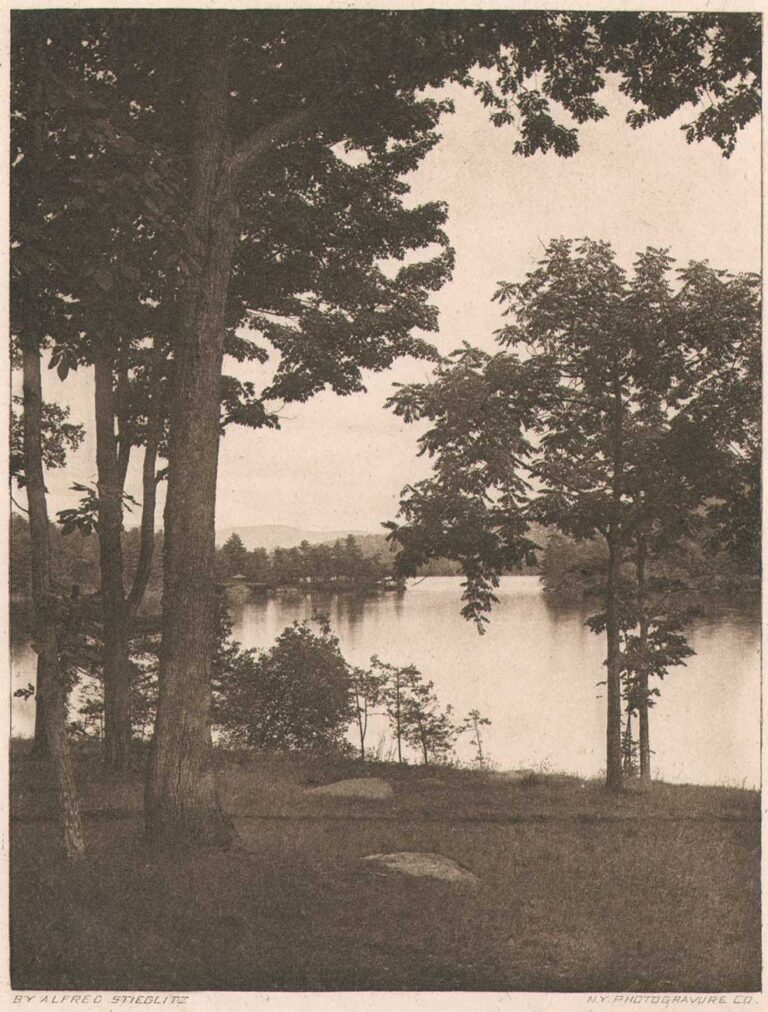

Reflections

Commenting in the accompanying catalogue letterpress, Henry Peach Robinson writes of Lyddell Sawyer’s work and this plate:

Comparatively young in years, but old in the accomplishment of good work, Mr. Lyddell Sawyer is one of the masters, and a frequent and multitudinous exhibitor. Indeed, so fruitful is his fancy and unerring his hand, that he sometimes makes the mistake of sending too many pictures-an error frequently made by a young exhibitor, but of which so old a hand should not be guilty. It is not that the work is not worth exhibiting, but-to let the public into the secret-too much thought by an original thinker makes thinking too cheap. Mr. Sawyer is one of those rare photographers who have ideas before they begin to embody their creations. Of late we have had too much embodying and too little thought, too much manner and too little matter, and clouds of words to hide the absence of ideas, or to prove that ideas had nothing to do with art. Mr. Sawyer has always something to say worth saying in his pictures, and he almost always says it well; at other times perhaps a little carelessly. These slight lapses are, we know, due to the very short time this true artist can devote to art production; but such a fertile brain and skilful fingers could afford to suppress all but the best. Their would be quite sufficient left to give character to an exhibition even then. These remarks apply with more appropriateness to former exhibitions; in the present he shows a few pictures only, and these, for original inspiration-that first principle of art which is often absent-and perfect carrying out, surpass anything in the gallery, and worthily occupy the place of honour. These grand pictures have all the effect of candle-light, and the effects massive and luminous, the lights brilliant, and the shadows transparent. In noticing any pictures in which strong effects of light and shade are prominent, it is usual with critics to refer to Rembrandt-often very wide of the mark; but here we have photographs in which the true principles of Rembrandt are embodies. A good deal of discussion has arisen as to the means by which these pictures were produced. We do not agree with those critics who judge by process instead of result, and are convinced that minute analysis of “how it is done” soon dissipates any poetry that may be in a picture. We are content to know, as the conjurer says of his tricks, “Some people say they are done somehow; others that they are done in a different way altogether.” Although all are good, we think Reflections (78) (see illustration) and The Last Rehearsal (79) the best. We could have spared A Disciple of Diana (75) and its companion, Vanity (85). The disciple is represented as a muscular young man; yet we thought that the followers of the huntress goddess were all nymphs! In The Toper (81) the masterly treatment does not compensate for the repulsiveness of the subject. Nevertheless, well done, Mr. Sawyer! we expected great things of you, and you have “arrived.”

We have given considerable space to a consideration of these remarkable pictures, because for novelty and power there is nothing to compare with them in the room How they escaped a medal is one-but not the only one-of the mysteries of this year’s judging.