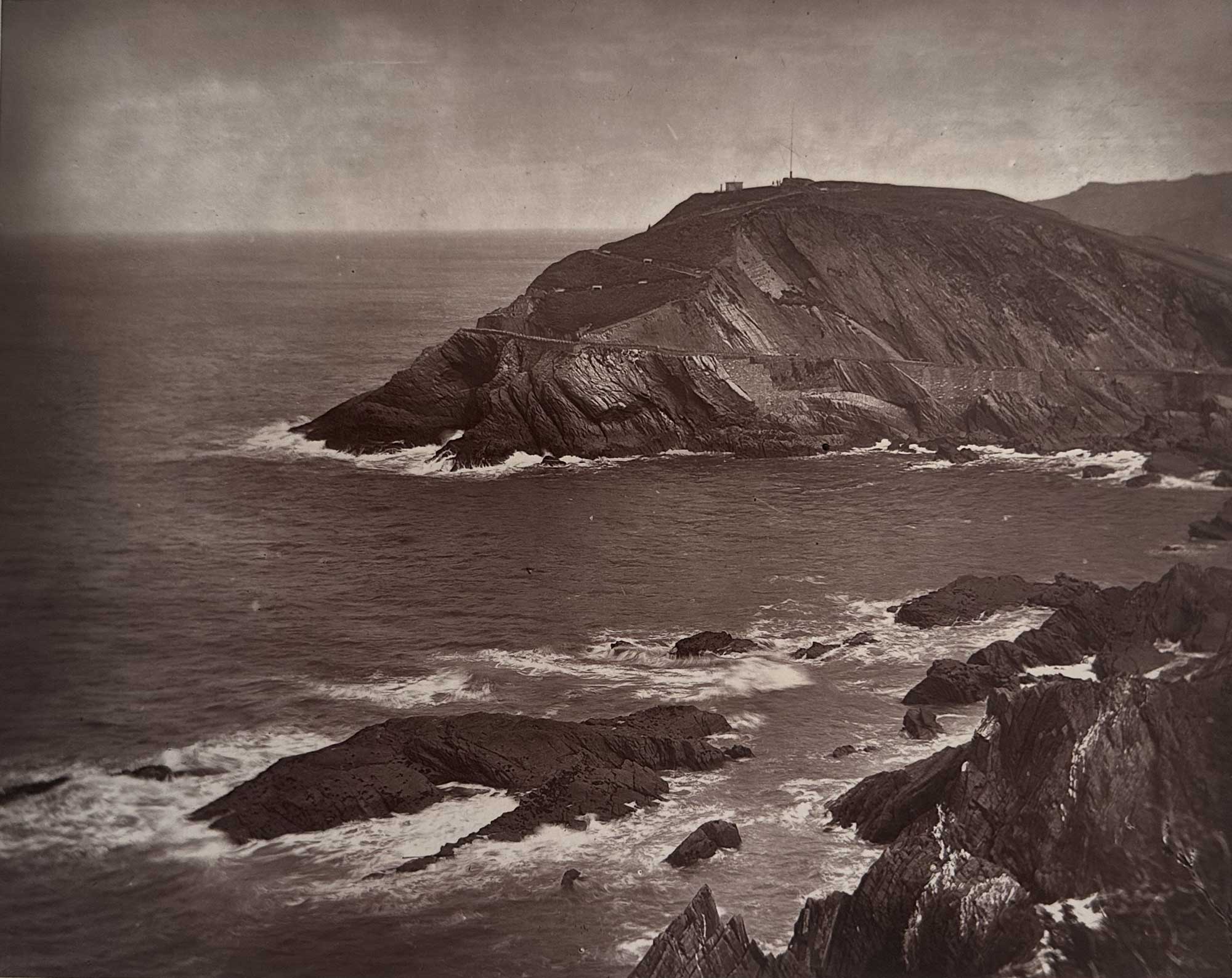

By the Sea, Ilfracombe

Descriptive letterpress printed opposite this photograph:

BY THE SEA, ILFRACOMBE.

“Ah! what pleasant visions haunt me,

As I gaze upon the sea.”⎯LONGFELLOW.

IT may be fearlessly asserted that no other nation regards the sea with the same deep joy as our own race. Of all the external influences which have had their share in moulding the English character, that of “the melancholy ocean” has probably been the greatest.

The sea-board of most other countries is as nothing compared to the superficial area of each kingdom, whereas it is very great in a small island which is only, as Leigh Hunt expresses it, “a moist green field set in the Northern Sea.” Apart from the numerous towns and fishing-villages that everywhere fringe the border of a country compassed by the sea; from its comparatively small size, no inland town can be very far removed from the coast. Starting from any point you will in a direct line, you cannot go very far before coming to the ocean. As a distinguished American once remarked on returning to his own vast continent, “Ours was a very nice little island, but he always felt afraid of tumbling over into the sea.” And this proximity to the ocean has left its mark upon the national character. Consider how large a proportion of the population live even in sight of the wild waste of waters! and in the more remote and wilder rock-bound parts of the coast how many eyes have grown grey and mournful in for ever looking out on the sadness of the sea! How many ears have from childhood been familiar with little else than the monotonous sound of the long roller breaking on the shore, the moaning of the homeless wind, and the wild grandeur of the winter storms so common all around our coasts? And what sea-kings has it not produced ?⎯our Drakes and Hawkins and Frobishers and Raleighs, and numberless others. What wonder that we all love to seize every opportunity of hurrying away where “flash the white caps of the sea, or where we can hear the sea-birds cry; or, lying prone in some sheltered cove, listen to⎯

” the ripple washing in the reeds,

And the wild water lapping on the crags.”

“It is the gipsy blood, urged a restless wanderer in defence of his ceaseless travel in many lands, and perhaps the old Norse element has a share in the sea-roving tendency of an essentially maritime people.

In the presence of the sea we lose something of the littleness engendered by the feverish strife for wealth or fame, that beguiles our senses and robs us of our better nature. The pause, however brief, in the low, sordid influences of city life is wholesome, and brings man more into communion with nature. “The world is too much with us,” “getting and spending;” life’s brief day is too often wasted upon ignoble cares, or withered by all-engrossing, selfish ambition.