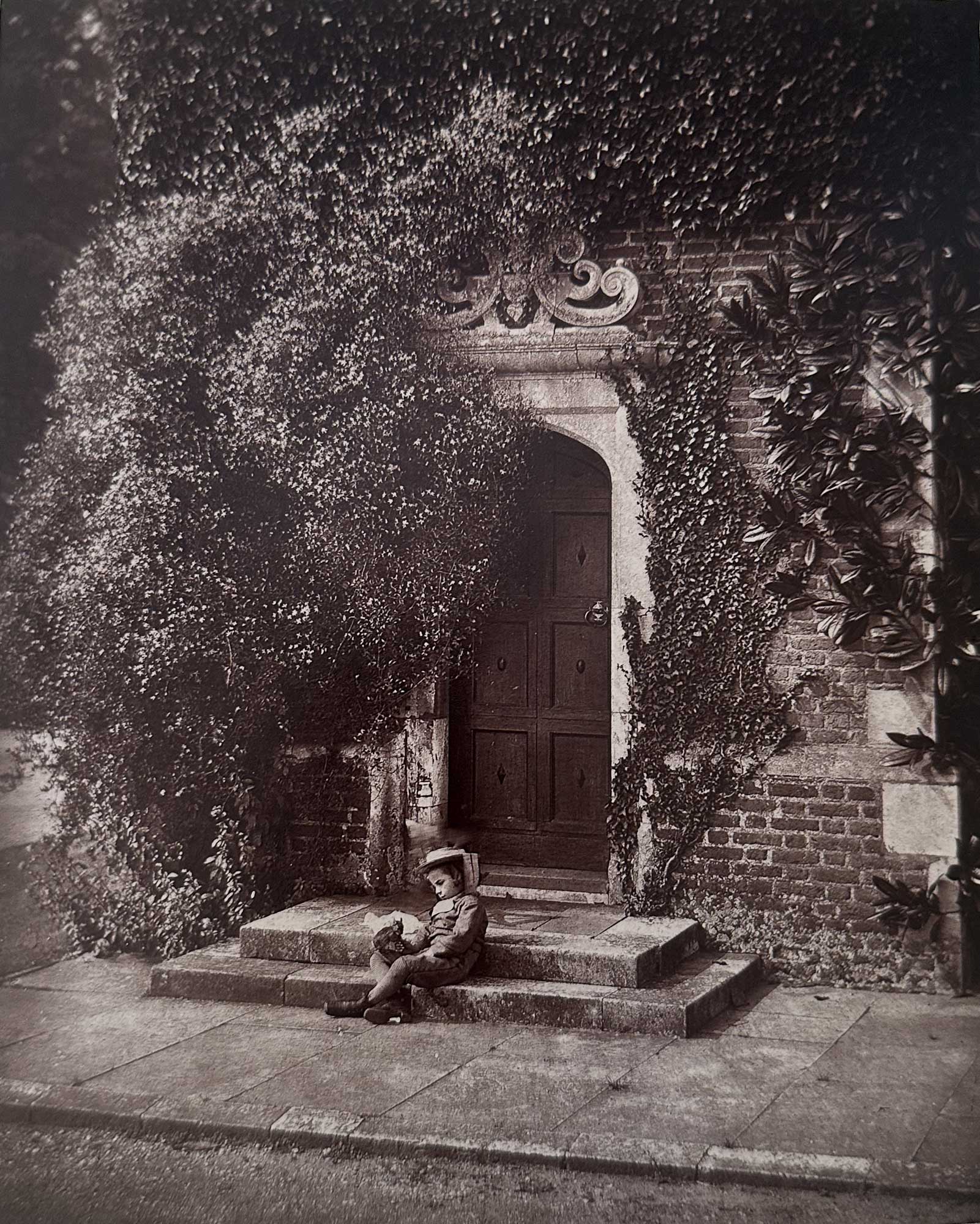

At Hatfield House

Descriptive letterpress printed opposite this photograph:

AT HATFIELD HOUSE.

A JESSAMINE tree in full flower, sweet-scented, and nebulous with white star-like blossoms, mantling the quaintly carved doorway of an Elizabethan house, is always a picturesque object. But at ” Hatfield” one of the most perfect of all the palace-homes erected at that period–it gains additional admiration by its picturesque entourage. Close by is the Elizabethan garden, long avenues of limes forming entirely covered walks around the sides, mulberry-trees planted by James I., stately arched hedges, another garden in the ancient geometrical style of the seventeenth century, a maze belonging to the same period, and beyond them all a vineyard, described by both Evelyn and Pepys in their Diaries. Its associations have been recently revived in Mr. Tennyson’s drama of “Queen Mary.” Here, while seated beneath an ancient oak in the Park (still carefully preserved and fenced in), Elizabeth received the news of the death of her sister Queen Mary, here she held her first Privy Council, and from hence was conducted to the throne she was destined to fill so long-1558-1603. During all this period Hatfield remained in her possession, but at her decease, her successor, James I., exchanged Hatfield for the palace of Theobalds, with Sir Robert Cecil, afterwards Earl of Salisbury.

Much remains of the old palace, inhabited both by the young Edward VI. (who was also conducted hence to the throne), and Queen Elizabeth. The chamber she occupied, with its exterior of dark red brickwork, overgrown with ivy, is still to be seen, and the grand banqueting hall of the old palace, though turned into a noble stable, is impressive still. Therein were kept the Christmas festivals. In 1556, Sir Thomas Pope made at Shrove-tide for the “Ladie Elizabeth, alle at his own costes, a greate and rich maskinge, in the greate hall at Hatfielde, where the pageants were marvelously furnished.” At night the cupboard of the hall was richly garnished with gold and silver vessels, and a “banket of sweete dishes, and after a voide of spices, and a suttletie in thirty spyce, all at the chardges of Sir Thomas Pope.” On the next day was performed the play of Holofernes. The gloomy Queen Mary did not, however, approve of these gay doings for the amusement of her sister Ladie Elizabeth, then in her twenty-third year, and intimated in a letter to Sir Thomas Pope that these “folliries” and “disguisings” must cease.