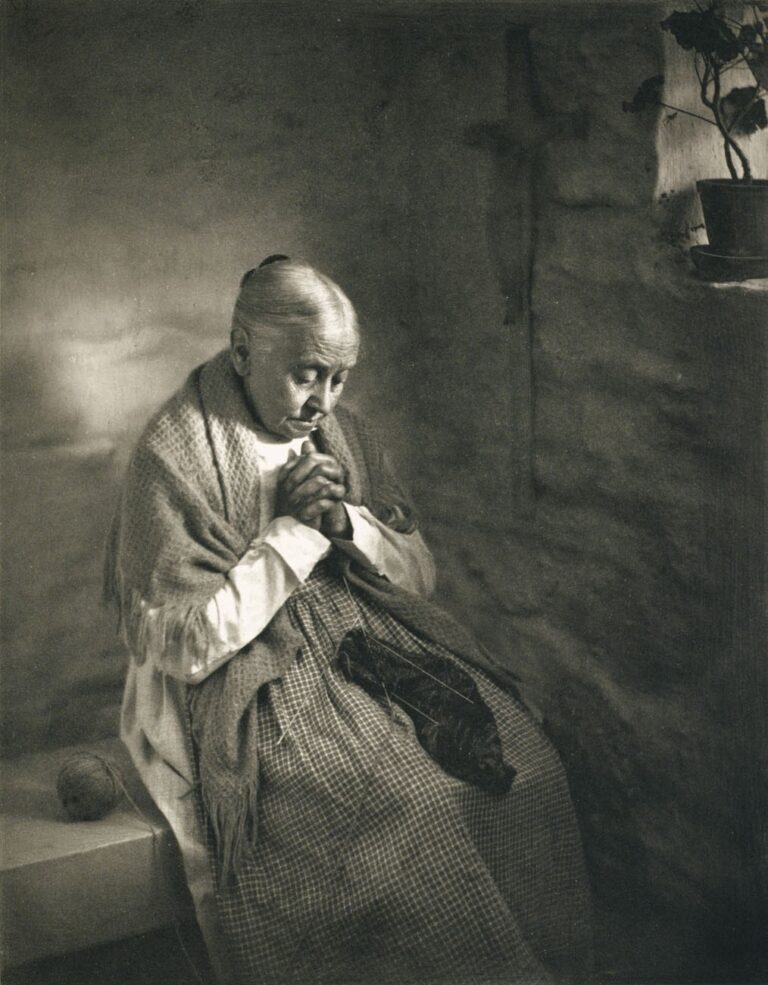

In the Shadow of the Rock

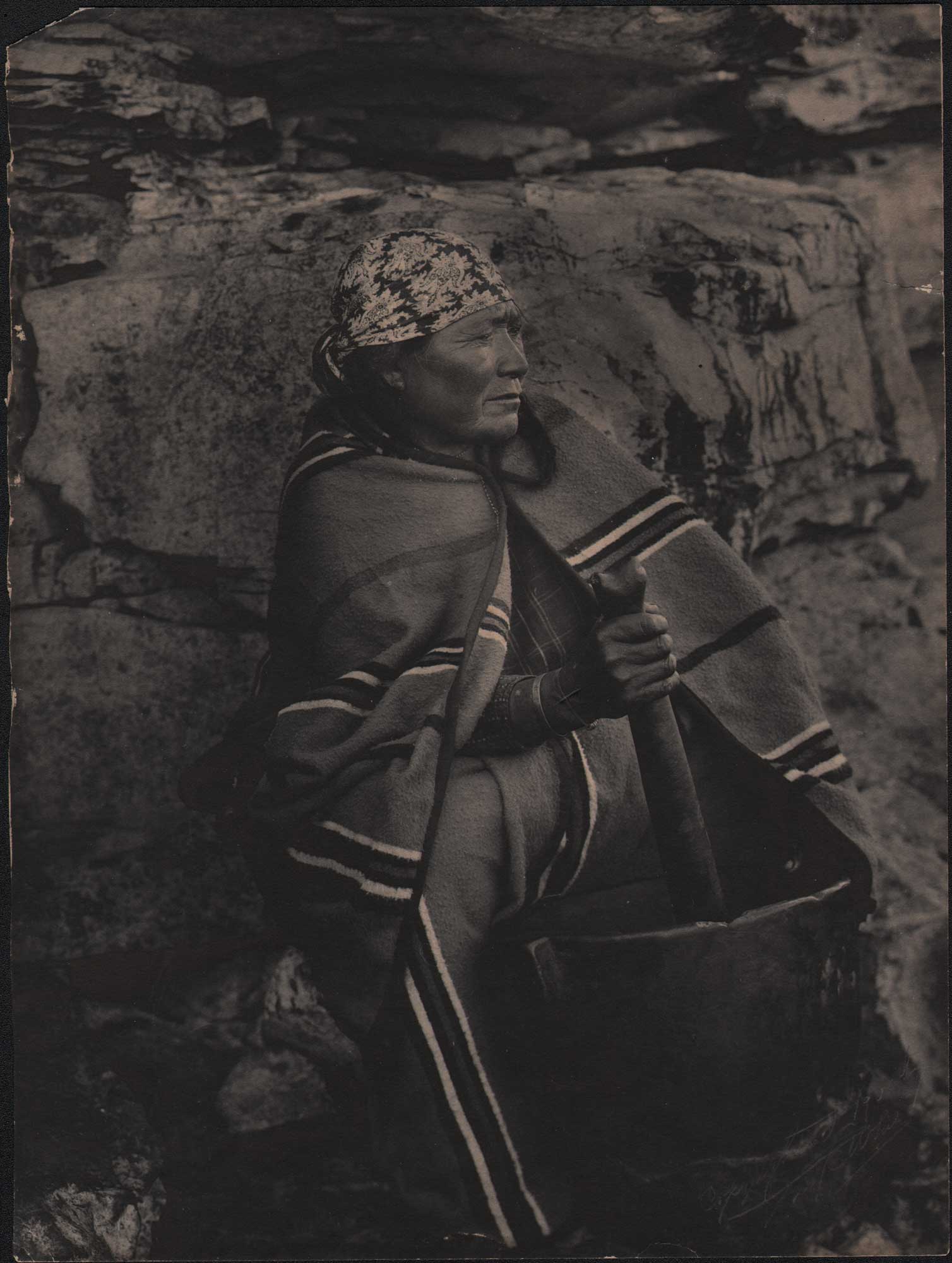

A Wishram woman from Klickitat County, Washington state, uses a traditional wood mortar and pestle to prepare food. This extremely rare signed platinum print photograph is a very early example of the work of Lily Edith White, who joined the Oregon Camera Club in 1898. White is also notable for being one of the very first west coast associate members admitted to the American Photo-Secession founded by Alfred Stieglitz.

The Oregon History Project online portal gives a detailed description of food preparation using mortars by the Wasco and Wishram peoples:

Mortars were used by Wasco and Wishram communities—and by indigenous peoples worldwide—as they prepared their foods, collected during the spring, summer, and fall, for winter storage. Meats, roots, seeds, and nuts were mashed into powder with the aid of a stone pestle, a hand-held, club-shaped implement with a slightly rounded end. Sometimes, in far-flung locations, visited seasonally for the collection of roots, mortars were carved into locally-accessible large stones or downed logs, then left in place, to lighten transportation loads to and fro. At more permanent village sites, such as along the Columbia River, where food was available for most of the year, portable mortars were constructed of hardwood.

Compared to their female counterparts of the Columbia Plateau, who typically contributed roughly half of the community food supply, Wasco and Wishram women gathered and prepared fewer roots, berries, and nuts for their villages. Much of their time was instead spent helping to prepare the enormous volume of salmon that Wasco and Wishram men caught from the Columbia River at various rapids and at Celilo Falls, the most productive salmon fishery in the Pacific Northwest and perhaps all of North America. After drying the salmon, women pounded a portion of it into a fine powder, added some fish oil, and then mixed it with dried berries to produce a salmon pemmican. Pemmican was highly nutritious, easy to pack, and if made properly, could be stored for a year or more. Dried salmon and pemmican were greatly valued in trade throughout the Pacific Northwest. Wasco and Wishram women traded them for already-prepared foods such as dried elk and deer meat, biscuits and loaves of camas, wapato, biscuitroot, and bitterroot, and other non-edible trade goods.

Lily Edith White: 1866-1944

The following biography of White by Carole Glauber appears as part of the Oregon Encyclopedia, an (online) project of the Oregon Historical Society.

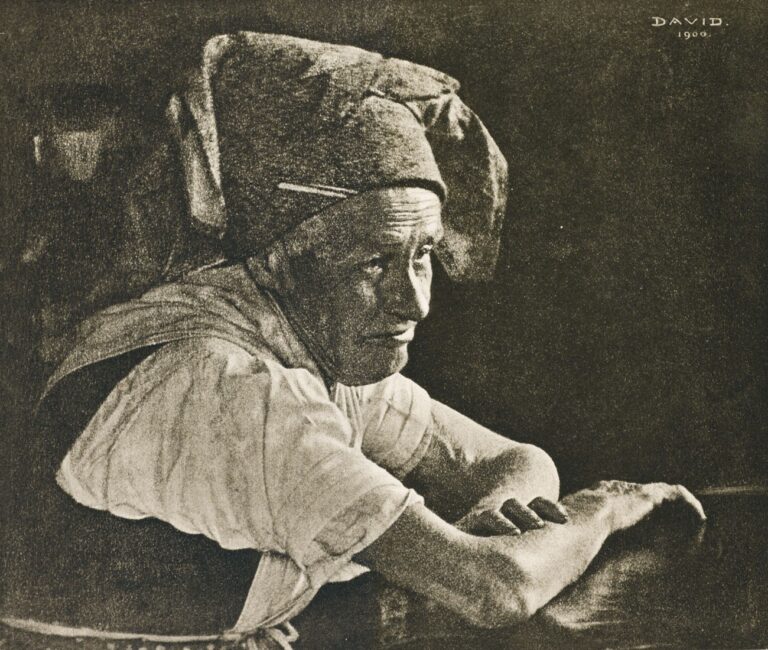

Photographer Lily White once professed: “Alone—controlling the power, directing the course—one might be so filled.” Dubbed the “Captain” by Columbia River boat officers and crews, White is best known for the photographs she made while traveling on her custom-built houseboat with her friend and fellow photographer, Sarah Hall Ladd.

Lily Edith White was born in Oregon City on May 10, 1866. Her mother, Nancy Hoffman White, had crossed the plains from Illinois at age eleven with her parents and twelve brothers and sisters; and her father, Edward Milton White, worked as a riverboat captain. Her grandfather, Samuel Simpson White, served as justice of the peace and probate judge in Portland and was elected a member of the legislature in 1847. He built the Lot Whitcomb, the first steamer on the Willamette River.

White studied art in San Francisco and Chicago, where she learned portrait painting. By 1886, she was working as a clerk for W.B. Ayer in Portland and living in her grandfather’s home. By 1891, the year her father died, she was working as a bookkeeper for photographer W.H. Hunt.

White joined the Oregon Camera Club on March 3, 1898. Founded in 1895 with a membership of eighteen, the Camera Club selected new members by ballot. Honorary and “lady” members enjoyed all the privileges of the club but could not vote or qualify for office. Members’ work was showcased at annual exhibitions that also served to publicize the club.

White’s proficiency in photography was such that in June 1899 the club employed her as assistant secretary. She also assumed the position of club demonstrator to instruct the group. In 1900, when White demonstrated “Negative Taking” at the club, she listed her livelihood as “Artist, Oregon Camera Club.”

The Oregon Camera Club opened its fifth annual exhibit in 1899, with 300 photographs on display. A local newspaper credited White with responsibility for the members’ improvements and the subsequent growth in membership, which had reached 175.

White participated in Oregon Camera Club exhibits in 1900 and 1901 and exhibited her photographs in the San Francisco salons at the Mark Hopkins Institute of Art in 1901 and 1902. She became a nonresident member of The Camera Club of New York in 1902. That year, White’s peers in the Oregon Camera Club presented her with an honorary membership. For unknown reasons, she resigned from the club in 1904.

In 1903, White and Sarah Ladd were among the first associate members admitted into the Photo-Secession, an avant-garde group of photographers organized by Alfred Stieglitz in New York City. This placed them among the most prominent artistic photographers of their era, though White never exhibited her work with them.

At about the same time, the two women began spending time on the Columbia River, living on the Raysark, an 80-foot-long houseboat equipped with running water, an up-to-date darkroom, and a photographic “outfit.” They created an extensive collection of photographs of the river, many of them published in The Pacific Monthly, owned by Ladd’s husband, Charles E. Ladd.

In 1906, the magazine published three articles highlighting White’s work, including “From the Log of the Raysark,” White’s personal experiences as captain of her houseboat. The Columbia River and Puget Sound Navigation Company published a promotional brochure, “Up the Columbia,” with photographs by White and other local photographers.

By 1905, White was no longer making photographs, and in 1909 she was listed in the city directory not as an artist, but as a Christian Science practitioner. She moved to Carmel, California, in 1923, and died there from “apoplexy” on November 14, 1944.

The Wishram are known as the Tlakluit and Echeloot. They traditionally settled in permanent villages along the north banks of the Columbia River. In the 1700s, the estimated Wishram population was 1,500. In 1962 only 10 Wishrams were counted on the Washington census. Their main summer and winter village on the Columbia River, Washington, was Wishram village, referred to as Nixlúidix by its residents. It is considered the largest prehistoric Chinook village site. The site is now part of Columbia Hills State Park. Located near Five Mile Rapids, the village was located at the far eastern reach of Chinookan lands. The village and the name for its people as ″Wishram″ comes from the neighboring Sahaptin-speaking tribes, which called the village Wɨ́šx̣am/Wɨ́šx̣aa – ″Spearfish″, and its people therefore Wɨ́šx̣amma – ″Wishram people″. -Wikipedia (2025) continues