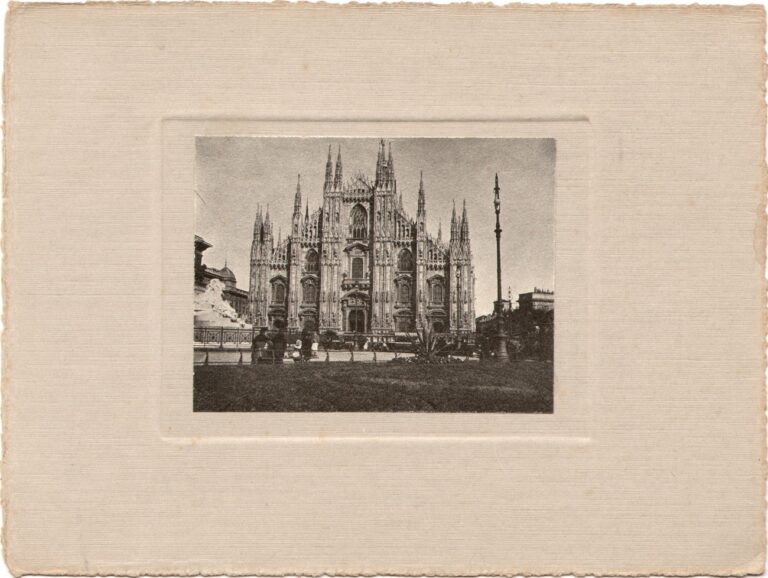

Edith Wynne Matthison in The Terrible Meek

The Terrible Meek by playwright Charles Rann Kennedy, 1871-1950, was “A One-Act Stage Play for Three Voices: To Be Played in Darkness” first performed on Broadway in 1912. This photograph of the actress Edith Wynne Matthison (1875-1955) in the role of the “Peasant Woman”, a stand in for the symbolic role of the Virgin Mary, was used as the frontispiece to the volume published by Harper & Brothers the same year.

The play was poorly received in its day, with The Theatre magazine publishing the following review in the May, 1912 issue after it had already closed on Broadway on April 1 after 39 performances.

One had to be good-natured to forgive “The Flower of the Palace of Han,” but “The Terrible Meek” was an imposition. It is about as stupid an offering as has been presented of late years by a professional company. When Charles Rann Kennedy wrote “The Servant in the House,” he evidenced his belief that the success of the play was due to its religious teachings. The success of that play was due to its sensationalism, and it was more sensational than anything ever presented in the theatres of the East Side. Mr. Kennedy must have realized this element in his success, for while he makes “The Terrible Meek” deal with religious platitudes, he makes his scene revolting to every clean mind, and his finish a shock to an audience, who can scarcely comprehend the audacity of any man in handling a subject so sacred. He takes an unfair advantage of his audience by withholding information to create suspense. It is a device that has been abused more than any other upon the stage. In this case, it is carried to such an extreme that the audience cares little about what the withheld information is.

Out of the darkness comes the voice of a woman sobbing as if her heart will break; a man’s voice tries to comfort her, but she repulses him, telling him that he has the “smell of death upon him.” It may be a bedroom, or a police court, almost anything but what it is. Our imagination can run as to the identity of the characters. Facts are not established.

When, after a long period, a little patch of moonlight shows us a robed figure seated near a post, and a woman prostrated at the foot of that post, it is with repugnance that we gather that we are at the foot of a gallows upon which a man is hung; we can almost see him dangling in the breeze, while his mother below treats us to such beautiful descriptions of dripping blood, and of the mangled breast, that we feel, more than anything else, like going home to forget it. We presently discover that the robed figure is a captain; this information from a sentry who comes with a lantern, that for some mysterious reason fails to give any light to speak of. A little color is given by a Cockney accent upon the sentry’s part. Who are these soldiers? What country do they represent? In what conflict are they engaged?

Those facts are not established to the end of the piece. The Captain is conscience-stricken, because it was his order that caused this woman’s son to be hung. The only thing that prevents him from converting the sentry to his way of thinking, is that killing is the sentry’s business; and the sentry, if under orders, would “shoot God Almighty ‘imself if ‘e come out of ‘eaven.”

It would be to no purpose to describe any more of this rubbish; suffice it to say that the Captain begs the mother’s forgiveness, receives it, and goes to his death for refusing to obey his General, who has sent him orders, by the sentry, to do some more killing. A transformation now takes place, and for the first time we definitely see who these people are; while the supposed gallows, now seen in entirety, is Christ upon the cross. other crosses hold the traditional thieves. The Captain is a Roman soldier; the mother a poor peasant woman, plainly the Virgin Mary, and the sentry a soldier of a nondescript type. We have come to know Charles Rann Kennedy as a man of sincere and deeply religious feeling; but this work, which can be judged only for itself, verges close on the blasphemous. As it stands, it is distinctly stupid, and with about every fault that a play could have, filled with tiresome repetition, preachments and unestablished facts. idea could be presented in dramatic form; but given so that its entire significance is clear, it would be swept from the stage by popular indignation. It is one of a large class of plays called impossible. For the information of the curious, it may be said that the title comes from the relentless power of those who are dead and gone, to move conscience and to sway destiny.

Miss Edith Wynne Matthison did all she could as the poor peasant mother. Mr. Sidney Valentine was entirely sincere as the Captain, while Mr. Reginald Barlow carried off the honors of this piece as he did the other one, in his characterization of the sentry. “The Terrible Meek” really applies to the audience. pp. 139-40

Perhaps sensing the end of its Broadway run was near, a letter written by playwright Charles Rann Kennedy was published by the New York Times on March 26, 1912:

Among the misrepresentations circulated concerning my play, “The Terrible Meek,” there is one I should like, by your courtesy, to correct. It is to the effect that “The Terrible Meek” is a representation of the actual events of the Crucifixion, with the implication that this done for merely sensational purposes.

My real purpose is, perhaps, rather more startling; it is to awaken people to the realities of the religion they profess, especially bringing them to bear upon actual problems of the day. It has always appeared to me that the Passion and Resurrection of our Blessed Lord illuminated these problems. And, judging from their letters to me, the clergy who are attending the special clerical matinee of the play next Thursday agree with me. CHARLES RANN KENNEDY. New York, March 23, 1912.

Alice Boughton, (1867-1943) a well respected New York portrait photographer who studied in Paris with Gertrude Käsebier and also worked as an assistant in Käsebier’s New York studio before striking out on her own, was appointed a Fellow of the Photo-Secession by Alfred Stieglitz and had her work published in his journal Camera Work.