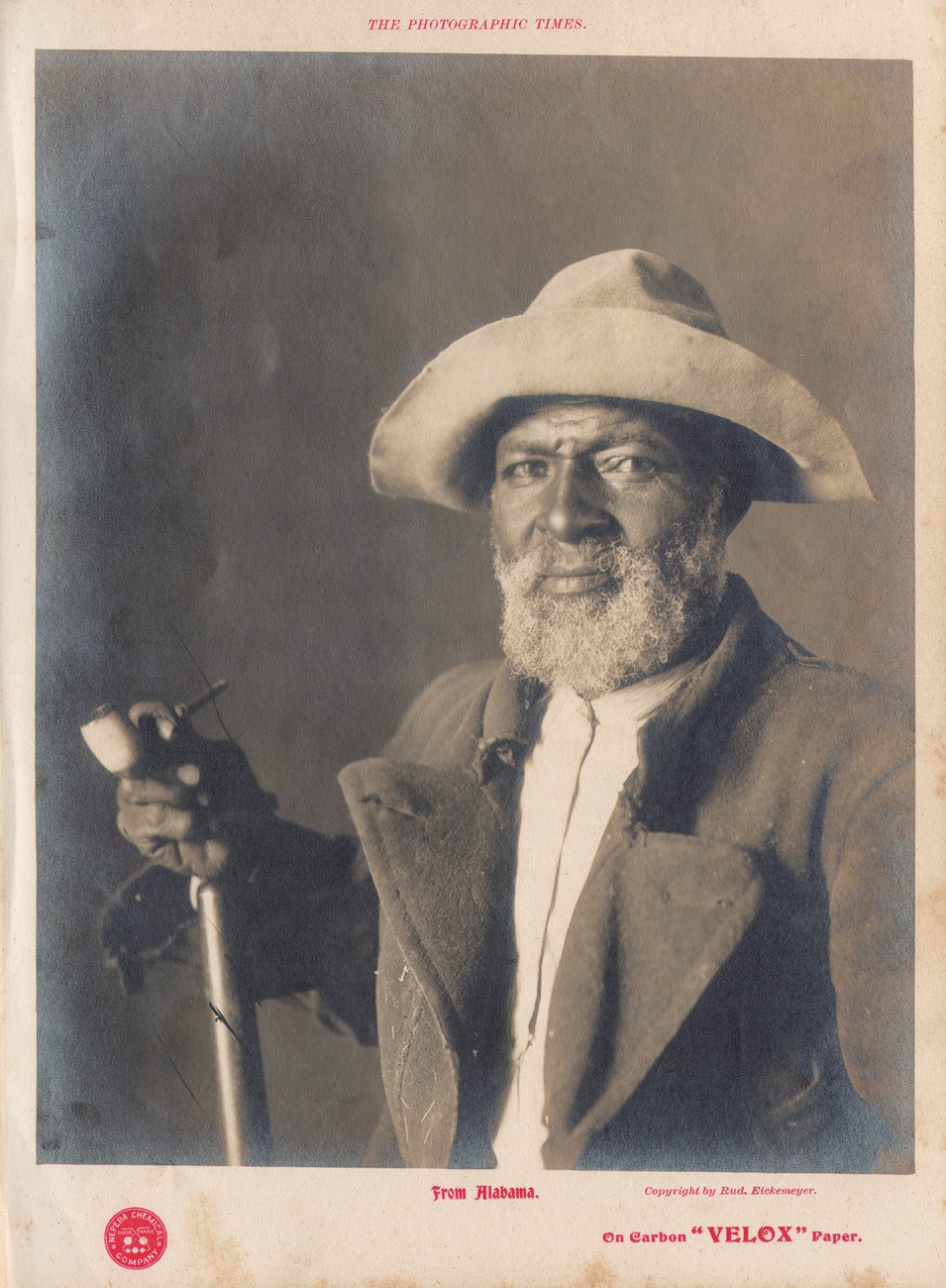

From Alabama

From Alabama, a portrait of a freed African-American slave holding a pipe while resting his hand on the back of a chair, was taken by American photographer Rudolf Eickemeyer, Jr. in 1894, somewhere around Mt. Meigs, Alabama. A variant portrait, commonly known as Uncle Essick, shows the same subject in three-quarters view from behind holding his pipe from the side. Uncle Essick was later published as a full-page halftone plate in the volume Down South, a series of photographs taken by Eickemeyer in the region and written by Joel Chandler Harris. It was published in 1900 by R.H. Russell of New York. This subject’s proud face belies a cruel chapter of American history-that of forced slavery and ownership of another human being- but nonetheless, a remarkable surviving document that succeeds in that it does not overtly gloss over this gentleman’s reality of impoverishment, notably seen in the clothes he wears.

When it was published as a supplement included in the May issue of the Photographic Times, From Alabama was meant as a promotional example of Carbon Velox photographic paper, with the brand name overprinted in red ink on the bottom margin of the photograph itself. The following editorial comment appears opposite the photograph, alluding to the qualities inherent in gelatin silver Velox with respect to exposure speed, chemical processing ease, and volume potential:

Most of our readers are undoubtedly acquainted with Velox paper. A paper that can be printed at night as well as in the daytime, and which does not require a dark room like the ordinary bromide paper, was bound to become quickly popular. During the last three years the Nepera Chemical Company has been steadily improving the product and simplifying its manipulation to such an extent, that the whole process has become one of proverbial simplicity.

Our photographic friends abroad have not been slow in availing themselves of the great possibilities of Velox paper, and there is scarcely any country in the world where photographs are made where Velox is not being used.

Our illustration opposite was made from a negative kindly loaned by Mr. Rudolph Eickmeyer, Jr., the thousands of prints for this number were made from this one negative at the rate of 750 to 1000 a day. The printing was done by diffused daylight, each exposure requiring a very few seconds. A small boy does the printing. Each print is run through a tray containing Metol-Quinol developer; the image flashed up suddenly, then development seems to stop, and this gives enough time to dip the print into the acid hypo bath, which stops all chemical action of the developer and fixes the print. All these operations are performed by full gaslight, and are much simpler in practice than they appear in print.

It was thought in the beginning that the Velox process was only practical in such cases when a great many prints have to be made from one and the same negative. After a very little practice, however, it is so easy to judge the strength of the negatives, that if prints are exposed to a steady source of light, for instance, gaslight, there is not the slightest difficulty in printing, developing and fixing twelve good prints from twelve different negatives within fifteen minutes. (1.)

1. Editorial Notes: in: The Photographic Times: New York: May, 1898: p. 225