Detail: 1895: “LA VIERGE A L’ENFANT”, (The Virgin and Child) Baron Adolph de Meyer: hand-pulled photogravure from: Bulletin du Photo-Club de Paris: December, 1896: 17.1 x 12.1 cm | 27.2 x 19.7 cm: PhotoSeed Archive

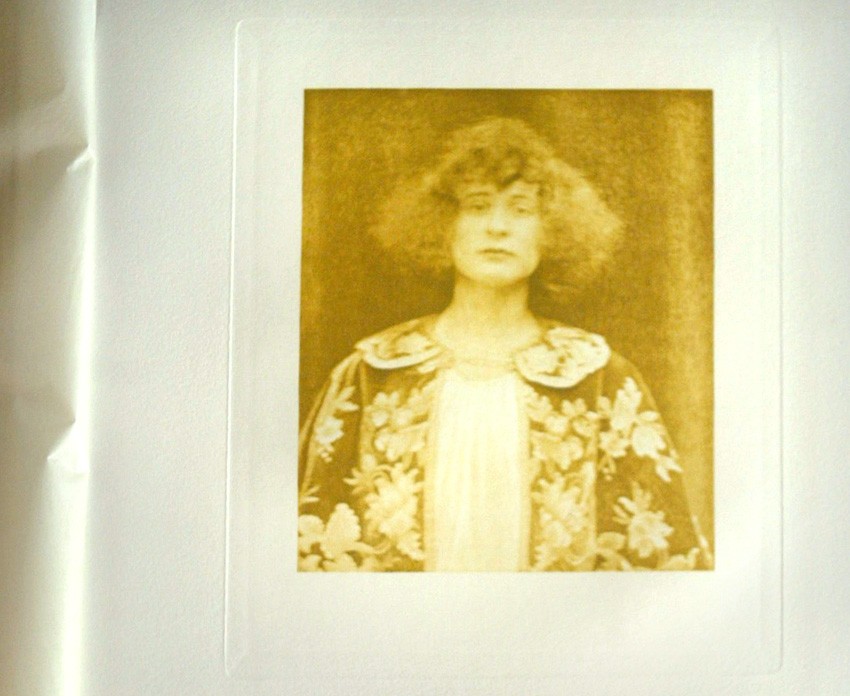

No matter the evidence, in this case-the title assigned to it: Portrait de M. Peters– I refused to believe my eyes. That’s why I initially tagged it Portrait: Woman on this site: a most strange, mysterious and striking study of a woman with frizzed-out hair—or so I thought: a hand-pulled photogravure tinted in yellow hues— which made up the final plate included in the 1894 portfolio Première Exposition d‘Art Photographique. (First Exposition of Art Photography) The work was issued by the Photo-Club de Paris that year for their very first exhibition which took place at the Georges Petit galleries in Paris from January 10-30th.

An American in Paris: actor and poet William Theodore Peters (1862-1904) is the subject of this portrait by English photographer Eustace Calland reproduced as the final plate in the “Première Exposition d‘Art Photographique” portfolio issued in 1894. Detail of plate showing tissue guard and plate marks: image: 13.9 x 11.8 cm: planche LVI

But now thanks to a chance encounter with the photo reproduced in the English journal The Studio, I now know the truth, and have subsequently updated the tag to Portrait: Men:

The Portrait from life, by Mr. Eustace Calland, is a costume study of Mr. William Theodore Peters—as Bertrand de Roaix. The photograph, we understand, is now being exhibited at Paris. Mr. Peters is the author of a forthcoming volume of verse, containing, among other numbers, the Pierrot of a Minute, a charming poem already familiar through the author’s recitation in public. (1.)

And so it was not a woman who English photographer Eustace Calland (1865-1959) depicted but a man: the American poet and actor William Theodore Peters. (1862-1904) A quick online search of Peters gave me the impression he may have been the poster child for Decadence with a capitol D exemplified by 1890’s Paris. (2.) Someone who in the immortal words of American comic Steve Martin might have well stood in for the original “One Wild and Crazy Guy.” Peters lifestyle caught up with him however, and he is reported to have died in that city in poverty- not even 40 years old.

Since it was exhibited in January, 1894 in the Photo-Club de Paris exhibit, this portrait of Peters was most likely taken sometime in 1893. Another intriguing aspect of the photograph is a cloak he wears in it. As I don’t think it is a coincidence, I’m going to connect the dots here and conclude this post by going further: this is the very cloak made famous by Peter’s friend, the English poet and playwright Ernest Christopher Dowson, (1867-1900) who finished penning the following lines in August, 1893 (3.) with the title:

To William Theodore Peters on his Renaissance Cloak

The cherry-coloured velvet of your cloak

Time hath not soiled: its fair embroideries

Gleam as when centuries ago they spoke

To what bright gallant of Her Daintiness,

Whose slender fingers, long since dust and dead,

For love or courtesy embroidered

The cherry-coloured velvet of this cloak.

Ah! cunning flowers of silk and silver thread,

That mock mortality? the broidering dame,

The page they decked, the kings and courts are dead:

Gone the age beautiful; Lorenzo’s name,

The Borgia’s pride are but an empty sound;

But lustrous still upon their velvet ground,

Time spares these flowers of silk and silver thread.

Gone is that age of pageant and of pride:

Yet don your cloak, and haply it shall seem,

The curtain of old time is set aside;

As through the sadder coloured throng you gleam;

We see once more fair dame and gallant gay,

The glamour and the grace of yesterday:

The elder, brighter age of pomp and pride. (4.)

Ten years after these lines were written Peters and Dowson were both dead, with this portrait by Calland possibly being the sole surviving image known of Mr. William Theodore Peters.

1. The Studio: An Illustrated Magazine of Fine and Applied Art: London: Offices of the Studio: Vol. II: 1894: p. 138 (photograph appears on p. 139)

2. “He was, as an irreverent American once said of him, that “rara avis in human kind,—a poet with money,” and so stole time from his verse-making to give charming little dinners, the lists of which were redolent with Lady This and Countess That, since he knew nearly every woman of title, native or sojourner, in Paris.”: excerpt: Verses Written in Paris by Various Members of a Group of “Intellectuals”: in: The Critic: An Illustrated Monthly Review of Literature, Art and Life: New Rochelle, New York: Vol. XXXIX: 1901: pp. 38-39

3. notes: Ernest Dowson Collected Poems: edited by R.K.R. Thornton: University of Birmingham Press: 2003: pp. 257-258

4. included in: The Poems of Ernest Dowson: Dodd, Mead and Company: New York: 1922: pp. 144-145

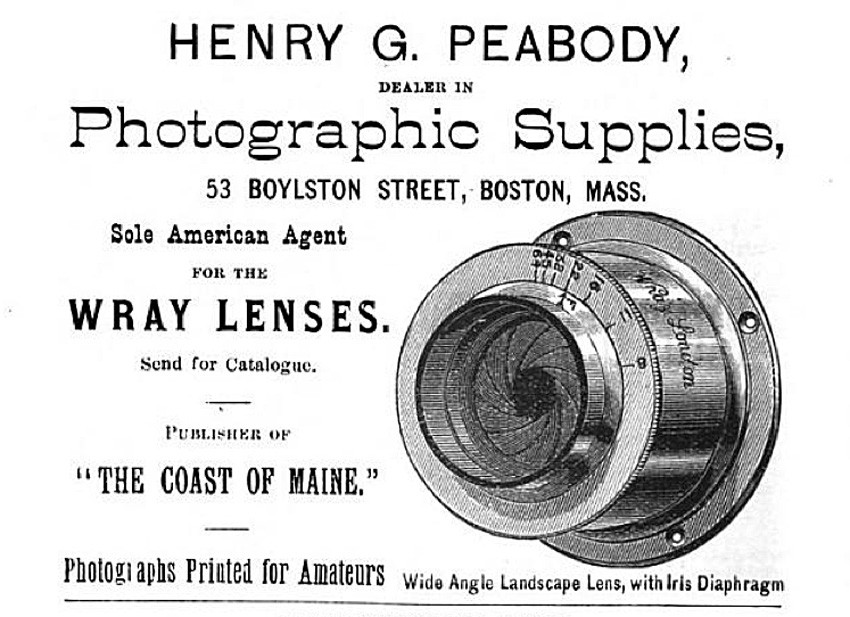

When photographer and photographic supply dealer Henry Greenwood Peabody of Boston compiled and self-published the oblong quarto volume The Coast of Maine: Campobello to the Isles of Shoals in 1889, he offered it for sale by subscription, advertising it along with the fact he was the sole American agent for Wray lenses in photographic journals including Anthonys.

“Wing and Wing”, (16.3 x 22.7 cm) one of fifty plates reproduced by the photo-gelatine (collotype) process by the Photogravure Company of New York in the volume: The Coast of Maine: 1889: published by Henry G. Peabody, 53 Boylston Street, Boston.

These lenses were first manufactured in London by a gentleman named William Wray beginning in 1850. Peabody, presumably using a Wray lens or lenses outfitted on his 8 x 10″ view camera, had scoured the rocky Maine coastline the year before in search of the picturesque. The published results in The Coast of Maine included 50 full size plates, done using the very fine photo-gelatine process, (collotype) a specialty of Ernest Edward’s Photogravure Company of New York. These plates, most of which show the coastline in proximity to the ocean; multiple lighthouse views but surprisingly very few boats, (Peabody was an important photographer of sailboats on the high seas) are supplemented with poetry and prose by seven writers, including the American poet and writer Celia Thaxter. (1835-1894)

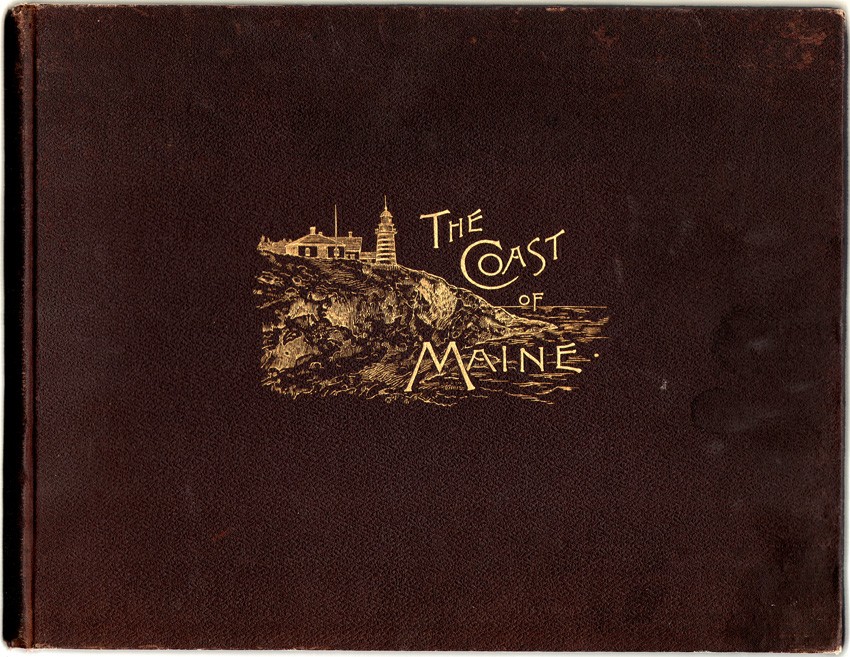

The artist J.E. Hill is credited as having done the drawings appearing in “The Coast of Maine: Campobello to the Isles of Shoals”, published in 1889 by photographer and at the time, photographic supply house owner Henry Greenwood Peabody of Boston. Hill’s work can be seen here embossed in gilt on the cover of the volume. (27.4 x 35.5 x 2.5 cm) Additional Hill drawings appear as vignettes opposite many of the plates in the book.

Her poem Reverie had been first copyrighted as early as 1878 and published in 1880 in her collection of poems titled Drift-Weed in Boston. Although this long-form poem predates the above photo Wing and Wing by at least ten years, Peabody paired it in double columns opposite this lone sailboat photograph (in full sail) appearing in the work.

Reverie

The white reflection of the sloop’s great sail

Sleeps trembling on the tide;

In scarlet trim her crew lean o’er the rail,

Lounging on either side.

Pale blue and streaked with pearl the waters lie

And glitter in the heat;

The distance gathers purple bloom where sky

And glimmering coast-line meet.

From the cove’s curving rim of sandy gray

The ebbing tide has drained,

Where, mournful, in the dusk of yesterday

The curlew’s voice complained.

Half lost in hot mirage the sails afar

Lie dreaming still and white;

No wave breaks, no wind breathes, the peace to mar:

Summer is at its height.

How many thousand summers thus have shone

Across the ocean waste,

Passing in swift succession, one by one,

By the fierce winter chased!

The gray rocks blushing soft at dawn and eve,

the green leaves at their feet,

The dreaming sails, the crying birds that grieve,

Ever themselves repeat.

And yet how dear and how forever fair

Is nature’s kindly face,

And how forever new and sweet and rare

Each old familiar grace!

What matters it that she will sing and smile

When we are dead and still?

Let us be happy in her beauty while

Our hearts have power to thrill.

Let us rejoice in every moment bright,

Grateful that it is ours;

Bask in her smiles with ever fresh delight,

And gather all her flowers;

For presently we part: what will avail

Her rosy fires of dawn,

Her noontide pomps, to us, who fade and fail,

Our hands from hers withdrawn?

Celia Thaxter.

Advertisement showing wide angle Wray landscape lens with iris diaphragm manufactured in London from: “The International Annual of Anthonys Photographic Bulletin”: New York: 1889: from p. 98 of the advertising section in the rear of the volume. Photographer Henry Peabody is believed to have used a similar Wray lens for photographs appearing in the volume “The Coast of Maine” published by him in 1889.

This is an example of one of several lighthouse plates: “The Nubble : York, ME” (15.6 x 22.5 cm) taken by photographer Henry Peabody and published as a full-page photo-gelatine (collotype) plate in “The Coast of Maine” in 1889. The view shows the Cape Neddick “Nubble” Light near the entrance to the York River. The light continues to operate today.

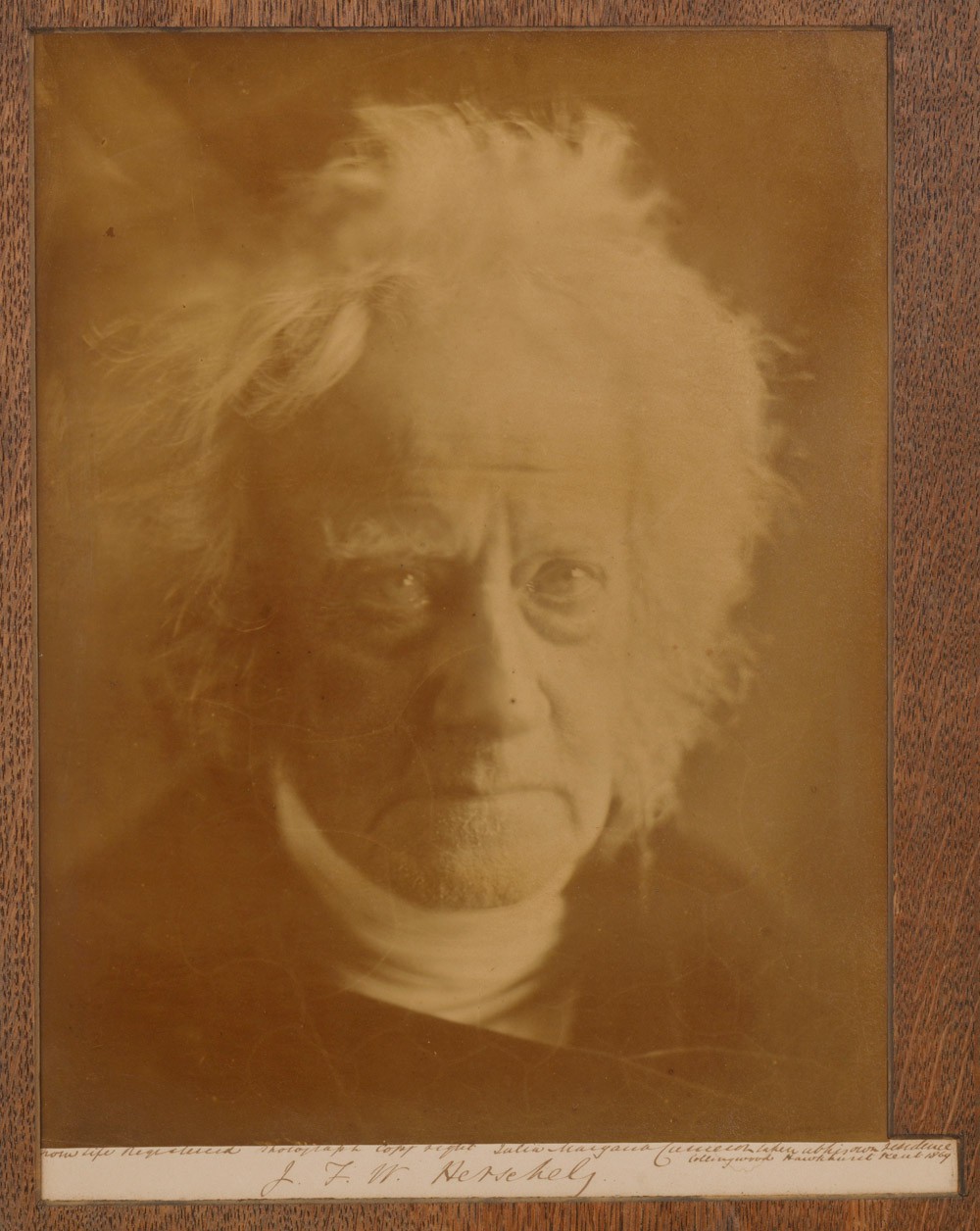

Sir John Frederick William Herschel is someone to pay attention to when thinking about photography. And for no other reason? He is credited with coining the very word “photography” in the English language. (with apologies to French-Brazilian painter and inventor Hércules Florence)

Herschel–famed English astronomer and, for our purposes here, photographic pioneer–is one of the unsung heroes of what we know as modern photography. For those lucky enough to have worked in a wet darkroom, it was Herschel the scientist and chemist who discovered and corresponded with William Henry Fox Talbot that sodium thiosulphite, commonly known as “hypo”, could “fix” silver halides, and therefore was a reliable means of making a photograph permanent.

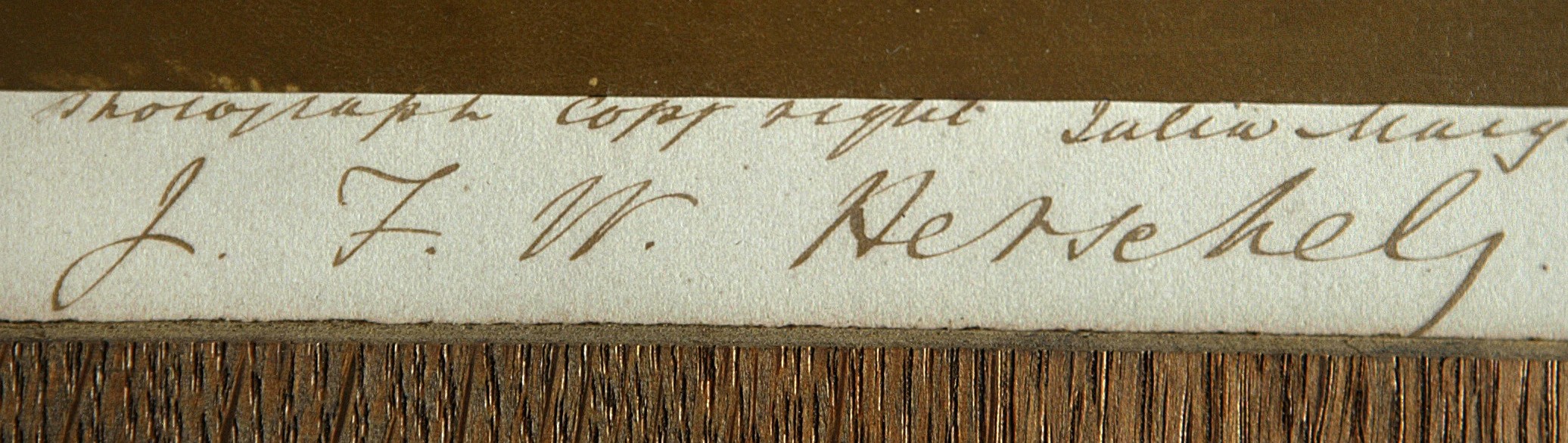

The photographic mount ink inscription reads in full left to right: “From Life Registered photograph copyright Julia Margaret Cameron taken at his own residence Collingwood Hawkhurst Kent 1867” and then signed below: J. F. W. Herschel

Buried next to Sir Isaac Newton in Westminster Abbey, Herschel’s genius was an ability to make science understandable to both the curious and the more educated through his writings and presentations to the established scientific bodies of the mid 19th century.

As a collector, I’ve always been drawn to the art of photography. However, I have an appreciation of the science that has always been the important backdrop for making modern photography possible in the first place, and Herschel’s role in that science. This wonderful photographic likeness of Herschel, taken by his dear friend Julia Margaret Cameron, has always been of interest to me as a collector because it combines both art and science.

A Cameron portrait of Herschel appeals on many photographic collecting levels. It is considered one of the great “head” portraits that Cameron was famous for-perhaps more so because of its brooding and mysterious nature; a symbolic likeness of a man whose life was spent on a quest for discovery and explanation of the unknown.

But It has never been my intention as a collector to purchase a photograph because it is considered one of the “greatest hits” in the history of the medium. On the contrary, I am continually surprised how much wonderful material is available of the unknown and unsung photographer, often for the price of a song. The beauty of collecting photography in our modern age is that its’ story has not been fully chronicled nor even discovered, and one of the aims of PhotoSeed will be to fill in some of these blanks for the record.

The four known portraits of Herschel were taken late in his life in 1867 by Cameron. Through much luck I was able to purchase this one, a mounted (with wood veneer overlay) albumen example at auction in 2004 from a gentleman who originally purchased it at auction in Dublin, Ireland in 2003.

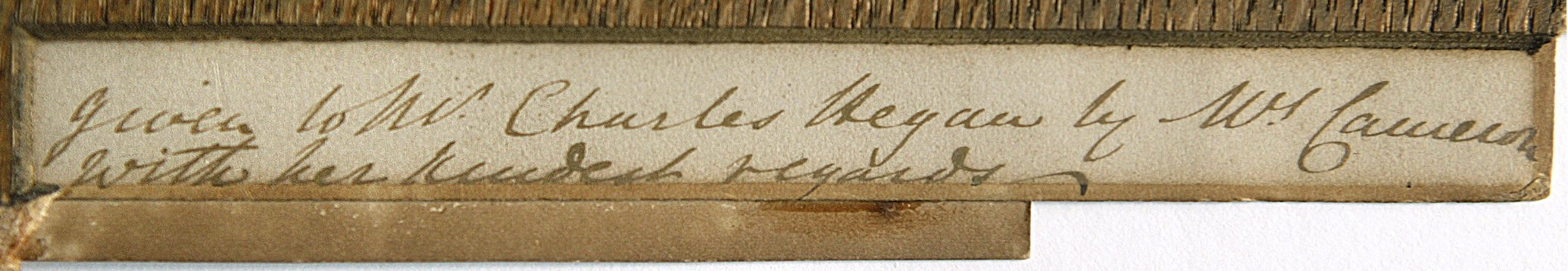

Twice personally signed by Cameron, the bottom right hand corner of the mount provides the following inscription by her: “Given to Mr. Charles Hegan by Mrs. Cameron with her kindest regards.”

Naturally, I was intrigued as to the mysterious Mr. Hegan was and how he might have known Cameron. Through research, I tracked down the family who originally consigned the Herschel portrait as well as other items to the Irish auction. And this is why photographic sleuthing pays off. It turns out that in 1899 this photograph was a wedding present from Hegan to one Joseph Alfred Hardcastle. (born 1868) Never heard of him? It turns out he was Herschel’s grandson, and the photograph had stayed in Hardcastle’s family until 2003. A very nice provenance indeed.

A friend of a member of the present-day Hardcastle family in Ireland did research on my behalf, trying to figure out who Hegan was and his possible connection to Cameron, but came up empty. Later, my own research determined Hegan (Charles John Hegan) was a fellow of London’s Royal Geographical Society (elected 1873) who likely knew Hardcastle through scientific and perhaps family connections (they both attended Harrow but over 20 years apart). Ownership of the Herschel portrait makes complete sense as both Hegan and Hardcastle were devoted to scientific endeavors. On this front, Hegan travelled to South America to conduct fluvial research on behalf of the Royal Geographical Society and Hardcastle, a fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society who lectured and conducted research relating to astronomy, was appointed director of the Armagh Observatory in Northern Ireland, but died suddenly in 1917 while in route there.

So talk about the perfect wedding gift. Hardcastle’s love was astronomy. Although only three years old when his grandfather was buried next to Newton, Herschel would have been proud of a grandson following in his own esteemed footsteps.

The photograph is signed boldly (believed to be in Cameron’s hand) : J. F. W. Herschel

There are pencil notations by a framer most likely done after the 1899 wedding, including “Show all writing” on the back of the original Cameron mounting board. Visible as well and centered at foot of mount is a verso impression of a Colnaghi blindstamp, indicating the photograph was once marketed by Cameron through the well-known London gallery. Somehow, the print made its’ way back to Cameron and she personally signed and presented it to Hegan at an unknown date: “given to Mr. Charles Hegan by Mrs. Cameron with her kindest regards.”