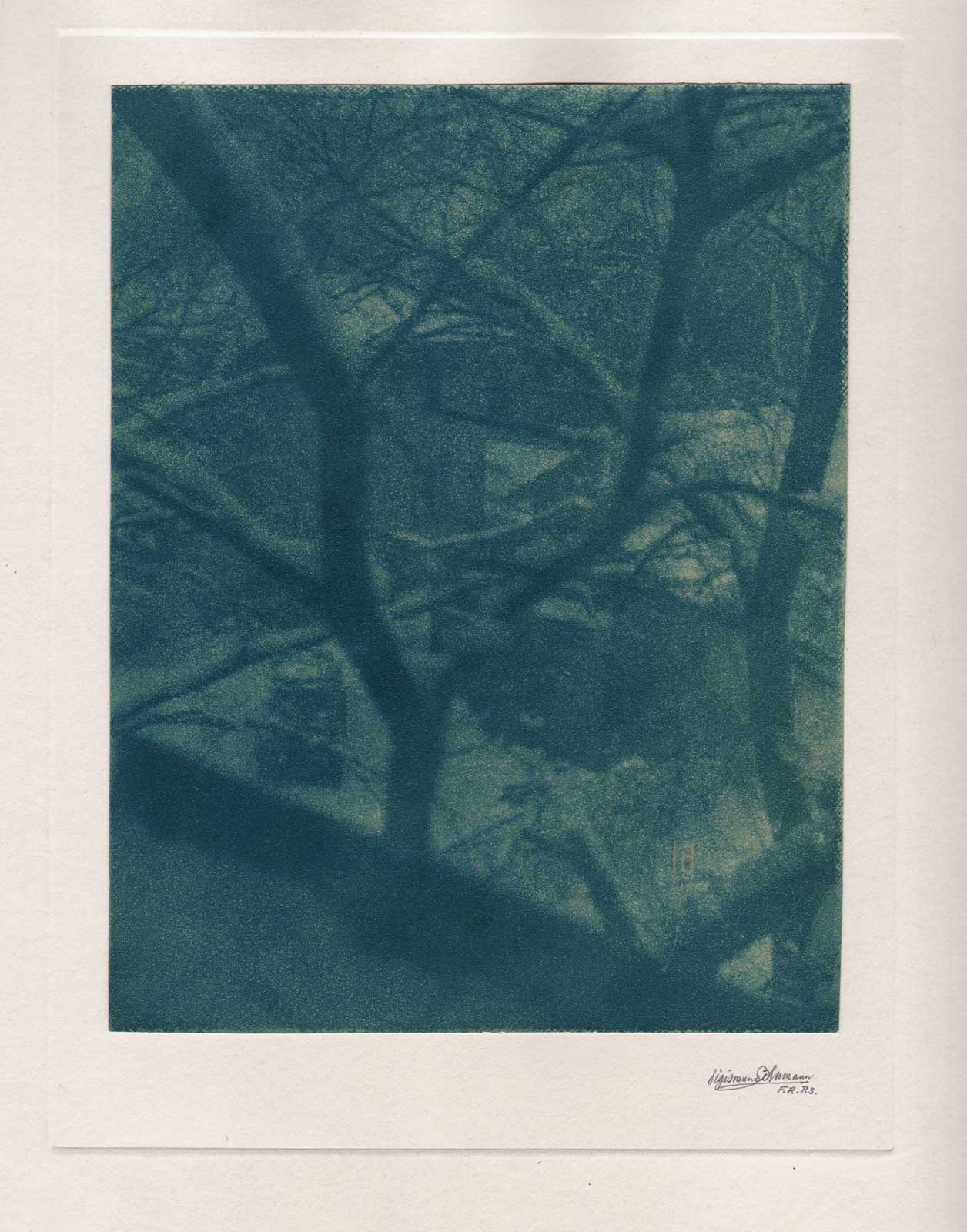

Christmas Night from an Attic Window

Photographed from above through tree limbs supporting several inches of snow, this rare wintertime view by California pictorialist photographer Sigismund Blumann (1872–1956) shows a home courtyard with parked automobile seen through limbs at lower left. Most likely dating to the late 1920’s, this example was printed 1932 or later due to Blumann’s inclusion of his F.R.P.S. affiliation (the year he earned this distinction) within the lower right corner of the primary matt’s impressed window.

Printed in blue | aquamarine tones, this example was done in a process (though uncredited on mount label) Blumann called “Lithobrome”, his own reworking of the better known bromoil transfer process. For this reason, PhotoSeed is assigning this print within the Bromoil print category. Two articles describing the process were published in Camera Craft and follow.

In his Camera Craft column The Amateur And His Troubles, Sigismund Blumann describes the Lithobrome process in the September, 1930 issue:

Lithobrome

The bromoil worker is per se a brave soul who is ready to essay new ventures, and he is apt to be patient as well. Here is a simple after-treatment of the print or transfer which may appeal to him. My own prints attracted some attention and led to several inquiries when shown at the Los Angeles Salon last season.

Take any old, spoiled, but unexposed bromide or chloro-bromide paper you may have and cut it exactly to the size or a hairsbreadth smaller than the size of your bromoil print. Harden it in formaldehyde and dry. This is your tint block matrix.

When the bromoil print is dry, ink up the above matrix with any transparent photo oil color, using a printers roller or so called brayer. Lay the inked paper in careful register on the bromoil and run through the transfer press just as in making a transfer. Then, should you desire to highlight the image wipe off the resultant tint with a clean rag held tightly over the finger. Work gently lest the bromoil be marred.

The color I prefer for so tinting is a neutral brown made by thinning Sepia with turpentine, litho varnish, and very little Japan dryer. Umber is also good.

Do not over ink or the job will spread and be messy. Be sure to roll out the color evenly on a glass slab and take plenty of time. It may be well sometimes to let most of the turps evaporate from the inked matrix before transferring it to the print. A little practice and a few failures will be the best form of instruction.

As no water moisture is involved there is no chance of sticking or uneven contraction. The thing is effective, artistic, and as legitimate as the bromoil process itself or what method of enhancing a print by mounting the maker may choose. (p. 457)

Lithobrome Process, Continued

Sigismund Blumann further commented on Lithobrome for his continuing column of advice titled “Pictorial Devices” in the February, 1932 edition of Camera Craft. The article gives a clue the process wasn’t necessarily restricted to so-called straight bromoil prints as outlined in the above 1930 article but could also apply to creating a finished “Lithobrome” from a finished process print with gelatin (silver) matrix:

It has been said that otherwise offcolor tones which might be prohibitive in professional photography are acceptable in pictorial work. To achieve these advanced workers have been known to add unheard of ingredients to their developers, to resort to astounding after treatments, and to end all by rubbing paints or varnishes on their prints as a finish. I have long made what I call Lithobromes by enlarging through a screen which gives a stipple very like the stone and rubbing well into the gelatine of the dry print a mixture of Sepia and Raw Umber Oil paints. This must be done with discretion. The photographic quality must remain and the paint must give a coating not too apparent. In a word it should enhance, not govern the print. When the picture has been browntoned and is on a buff stock I occasionally find it advantageous to wipe out highlights. My “Sapristi, the Anchor Ees Steeck” shows an Italian Fisherman tugging mightily at the anchor rope. He is humped up in the effort and his light colored shirt shows an effective highlight at the shoulders. This is wiped out as mentioned and the print has been sent to several Salons and has been turned down by none. The judges seem to have overlooked a device or railed to detect it. Verily, art lies in dissembling art. (p. 68)