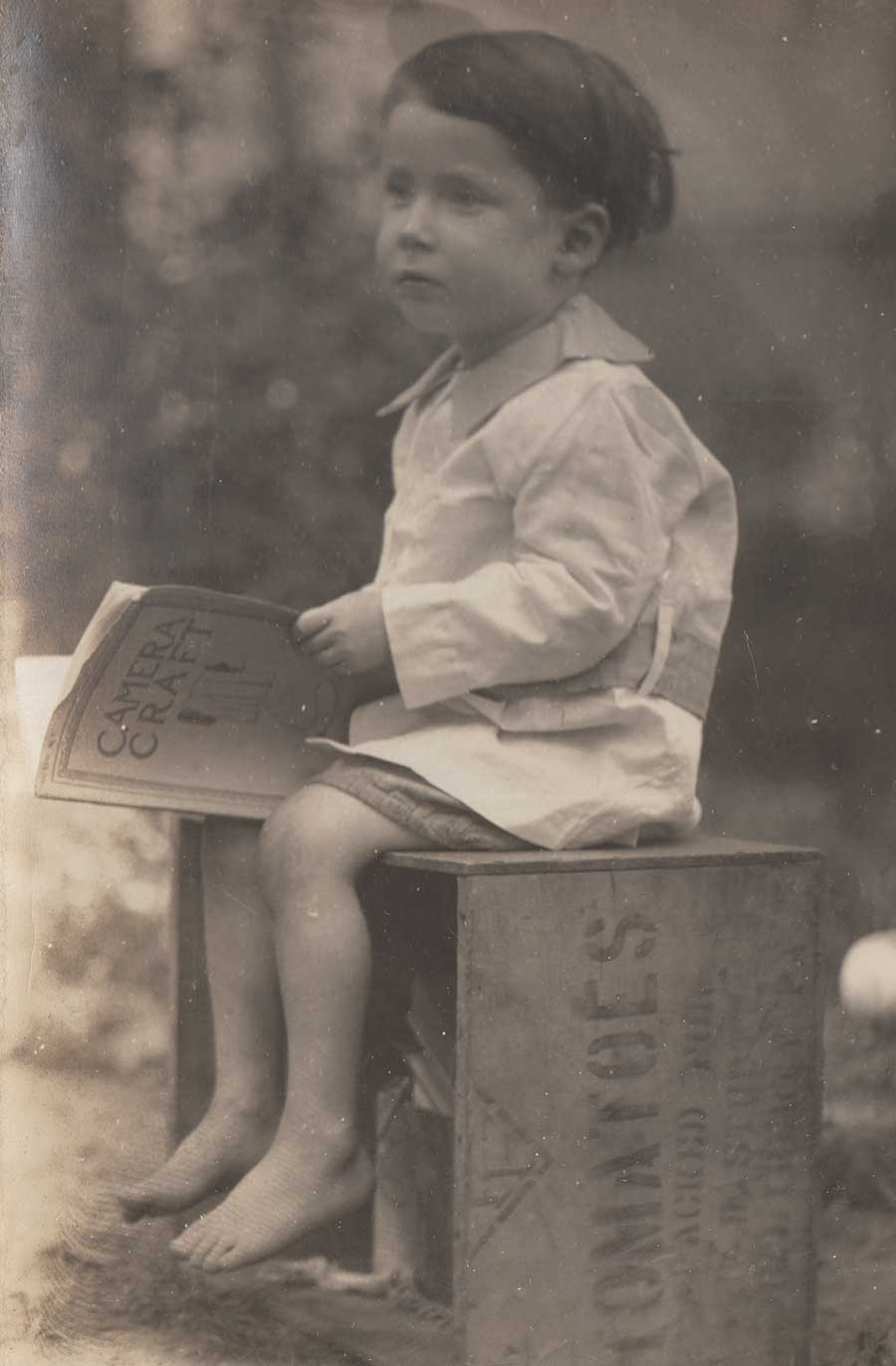

Detail: “Child Sitting on Tomato Crate Holding Camera Craft Magazine”: by anonymous American photographer printed as unmailed postcard: gelatin silver print ca. 1920-25: 11.6 x 8.8 | 13.8 x 8.8 cm: written in graphite on verso: “with Love. Ellsworth” with the name “Walter” opposite address field. Child sits on crate stenciled on side as being from Pennsylvania-indicated “Packed For….PA ” on side, with photo purchased from Parma, MI collector. From: PhotoSeed Archive

Photography in itself however was not his only reason for being during his professional career as editor, and even earlier as a musician. This was because Sig was a romantic at heart, a dreamer who had a great fondness for language, and the will to commit it to paper. Starting out for example, only in his early 20’s, he composed the following poem for the April, 1895 issue of the California-based magazine Overland Monthly:

PLEASURE.

PLEASURE is like perfect liquor,

Sweet to taste and after taste,

And like, too, in that when gotten

We imbibe too much, then waste,

And we find when pleasure passes

Life is empty as the glasses.

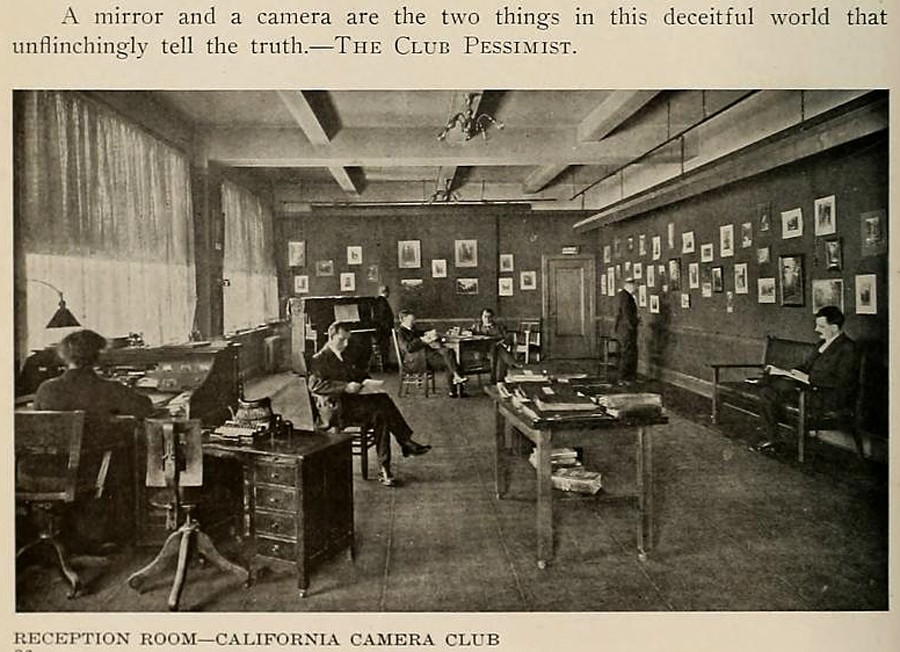

“Reception Room— California Camera Club”: 1914: taken by an unknown photographer, this image appeared as a halftone illustration in the February, 1914 issue of Camera Craft for a story on the club, founded in 1890. At the time this appeared the club was located at 833 Market Street in San Francisco. The scene shows members seated with an exhibit of photographs on display at rear and on wall at right. Camera Craft regularly featured news of this important club, and future editor of the magazine Sigismund Blumann, although not a member, attended and was an occasional speaker. Photographic historian Christian A. Peterson notes Blumann spoke at this club in 1916 and much later, between 1934-40 attended gatherings here as well as at the Leica Club of Oakland, East Bay Camera Club, Golden Gate Miniature Camera Club, Photographic Society of San Francisco, San Jose Camera Club, and Western Amateur Camera Conclave. From: California State Library: Archive.org

Detail: “Up the Path”: Chester Moulton Whitney: American, b. 1873: 1914 or earlier: gelatin silver print: 24.8 x 19.3 cm: This photograph was illustrated as a full-page halftone with printed ornamental Art-Nouveau frame border in the August, 1914 Camera Craft, p. 422, and is a representative example of the pictorialist work that regularly appeared in its pages. From: PhotoSeed Archive

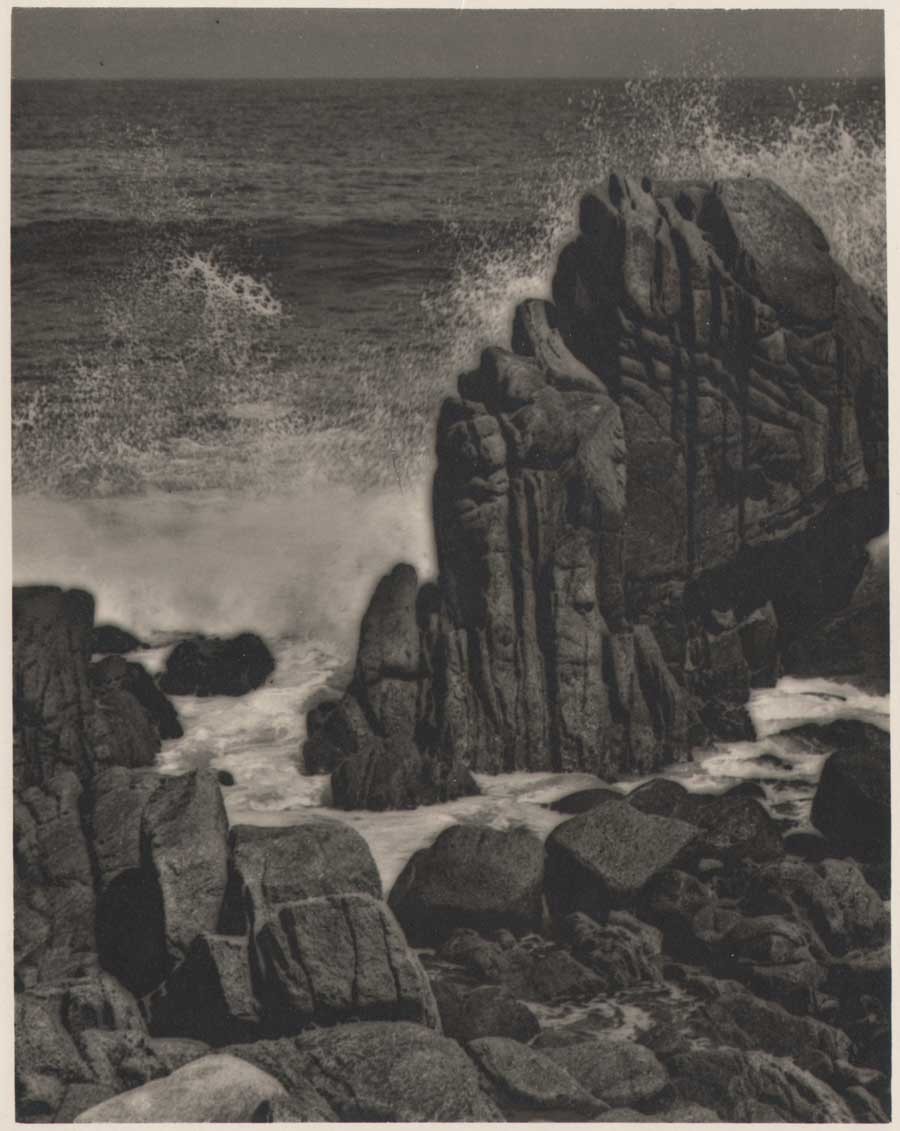

Wearing the hat of Poet-in-Residence at Camera Craft, Sig never neglected this early love of poetry for the publication, often combining his own photographic efforts alongside original compositions. One example, which he titled Lugubrio, though technically not even a real word, appeared in April, 1927, and was his way of simply assigning a mournful, or lugubrious meaning to his own photograph depicting jagged rocks and crashing waves-seen in his dramatic coastal landscape most likely taken on the Pacific coast:

LUGUBRIO

By Sigismund Blumann

The drowned and dead, now turned to stone,

Stand watching by the shore

And you may hear them through the night,

From set of sun to morning light,

As they shall do for evermore,

Weep as they watch, and moan. (p. 177)

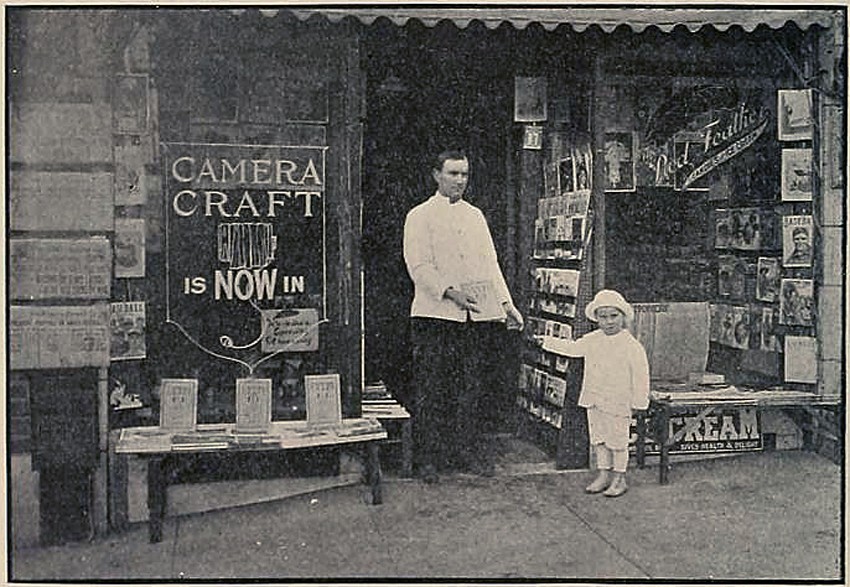

“Camera Craft is Now In”: 1914: taken by an unknown photographer and used as a form of soft advertising, this image appeared as a halftone illustration in the June, 1917 issue of Camera Craft. It shows San Francisco business owner J.F. Brandert, owner of the Red Feather Store at 435 Jones Street, handing off a copy of the journal to a young visitor, with a display of three issues propped up on a bench at left in front of a window lettered with a graphic of the journal’s cover: “CAMERA CRAFT IS NOW IN”. From: California State Library: Archive.org

“When From Behind the Moondipt Bush Titania Floated in a Silver Haze”: 1917 or before: Sigismund Blumann, American: This photograph was used as the frontis halftone for the July, 1917 issue of Camera Craft helping to illustrate the article “Poetry and Photography” written by Blumann. The photo shows Vera Hahn, a childhood friend of his eldest daughter Ethel Blumann. (b. 1902) He said of the photo: “She was costumed for a pageant and we all wanted a memento of the charming vision she made in our garden, among the green plants.” This early example of Blumann’s work also included one of his original poems titled “To Childhood”: the first stanza: “Oh blessed youth! When from the enchanted page | Fancy stepped forth and made the unreal real, | When from behind the moondipt bush | Titania floated in a silver haze and greeted me! From: California State Library: Archive.org

Camera Craft: Western Photographic Journal

Although he’d been a contributor to its’ pages in words and photos after the first decade of being founded, it would be 24 years from the journal’s 1900 founding until Sig would begin to establish an enduring legacy in the history of photography via his role as Editor-in-Chief of Camera Craft. Some historical background on the intents and purposes for this ground-breaking publication are in order.

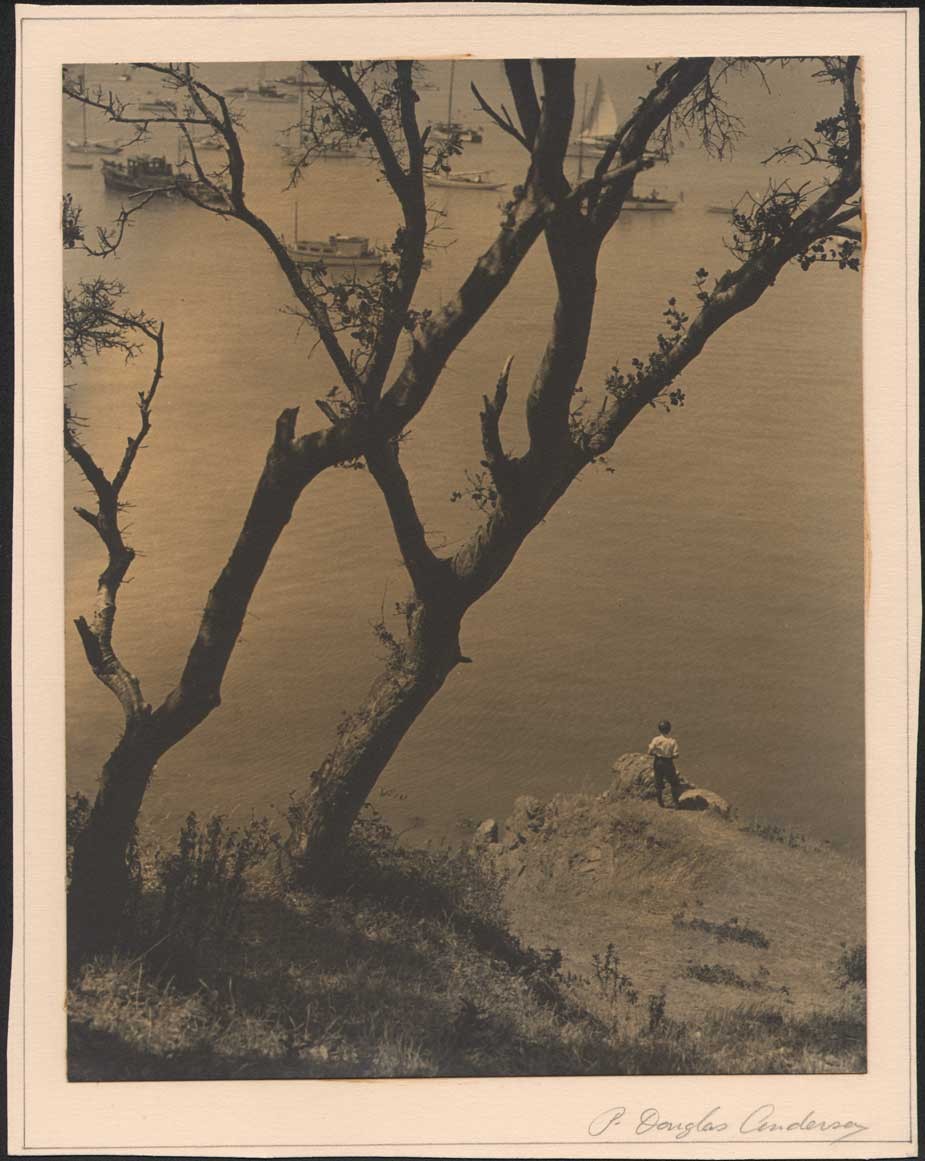

“Boy Looking out onto Bay” (San Francisco?-title supplied by this archive): ca. 1920-25: Paul Douglas Anderson, American 1887-1964: toned bromide or gelatin silver print: 24.2 x 19.0 | 27.5 x 21.6 cm: P. Douglas Anderson was an associate editor of Camera Craft beginning in May, 1923 & became editor-in-chief by January, 1924, continuing through the July issue. He was replaced by Sigismund Blumann the following month. Active in photography between 1910-1940’s, Anderson was a member of the Camera Pictorialists of Los Angeles and Pictorial Photographers of America. From: PhotoSeed Archive

First based in San Francisco at 120 Sutter Street and issued monthly by the Camera Craft Publishing Company under the direction of editor W.G. Woods, the photographic journal Camera Craft was founded on the principles the West Coast of the United States should have an equal geographical mouthpiece of influence to counter that of the East Coast in promoting photography-for both professional and amateur workers. (to this end a separate page was devoted monthly to the happenings of many California amateur clubs) For the first issue of May, 1900, the following observations and arguments were made by the journal in support of these ideals:

The growth of photography, the introduction of simplifying methods in scientific picture-making, during the past twenty-five years is one of the wonders of the century. The phenomenal strides made by the photographic inventors of the world, resulting in the production of simple devices and convenient appliances, have made photography in all of its branches an almost universal fad. The Pacific Coast, ever ready to appreciate the merits of an innovation, has kept well abreast in the steady march of progress.

The wonderful climate of California lends itself enthusiastically to the wants of the photographer. The hand of Nature has reared, in eternal beauty, scenic effects unequaled elsewhere on earth. The very atmosphere of the Far West encourages the artistic impulse of its people. With such great natural advantages it is small wonder that when the western photographer has seen fit to cross the continent to compete with the eastern brotherhood he returns with laurels upon his brow. Not less wonderful is the existence of the largest Camera Club in the world in the city of the Golden Gate.

Yet, strange as it may seem, this great class of enthusiasts, this immense body of earnest workers has never been represented by a publication worthy of its trust. The photographers of the West have for years depended upon the journals of the East for enlightenment, but have looked in vain for recognition in their columns. It is to remedy this condition that Camera Craft now makes its bow to the public.

As to the scope of Camera Craft nothing can be said; it will have to speak for itself. The only promise made is the sincere intent on the part of the publishers to improve with each succeeding issue. The one hope of the magazine is that it may be so conducted as to meet the approbation of its readers and lend its aid to the material welfare of all interested in photography, whether for pleasure or for profit. (p. 26)

This triptych shows the three different Camera Craft magazine columns editor-in-chief Sigismund Blumann was involved with during his tenure at the journal from 1924-1933. “Under The Editor’s Lamp” at top featured a caricature of the editor puffing a way on his trusty pipe while “Chit Chat About our Friends” at middle is comically subtitled “Ye Editor Retaileth Newes of Ye Profession And In Quaint Italics Titillateth Ye Sphynx With Hys Quill”. “The Amateur And His Troubles”, “conducted”, appropriately enough by the man who had once made his living as a musician and orchestra leader, who already a feature of the publication when Blumann took over. From: PhotoSeed Archive

Cover Design: Camera Craft magazine: San Francisco, CA: January, 1926: Press of the Hansen Company, San Francisco: 26.5 x 17.5 cm: two-color wood engraved border design with inset halftone photograph: “Love Me, Love My Dog” by Madam Del Oro: American? 13.3 x 12.1 cm : cover price at upper right corner 15¢. One of the journal’s seemingly obvious decisions, at least for the time, was to feature an actual photograph as a cover illustration for Camera Craft. Editor Blumann made this decision beginning with the October, 1924 issue. From: PhotoSeed Archive

With its second issue for June, ambitions quickly shifted in support of the establishment of a West-Coast professional organization:

“Camera Craft intends to agitate the question of a Pacific Coast Convention of photographers. General inquiry throughout the state has led to the belief that such a convention is not only desirable but an actual need to those who make their living through the lens and shutter.” …We recall instances where photographers of this coast have attended conventions in the East and have returned with easy honors. Camera Craft would be pleased to learn of a serious consideration of the idea. A convention held in San Francisco with a first-class salon as an adjunct would undoubtedly lead to a permanent organization, and result in the advancement of the craft in a manner hitherto untried.” (p. 68)

“Portrait of Sigismund Blumann”: ca. 1928: Adel LaPerle Studio, Oakland, CA: gelatin silver print: Blumann was editor-in-chief of San Francisco-based Camera Craft magazine from 1924-1933: Photograph courtesy Thomas High

Although preceded geographically and in scope by the Pacific Coast Photographer, a short-lived monthly established in 1892 and believed to have ceased publication several years later, Camera Craft thrived as a robust Western photographic journal for the next 41 years. It first accomplished this under the capable tenure of editor Fayette J. Clute in the early decades of the publication before Sig took over in 1924, and was carried forward by him and others until the economic and human realities of World War II forced it’s hand. This occurred after the March, 1942 issue, when Camera Craft ironically headed back East so to speak, when it was absorbed by the Boston-based American Photography magazine. An editorial appearing in the final issue stated the decision to cease publishing was made because editor George Allen Young was taking his place in the armed services among other realities.

“Japonica” : Sigismund Blumann, American: ca 1920-40. gelatin silver print: 17.2 x 22.3 cm : This is a fine example of Blumann’s pictorialist landscape work showing sand dunes and scrub trees, and was most likely taken on the West coast of the United States. Variants of this photograph have been similarly titled by the artist “Dune Pattern” and “Japanesque”. This example signed in stylized Japanese initials at lower right corner: “SB”. Three variants held by Minneapolis Institute of Arts: Accession #s: 99.230. (13-15) : From: PhotoSeed Archive

Sig As Camera Craft Editor: 1924-33

Photographic historian Christian A. Peterson, who called Camera Craft “the leading West Coast photographic monthly” and whose in-depth reassessment of Sigismund Blumann’s life and career was cited at the conclusion of Tom High’s short biography of his grandfather, called Sigismund Blumann:

“a prominent tastemaker in Californian photography during the 1920s and 1930s“. (8.)

Having an audience of 8000 monthly Camera Craft readers after coming aboard as chief editor in 1924 was surely a great start to becoming a tastemaker, but Sig proved his worth during the following nine years for his ability to impart to readers the essential knowledge of the ever-changing progress of photography. This took place in conjunction with his maintaining the vision of remaining true to himself-no matter how quirky some of his readers undoubtedly perceived him- while unashamedly promoting photographic talent in the pages of the magazine where he saw fit.

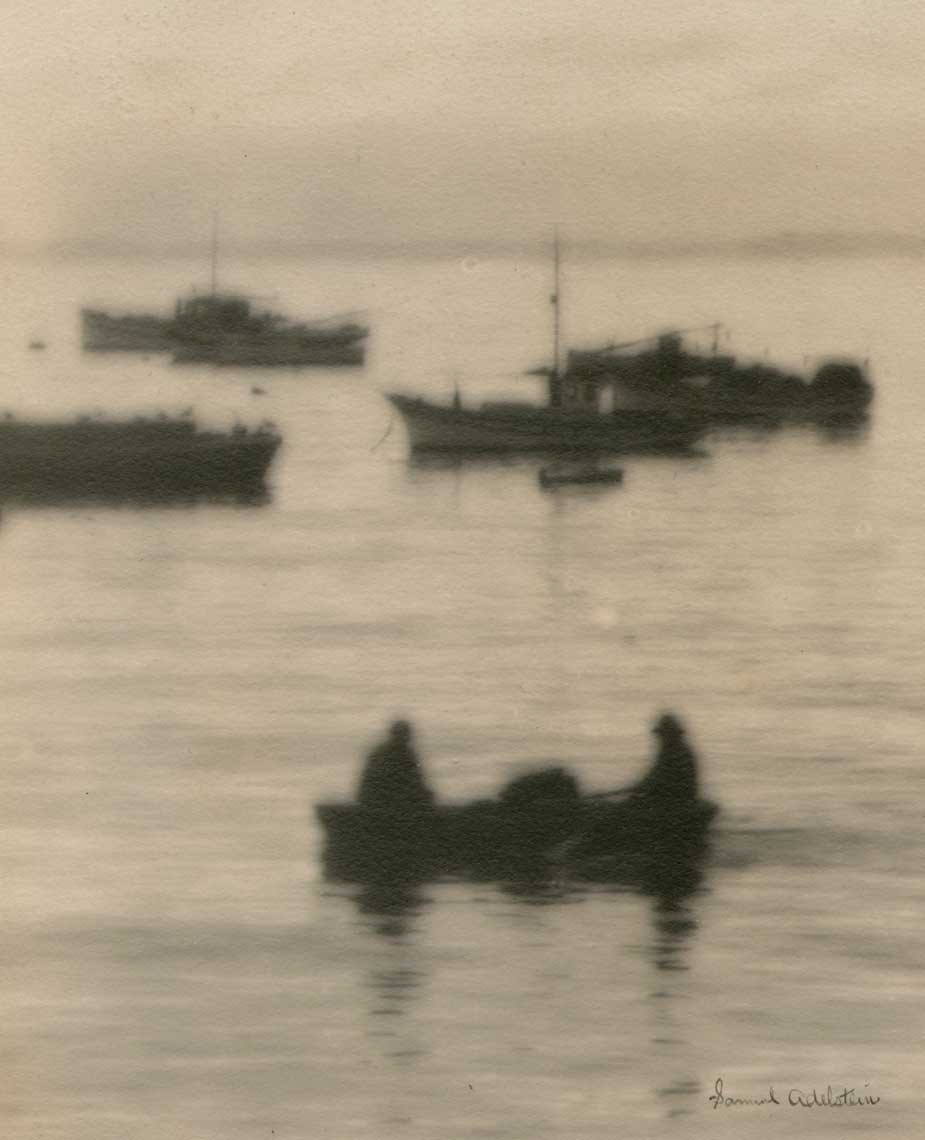

Detail: “Fishing Boats at Anchor” (probably Monterey Bay, CA) Samuel Adelstein, American, California: b. 1866?-d. 1934: silver bromide print ca. 1920-25: 18.5 x 13.6 | 40.6 x 25.4 cm: Adelstein was an active member of the California Camera Club whose pictorial works including a series of nude studies were published in Camera Craft in January, 1918 as part of the article: “An Enthusiast’s Experience”. The year before, the journal stated he was “an enthusiastic amateur photographer, a native son, a Director of the California Camera Club, and one of the Board of Governors of the Civic League of Improvement Clubs and Associations”: Immersing himself in the art of photography around 1916, he specialized in making enlargements (from sharp negatives) with a soft-focus Verito lens. From: PhotoSeed Archive

But some things remained the same after he took over. One, perhaps appropriate considering his musical background, was his retention of the subhead: “Conducted by Sigismund Blumann” for the journal’s long-established editorial column The Amateur And His Troubles previously edited by Paul Douglas Anderson. This time, an actual orchestra conductor was indeed stepping in to conduct editorial affairs! Keeping this personal touch intact-especially to those who knew him as someone passionate of music his entire life, was just one way of his remaining connected with readers as well as professional and social acquaintances in the Bay Area. Under Sig’s moderation, the column continued to offer advice dispensed by any number of well regarded authors who broke down and offered solutions to problems encountered by amateurs in the field relating to anything from photographic equipment to darkroom dilemmas.

“Lugubrio”: Sigismund Blumann, American: 1927 or before: gelatin silver print: 20.8 x 16.4 | 25.3 x 20.1 cm: This image, reproduced as a large halftone, was published on the same page as an accompanying poem of the same title for the April, 1927 issue of Camera Craft. The scene was most likely taken along the Pacific coastline. From: PhotoSeed Archive

His second column, a new feature which debuted with the November, 1924 issue, was called CHIT CHAT About our friends. A vehicle for Sig’s effusive boosterism of photography in general, both professional and amateur, it was written in a style that might best be described, amusingly, as slightly syrupy in tone but delivered with erudition. Profiles on photographers he found interesting, and news of California camera clubs were a constant monthly feature of the column in addition to news of major upcoming exhibitions as well as critiques and results from those salons happening not only on the West Coast but throughout the United States and beyond. Comically subtitled: “Ye Editor Retaileth Newes of Ye Profession And In Quaint Italics Titillateth Ye Sphynx With Hys Quill“, the column’s “titillations” were often just longish aphorisms managing implied or direct associations to something photographic. Appearing rather infrequently at the column’s outset and disappearing altogether by August, 1931 when this inventive take on the English language was eliminated, they appeared from time to time, with several reprinted below for his January, 1926 column:

“Every time you get the best of a customer you have cheated yourself.”

“The most expensive lens may not be the best but the cheapest is pretty sure to be the worst.”

“Past Presidents Nite At Toyon Inn Feb. 15- 1927” : by artist W.A. Bridge, American -California? : Used as a halftone in the March, 1927 issue of Camera Craft, this humorous cartoon illustrated a dinner dance commemorating a gathering of past presidents of the Pacific International Photographers’ Association which took place at San Leandro’s Toyon Inn on Feb. 15, 1927. Sigismund Blumann, who served as host of the event, made sure to comment in the pages of Camera Craft magazine that “refreshments” of a most unusual kind: ie: inebriating, were served at the event during the era of American Prohibition. From: California State Library: Archive.org

Lastly, and most importantly, one of the most personal reasons for Camera Craft’s success under Sig was his entirely self-written Under the Editor’s Lamp column, debuting with the April, 1926 issue. Already a fixture by means of the pen to his many readers-in prose as well as poetry- the column gave a final say so to speak to his personal views-conservative to be sure-on just about anything going on regarding photography and musings on current events. With accompanying column artwork by California artist W.R. Potter portraying Sig kicking back while puffing his pipe and seated at a library desk, the column became an effective way for this journal’s Editor-in-Chief to assume the role of oracle and brand ambassador. Sig’s short forward for his first Under the Editor’s Lamp :

When the desk is cleared of paste-pot and shears and the lamp is lit, it is good to put a match to the freshly loaded, old pipe and take a puff or two, letting the mind’s mind relax into mere dreams. The lamp is a sentimental fiction, of course, being a standardized glass bowl with a bulb glowing through, but the pipe is real, the mood is sincere, and we hope the mind exists, more or less.

Out go our thoughts to readers unseen, perhaps never to be met except as a large, critical, voracious body of men and women who consume the forty-eight pages of pictures and text and off-hand decide the fare has been very good, fair, or rotten. Little do they care what labor, what hopes, what ambitions went into every line and every illustration. Why should they. The best is no better than their due. (p.180)

“A Spot for Reflections”: Sigismund Blumann, American: ca. 1925-30: gelatin silver print : 9.8 x 6.5 | 18.2 x 14.5 cm : perhaps taken in Oakland or the Inverness area of Marin County, CA, this is a fine example of Blumann’s pictorialist work in which he has titled the composition in gold lettering and triple-mounted the image onto fine art paper supports. From: PhotoSeed Archive

M.Q. Developer to Develop Good Feeling

Because Camera Craft billed itself the official organ of the Pacific International Photographers’ Association, (PIPA) with owner Ida M. Reed acting as Secretary and headquartered in the same San Francisco offices as the journal, (703 Market in Claus Spreckles Building) news of the Association-which covered a wide western geographic area including membership from Alaska, Alberta, Arizona, British Columbia, California, the Hawaiian Islands, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, Utah and Washington states- became a regular monthly feature of the previously discussed Chit-Chat column. By 1927, Sig was hitting full-stride at Camera Craft, his writing skills undoubtedly honed through his reminisces featured in the Editor’s Lamp column.

Detail: “Vera in the Woods”: Sigismund Blumann, American: 1920-25: hand-colored gelatin silver print: 24.2 x 18.6 cm: Taken among a stand of Redwood trees, perhaps in the present-day Muir Woods National Monument in Marin County, CA, the subject of this photograph is believed to show the photographer’s youngest daughter Vera Blumann, b. 1911. Blumann was in love with the outdoors, and frequently took part in extended camping trips with family members to hike and photograph areas of beauty in California and the Pacific Northwest-trips he wrote about in the pages of Camera Craft. See variant: Minneapolis Institute of Arts: Accession #99.231.15. From: PhotoSeed Archive

The following account is a result of this, of Sig’s prodigious social engagement with members active in the Bay-area camera club scene. In a humorous yet telling example of his own admission to preserve the rightful history of one particular PIPA (often referred to as a club) meeting for Chit-Chat, the March, 1927 issue duly reported on the Past Presidents Night dinner dance at San Leandro’s Toyon Inn on Feb. 15, 1927. Taking place when Prohibition was still the law of the land in America, (9.) Sig’s account made sure to include the lengths employed at the soirée in order for those attending to enjoy the social, and inebriating benefits of some “liquid cheer”:

But hold, before we close it must be chronicled as it shall be inscribed in the archives of the club that each guest found a developing tray and two glass graduates before him. It was a paper tray, so that when dropped the falling tray might not raise the deuce. In one of the two ounce graduates water was served and in the other M.Q. developer to develop good feeling. A bucket of Hypo was kept in the ante-room to fix the police, and everything was provided to make a perfect picture except bromide. If any was needed it was the next morning. (p. 145: M.Q. was an alkaline developer for gelatine emulsions combining Metol and hydroquinone)

“Yosemite Falls | Yosemite Valley”: Sigismund Blumann, American: dated 1926 & signed: “Dry Point Etching” ie: most likely a Kallitype or bleached and toned print on Vitava E (tching) chlorobromide paper: 13.1 x 9.0 | 23.7 x 16.5 cm: A specialist in alternative darkroom processes, particularly Kallitype, Blumann perfected his “Dry Point Etching” process and described it in lengthy articles in Camera Craft in 1925 and later in July, 1934 for his own Photo Art monthly using the pen name “Charles H. Fitzpatrick.” This finished etching showing Yosemite Falls was originally taken as a photograph by Blumann in the Spring of 1925. Both photo and etching were illustrated side-by-side as halftones in the October, 1925 Camera Craft article titled “Making Photographs Into Dry Point Etchings”. See the following citation at end of this caption in Notes field for a working description of the “Dry Point Etching” process. (11.) From: PhotoSeed Archive

Camera Nut to the End

Considering he was having an awfully good time in his position as Editor-in Chief, an observation certainly not witnessed by this writer but most obvious by the written evidence left for posterity, Sig’s resignation at the end of July, 1933 does seem a bit abrupt. Historian Christian A. Peterson speculates he and owner Ida M. Reed “parted ways over deep differences.” (10.) But with the installation of Camera Craft veteran George Allen Young to replace him, Sig was none the less given deserved praise by owner Ida Reed the following month:

Since 1924 we, and the readers of this magazine, have enjoyed his contagious enthusiasm, and his wide technical knowledge of photography,. He leaves with our best wishes for success and happiness. (p. 387)

Earlier, for his final Under the Editor’s Lamp column written in July, 1933 and published the next month, his nine-year run at the journal concludes with a perhaps knowing, but certainly wistful remembrance of his good times spent there. Recounting adventures in photography that summer while traveling the California High Sierra, Sig first gives accolades to the efforts U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt was giving to get American industry moving again during the ongoing Great Depression before concluding by stating his own continued love affair with photography:

Does thinking of Yosemite and speaking of photography seem like reductum ad absurdum to you? It should not for I can allow myself so very short a time in that garden of The God and I can so effectively carry some of its glory and inspiration over the rest of the year with what my camera has enabled me to bring home, that it is natural to raise the picture, as near as imagination makes possible, to the original.

As I look at the screen and project the pictures, studying how to express my reactions when on the spot, I once again smell the pines and hear the rush of the Merced as it boils over the Happy Isles. In the quiet and the benignancy of the red light fancy builds Half Dome, El Capitan, and the Domes anew.

The old rags that made us free. The open spaces that made us immortal in spiritual disembodiment. The camera that vitalized every hour of the day with its assurance of creative picture making. Friends, I am glad, very glad, to be a camera Nut. (p. 343)

With that, a poem by Sig somehow seems a good fit in ending this remembrance about the young boy who moved to California and proceeded through hard work and perseverance to embrace the Golden State as his own. Along with possessing the gift of innumerable talents and more than a few dreams, he managed to share them with many others.

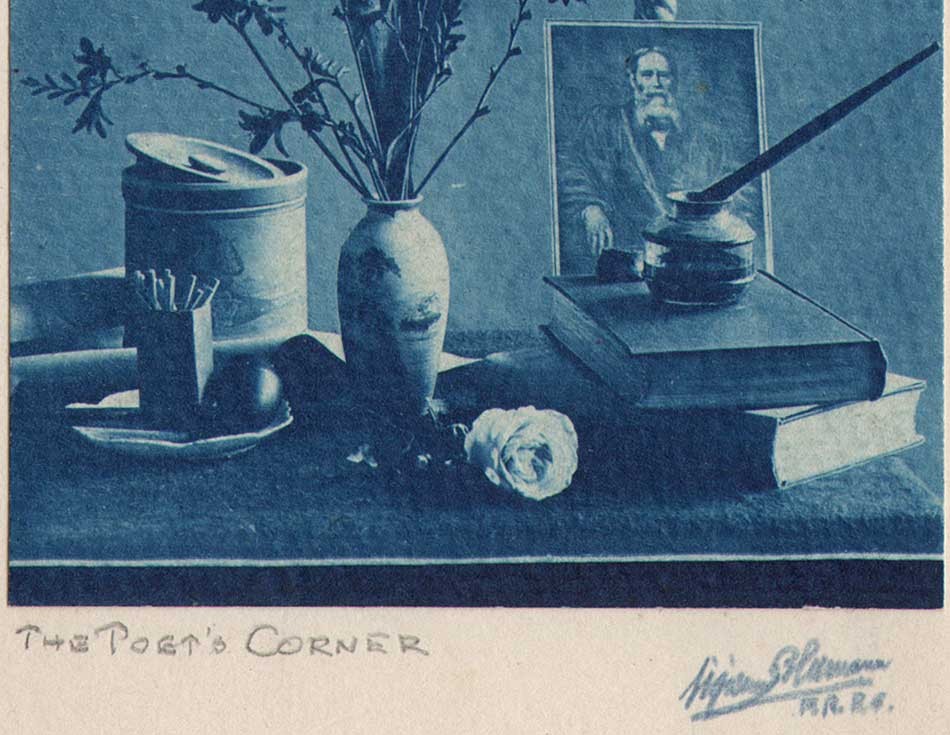

THE QUIET CORNER by Sigismund Blumann

A PIPE, some books, a flower or two,

The picture of one gone before

Who stands without the open door

And shall not die.

When work is through

Some day, some day, when rest is won

And the long, long duty-season done,

I’ll sit me down to taste the best

Of books, tobacco, men and things:

To listen when the spring-bird sings—Looking in peace toward the West.

Against that day, and I am spared,

My quiet corner stands prepared.

To see all work by Sigismund Blumann in the PhotoSeed Archive please go here.

Detail: “The Poet’s Corner” or “The Quiet Corner”: Sigismund Blumann, American: 1933 or later: toned pigment print: 10.6 x 7.5 | 16.9 x 11.6 cm: The author’s trusty pipe can be seen at left in this still-life table top study reproduced as the frontis halftone illustration for the August, 1927 issue of Camera Craft. From: PhotoSeed Archive

NOTES:

1. see: Early Years in Photography: “Sigismund Blumann, California Editor and Photographer”, by Christian A. Peterson in History of Photography, vol. 26, no. 1. (Spring 2002) p. 59.

2. Ibid: in: Photo Art Monthly, 1933-40: p. 73

3. It would not be until July, 1934, in an updated version of this 1925 Camera Craft article on describing the process of turning photographs into dry point etchings in Photo-Art Monthly, that evidence of Fitzpatrick and Blumann being the same person would seem to be confirmed. In it, the illustrated example of Blumann’s credited photograph titled “Land’s End” is also shown reproduced into the converted dry point etching with credit given to Fitzpatrick. Editorially, it might seem odd to continue this pen-name fiction with Blumann even going to lengths to construct a suspect history in 1925 of “Fitzpatrick’s” own beginnings although the reason was most likely intended as another way of imparting education on a topic deemed worthy and educational enough in the eyes and mind of the editor himself.

4. Copies of at least 43 documentary photographs, with several corresponding paper negative envelopes dated 1901 by Sigismund Bluman, were donated by his family to the California Historical Society where they can be viewed as part of the collection “The Chinese in California: 1850-1925.” The following link includes a smaller sampling of later printed examples, (some hand-colored) along with a rare surviving example titled “Ruin” (a detail included with this post) from 1906 of earthquake damage taken by the photographer as well as several portraits of Sig taken by others.

5. see: citation #1: p. 54.

6. excerpt: introduction: Making Photographs Into Dry Point Etchings: by Charles H. Fitzpatrick Illustrated by the Author: in: Camera Craft: October, 1925: San Francisco: p. 485.

7. see: citation #1 p. 54

8. Ibid: introduction: p. 53

9. American Prohibition was a nationwide constitutional ban on the sale, production, importation, and transportation of alcoholic beverages.

10. see: citation #1 p. 65

11. In order to make one of these etchings, the article instructs that after first selecting a printed photograph with little detail, the next step is to: “draw as much as he can on the photograph, using Higgins’ Water Proof India Ink. When this is absolutely dry the silver is completely bleached out with Bichloride of Mercury or Iodine-Iodide bleachers. The pen shading and finishing is then done with care, when the bleached and washed print has been dried.” From here, the article states a copy negative must then be made which is used to make the final second-generation finished (and reduced for effect) “etchings” using various grades of photographic paper: “The method of reproducing drawings is very simple. Place drawing on wall or easel and camera on firm support exactly centering lens on drawing, making exposure on a slow copy plate by diffused daylight or electric light, and develop for contrast. In copying it is advisable to reduce the image one-third smaller than the original as a finer line is thus secured which improves the finished print. The writer prefers a buff stock, matt paper of medium grade and heavy; and has found Vitava E just right: This is a matter of choice, however, as good prints may be secured on Azo, Velox, Cyco, Kruxo, Defender, Haloid, Barston, Charcoal Black or other matt papers. Proceed as in ordinary photographic printing then tone by re-development, using whatever process you prefer. I use Royal-Re-developer with pleasing results.” In the later 1934 article: “Etchings From and With Photographs”, “Fitzpatrick”goes further in depth on this etching process, adding that after the second-generation reduced copy print is made, the print could be “treated through all the usual solutions in the usual way and may be developed in any of the prescribed formulae for blue-black, jet-black, warm-black, or dark brown tones. Or it may be subsequently toned by the bleach and redevelop methods. The particular brown of an etching is easily gotten on Vitava Athena with a developer containing Athenon. Azo P-2 or 3, Vitava Athena E, Novira in the matt smooth or rough are all fine for the purpose. Gevalux gives a wonderful image in a true carbon black color and velvet crayon patine.” Continuing, the article offers a summary of the entire process: “That is all there is to the whole thing. You could not complicate it if you tried. Just make an enlargement, work on it with pen and ink, bleach out the silver leaving the ink image, photograph the line drawing, make as many etching-prints from the copy negative as you wish. Where can you go wrong? How can you fail?” He concludes by saying the maker of these etchings could also go “one step further by using hand-sensitized photographic papers for this final second-generation completed “etching”: “Furthermore, should you desire to print on colored papers or card- board of such surface as cannot be bought ready sensitized it will be a simple matter to sensitize any stock with the well known Blue Print solutions, or if the various shades of brown and black are wanted to resort to Kallitype. These processes are as cheap as they are easy to compound and use; they work on any paper not too saturated with chlorides or unfixed dyes. Kallitype is moreover a beautiful process in itself and prints endure according to the care in making them.”