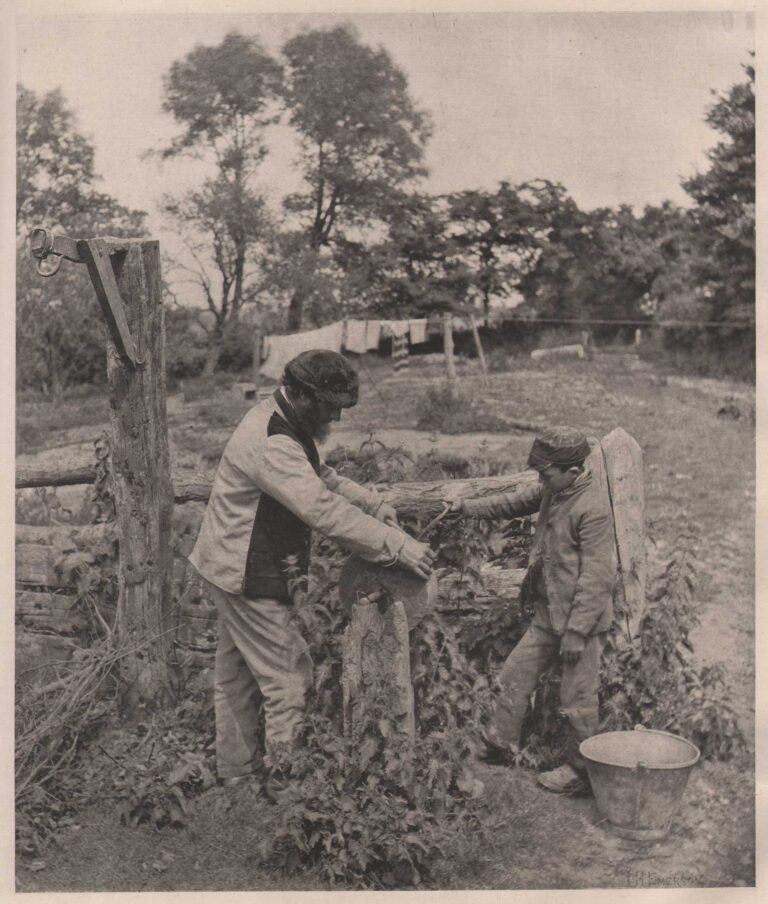

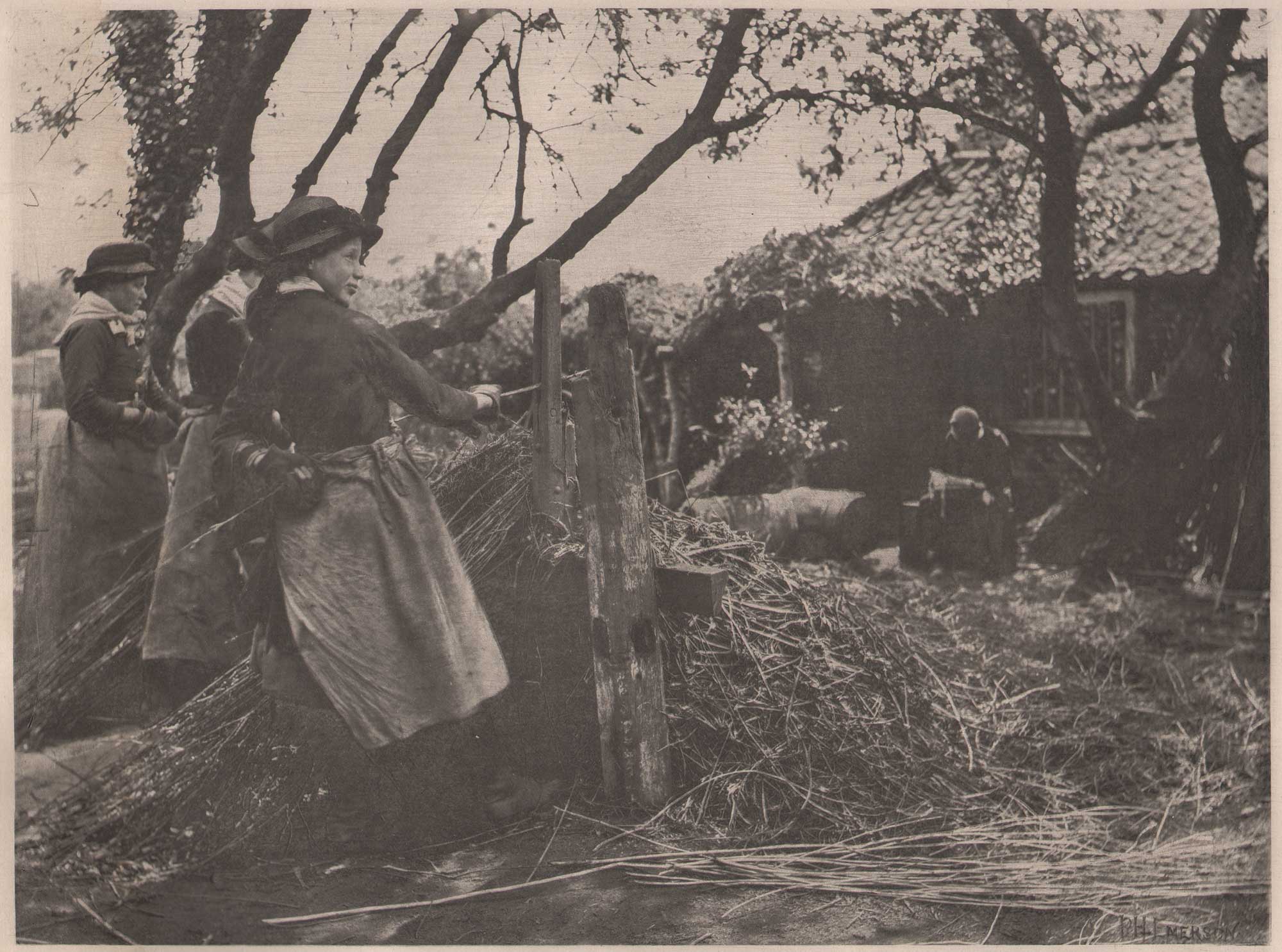

Osier Peeling {Norfolk}

From Chapter XV: Osier Peeling and Basket Making

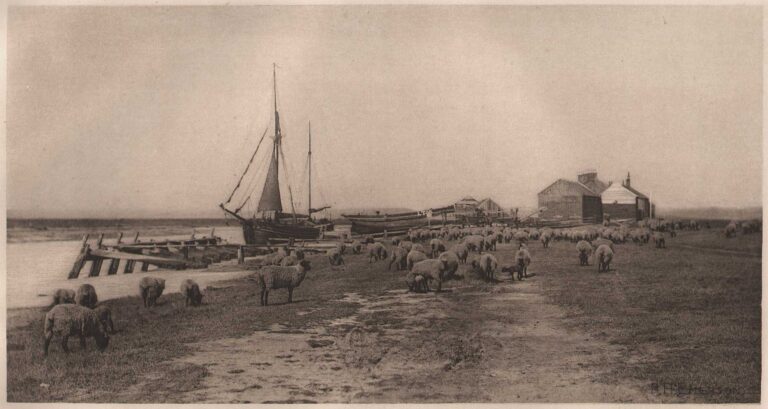

“HERE we have a basket-maker’s yard as seen by us one beautiful day in early spring. Here, at the brakes, we see three women hard at work peeling the pliant osier stems, while the sun glints through the leafless trees and lights up the dark scene. A donkey, all unconscious, is feeding knee-deep in a pile of sweet mucilaginous peelings, and to the right sits a boy trying his ‘prentice hand at basket-making. Through the large windows we can see a more experienced hand busy bending the withered rods and fashioning the rough hamper, which we can picture to our-selves, when finished, travelling full of hares and pheasants, wild-fowl and venison, salmon and grouse, from one end of Great Britain to the other. The intelligent prentice has seen us, and comes up politely, volunteering to show us everything; so we desire to begin at the beginning, and learn the art and science of basket-making as practised in Norfolk at the present day. The osiers, he told us, were usually cut in April, by regular hands employed for the purpose, whose wage was threepence a bunch, each bunch measuring seventy-two inches round, two bundles measuring thirty-six inches each, making one bundle. The implement used for cutting is a hook. The osiers are grown in small patches on the marshes near the broads, and in some districts seem to pay better than in others. But we have heard very conflicting evidence from trustworthy men as to the value of osier-cultivation; so much so, that to the present day we are rather mystified as to the real value of such a crop. One thing, however, seems certain, that of late years the supply exceeds the demand. The basket-maker buys the osiers from the farmer for five or six shillings a bunch, or two-and-sixpence to three shillings a bundle, including cartage. When they arrive at the basket-maker’s, they are put in a dike containing a little water, and here they weather, the object of which is to loosen the peel, which facilitates the peeling. We have seen the dike full of bunches and bundles all sprouting, many with full-grown leaves, looking like osier-plantations growing in very close quarters. They remain in this bath from April to June. If, however, they are intended for rough use, they never go to the dike at all, for they are not peeled, but laid out in the sun to dry and “brown,” and the two kinds are always distinguished as “whites” and “browns.” To return to the whites, which are used for better wares. After the soaking and growing in the dike, the bundles are taken out, the lashing cut, and the muddy ends of the osiers washed in a large tub of water standing ready. Then they are carried to the brakes. These are uprights with a narrow slit, at the bottom of which is placed a sharp knife-edge. The operation of peeling is done by placing a single osier rod in the slit, and pulling it quickly and firmly through, the peel falling on one side, the white rod being placed on the operator’s right. The peelers get threepence a bundle for their work, and can peel four bundles a day. We have always seen this work done by women and girls, for though requiring steadiness, not much strength is necessary. The old peelings are kept to protect bundles of ” browns” which have ” weathered” and are ready for the basket-maker. The whites are carefully put into sheds until required. The rods are used for making swills, baskets, skeps (troughs for feeding bullocks), cradles, and perambulators.” pp. 94-5

“Salix viminalis, the basket willow common osier or osier, is a species of willow native to Europe, Western Asia, and the Himalayas.“—Wikipedia accessed 2025