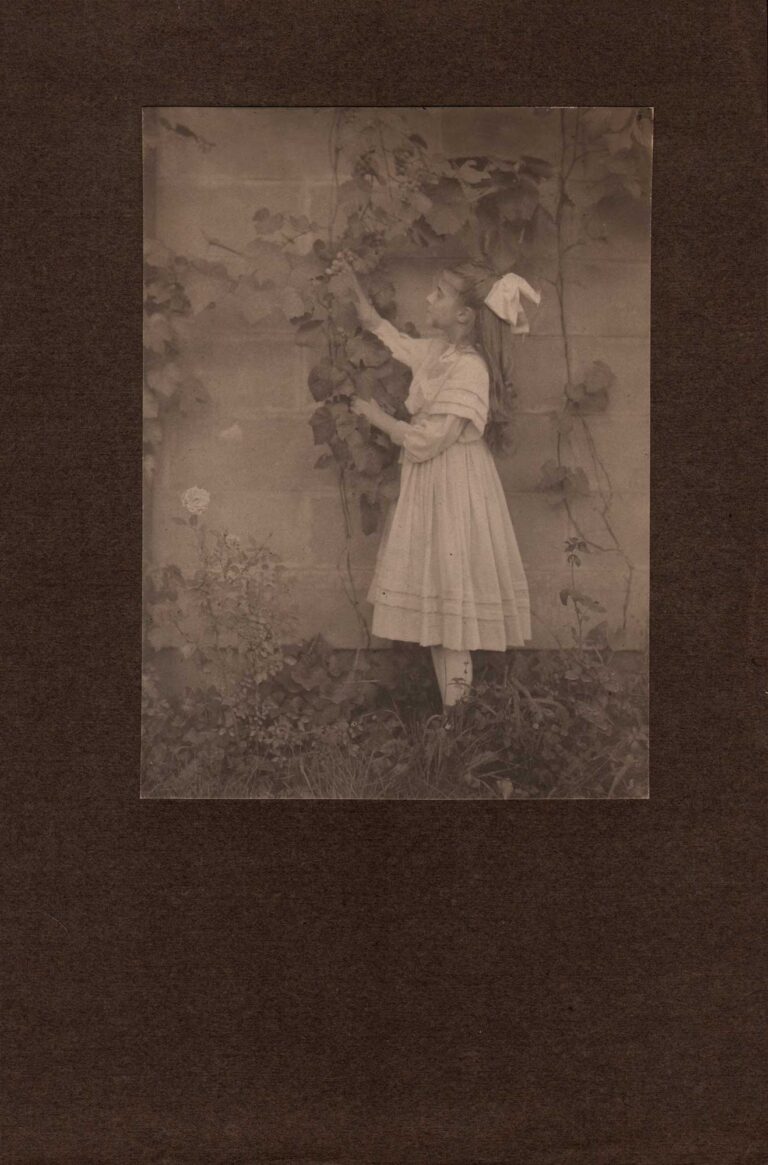

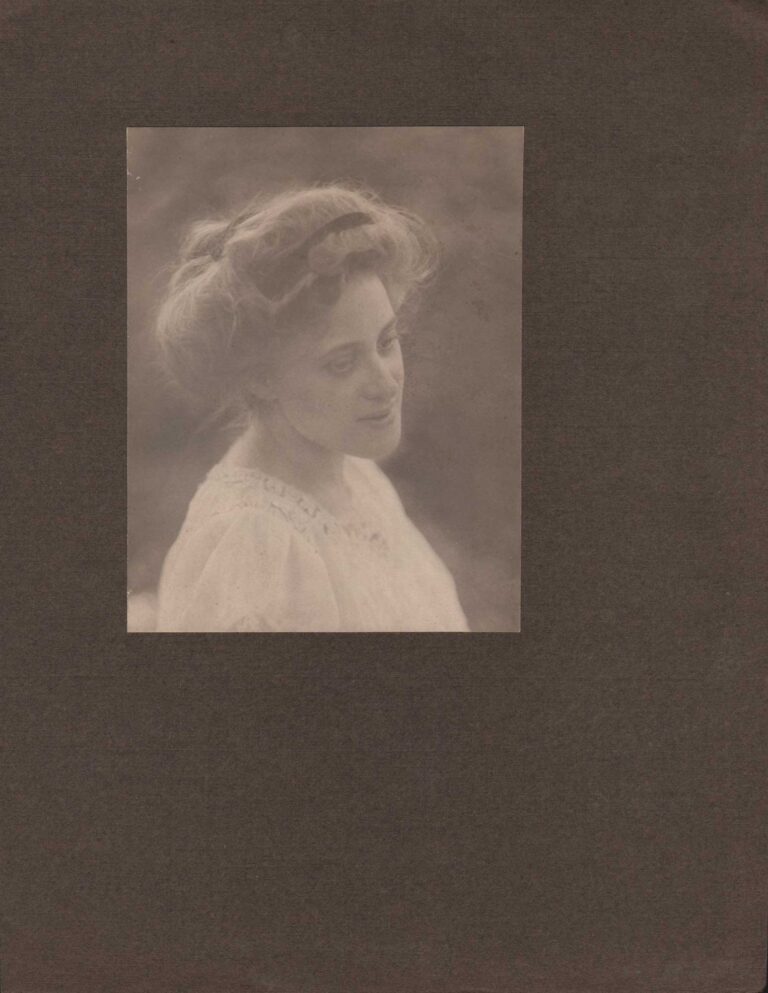

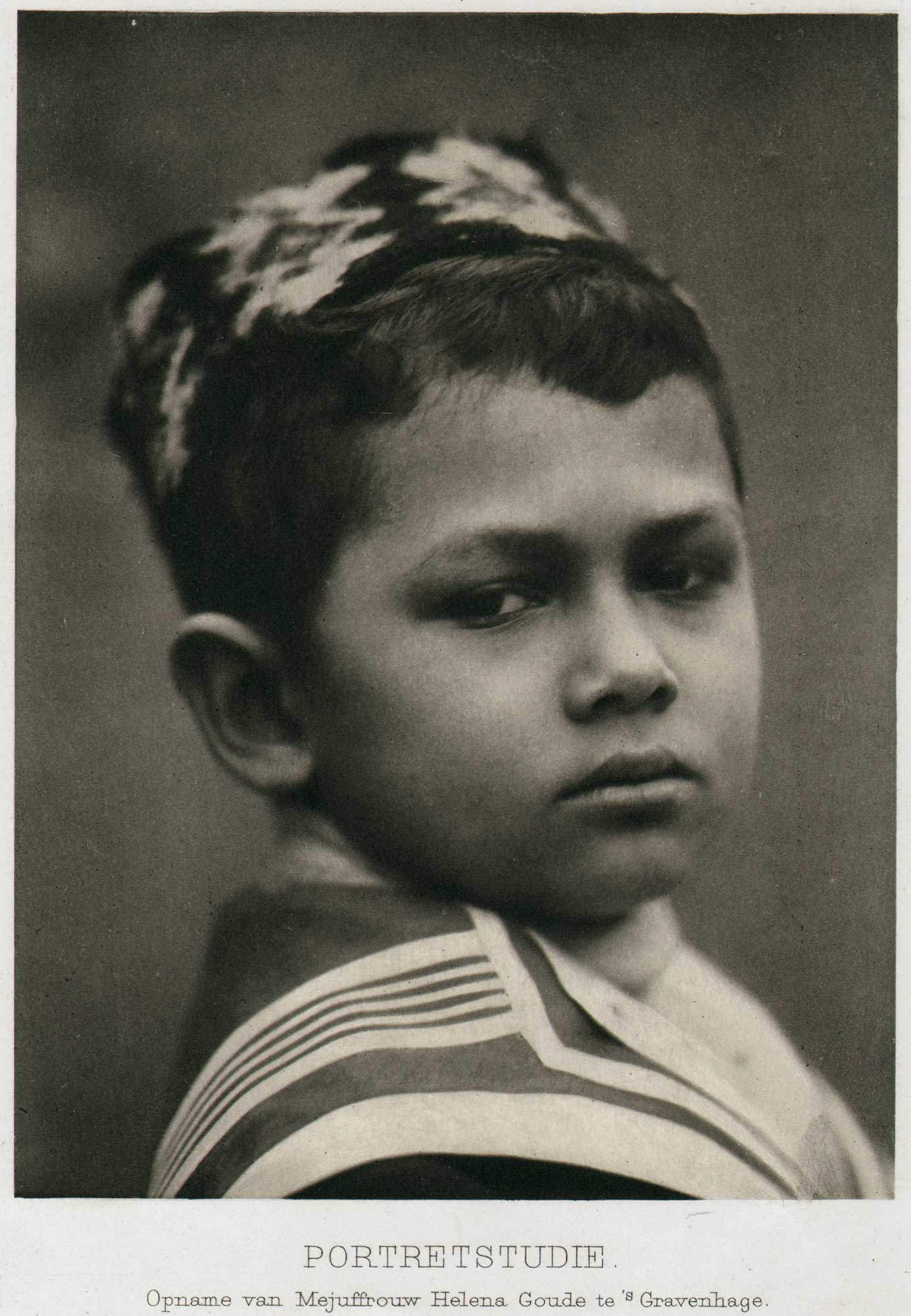

Portretstudie | Portrait Study

The following article appeared opposite this portrait of a young boy.

⎯ Helena Goude ⎯ (translated)

One of our most famous photographers is Helena Goude, of whom we again present a heliogravure in this issue. We mention here some details, which Miss Goude personally shared with us during a visit to her. As is well known, Miss Goude is absolutely not into “template” photography. She has absolutely banned the photographic studio, as we know it, from the moment that portrait photography became a profession. One would therefore look in vain for it in her home. Anyone who wants to be photographed there takes a seat in her conservatory, or in her own sitting room, which is furnished like any other ladies’ salon and otherwise does not differ in any way from an ordinary room.

But it is exceptional that photographs are taken there. The rule is that Miss Goude comes to the person to be photographed with her camera and records him in the environment in which he lives every day.

That this is the right way to deliver a portrait that is more than a copy, needs no argument. Only in one’s own home and environment does one feel and show oneself free and unconstrained and does the photographer have the best chance of being able to notice the characteristic, its of the inner self of his client and that, according to his own opinion, in the image to be able to reproduce; because only through this can a work of art come into being.

Helena Goude chose her profession out of an inner urge to do so. She desired the insignificant existence of a girl who has nothing to do. That photography would provide her with the desired activities was more due to chance and the love for her profession came in practice itself.

It is strange that she, a Dutchwoman, could not persuade any owner of a renowned studio in a capital to take her on as a pupil. Taking on a developed, well-educated young lady as a pupil meant as much as creating a competitor for herself, which will probably have been the reason for many. One of the gentlemen was willing to give her lessons in retouching. Finally she turned to Mr. Bickhof of the A. F. V., who gave her private lessons in photographic technique. Reading the leading magazines convinced her that the direction followed in photographic practice up to that time was not the true one and that the vanity, self-love and bad taste of the public on the one hand and the financial interests of the professional photographer on the other had brought portrait photography into a state of decline and degeneration from which only the new direction, although then still heavily infected with all kinds of extravagances and quackery – after undergoing the necessary purification, could abolish the profession.

When she had been initiated into the secrets of technique, she went to Germany, where people appeared to have a broader view, or at least several great professionals were willing to take her on as an apprentice and she chose Dührkoop in Hamburg, with whose direction she already sympathized. Duhrkoop was one of the first professionals who turned to the new direction and had the courage as a professional photographer to throw the old overboard and introduce the new, artistic portrait, which he succeeded in completely, thanks also to the educational power that at that time emanated from the exhibitions of the, “Kunsthalle” in Hamburg, under Lichtwark, which had convinced a large part of the intelligent public there of the value of the new, more freely conceived art portrait. He made little use of the gum print; for his ideal, the natural and true free, living portrait, he did not need this process.

The carbon print was sufficient for him as a means of expression, and his success was and still is great; his work, because of its simplicity, is enjoyable for everyone and yet it is often a work of art, not least because of that simplicity.

Helena Goude studied with this foreman for half a year and then settled in The Hague in 1904; as a professional photographer. She remained true to her original direction and found herself well there, even as a professional photographer. It goes without saying that this method of photographing often entails extraordinary difficulties and that often quite long exposure is necessary. As an example of this, Miss Goude showed us a very beautiful group of two old people, taken in the conservatory, on one of the darkest, misty days of the year, in November, without using a reflector. The exposure was done with Aristostigmat, full aperture, and lasted a full minute. Yet the persons photographed were apparently not bothered by this. found. The image sharpness leaves nothing to be desired. The shadows were well detailed and the whole soft and harmonious. These soft, transparent shadows are almost never obtained by reflectors, but by very ample exposure and positioning the model at a considerable distance from the window.

Miss Goude usually starts with a normal developer, and forces the development, in the case of moderate overexposure, with bromine-kali. In the case of more overexposure, the plate is placed in an old developing bath, possibly still held back by bromine.

In the case of proven underexposure, the plate is often transferred to a bowl of water and left there to itself, to the extent that, if necessary, is immersed once or more in the original developing bath and then thinned back into the water; a variant therefore on the system of development in very liquids, in a horizontal position, whereby no precipitation on the plate is to be feared, from impurities that may be present in the developer. Most plates are developed for a proof on celloidin paper and later reinforced, in order to give them sufficient coverage for the carbon print. Retouching is forbidden in her laboratory, with one sensitive plate exception of which is the removal of small factory errors etc. The main subject in her studio is the carbon print, which Miss Goude considers to be our most beautiful process, and in that opinion she completely agrees with her teacher Dührkoop. That does not, however, alter the fact that she also works with matt albumin and matt Bosch paper. In her working method, as we see, there is nothing extraordinary; nevertheless we thought it would interest the readers to know, by what means and by which means, of the many existing ones, one of our best workers achieves her excellent results.

And Miss Goude is satisfied with her success with modern photographic portraiture. Up to now she has worked entirely alone, but can hardly keep this up. If the work continues to increase, she will be forced to seek help, which, however, is not easy to find in her profession and in her efforts, all her work, from beginning to end, is too personal for that.

For a time she had as a pupil a young German lady who, being in the profession, gave up template photography by reading Loescher’s Camera-almanaks, and came to her to learn modern portrait photography. (pp. 41-43)

Helena Aleida Goude: 1868-1951

Helena Goude was born on 9 December 1868 in Amsterdam. She was trained by photographer Joh. Bickhoff (1881-1968). As a photographer she mainly made portraits . Stylistically she belonged to the group of art photographers or Pictorialists . Like Wieger Idzerda she worked for some time with the German photographer Rudolf Dührkoop in Hamburg . Helene Goude was a member of the Dutch Club for Photo Art (NCvFK) and of the Dutch Amateur Photographers Association , the NAFV. She was also the only woman on the first board of the Association for the Development of the Sense of Beauty in the People , called Art to All , which was founded in The Hague in 1907. – Wikipedia