Pictures of East Anglian Life

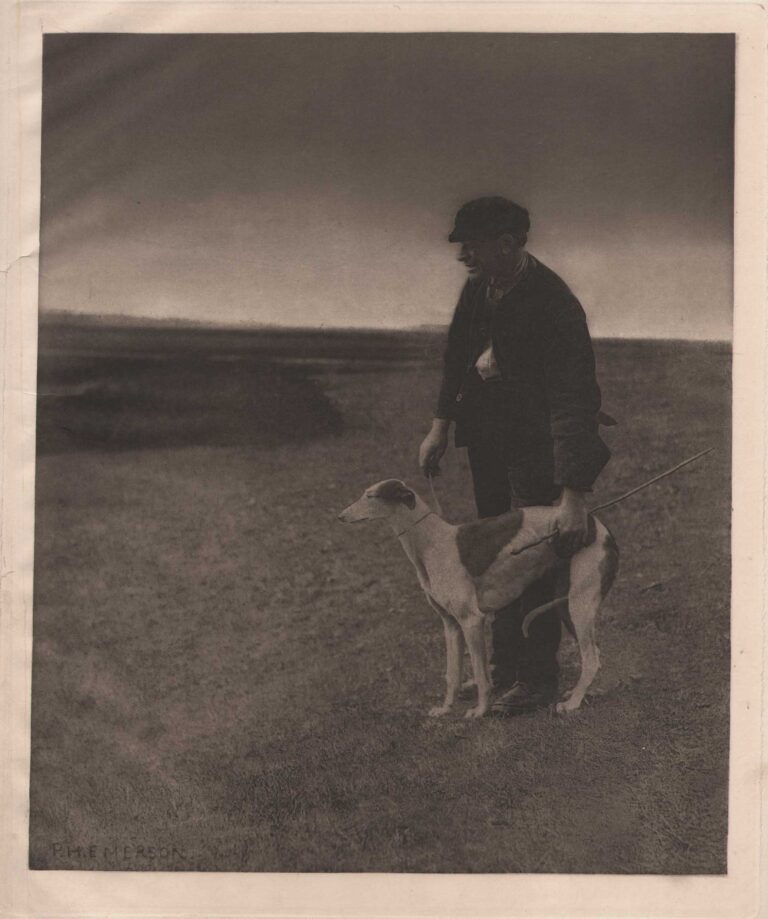

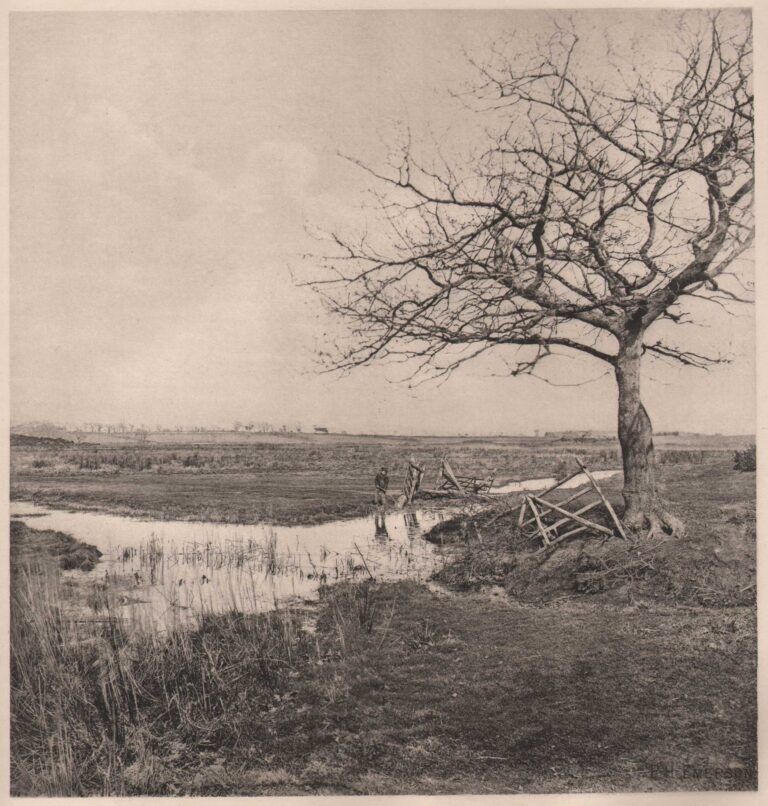

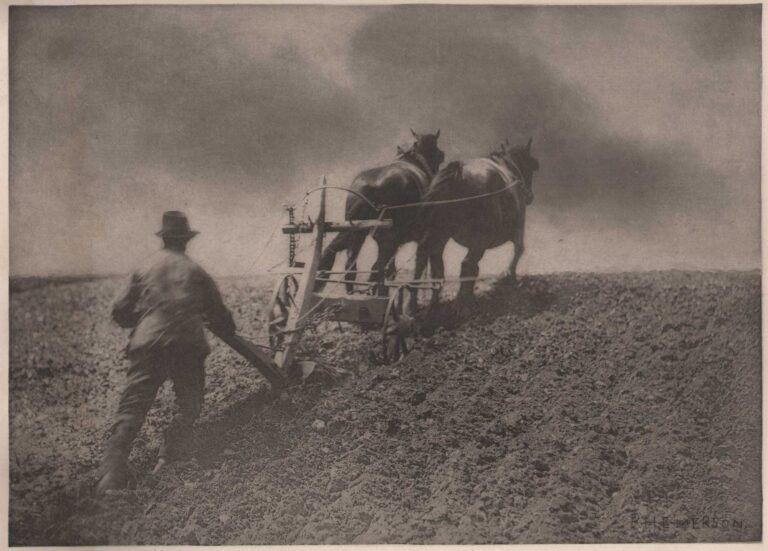

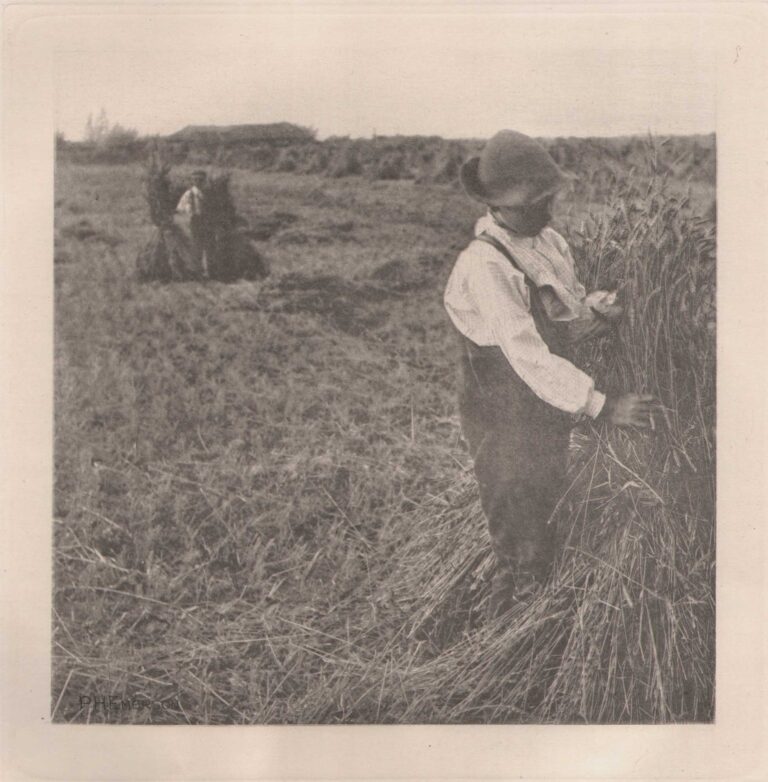

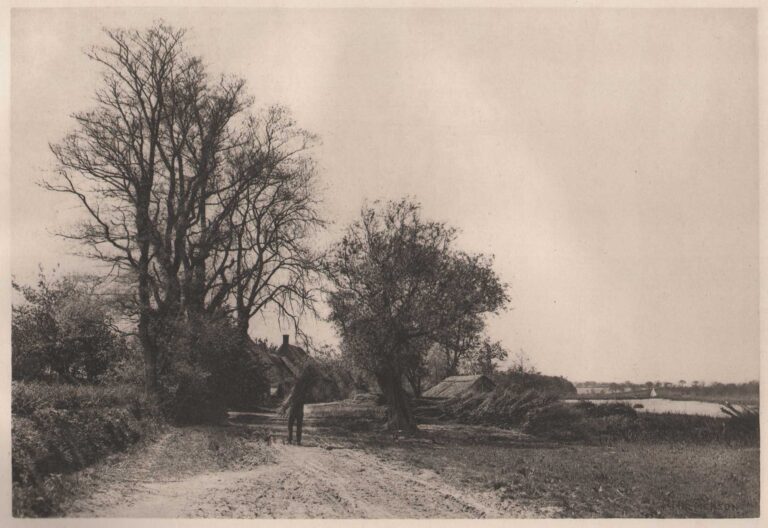

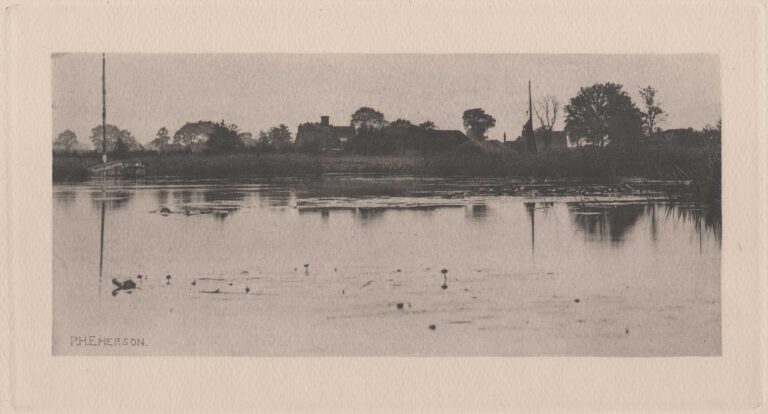

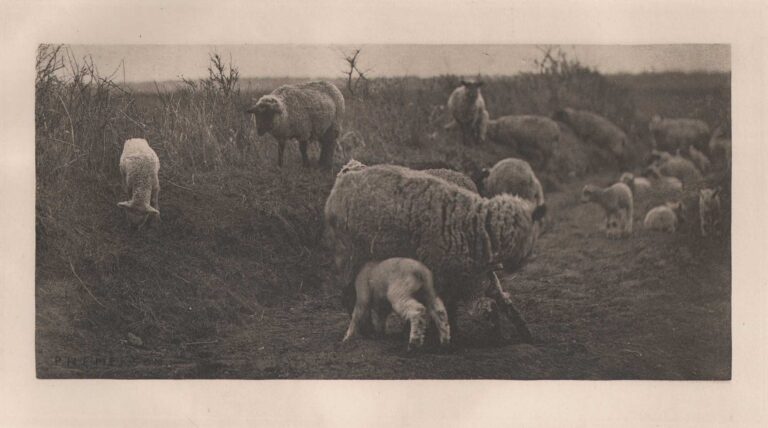

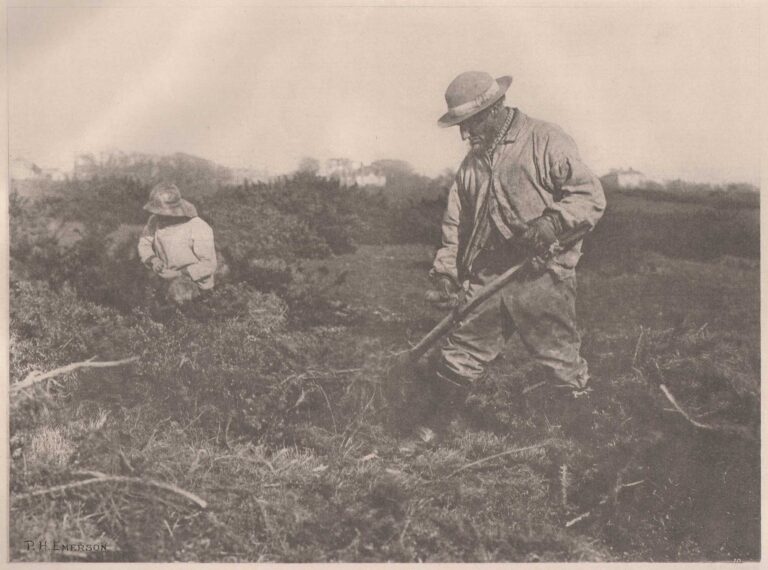

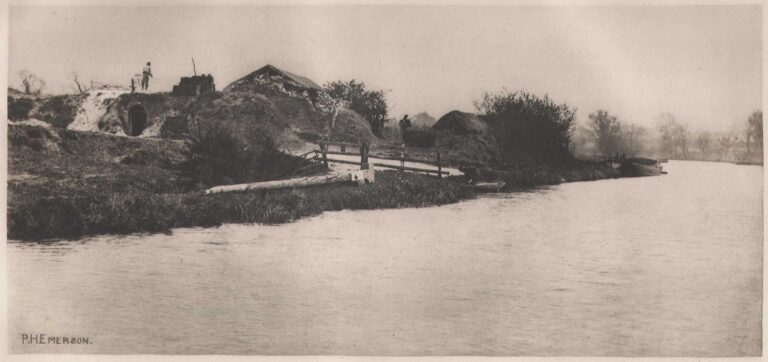

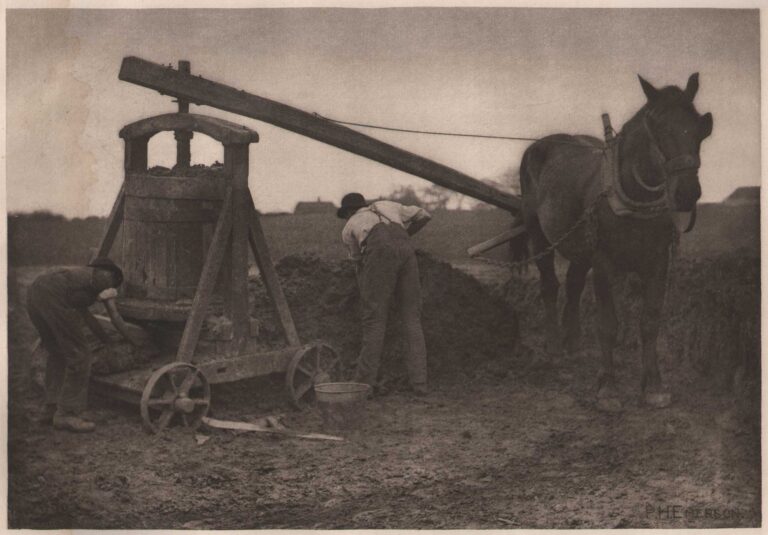

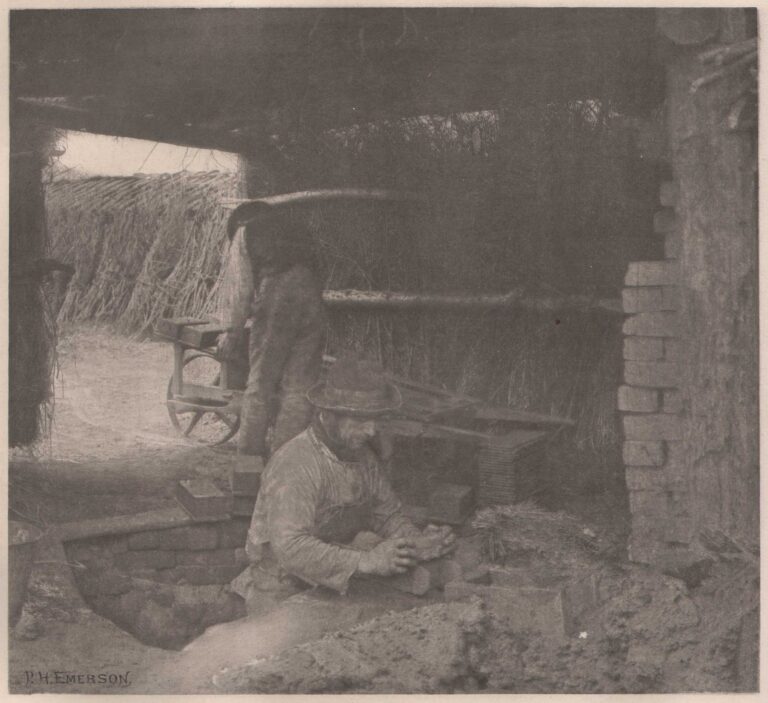

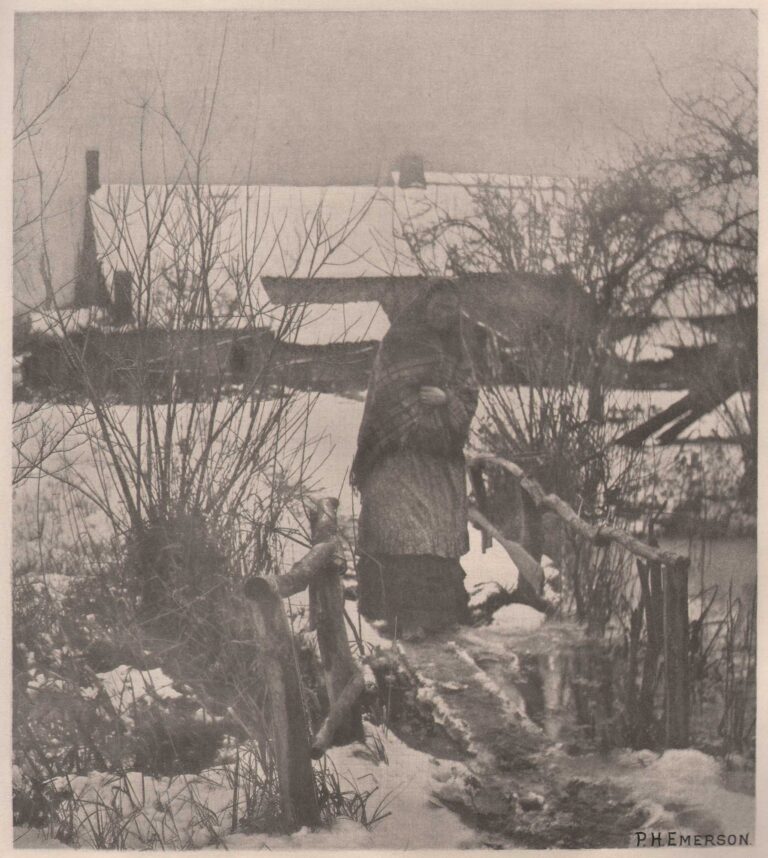

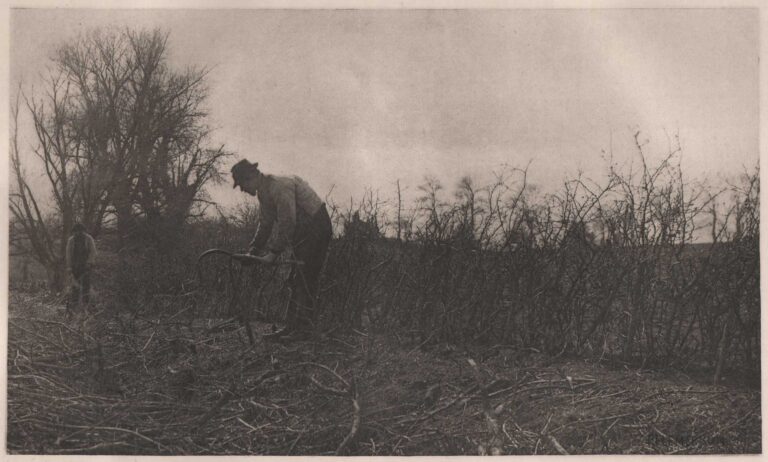

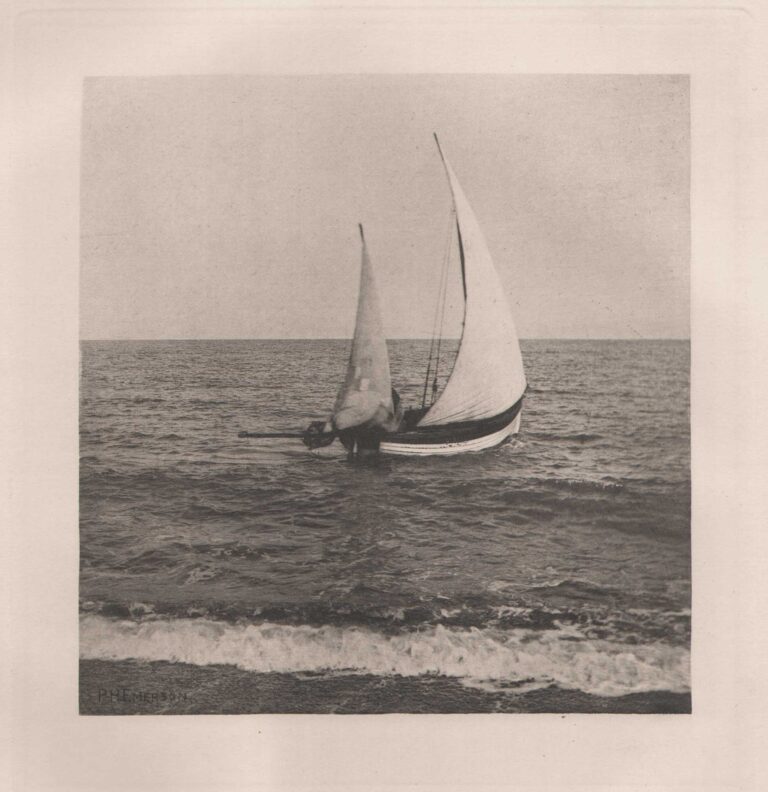

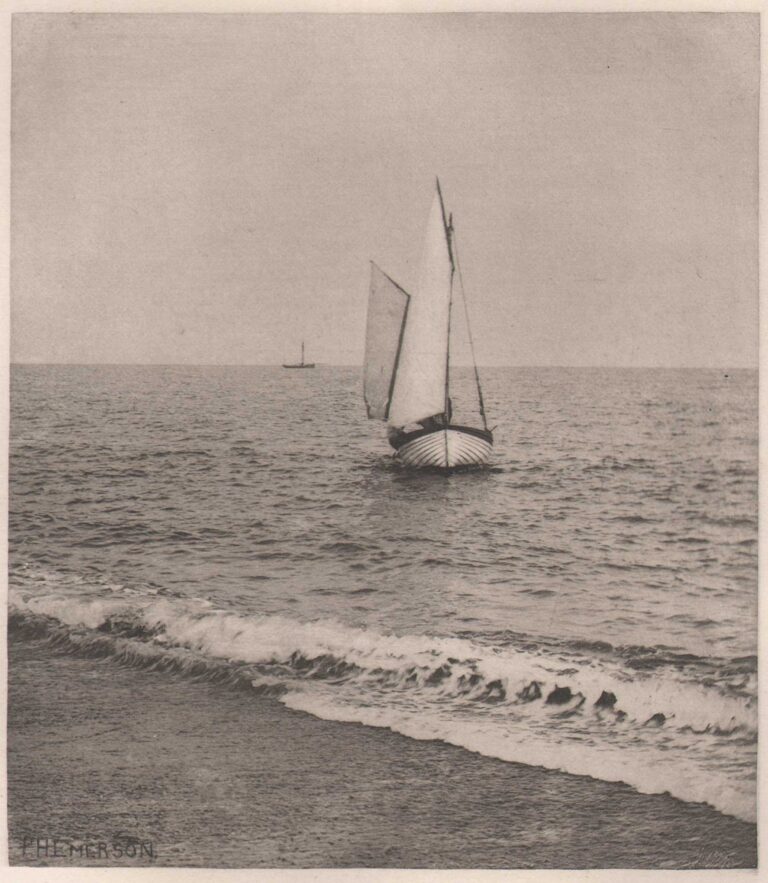

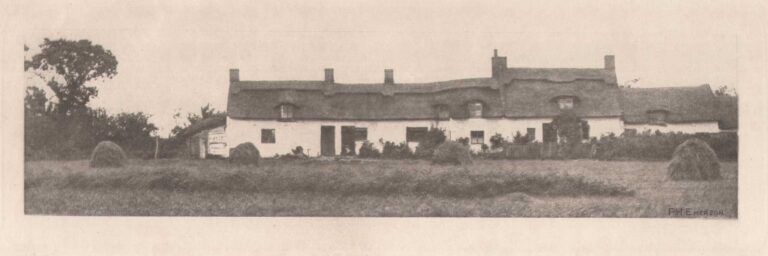

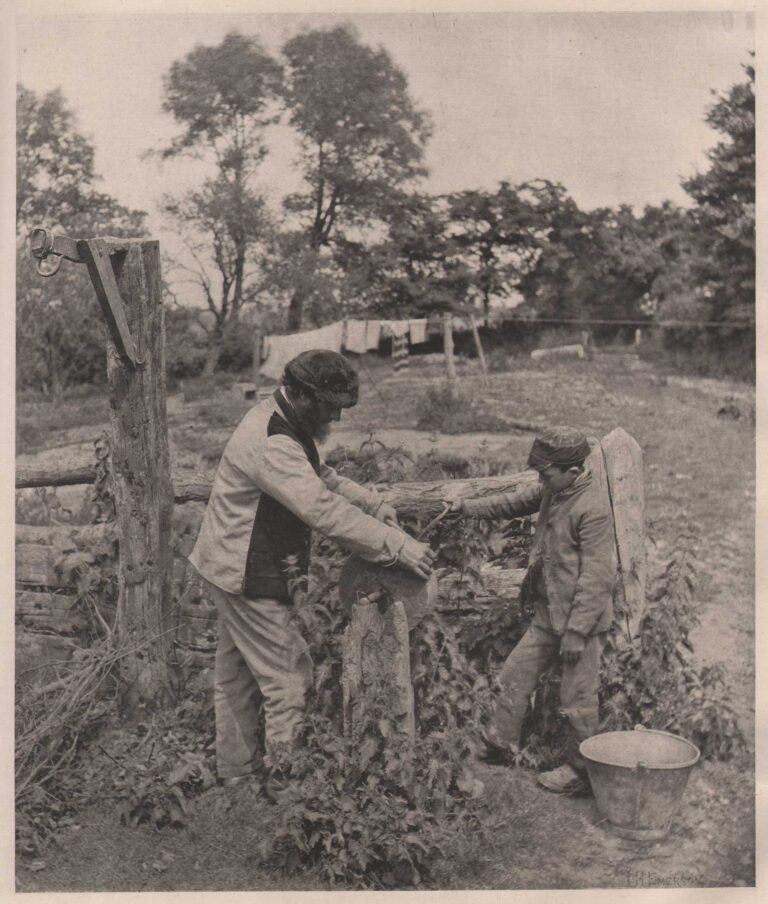

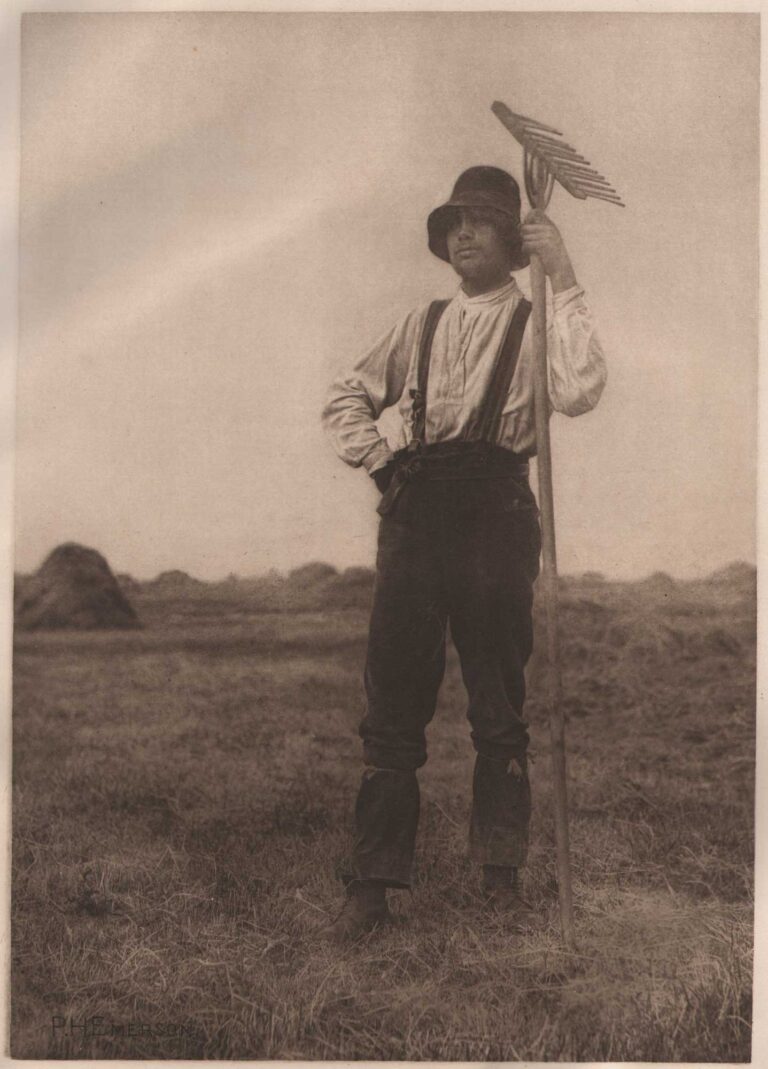

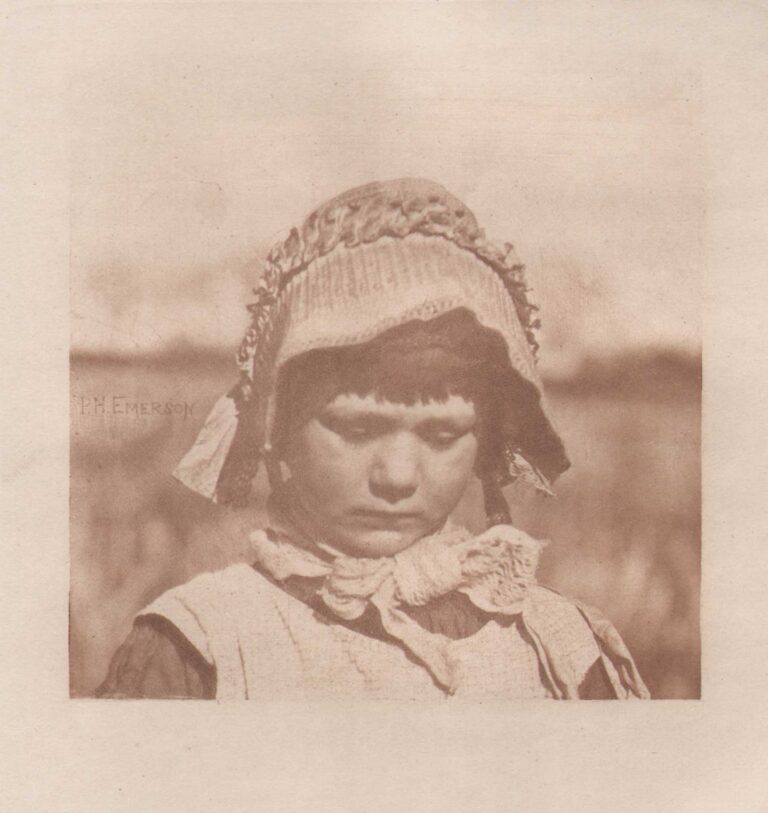

“My aim has been to produce truthful pictures of East Anglian Peasant and Fisherfolk Life, and of the landscape in which such life is lived.” — P. H. Emerson, 1887

The above quote by Peter Henry Emerson, (1856-1936) the British artist most associated with the photographic movement of Naturalism, appeared in the Preface to his 1888 volume Pictures of East Anglian Life. Photo critic Bill Jay, writing in 1970, describes the artist as “the first English photographer to work out a theory of naturalistic photography. His attitude and philosophy had a profound effect on the growth of good photography – he was a mainstream man when his colleagues were stagnating in backwaters“.

But exactly what is naturalistic photography? Straight photography for the most part, the sister to the art aesthetic of Realism, but for our purposes, a lost aesthetic: something that can be defined literally but which technology has forever disrupted. Initially, Emerson was influenced by naturalistic French painting, but eventually soured on his early “straight” photographs as a response- principally his platinum photographs published in his first book, the 1886 volume Life and Landscape on the Norfolk Broads. Eventually he adopted his own soft-focus aesthetic that involved selective, or “differential” optical focus to achieve his aims: “Before long, however, he became dissatisfied with rendering everything in sharp focus, considering that the undiscriminating emphasis it gave to all objects was unlike the way the human eye saw the world.” (2.)

In our modern age, where iPhone cameras combined with basic computer proficiency can create almost any photographic effect, the only hindrance to creativity is our own imaginations. But those were only dreams in the 19th Century, with theories and evolving advancements in cameras and optics the only way to achieve desired results on a photographic plate.

Foundational Work: Pictures of East Anglian Life, 1888

Let’s revisit Emerson’s Preface for this 1888 work: “I have endeavoured in the plates to express sympathetically various phases of peasant and fisherfolk life and landscape which have appealed to me in Nature by their sentiment or poetry. In short, I trust the complete work may form a humble contribution to a Natural History of the English Peasantry and Fisherfolk.”

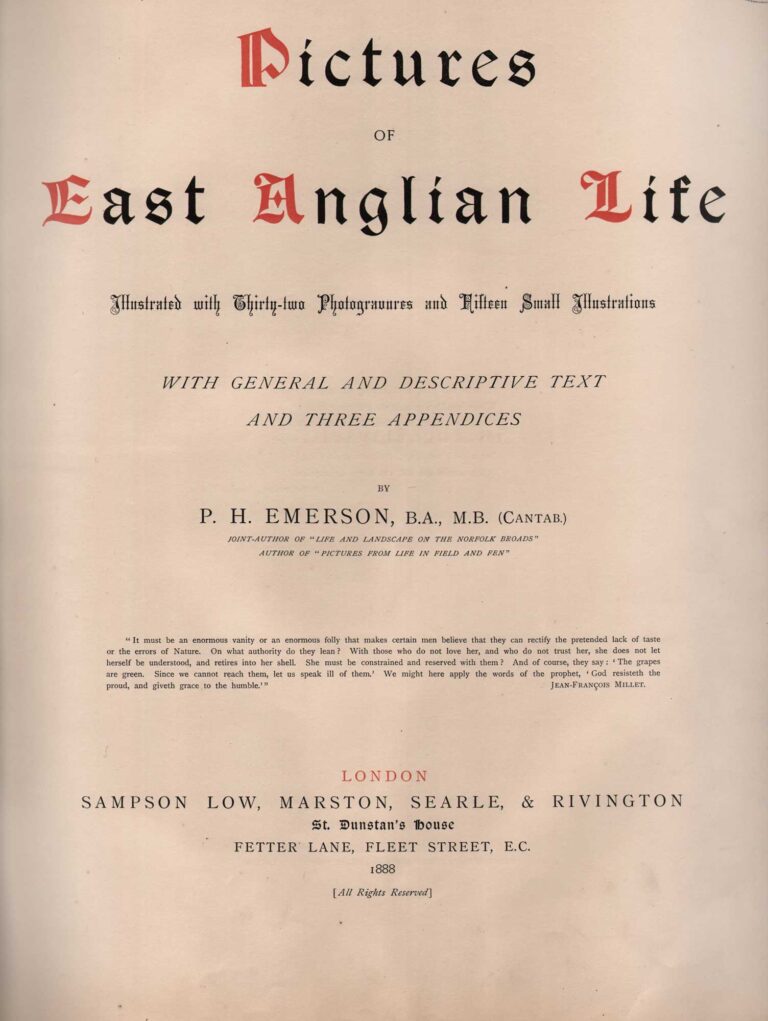

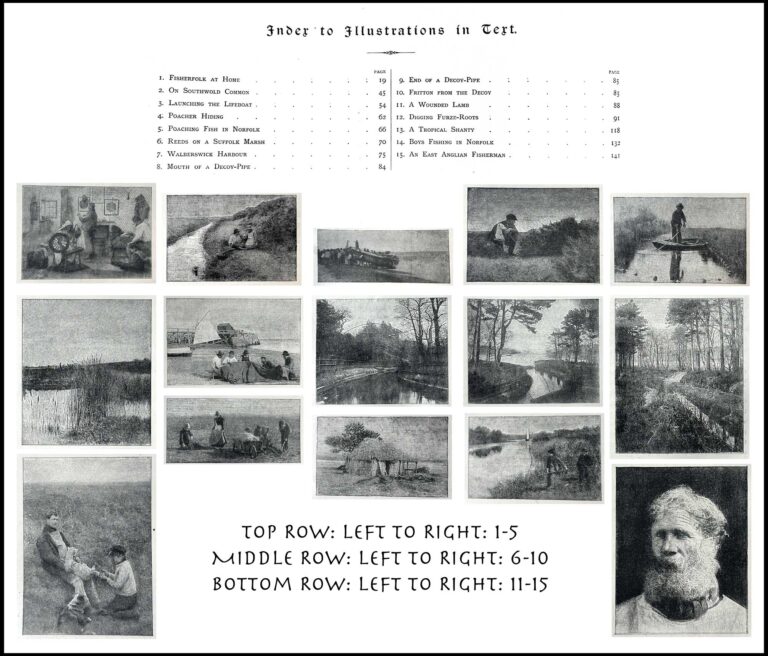

Featuring 32 hand-pulled copper photogravure plates and additional 15 typogravure images printed within the letterpress using the grain Autotype halftone screen, Pictures of East Anglian Life was a showcase for the relatively new photo-mechanical process of hand-pulled photogravure, an intaglio process. It is the largest and considered most ambitious of the artist’s photography books. (1.) A foundational work in the history of Photography, many of the photographs in this superb folio were taken between 1886-87, with the majority copyright-registered at London’s Stationers’ Hall before publication. Many of the artists works were transferred to The National Archives in Kew, (London) with 111 examples accessible—albeit without digital captures of these photographs— online as of this writing.

An early work, from 1885, is “A Stiff Pull“. Originally a silver medal-winning albumen print that year, its corresponding gravure plate published in 1888 (plate IV) eliminated trees via the etcher’s needle which appeared on the right-side of the horizon. Artist Thomas Frederick Goodall, 1856-1944 a good friend of Emerson, additionally made a woodcut engraving based on the work as the folio’s cover illustration .

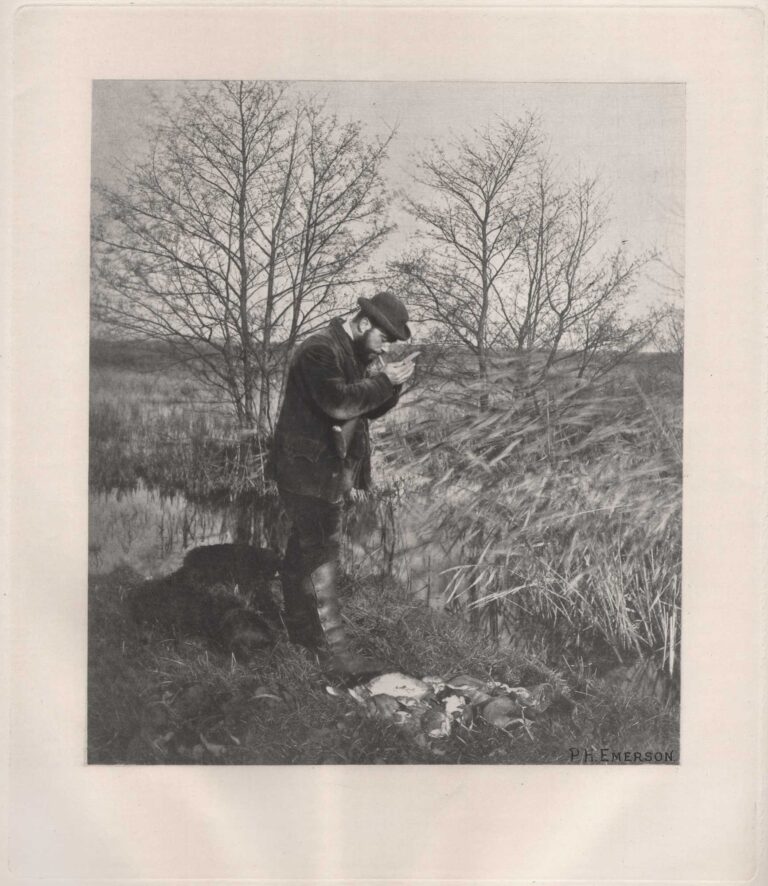

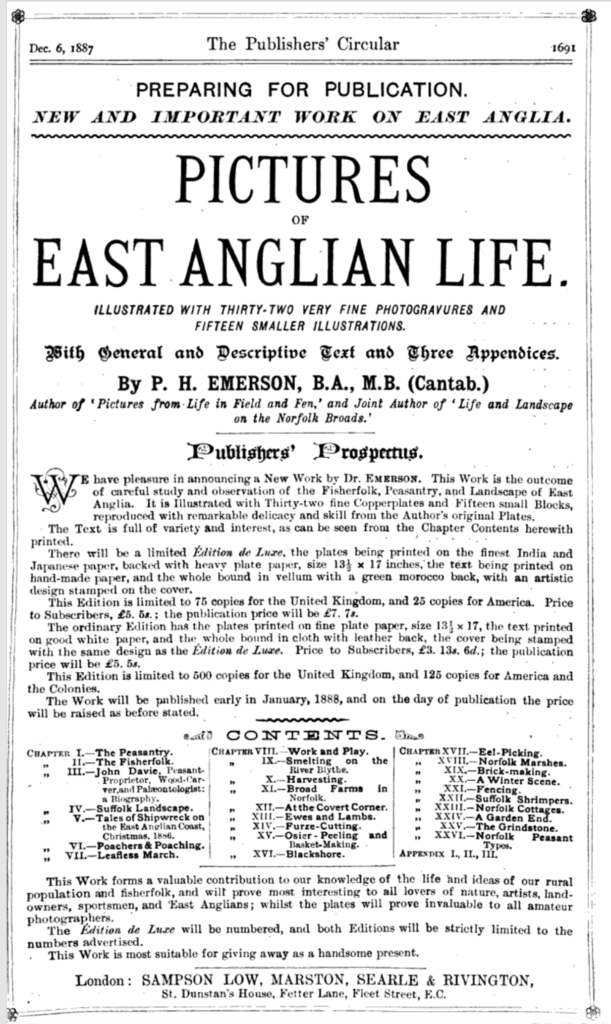

Other examples from 1885 appear as gravure plates in the folio. “The Grindstone”, copyrighted in 1885, appears as this title under chapter heading XXV in a 1887 Publishers’ Circular prospectus advertisement. The name changed however, to “At the Grindstone— A Suffolk Farmyard”, (plate XXX) when published. The artist did another series of poaching images registered in late January, 1886: “The Poacher No. 1-3“, so its possible plate II from the work: “The Poacher—A Hare in View”, may be from this period. A gamekeeper and not a poacher—the distinction made clear by the artist himself—is represented by his picture: “At the Covert Corner”, (plate XI) also taken around this time, registered in late February, 1886.

To add emphasis of the importance Emerson assigned his work, the Preface concludes: “For greater security, each plate in this work has been separately copyrighted; and for the benefit of certain prejudiced persons who are prone to believe all things photographic will fade, I hereby assure them that these pictures will last as long as any etching or engraving.”

A doctor by training, according to the Encyclopedia Britannica: “Emerson soon became convinced that photography was a medium of artistic expression superior to all other black-and-white graphic media because it reproduces the light, tones, and textures of nature with unrivaled fidelity. He was repelled by the contemporary fashion for composite photographs, which imitated sentimental genre paintings. In his handbook Naturalistic Photography (1889), he outlined a system of aesthetics. He decreed that a photograph should be direct and simple and show real people in their own environment, not costumed models posed before fake backdrops or other such predetermined formulas.”

Prospectus advertisement for Pictures of East Anglian Life, as it appeared in The Publishers’ Circular on December 6, 1887. Credit: University of Wisconsin Library, via Google Books.

Publishing & Limitation History

In October 1887, writing from his home in London’s Bedford Park, Chiswick, the Preface concludes, noting the “plates have been reproduced on copper from my original negatives by the Autotype Company, the Typographic-Etching Company, and Messrs. Walker & Boutall, to all of whom I owe sincere thanks for the trouble bestowed on the plates. These plates are, with one or two exceptions, untouched, so that they may be relied upon as true to Nature. Of these plates, the Autotype Company reproduced Nos. 6, 8, 11, 13, 14, 15 17, 19, 22, 23, 28, 30, and 32. The Typographic- Etching Company reproduced the Frontispiece, and Nos. 2, 4, 5, 7, 9, 10, 12, 16, 18, 20, 21, 24, 25, 26, 27, 29, and 31; and Messrs. Walker & Boutall reproduced No. 3.” Fifteen further illustrations—photographs interspersed in the text—also appear in the folio: “reproduced from my original photographs by the Typographic-Etching Company.”

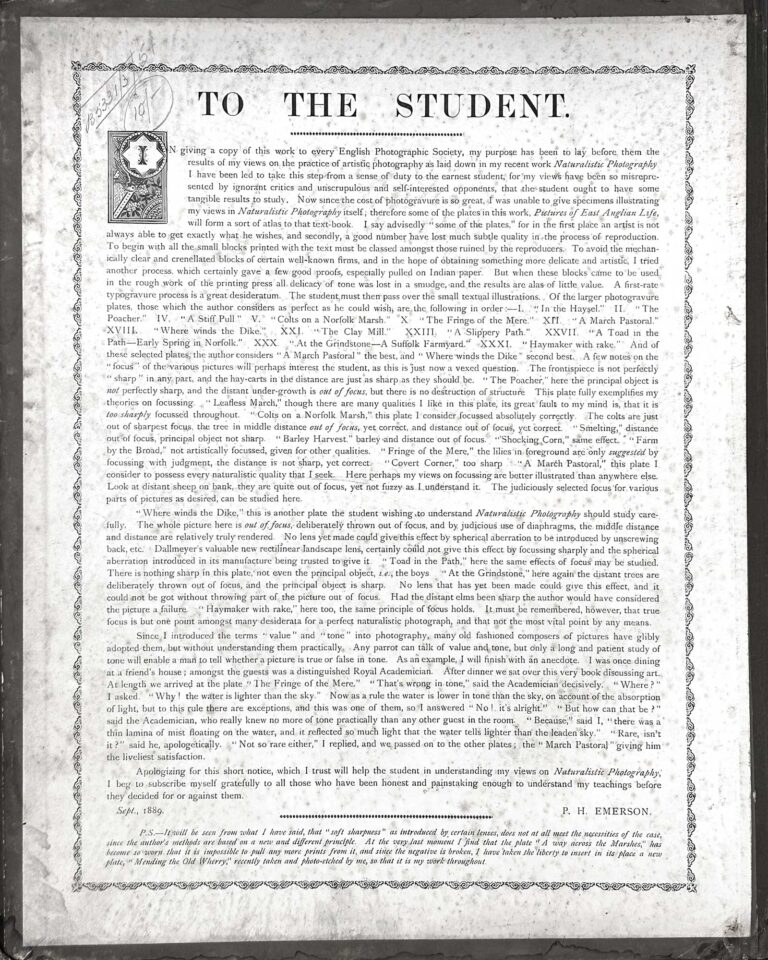

In “To the Student“, pasted to the inside front cover, Emerson further acknowledges his own involvement on a technical level, etching one of his own negatives after a plate had become too worn to print. In fact, although not acknowledged, he was learning the photogravure process from Walter Colls, then associated with the Typographic-Etching Company of London:

“At the very last moment I find that the plate “A way across the Marshes,” has become so worn that it is impossible to pull any more prints from it, and since the negative is broken, I have taken the liberty to insert in its place a new plate, “Mending the Old Wherry,” recently taken and photo-etched by me, so that it is my work throughout.”

Originally, Emerson had intended wider distribution for the work, but high cost involved in production, wear to the plates and limited public interest scaled this back: “The deluxe edition was originally advertised as limited to seventy-five copies, but only twenty-five books and fifty portfolios were actually issued. An ordinary edition bound in half leather was originally advertised as limited to 500 copies, but only 250 copies were actually issued, some with the plate, Mending the Old Wherry substituted for A Way Across the Marshes which wore out after 30 pulls.” (3.)

Contemporary Reviews

Commentary by Amateur photographer William Jerome Harrison, writing in the 1888 edition of The International Annual of Anthony’s Photographic Bulletin, was reprinted in the 1889 edition of the annuals advertising section headlined Dr. Emerson’s Works:

“If anyone wants to convert an artist to photography he should present him with some of Emerson’s pictures; but, whether with this object or otherwise, we earnestly recommend every photographer to obtain and to study Emerson’s works.” Advertising matter continues: “Collectors and librarians should take notice that all of Dr. Emerson’s works are strictly limited to the numbers herein advertised. After completion of the advertised editions all plates and blocks will be at once destroyed. Intending purchasers should therefore complete their sets as eon as possible, before the works become scarce and advance in price. They can be obtained from the publishers direct or through any bookseller.”

In addition to descriptions for Emersons works Life and Landscape on the Norfolk Broads, Pictures from Life in Field and Farm, (sic-Fen) Idyls of the Norfolk Broads and Naturalistic Photography for students of the art, details for this 1888 folio were printed, along with some contemporary press reviews:

PICTURES OF EAST ANGLIAN LIFE. Illustrated with 32 photogravures and 15 blocks, size. 20×16 inches. Edition de luxe bound in vellum with green morocco back, black and gold decorations. Text printed on best English hand-made paper, plates on Indian paper and blocks on Japanese. Limited to 75 numbered copies. Price, £7.7.0. Ordinary edition limited to 500 copies, bound in cloth with leather backs. Plates on fine plate paper. Price, , €5.5.0. (Sampson, Low & Co, Ld., St. Dunstan’s House, Fetter Lane, London, B.C.)

“It is a monograph pictorial and literary,” —Daily News. “Of some of the illustrations it is impossible to speak too highly.” —Graphic. “The volume may be taken, therefore, as representing pretty completely the present state of photo-engraving in England.”—Manchester Guardian. “Dr. Emerson’s new book is one which no county family’s library in Suffolk should be without.” —Pall Mall Gazette. “Splendid photogravures.” —Westminster Review. “The full page plates are often of the highest merit.” —Magazine of Art. “A delightful book.”—Nature. “He is as successful with some of the groups as with the landscapes.” —Academy, &c., &c. (4.)

Further Reading

Stephen Hyde, a noted photographer in the present day, is the great great grandson to P.H. Emerson. Hyde has been a keen observer and honest critic of his famous relation, and provides an important Introductory essay for John Taylors essential volume: The Old Order and The New | P.H. Emerson and Photography 1885-1895. (Prestel-2006) Hydes website has a link to Emerson including a video overview.

- Jeffrey, Ian (2008). How to Read a Photograph. London: Thames & Hudson. pp. 26–27.

- Excerpt: Plate copy for Pictures of East Anglian Life: Photogravure.com accessed November, 2025

- Ibid, November, 2025

- Excerpt: advertisement excerpt: Dr. Emerson’s Works: The International Annual of Anthony’s Photographic Bulletin, June, 1889, p. 38