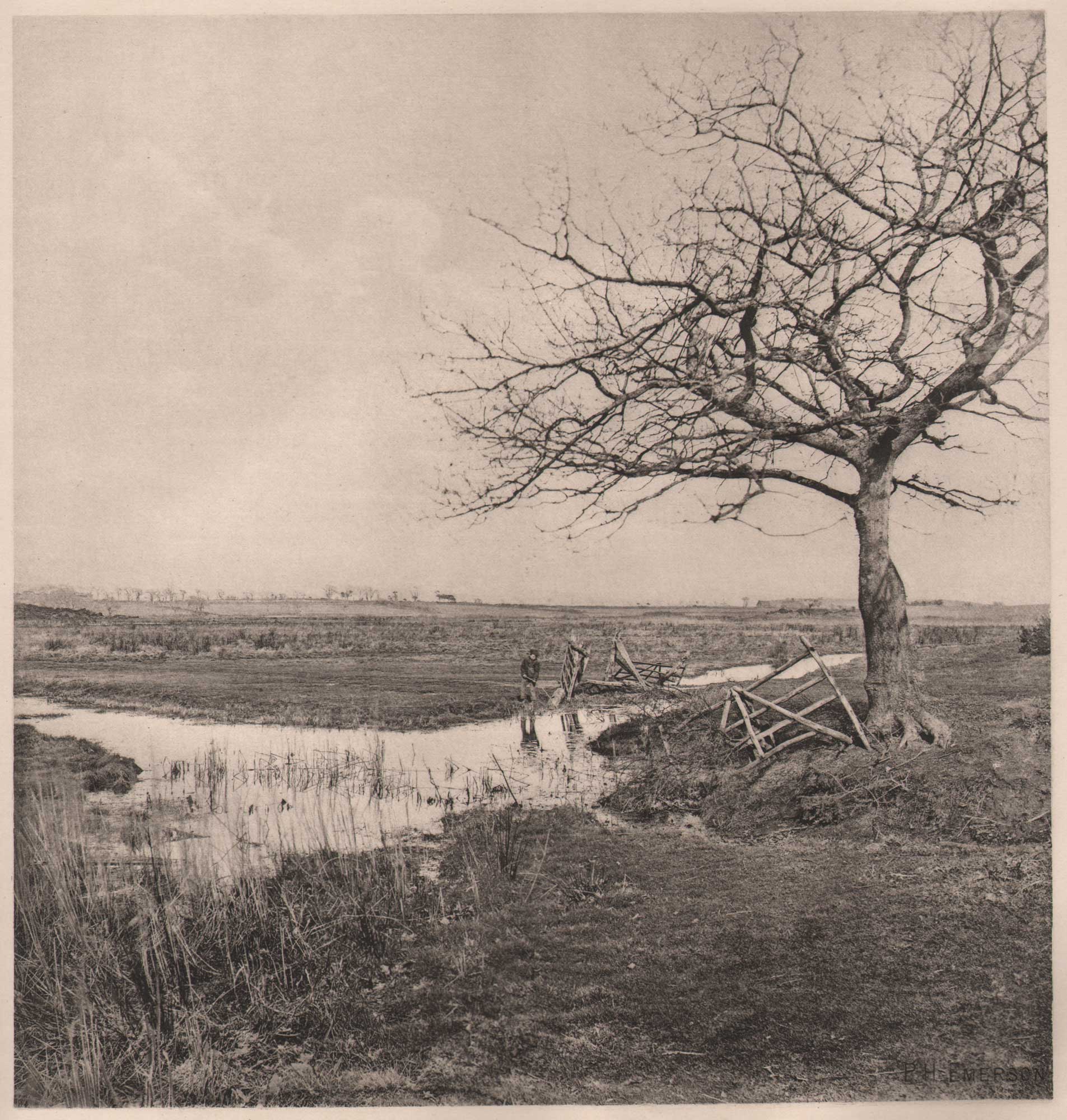

Leafless March {Suffolk}

Bleak Suffolk marshland is the subject of this landscape, interrupted by a lone tree and young boy in the distance caught by the artist’s camera trying to hook a pike. Emerson goes on to describe the seasons of the year as they come to this particular spot of Suffolk earth, a creative and lasting way of speaking of the life taking place here.

“His pictures never look like compositions; indeed, he is as successful with some of his groups as with mere landscapes like “Where winds the Dike,” or like the still more perfect “Leafless March” (the reproduction of a bit of Suffolk marsh, which is Messrs. Walker & Boutall’s sole contribution to the volume).” —The Academy, August 11, 1888, p. 79

“Leafless March, though there are many qualities I like in this plate, its great fault to my mind is, that it is too sharply focussed throughout.” ⎯ P.H. Emerson, Sept., 1889, To The Student

From Chapter VII: Leafless March

“But we have wandered from the view and from our walk, which, in spite of our musings and talkings, soon brought us to the subject of our plate-a bleak spot, inhabited only by a bare and gnarled tree. A hurdle stands to the left, placed there to prevent the straying cattle from wandering over the neighbouring marshes which lie beyond the shallow water. By the tree flows a dike, met in the foreground by two other dikes. No hedgerows divide these Suffolk marshes, but only waterways, now drear enough and destitute of all vegetation save some few straggly broken reed stumps. All is cold and dreary. No cattle graze on the marshes; they have been driven to the warm farmyards, where they feed protected from the cutting North Sea blasts which scour the lowlands. Lapwings are the only congeners of this bleak landscape, save for the little boy, who, with a dead bait rudely fastened to a rough-hewn ash-stick, is hoping to hook a pike that has for long held cruel sway in these peaceful waterways. Beyond the marsh is visible the line of the marsh-road, now deserted, but in summer-time the scene of many an idyl; and farther on is the cultivated upland, with its gently rising fields, its trees and hedgerows, leading up to the farm-buildings on the right hand. Along the sky-line are silhouetted the trees of leafless March, beautiful in tone, subtle in drawing, and strong in character. At this season the aspect of the country tells us that the destroying angel of winter has done its worst; man alone is full of hope, for he knows that in a few weeks the winds will change, and life-giving spring will return with the warm sunshine, balmy showers, and gentle zephyrs. Then the air is full of the cries of snipe and lapwing, of ewes and lambs, who wander in groups over the grass, tended by the careful shepherd-dog. The cows, with their calves, colour the pastures with their whites and blacks and reds. Over the marsh comes the sound of the peasant’s voice, as he guides the light harrow or the heavy drill. In the dike the teal and wild-duck, the coot and water-rail, swim with their fluffy broods, ever keeping near the reedy growths; and the young pike dart away as they see the wayfarer’s shadow. Children, too, now wander over the marshes, gathering the modest primrose and brilliant kingcup. The shepherd-boys make whistles from willow stems, cut for them by the hardy hedger, who is now working on the uplands. In the hedges, first the black-thorn then the white-thorn puts forth its starry blossoms. Later, when the summer comes, the cattle roam the marshes chased by the stinging flies, or standing knee-deep in the rank grass, seek to cool themselves from the scorching sun. The fields grow yellow with corn and the orchards hang heavy with fruit. As autumn draws near, the reed-cutter takes his sickle, and cuts the long reed-stems, carefully piling the crop ready for the carter’s hand.

Then comes a wild whirlwind, and the leaves fly from the trees through the air on their death-flight; then the gales of later autumn sweep across the marshes, scattering before them the heaps of richly stained russet and yellow and purple leaves, and breaking and bruising in their eddying fight the golden reeds fringing the dikes.

The roar of the angry surf murmurs hoarsely across the marshes, the wind howls through the trees, while the gulls fly inland seeking safety, and the marsh-men, with bent figures, hurry along the bleak roadway to the farm. Colder grow the days and greyer, until silently comes the white snow, blinding both man and beast as they return home from the pastures. Noiselessly but persistently it falls, and covers path and field and dike. Then black frost doth freeze the waterways, covering the dikes first with granular ice, then with smooth hard sheet-ice, on which ring the runners of the rustic skaters.” p. 69