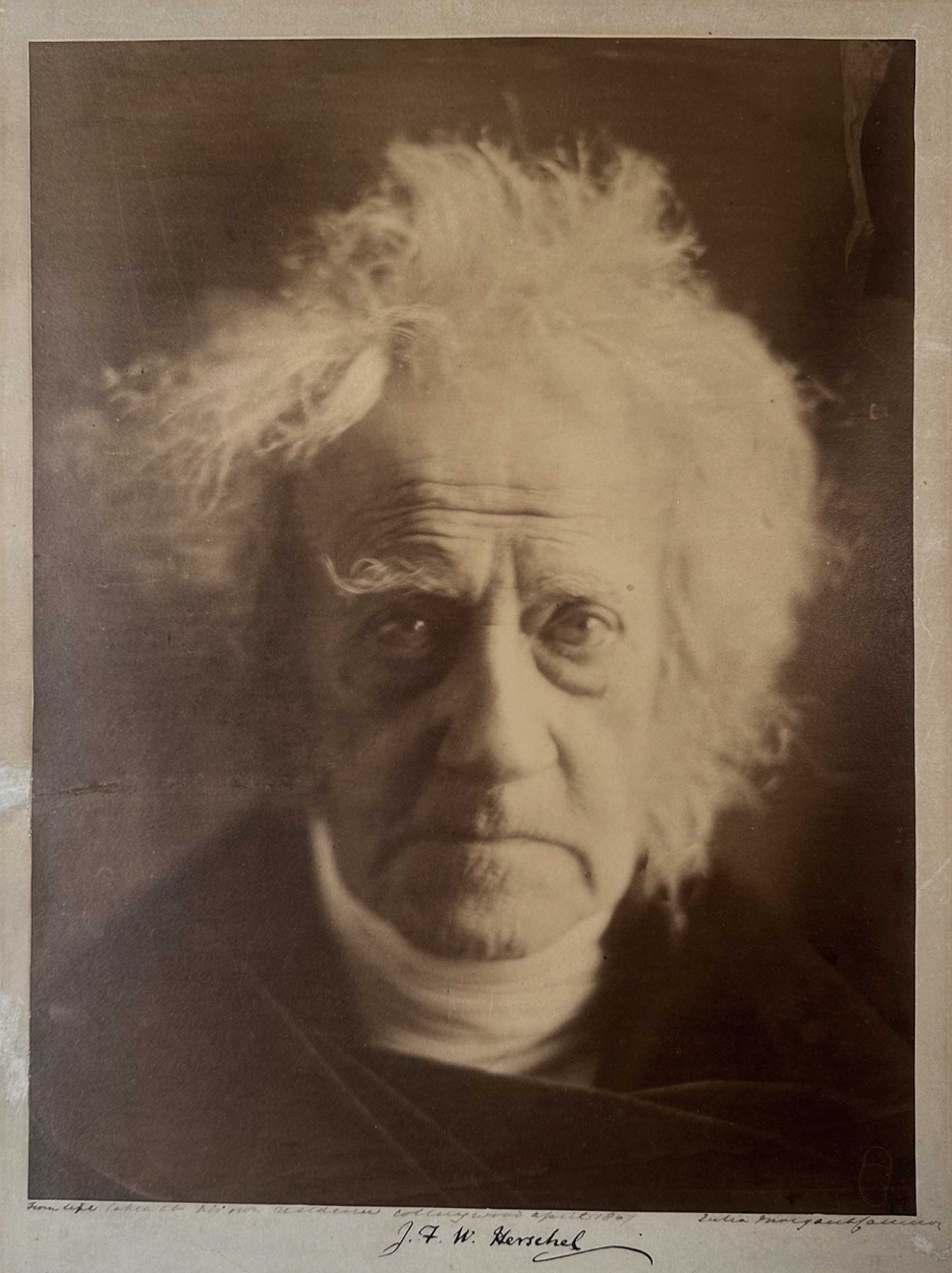

Sir John Frederick William Herschel

“They are not only From the Life but to the Life and startle the eye with wonder & delight. I hope they will astound the Public & reveal more of the mystery of this heaven & our art – They lose nothing in beauty & gain much in power”

The above quote is attributed to Julia Margaret Cameron, (1.) when writing to her good friend Sir John Frederick William Herschel (1792-1871) in 1866. Cameron was speaking of resulting photographs she had taken a year earlier after having purchased a large format camera. She had made the decision after having been influenced by another close friend, the British painter and sculptor George Frederic Watts. He recommended she take a series of so called life sized heads– her own take on photographic portraiture- while first pursuing her craft as an aspiring photographer at 48 years of age- only two years after 1863, when her daughter and son-in-law gave her a sliding-box camera for Christmas. (2.)

One year later, in April of 1867, she achieved the result seen here. His white hair tousled and left uncombed after reportedly instructed by Cameron to first wash it for the sitting at Collingwood, his home located near Hawkhurst in Kent, the resulting work as a portrait reinforces those ideals penned in her 1866 letter to Herschel: indeed, the brooding and mysterious nature captured by Cameron’s lens suggests a symbolic likeness of a man whose own life was spent on a perpetual quest for discovery and explanation of the unknown.

John Herschel–famed mathematician, astronomer, and for our purposes here, photographic pioneer–is one of the unsung heroes of what we know as modern photography: pre-digital of course. For those old or lucky enough to have worked in a wet darkroom, it was Herschel the scientist and chemist who discovered and corresponded with William Henry Fox Talbot that sodium thiosulphite, commonly known as “hypo”, could “fix” silver halides, and therefore was a reliable means of making a photograph permanent. Herschel is even credited with coining the very word “photography”, along with the terms “negative” and “positive” pertaining to photographic negatives and prints. In 1842, he also invented the cyanotype, or blue print process. You can learn more about this beautiful medium from our 2016 blog post as well as see nearly 175 examples on PhotoSeed.

Buried next to Charles Darwin and Sir Isaac Newton in Westminster Abbey, Herschel’s genius was an ability to make science understandable to both the curious and the more educated through his writings and presentations to the established scientific bodies in the early through mid 19th century.

Of particular note, this rare surviving example of John Herschel’s “head” portrait by Cameron pertains to its provenance. Before gifting it to a private individual in 1981, it was owned by Angelica Garnett, (née Bell 1918–2012). Her great-great aunt was the photographer of this work, Julia Margaret Cameron. A progeny herself of the English Bloomsbury Group of writers and artists, her aunt was Virginia Woolf- sister to her mother Vanessa Bell, a Bloomsbury artist whose own grandmother was none other than Julia Jackson, sitter for several of Cameron’s most successful portraits. In her book Deceived With Kindness- A Bloomsbury Childhood , (Pimlico: 1984 with new preface edition, 1995) Garnett writes in the prologue about Cameron’s influence:

“In the passage at Charleston I had hung some photographs of my grandmother, Julia Jackson, taken by my great-great aunt, Julia Margaret Cameron. As I looked at them I became conscious of an inheritance not only of genes but also of feelings and habits of mind which, like motes of dust spiralling downwards, settle on the most recent generation. Vanessa shrank into a mere individual in a chain of women who, whether willingly or not, had learnt certain traits, certain attitudes from one another through the years. One of these was clearly seen in a snapshot that always stood on Vanessa’s writing-table, and which I now keep in the same place, of Julia in profile looking out of the window.” (p.12)

It’s perhaps not a surprise that photographic snapshots by an amateur and masterful portraits by the hand of someone as esteemed in the history of photography as Cameron several generations removed might have preserved human qualities for posterity for someone in the same bloodline. In light of her ancestor’s likeness of Herschel, this portrait would have no doubt also have spoken on another level to Garnett, offering a key perhaps in discussing similar ideas swirling around authenticated inheritance and meanings derived from photographs.

1. Quoted in Hamilton, V., Annals of my glasshouse, Claremont, Scripps College, 1996, p. 31) as listed with sale description for this photograph: Stewart & Skeels: #4: firsts rare book fair: twenty-three highlights 2023.

2. The Art Story: Julia Margaret Cameron