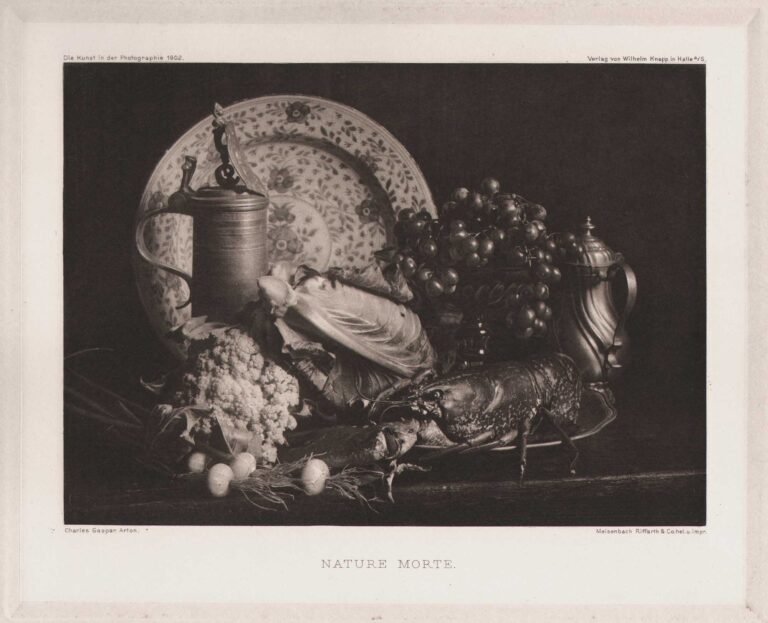

Barmherzigkeit | Compassion

A woman who appears to be a maidservant or perhaps nurse rests in an armchair while looking out towards a window. A burning candle can be seen on a table at far left-the entire composition and title: “Compassion” suggesting an ongoing human vigil.

Max Allihn: 1841-1910

Heinrich Max Allihn– pseudonym: Fritz Anders– was a German writer, Protestant pastor and teacher as well as amateur photographer.

His diverse literary work includes aesthetic and technical writings on artistic photography (pictorialism) , on art, music and pedagogy, as well as humorous regional novels and partly critical social studies of bourgeois life around 1900. With his aesthetic and theoretical reflections as well as the technical and practical manuals on photography, Allihn contributed many important considerations to the Pictorialism movement.

Art photography

From 1889 to 1902, Allihn wrote a large number of texts on art photography and published his own photographs. He dated the beginning of “so-called artistic photography” to 1898. Some of his essays were important impulses for the legitimization of photography as art. In addition, he defined theoretical and aesthetic categories of the artistic-photographic image. Allihn published many of his articles in the monthly magazine Der Amateur-Photograph and in the Photographische Rundschau . His photograph Kinderbild was also printed in Der Amateur-Photograph in 1891. In the commentary to this art supplement, Allihn is described as a “valued collaborator”, which suggests his active and respected collaboration. In 1895 he wrote a handbook on the basics of amateur photography . In 1899 he published Die Photographie – a theoretical and technical handbook that attempted to present photography “without any preconceptions” and thus “appealed to everyone”. However , according to a review in the Photographische Rundschau, the book was “not free of errors and mistakes”. A year later he wrote the article Neue Wege , in which he sharply criticized the institutionalization and aesthetics of art photography.

Photography as Art and the Amateur Sector

Allihn has proposed a clear separation between professional photographers and amateurs, calling the former “technicians” and the latter “artists”. A technician is at work when “the work is carried out according to traditional rules, no matter how skillful”. Thus, all professional photographers, “even those who achieve outstanding results”, are pure technicians, since they create their pictures according to well-considered criteria and compositional rules. In order to create an artistically valuable picture, however, the photographer must allow for the subjective and lively sensation of beauty, which “designs things in a creative way”. In his opinion, only the amateur photographer can do this.

According to Allihn’s argument, the amateur photographer fulfils two basic requirements that are a prerequisite for the creation of artistic photography: firstly, he needs enough time to devote himself to the subject and to train his eye. Secondly, there must be no need to earn money from photography . Allihn emphasises several times that artistic photography is not about reputation and money, but exclusively about amateur artistic creation and idealism. A third criterion for the creation of artistic images is, for Allihn, the combination of talent and study: a “natural gift” of artistic vision and artistic perception, as well as an “eye trained by seeing a lot”.

Correspondence Association of Friends of Photography

In order to train photographic vision and produce good images, Allihn wrote as early as 1889 about the need to study pictorialist photographs in depth: “The main thing is: see! See a lot and see well!” The importance of studying important works of art was also always emphasized by Alfred Lichtwark , the most important promoter of the pictorialist movement in Hamburg. But the amateur movement included many widely dispersed people from different countries who, due to full-time work commitments or remote places of residence, rarely had the opportunity to visit photographic exhibitions. Allihn therefore looked for other means to enable the exchange of images and to improve communication among amateur photographers. In 1889 he presented his draft, and in 1890 the concept for the establishment of a correspondence association of friends of photography . Such an association would be “able to offer a replacement for photographic exhibitions,” as reported in the Amateur Photographer .

Photography and Fine Arts

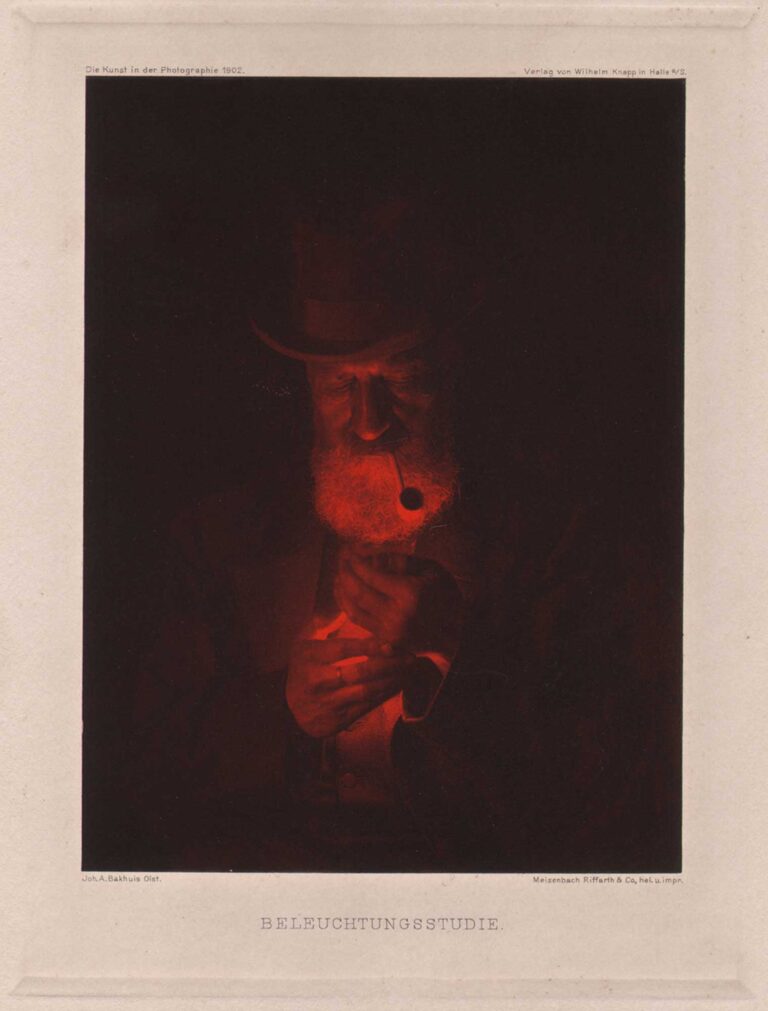

Allihn’s early writing about art and his interest in it also influenced his texts on artistic photography. In his view, photography should always be based on the aesthetics of painting. He always saw the compositional principles of painting and the painter’s view of the world as a model for photography. In his texts, he often compares photographic vision with the vision of a painter, with the latter always being presented as an example: “Anyone who has no eyes, who has no idea of artistic conception, should keep their hands off it [photography].” His photographic texts often contain comparisons with painters. When it comes to the question of the use of light for the aesthetic and compositional design of the image, Allihn refers to Rembrandt and Titian . Alfred Lichtwark also always emphasizes the orientation towards works of art, especially those of Rembrandt. These are the most suitable and most related training of the eye, especially for landscape photography.

Aesthetics and Theory of Artistic Photography

Photographic-technical image vs. subjective eye image

Allihn distinguished between two different types of images: the objectively constructed, “untrue” image captured with a technical device; and the subjective image seen by the human eye as a specific section , which is created in a mental combination of the brain. To differentiate between the two, Allihn suggested using the term image only for subjective images: “If [the photographer] succeeded in creating an image that corresponds to the image seen by the eye , one says: yes, that is an image ; if he did not succeed, one says: that is a photograph .” The camera fixes light stimuli on a sensitive plate using a technical, photochemical process . This creates an artificially “untrue”, light-sensitive image that the human eye could not perceive without the interposition of this device. Allihn cites the perspective exaggerations and snapshots that were often viewed as positive with the invention of photography as examples of a non-human, unnatural way of seeing. For this reason, says Allihn, such photographs often appear artificial and unnatural to people.

Allihn therefore saw the task of art photography as translating the purely technical product of the photographic apparatus into the subjective, natural, which corresponds to human vision. Photographs are therefore only images with art status if they recreate human vision as best as possible. These subjective images are the “object of artistic representation”. In this regard, Allihn also criticized Heinrich Kühn’s photo-aesthetic principle in 1896. Allihn classified his early rubber print Twilight (1896) as an image that cannot be perceived by the human eye: “On the right and left a few dark masses, in the middle a light strip that could represent a path or a stream […]. The image is a mistake. […]. No one has ever seen the world the way Kühn portrays it, even if he squints his eyes. I hope Mr. Kühn will soon return from his misguided path […].”

The Photographer as Artist

The photographer and his artistic achievement are of great importance and importance in the context of artistic photography. According to Allihn’s aesthetic maxim of artistic photography, the photographer should process the technical and objective image in such a way that it corresponds as closely as possible to the subjective sensory impression of human vision. To achieve this, he must “use all kinds of aids and lighting techniques”. The photographer’s subjective, targeted and artistic influence on the image using all possible means is therefore decisive for the quality of an artistic photograph. The photographic process is thus declared to be a creative act and photography is legitimized as art.

Continues- Wikipedia (2024)