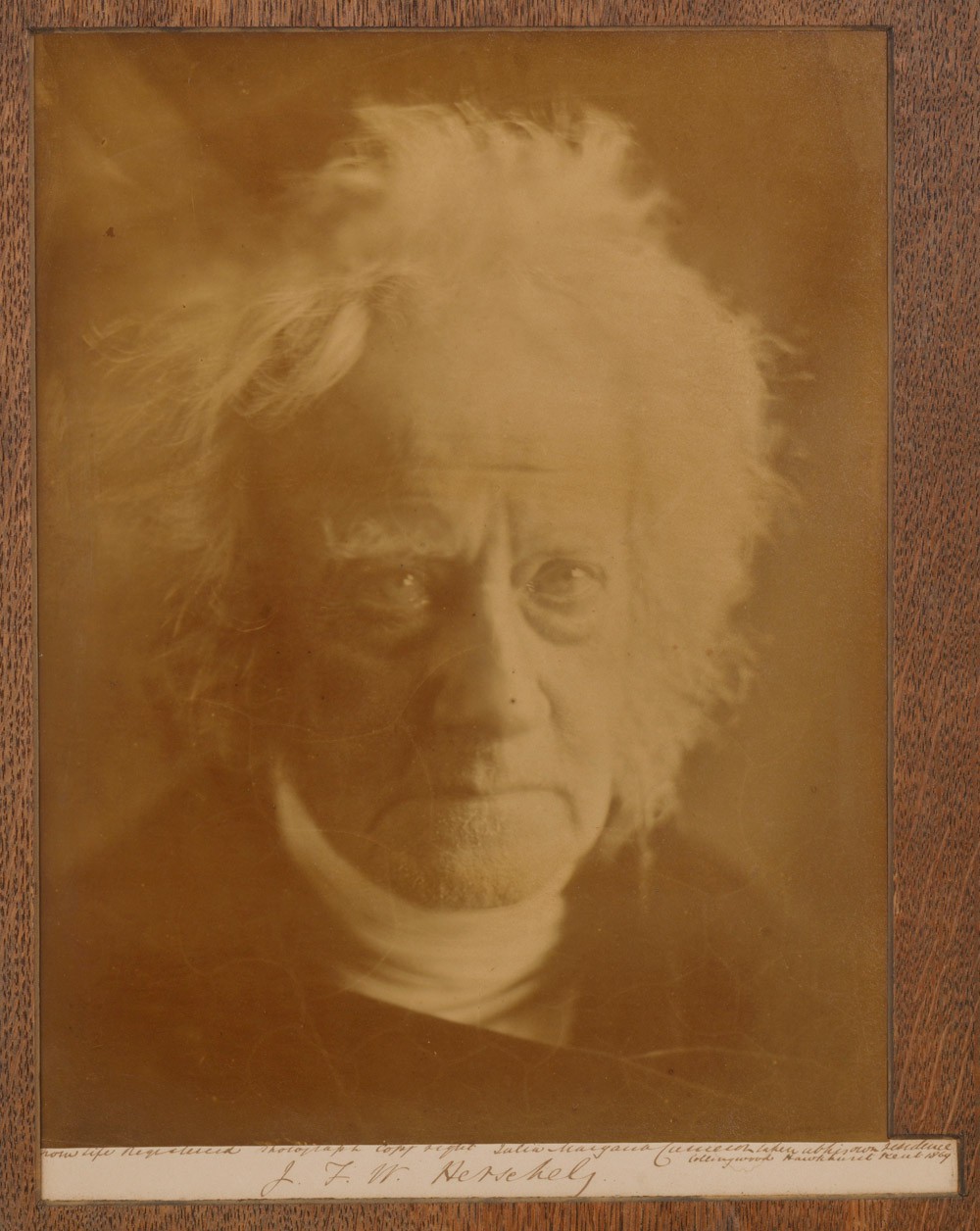

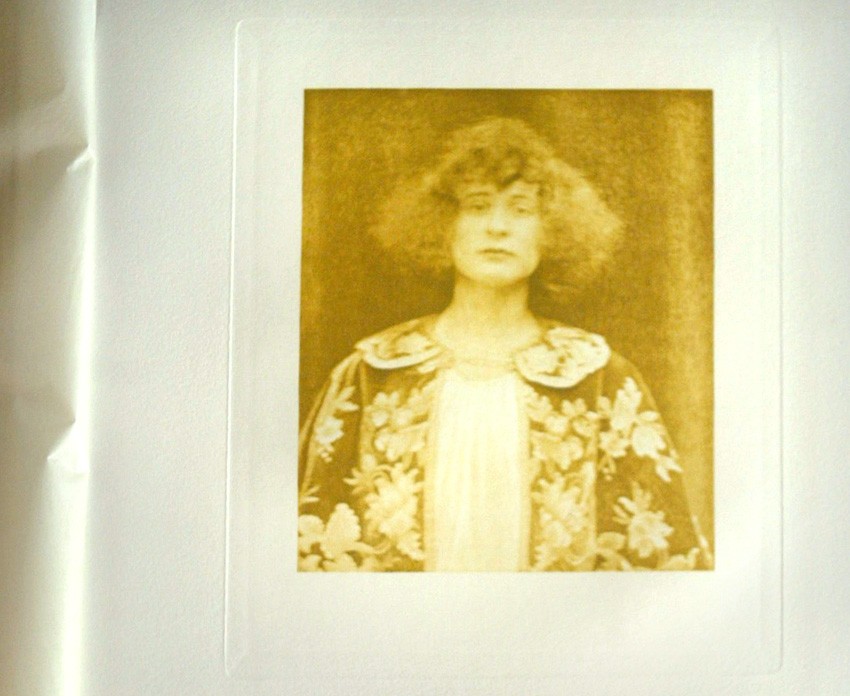

No matter the evidence, in this case-the title assigned to it: Portrait de M. Peters– I refused to believe my eyes. That’s why I initially tagged it Portrait: Woman on this site: a most strange, mysterious and striking study of a woman with frizzed-out hair—or so I thought: a hand-pulled photogravure tinted in yellow hues— which made up the final plate included in the 1894 portfolio Première Exposition d‘Art Photographique. (First Exposition of Art Photography) The work was issued by the Photo-Club de Paris that year for their very first exhibition which took place at the Georges Petit galleries in Paris from January 10-30th.

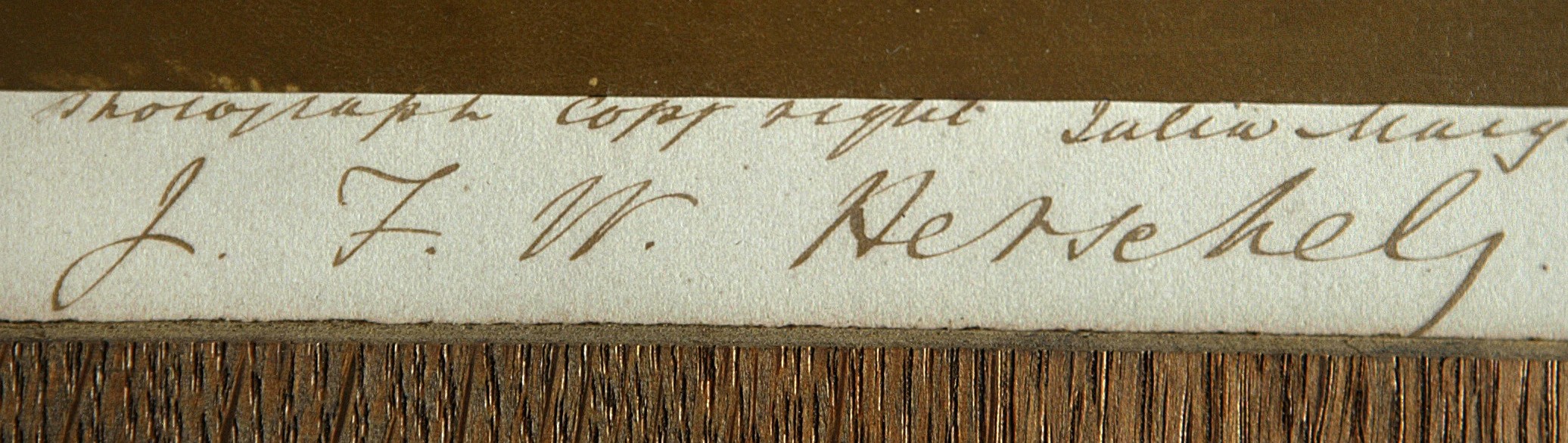

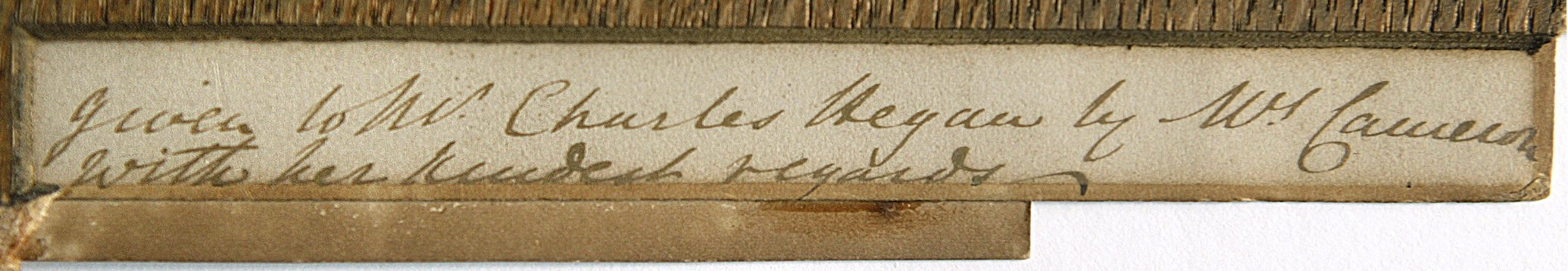

An American in Paris: actor and poet William Theodore Peters (1862-1904) is the subject of this portrait by English photographer Eustace Calland reproduced as the final plate in the “Première Exposition d‘Art Photographique” portfolio issued in 1894. Detail of plate showing tissue guard and plate marks: image: 13.9 x 11.8 cm: planche LVI

But now thanks to a chance encounter with the photo reproduced in the English journal The Studio, I now know the truth, and have subsequently updated the tag to Portrait: Men:

The Portrait from life, by Mr. Eustace Calland, is a costume study of Mr. William Theodore Peters—as Bertrand de Roaix. The photograph, we understand, is now being exhibited at Paris. Mr. Peters is the author of a forthcoming volume of verse, containing, among other numbers, the Pierrot of a Minute, a charming poem already familiar through the author’s recitation in public. (1.)

And so it was not a woman who English photographer Eustace Calland (1865-1959) depicted but a man: the American poet and actor William Theodore Peters. (1862-1904) A quick online search of Peters gave me the impression he may have been the poster child for Decadence with a capitol D exemplified by 1890’s Paris. (2.) Someone who in the immortal words of American comic Steve Martin might have well stood in for the original “One Wild and Crazy Guy.” Peters lifestyle caught up with him however, and he is reported to have died in that city in poverty- not even 40 years old.

Since it was exhibited in January, 1894 in the Photo-Club de Paris exhibit, this portrait of Peters was most likely taken sometime in 1893. Another intriguing aspect of the photograph is a cloak he wears in it. As I don’t think it is a coincidence, I’m going to connect the dots here and conclude this post by going further: this is the very cloak made famous by Peter’s friend, the English poet and playwright Ernest Christopher Dowson, (1867-1900) who finished penning the following lines in August, 1893 (3.) with the title:

To William Theodore Peters on his Renaissance Cloak

The cherry-coloured velvet of your cloak

Time hath not soiled: its fair embroideries

Gleam as when centuries ago they spoke

To what bright gallant of Her Daintiness,

Whose slender fingers, long since dust and dead,

For love or courtesy embroidered

The cherry-coloured velvet of this cloak.

Ah! cunning flowers of silk and silver thread,

That mock mortality? the broidering dame,

The page they decked, the kings and courts are dead:

Gone the age beautiful; Lorenzo’s name,

The Borgia’s pride are but an empty sound;

But lustrous still upon their velvet ground,

Time spares these flowers of silk and silver thread.

Gone is that age of pageant and of pride:

Yet don your cloak, and haply it shall seem,

The curtain of old time is set aside;

As through the sadder coloured throng you gleam;

We see once more fair dame and gallant gay,

The glamour and the grace of yesterday:

The elder, brighter age of pomp and pride. (4.)

Ten years after these lines were written Peters and Dowson were both dead, with this portrait by Calland possibly being the sole surviving image known of Mr. William Theodore Peters.

1. The Studio: An Illustrated Magazine of Fine and Applied Art: London: Offices of the Studio: Vol. II: 1894: p. 138 (photograph appears on p. 139)

2. “He was, as an irreverent American once said of him, that “rara avis in human kind,—a poet with money,” and so stole time from his verse-making to give charming little dinners, the lists of which were redolent with Lady This and Countess That, since he knew nearly every woman of title, native or sojourner, in Paris.”: excerpt: Verses Written in Paris by Various Members of a Group of “Intellectuals”: in: The Critic: An Illustrated Monthly Review of Literature, Art and Life: New Rochelle, New York: Vol. XXXIX: 1901: pp. 38-39

3. notes: Ernest Dowson Collected Poems: edited by R.K.R. Thornton: University of Birmingham Press: 2003: pp. 257-258

4. included in: The Poems of Ernest Dowson: Dodd, Mead and Company: New York: 1922: pp. 144-145