Eel Picking in Suffolk Waters

From Chapter XVII: Eel Picking

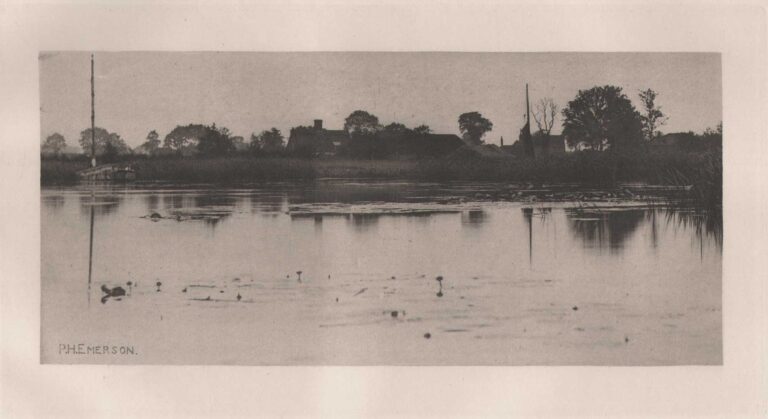

“AFTER the fishing season is over, at the end of December, the Southwold fishermen, when not shrimping, fill up their time by eel-picking, net-making and mending, and sundry other jobs. It is often impossible for them to go out on the cold North Sea at such times, for nothing is to be got there save rough weather. Another reason why the eel-picker defers his sport till winter is the difficulty, nay, almost impossibility, of getting any eels in summer, for they “fly” during the summer, that is, they leave the mud, and are vagrants in the dikes, swimming hither and thither. The pick, as shown in the plate, is a picturesque tool, not unworthy of the sons of Neptune. It is generally made by the local blacksmith for the modest sum of five shillings, the fir staff, however, costing extra. This particular pick is locally called a “gall-pick.” It will be seen that it consists of two barbed metal prongs placed between two other rough-hewn prongs. There are, besides this pick, various kinds in use in different parts of England. The experienced eel-picker generally chooses a quiet day, because there will be no ripples on the water, and a morning light, so that he may distinguish the ” blow holes.”

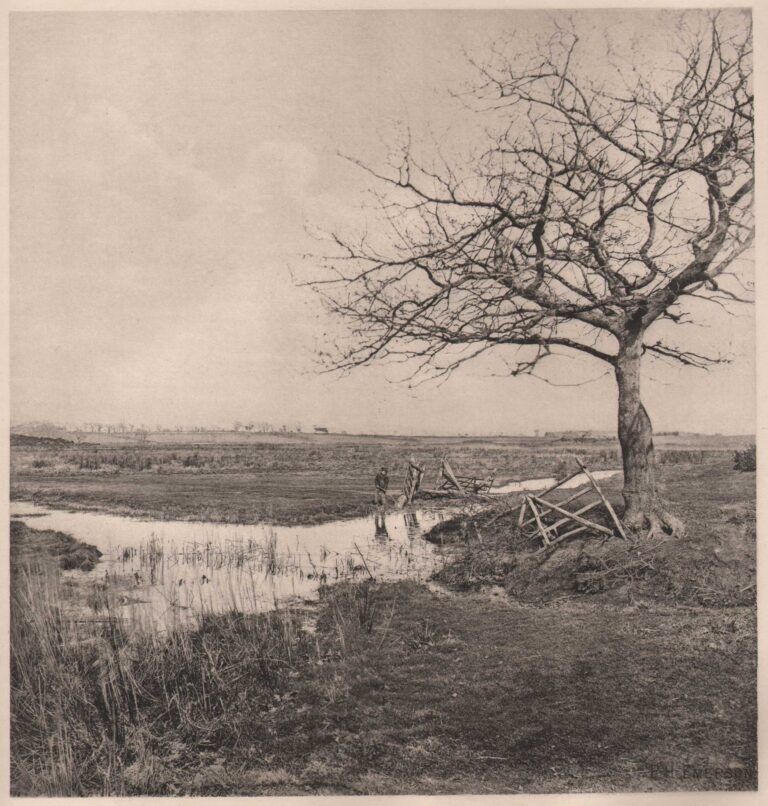

Shouldering his eel-pick, he strides across the common to the dikes, and, walking slowly along the edge of one of them, he looks carefully under the banks for “blows.” A “blow” is a round hole with a circlet of blue, much the colour of ink, round it, its size depending on the size of the eel. Each eel has two blows, separated from each other by the length of the eel they harbour. Here it seems the eel lies buried during the cold weather, the blows evidently being his breathing-holes. If the eel-picker can see the two blows, he strikes his pick with a quick movement as nearly as possible between the two holes, whereas, if he can only see one hole, he must take his chance, and, if he strikes wrongly, the eel will depart by the distal end. All these blows are under water. Sometimes the pick will bring up the eel coiling all around its teeth like a “wiper,” at others, it will come up hanging stiffly and oscillating slightly, while at others it will be quite dead and flaccid, due, we should think, to the prongs having penetrated the brain. When the eel comes up, the man rubs his pick up and down on the grass to rub off his slippery prey, which often instinctively glides towards the dike, but is stopped by a death-blow from a stick. As in other sports, the eel-catcher’s luck is subject to great variations. He may get none at all, or he may get two stones of eels in a day, but an average catch for a good day’s work is one stone of eels. The men look to get two or three pounds in a “short morning.” When eels are scarce, the catchers get sixpence a pound for them from the “marchant,” but fourpence is the average price obtained, while the public have to pay a shilling a pound. The silver-bellied cel is the only species caught in the Southwold dikes, whither they go in summer to breed from the river and sea, entering the dikes by means of the sluice-gates.” p. 109