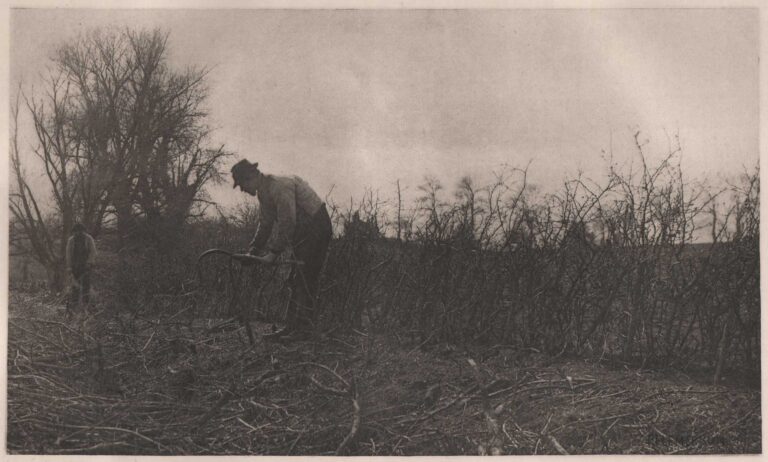

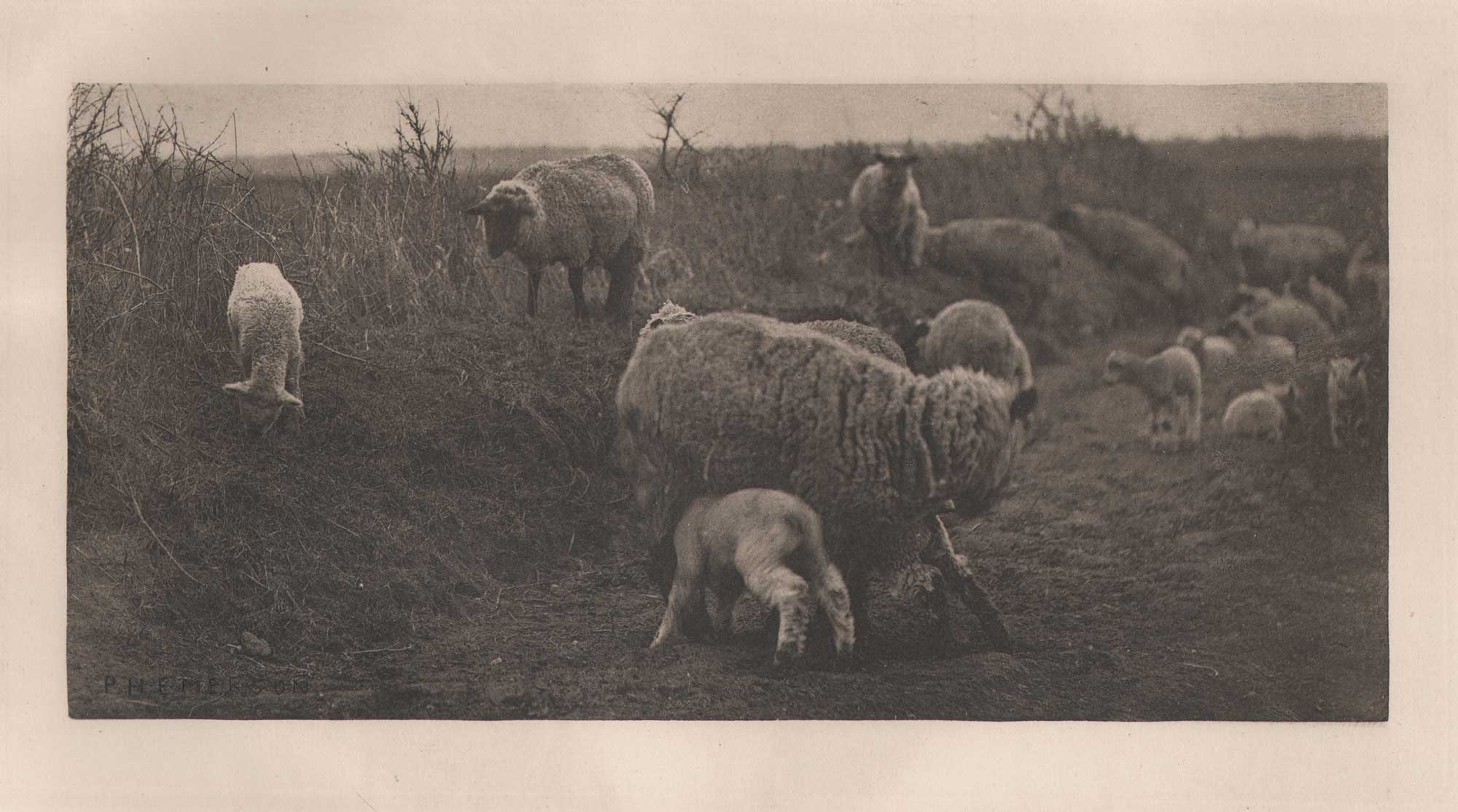

A March Pastoral {Suffolk}

“A March Pastoral,” this plate I consider to possess every naturalistic quality that I seek. Here perhaps my views on focussing are batter illustrated than anywhere else. Look at distant sheep on bank, they are quite out of focus, yet not fuzzy as I understand it. The judiciously selected focus for various parts of pictures as desired, can be studied here.” ⎯ P.H. Emerson, Sept., 1889, To The Student

From Chapter XIII: Ewes and Lambs

“HERE is depicted, in very early spring, the hedgerow of a Suffolk field. The sombre tone well expresses the bleak, raw day of early March. An old ewe occupies the foreground, with her two young lambs tugging at her full udders, thus already beginning the battle of life. On the hedge itself, a lamb of independent character- he is only two or three weeks old-nibbles at the grass. We have read somewhere that in a certain country (India, we think) the cattle-breeders watch for these independent members of the flock and choose them before others for breeding stock. It is as with men; those who huddle together have but little character; original minds always wander from the flock. In the distance of the picture the lambs lie about on the ground, whilst the ewes search about for delicate morsels of new grass or early budding herb. These sheep are not of pure breed, with the exception, perhaps, of the sheep in the hedgerow, which are of the black-faced Suffolk breed. In this county the lambs are born in the cold fields, and in sheep-yards made with hurdles interlaced with gorse. Inside this yard a pen is made by enclosing a smaller space with furze-panelled hurdles, and roofing it in by placing other hurdles across them. The floor is littered with straw. When a ewe drops a lamb, the young creature is picked up by the shepherd, who takes it into the pen, and, by imitating the bleating of the lamb, entices the mother in after him. He places the lamb in the warm straw, and leaves both ewe and lamb there for a few hours. The sheep in the picture are nibbling at grass and turnips, which the shepherd has pulled, and cast along the hedgerow to leeward, so that the sheep can feed and the lambs be protected from the biting north-easterly winds so prevalent in March. The lambs’ tails have been cut, which points to their age being over a fortnight, for it is the practice to cut their tails and geld them at a fortnight old. Lambs born in the end of February and beginning of March will be ready for killing as fat lambs in July or August. Lamb in some parts of England is very dear, commanding from one shilling to fourteen pence a pound retail; but in this, as well as most other supplies, it is the middleman who secures the prize; and in a part of Suffolk in which we once lived, the farmer and butcher could so little agree about prices, that the former took to killing his own lamb and sending it round in carts at eightpence-halfpenny a pound, in that way making more than he could have done had he sold it to the butcher.” p. 87