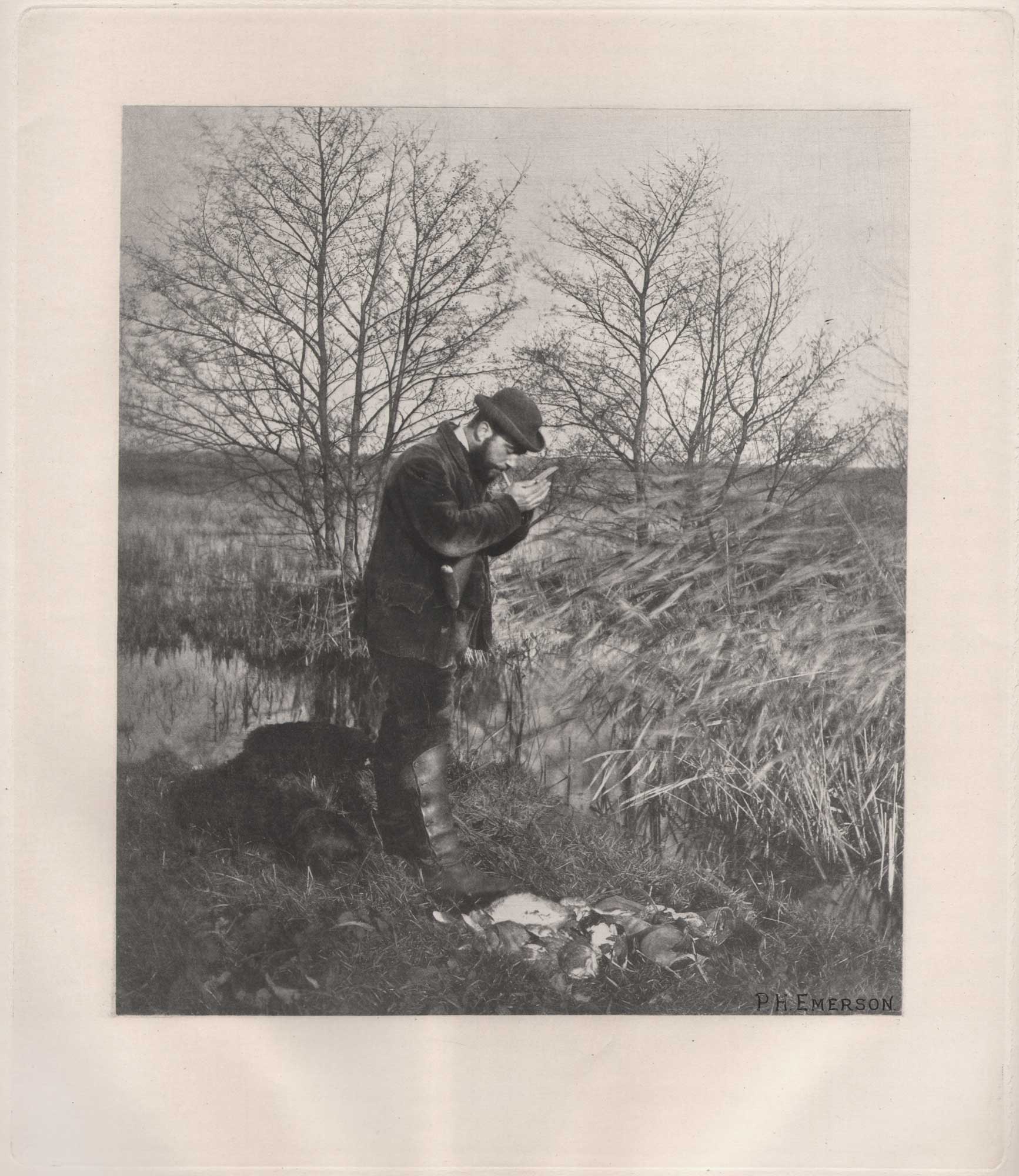

At the Covert Corner {Norfolk}

“Covert Corner,” too sharp” ⎯ P.H. Emerson, Sept., 1889, To The Student

From Chapter XII: At the Covert Corner

“THE morning had broken clear and crisp, the sun sparkled on the delicate veil of hoar-frost which spread over reed-stem and alder-branch. The frozen mud crackled and crunched under foot as the gamekeeper called his two retrievers, and placed one of Greener’s cartridges, loaded with No. 5 shot in his left barrel, and one loaded with No. 8 shot in his right, with an eye to duck and snipe. Lighting his pipe, he slings his gun under his arm, and whistling to his dogs, strides from his cottage home down to the marshes. The keen air sends the blood tingling through his veins and imparts vigour to his step. On he goes, wishing the carter and the shepherd good morning as they pass with their horses and sheep. He leaves the highroad and walks along the marsh, crushing the blades of frozen grass and broken reed which stand out from the ice, when suddenly, turning a corner, he hears a flapping of wings, and a duck, with loud quacking, rises from the broad-edge. Bang goes the left barrel, a few feathers float away on the breeze, and headlong falls the duck into the water as the sulphurous powder-smoke steals away in the clear thin air. With a word to the large retriever, the keeper reloads his barrel, whilst the dog boldly jumps into the cold water, and after swimming a few strokes reaches and gently seizes the mallard, turns and comes back to his master, who relieves him of his burden. Then the dog shakes his shaggy coat, and runs after his master, who is now striding along over the flooded half-frozen marsh, the thin ice cracking and the water gurgling and splashing beneath him. Suddenly from a grassy knoll rises a snipe, uttering its chuckling note, and speeds on its zigzag flight; but the wild-fowler is too quick, and the quiet marsh again resounds with a loud report, which is responded to by the dying “peep peep” of the snipe as it flutters to the ground. The sun rises higher, and the frosty feather-tracery melts; still the keeper strides on, now and then adding to his bag. Over marsh, and along river-walls, and through old reed-beds has he sped, and now at noon we find him in the alder-carrs near home. Here he has been sorting his bag, and deciding what he will do with the birds, how he will take his master the snipe, how he will eat the mallard himself, and how he will give the owl to the village doctor, who is a bird-collector. In the midst of his calculations, however, he decides to have a pipe, and with some difficulty lights it, for the wind is strong as well as keen, and bends the reed ere it reaches him. After he has lighted his pipe, he will tie up his birds in separate lots and replace them in the bag, then he will go up the road to his cottage ready for his dinner.

The gamekeeper’s life is full of pleasant variety. He has all the pleasures of the poacher and none of the risks, though, of course, if an honest man, he is unable to earn the money a successful poacher does. His social position, too, is not unpleasant, though he is looked upon with a certain amount of distrust by the peasantry; but still, if he is hated by them, it is generally his own fault. He can lead as wild a life as he chooses in the midst of a thickly populated country like England, and most of his time he can spend in the fields and woods–a mighty privilege. He generally knows all the tricks and ways of the poacher, and at times puts them into practice against his brother-keepers. In spring-time he is a great nester, for he is ever searching carefully for pheasants’ and partridges’ eggs. In the shooting season he has much sport, and fills his pockets with presents from the numerous shooting-parties. In addition his regular pay is good. At particular seasons he has to be more watchful than usual, and may have to roam the coverts during the nights protecting the young birds. At times, too, he has to fight, and more rarely to take to flight, for his life; but this is not often the case. Poachers, as a rule, have no animus against the keepers, a fact that Going’s evidence corroborates. In Norfolk the keeper’s work is more varied than in many counties, as we shall see below.” pp. 83-4