Aan Den Voet Van Den Cremer-Val (Suriname) | At the foot of the Cremer Valley (Suriname)

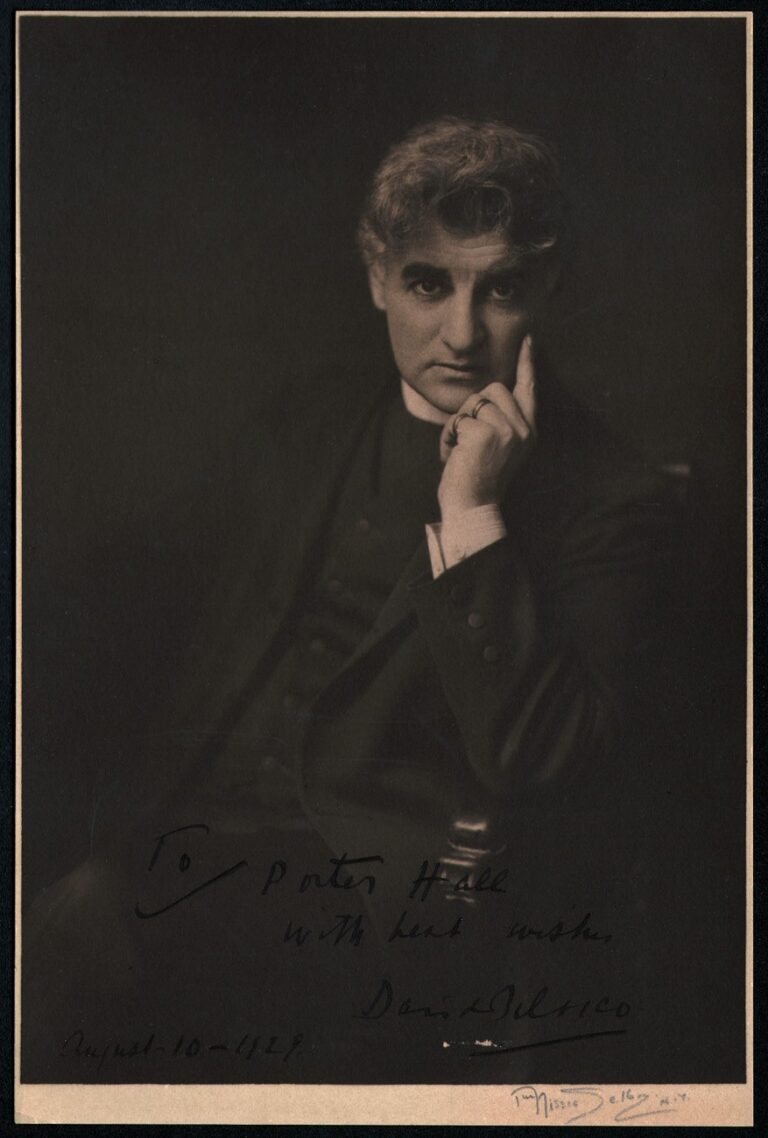

Louis August Bakhuis: 1855-1932

Louis August Bakhuis was a Dutch soldier and explorer who became best known for his expedition to the Coppename area in Suriname in 1901. The Bakhuis Mountains were named after him following this expedition. – Wikipedia

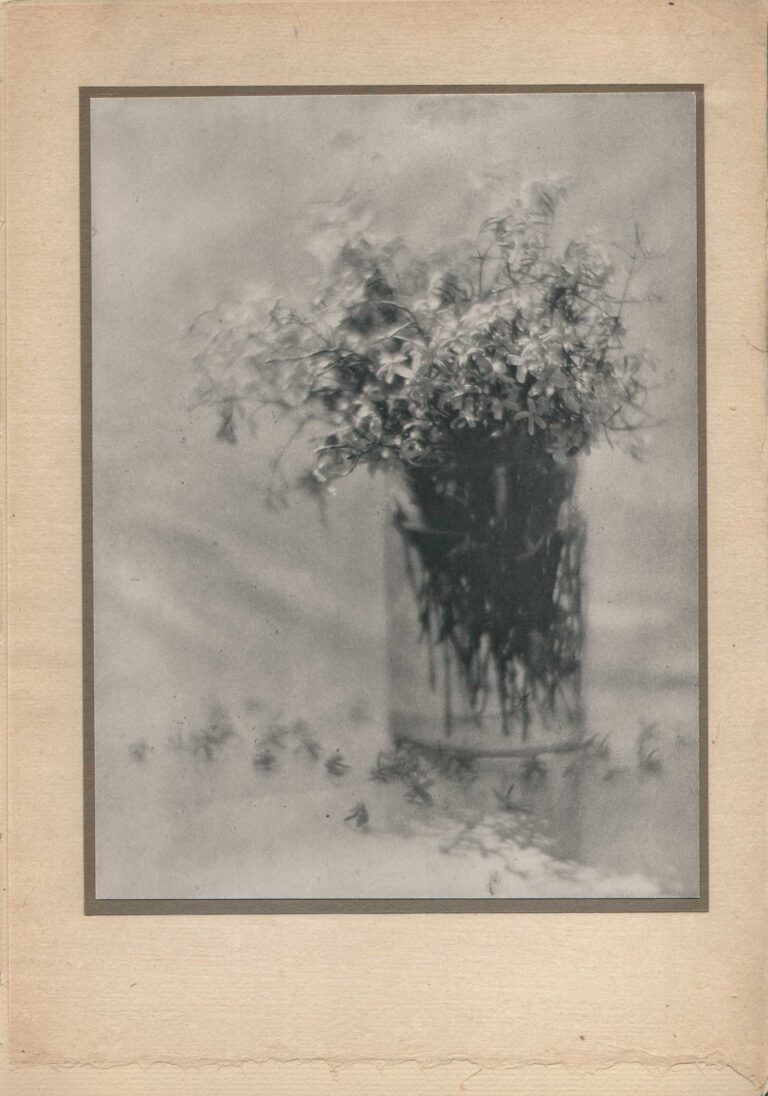

Our heliogravure. (translated)

The image after which our heliogravure was made, is one of the many that Mr. Bakhuis brought with him from the deep wilderness of Suriname, which he visited in 1901, to trace the sources of the Coppename River and to map the river basin, of that river, still completely unknown in its upper reaches.

It gives a view of a gigantic granite dam, which completely blocked a left arm of the river, which was 200 meters wide at the time, except for a channel of five meters, through which the water forced its way with thundering force. The dam rose two meters above the water on the lower side and had a width of thirty meters. In order to be able to continue the exploration of the river, the boat had to be completely unloaded and partly dragged over the rocks. The waterfall formed by this dam was later named Cremer-val, after the former Minister of Colonies J. T. Cremer, who by proposing a subsidy to the States-General had made it possible for the research to take place.

That there are great drawbacks to taking photographs during such trips is also evident from what Mr. Bakhuis reported in his report on his trip in the magazine of the Royal Dutch Geographical Society (1902).

After having established that photography has again proven to be a practical aid in reproducing the impressions gained on the trip, he pointed out, however, that since the tropical climate has such a damaging effect on equipment and plates, the utmost care for one and the other is a necessary requirement in order to return home with usable results. To begin with, the plates were carried in sealed tins, which slid around the original packaging. Originally, the plates were developed in the evenings at the bivouac sites, and a spot in the jungle, out of the glow of the bivouac fires, was chosen for this purpose. Various “bargains” that were experienced in the meantime, such as the falling over of a primitive table and the falling of a tropical rain shower during the development, the shuffling of snakes during the work, but especially the eating away of the gelatin layer by insects during the night, when the negatives were drying, were the reason that the developing was soon stopped during the journey and this was left until after the return to Pattia. Only to occasionally test the light-tightness of the device and to check whether the exposure times were well chosen, a few test plates were developed after that time.

It was now, however, a matter of carefully packing the exposed plates to be too sensitive to atmospheric influences and therefore airtight. The adhesive plaster has proven invaluable services for this. Where there is always a chance that the sensitive skin will suffer from excessive heat when soldering the cans again, there is no need for this when using adhesive plaster. to fear and the treatment is also much simpler.

The plates were placed two by two, with the gelatin layers directly against each other, in the box and this was slid back into the tin box; by sticking a strip of adhesive plaster half over the lid and the tin box, a perfectly airtight seal was obtained.

After returning to the Netherlands, the plates were treated by means of standard development. Thanks to this and to the airtight seal, it is possible to obtain very usable and for the most part beautiful negatives from almost all the recordings.