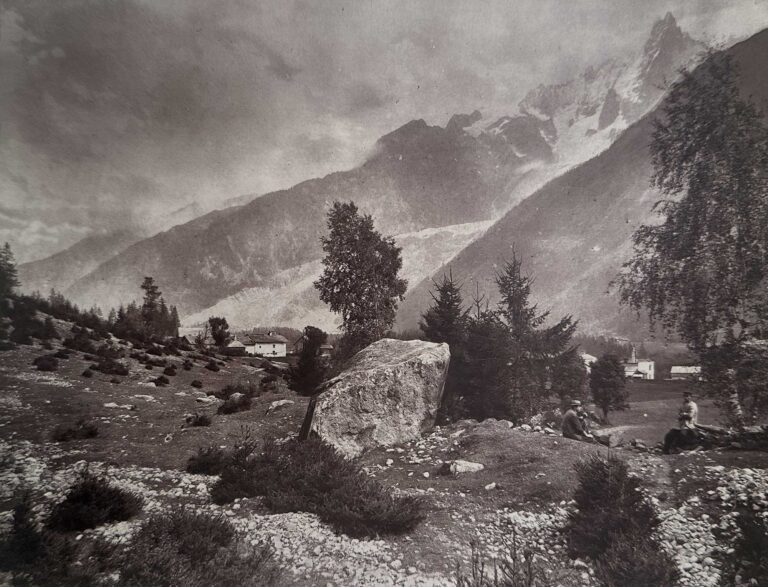

A Church Among the Mountains

Descriptive letterpress printed opposite this photograph:

A CHURCH AMONG THE MOUNTAINS.

GRASMERE Church, in the picturesque graveyard of which rests the poet Wordsworth, has lost in a great measure the loneliness that characterized it when, in 1802, the poet brought home his bride to the pretty cottage of Fox Ghyll hard by, where they resided eight years. To this “dear spot” was addressed the “Farewell:”

“Farewell, thou little nook of mountain ground,

Thou rocky corner in the lowest stair

Of that magnificent temple which doth bound

One side of our whole vale with grandeur rare.”

The side that bound the vale is that seen in the background of our illustration. The cottage referred to, “afterwards for many a year, was mine,” wrote De Quincey. Wordsworth loved to preach in solitary places, and one remembers how beautifully in the “Excursion” he makes ” the churchyard among the mountains,”

“Ridge rising gently by the side of ridge,”

supply the text for some of his noblest teaching, affirming that within the little plot in which these dalesmen slept,

” Not travelling for my theme

Beyond the limits of these humble graves,”

might be found all

“the universal forms

Of human nature.”

-types illustrating every phase of human life, its sin and sorrow, its joy and misery, all that excites love and esteem, or hatred and detestation, as fully as amidst the proudest dust

“That Westminster, for Britain’s glory, holds

Within the bosom of her awful pile,

Ambitiously collected.”

And he made good his position by those well-known poetic descriptions of the lives and lot of the occupants of the quiet graves around him, raising before the mind’s eye,

“Clear images

Of nature’s unambitious underwood,

And flowers that prosper in the shade,”

relating the lowly story of the oppressor and the oppressed; the wrong-doer, and of those “whose sorrow was rather to have suffered wrong”⎯so happier: of him whose life was ruled by the law of gentleness, and of the world-weary man, tired of cities and their vain show, seeking at last the peace that is among the lonely hills, and the healthy, homely dalesman, the patriarch of the vale, the man

“of cheerful yesterdays

And confident to-morrows,”

the poet finally soaring up to the loftiest height, in the grand enunciation of his belief that, whether within the crowded precincts of busy cities or among the mountains,

“Life . .. is energy of love

Divine or human; exercised in pain,

In strife, and tribulation; and ordained,

if so approved and sanctified, to pass,

Through shades and silent rest, to endless joy.”