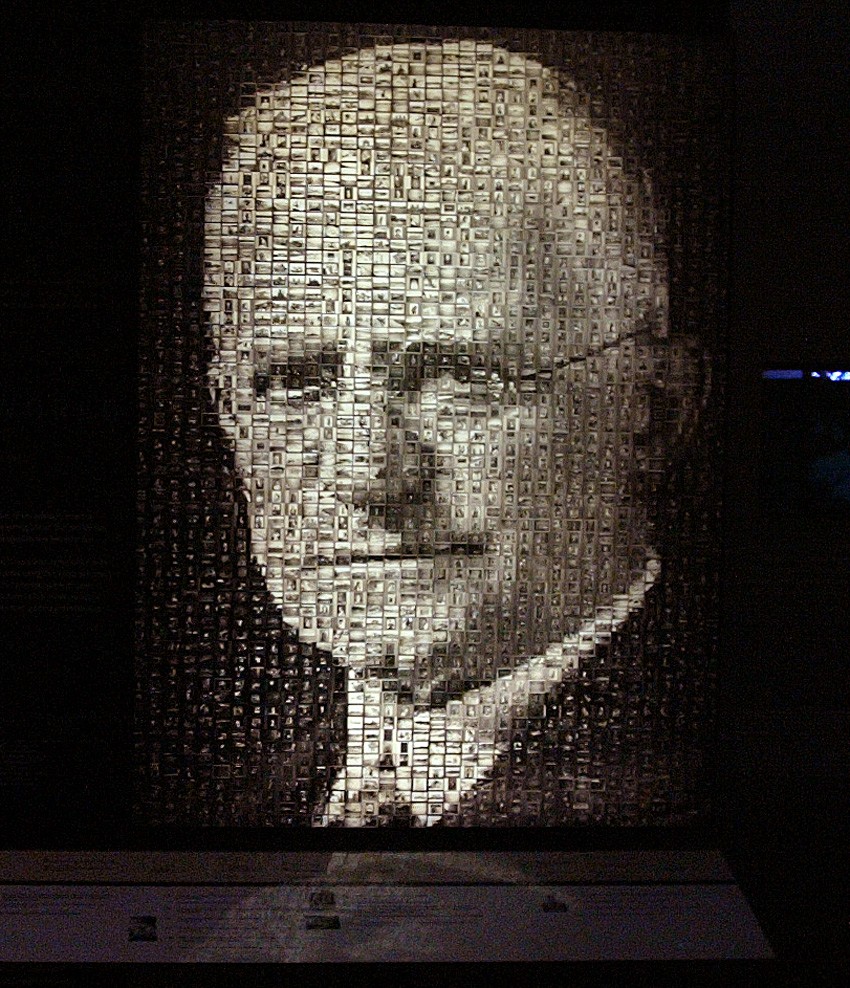

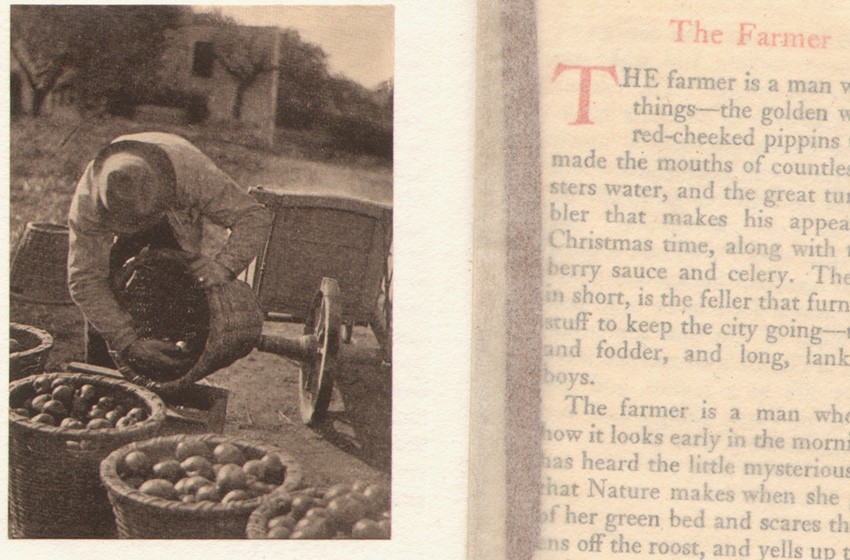

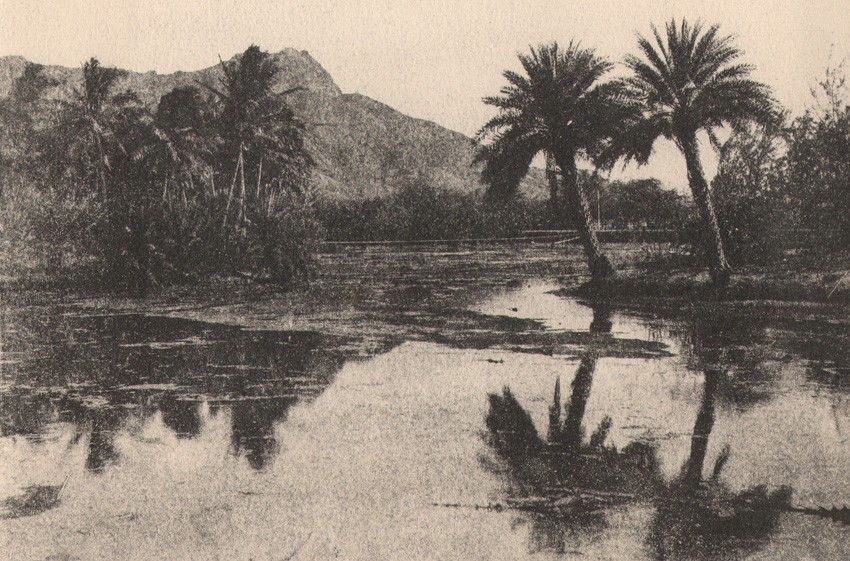

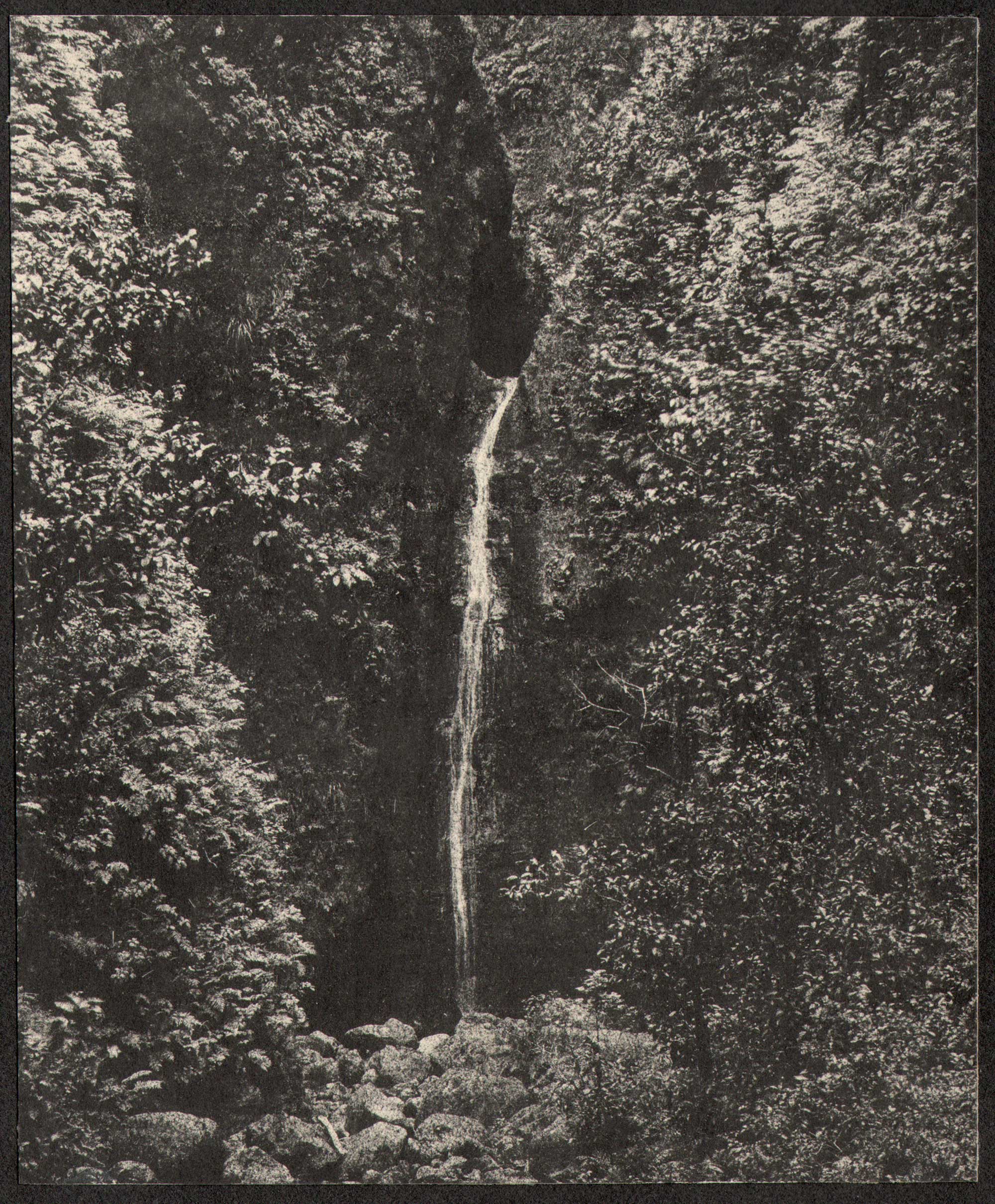

“Sacred Falls : Oahu” (19.0 x 15.6 cm) Believed to be by William Worden, American: 1868-1946: Vintage gum bichromate photograph circa 1900-1910 included with portfolio: “Hawaiian Landscape | Japanese Garden Album “. From: PhotoSeed Archive

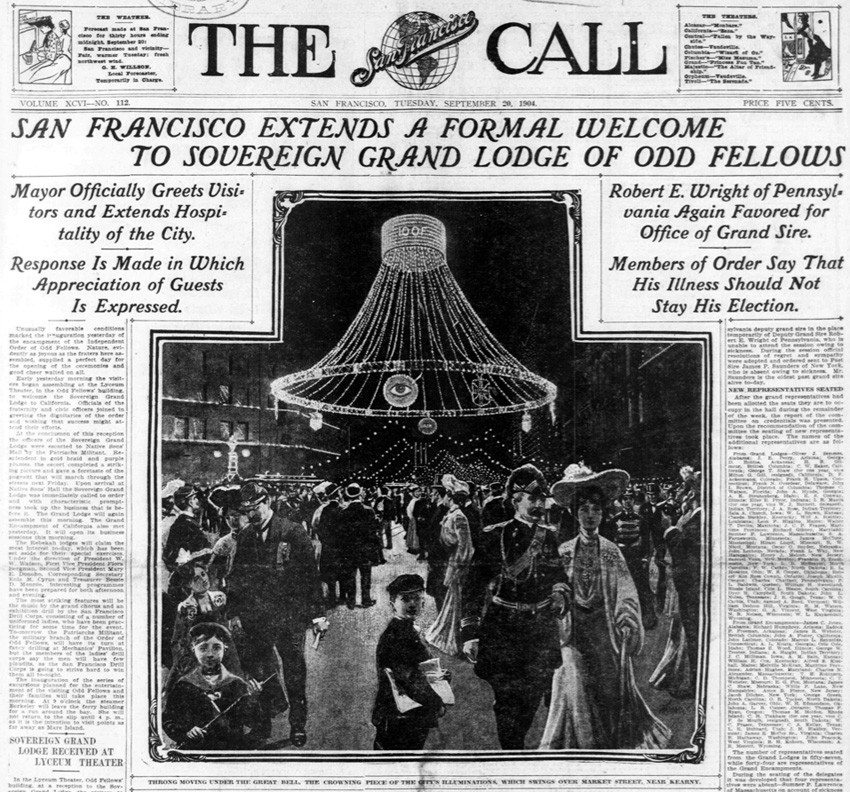

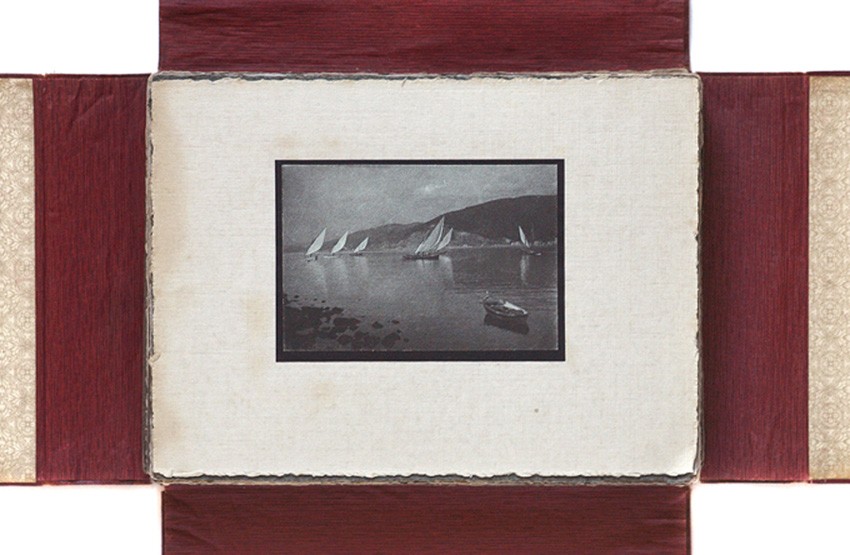

This collection of 32 mounted gum bichromate photographs showing the beauty of the Hawaiian islands circa 1900-1910 were believed to have been taken by California photographer William Worden, (1868-1946) based on the final known 1904 image by him of a rain-slicked Market Street “Grand illumination” view which celebrated the encampment of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows that year. More scholarship needs to be done for the Worden attribution, with the following being my original 2012 post for the album.

You can see all of the album photographs here, as well as my post from 2011.

Album Particulars

The majority of the photographs are believed to have been taken in Hawaii, (known as the Hawaiian Territory at the time) although one photograph, the last presented with the album, shows a nighttime view of Market street in San Francisco, California. Based on other surviving photographs from this era, it depicts the Grand illumination of Market which took place in conjunction with the Sovereign Grand Lodge of the United States and Canadian encampment of Independent Order of Odd Fellows which officially took place in that city from September 19-24, 1904. (1.) Another photograph, appropriately printed in a green tint, shows a stand of Redwood trees, probably taken in California. One subtle clue from the album indicates the photographer may have been a member of the U.S. military based in Honolulu between 1900 and 1920.

The curious and intriguing evidence for this is one of the album leaf supports. On it is a mounted photograph showing the famous volcanic tuff cone Diamond Head on the Hawaiian island of Oahu. On the verso is printed:

War Department

| Headquarters Hawaiian Department |

Honolulu, H.T.

| ——————————-

Official Business

Evidently a mailing envelope, a red ink stamp is used to address its recipient, which is unfortunately mostly rubbed out, except for a few details which can still be gleaned:

Commanding Officer |

Th

| Honolulu

In trying to date this envelope, we note the term Hawaiian Department in relation to the U.S. military did not come into general use until February 15, 1913, when it superseded the term Department of Hawaii. 2.

Taking this further, but of course with no evidence he was the album’s photographer, cursory research turns up a listing for the Commanding Officer, Major Thomas J. Smith, who around this time headed up the Hawaii Ordnance Depot for the U.S. Army in Honolulu in 1917. 3.

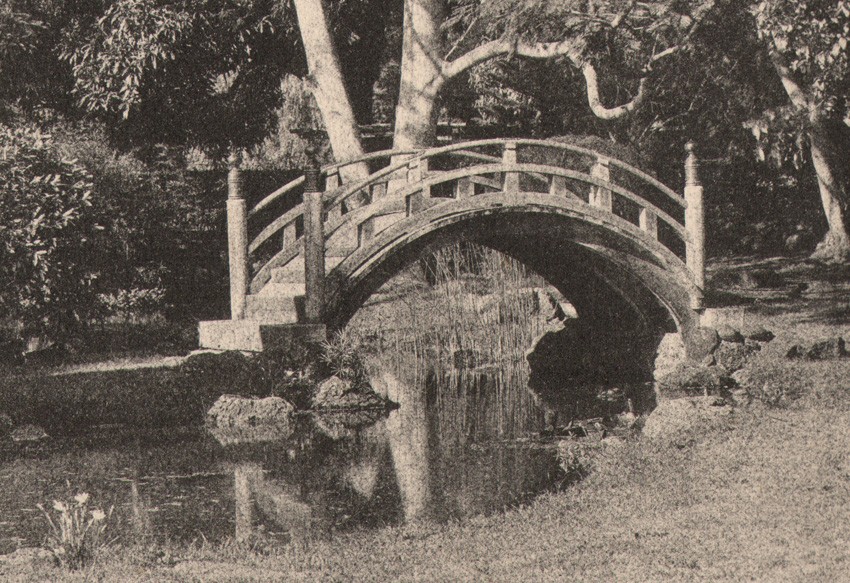

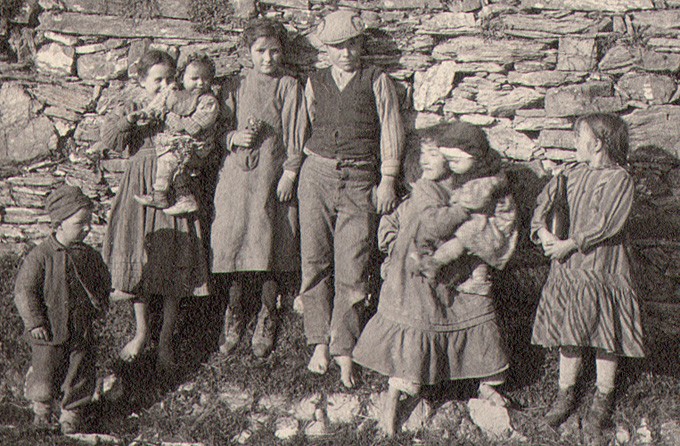

Other than the tell-tale geologic profile of Diamond Head which can be seen in several landscapes in the album, other identified locations for photographs include Moanalua Park and Sacred Falls on the island of Oahu. The present-day Liliuokalani Park and Gardens on Hawaii Island and Foster Botanical Garden in Honolulu-all places existing in the first decade of the 20th century, may be the location for other album photographs. Of course, with the inclusion of the Market street photograph, the well known Japanese tea garden in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park cannot be ruled out as a possible location as well. Among the carefully composed studies, album photographs show Japanese gardens, an interior study of a tea house, a wooden footbridge, stone lanterns, and large Poinciana tree. Other studies include a rice paddy, taro patch and still life of a vase of Sun-lit flowers.

Surviving examples of Hawaiian artistic photography from the period before World War I or earlier not purely topographical in nature are considered rare. But that is not to say there wasn’t an interest in amateur photography in the Hawaiian Islands at this time. In 1889, the well-known photographer Christian Jacob Hedemann (1852–1932) became president of a group of amateur photographers who founded the Hawaiian Camera Club in Honolulu that year. The Photographic Times reported:

“There are about fifty amateurs in the Hawaiian Islands, which ought to be enough material to make the organization prosperous and useful. The public has an interest in it, as one function assumed by the Camera Club is the holding of exhibitions.” 4.

Later, in 1907, the newly formed Hawaiian Photographic Society was also founded:

“The Hawaiian Photographic Society was formed at Honolulu, H. T., in May, most of the enthusiastic amateurs of that city being present to aid in its formation. A notable work to be undertaken by the society is the securing of photographs of the places of historic interest on the island and placing these in the Hall of Archives as the basis for a photographic survey.” 5.

On a provenance note, the album was purchased in 2011 from a former owner in the Midwestern United States. Additional insight into this album is welcomed.

NOTES:

1. CALIFORNIA HISTORIAN JOHN T. FREEMAN: EMAIL CORRESPONDENCE WITH PHOTOSEED SITE OWNER ALONG WITH CORROBORATION OF FRONT PAGE ARTICLES AND GRAPHICS FROM THE SAN FRANCISCO CALL NEWSPAPER EDITIONS OF SEPTEMBER 19-20, 1904 AS RETRIEVED VIA THE CALIFORNIA DIGITAL NEWSPAPER COLLECTION: JANUARY, 2012 2. FROM: WAR DEPARTMENT- ANNUAL REPORTS, 1913: WASHINGTON: GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE: 1914: P. 95 3. FROM: HAWAIIAN ALMANAC AND YEARBOOK FOR 1918: THOMAS G. THRUM: COMPILER AND PUBLISHER: HONOLULU: 1917: P. 169 4. THE PHOTOGRAPHIC TIMES AND AMERICAN PHOTOGRAPHER: W.I. ADAMS, EDITOR: THE PHOTOGRAPHIC TIMES PUBLISHING ASSOCIATION: NEW YORK: FEBRUARY 8, 1889: P. 74 5. NOTES AND COMMENT: IN: THE PHOTO-MINIATURE: EDITED BY JOHN A. TENNANT: VOLUME 7, APRIL, 1907: P. 408