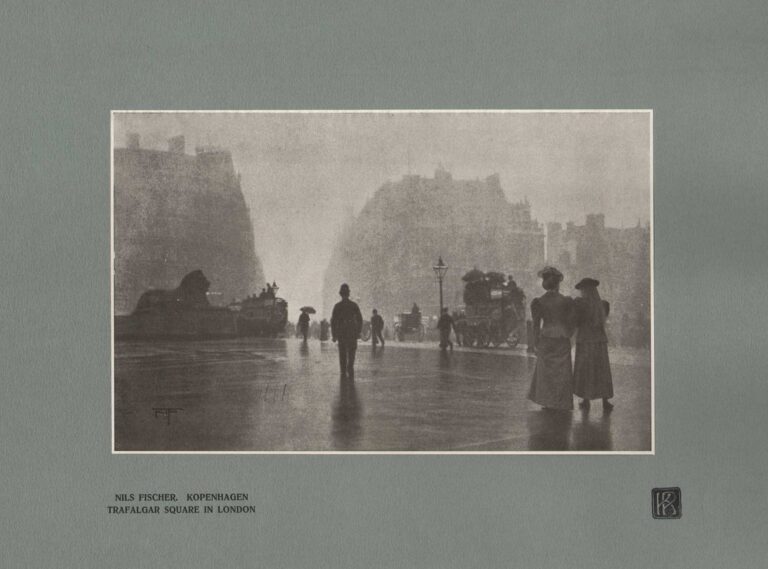

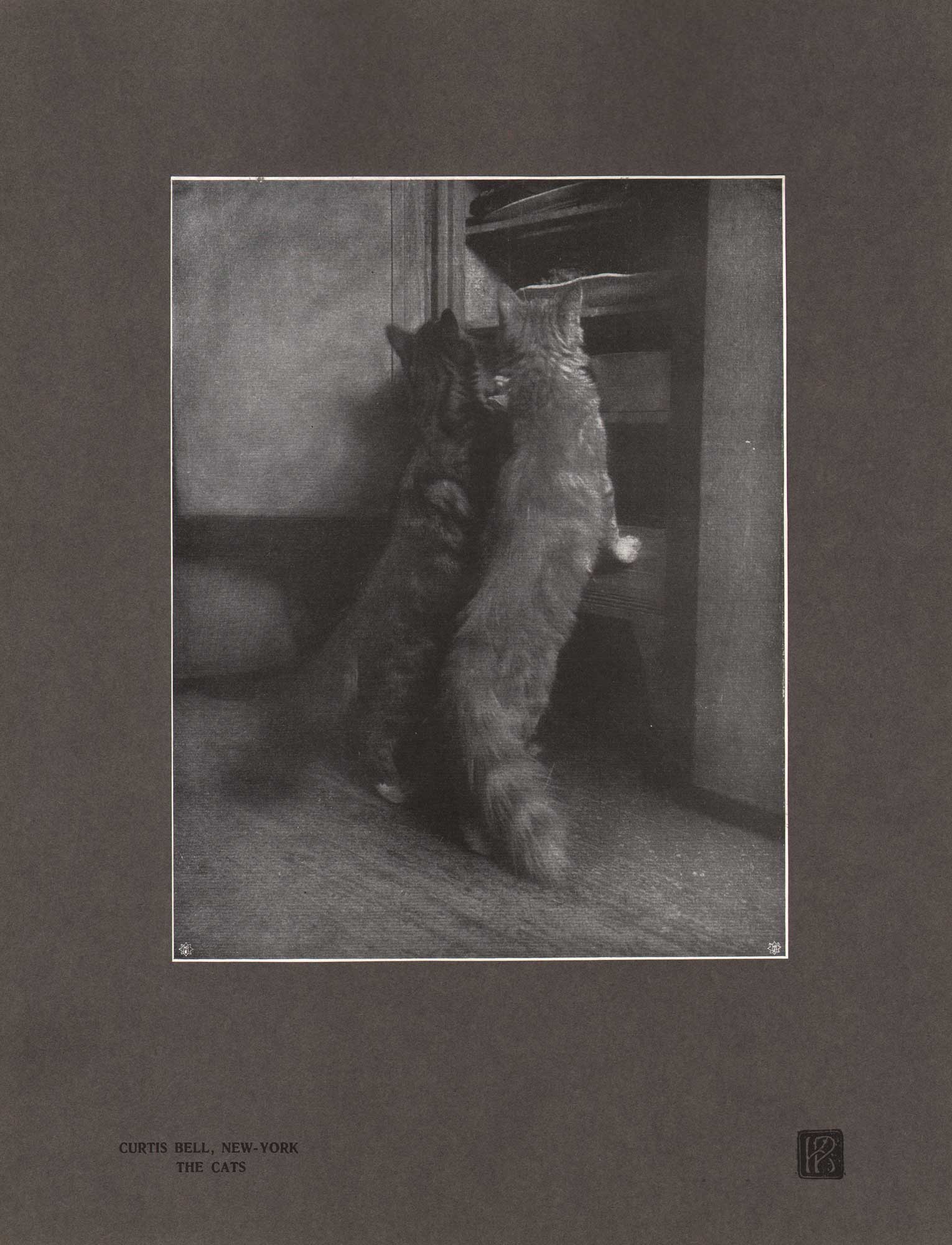

The Cats

Mr. Bell’s “Ravvy & Caddy” is one of the popular pieces in the gallery and represents two cats of high degree reaching for some tempting dish upon a pantry shelf. A duplicate of this picture was purchased at the Chicago Salon by Mr. F. Dundas Todd. (1.)

Mr. Curtis Bell sold his “Ravvy and Caddie” three times at the Chicago Salon, solely, I presume, because the price was only $15 per copy. And it seems to me more logical to sell a print three times at a reasonable figure than not at all at a presumptuous price. The privilege of considering it worth a large sum of money can, after all, be not such an edifying one, as long as one finds nobody to share one’s opinion.

The only way to approximate a market value of pictoral prints is to investigate how much they might bring on the average, if offered for sale as illustrations. There is lately a decided demand for photographic illustrations, and consequently a certain standard price in vogue. (2.)

- Excerpt: The First Minneapolis Photographic Salon, Western Camera Notes: A Monthly Magazine of Pictorial Photography, March, 1903, p. 65

- Excerpt: Sidney Allen, What is the Commercial Value of Pictorial Prints? The Photographic Times-Bulletin, December, 1904, p. 539

✻ ✻ ✻ ✻ ✻

Thomas Curtis Bell: 1865-1927

In the history of Photography, Curtis Bell is largely unknown today, although at the beginning of the Secession and Pictorial Photography movements in the U.S., he played the very active, and public role, as naysayer and foil to its lofty ambitions. If one were discussing the emergence of the Photo-Secession in 1903-04, the first years Camera Work was published, the name Curtis Bell would have been offered up in refuting the aims of that esteemed journal’s advocacy for a new school of American pictorialism. Here’s an example of Bell playing the foil in 1903, when his two-part series, the “Pictorial Treatment of Interiors”, was published in the September and November issues of The Photographic Times-Bulletin:

PICTORIAL treatment is an elastic term. Art itself is “but a matter of opinion, and nearly every form of Art expression has had its period of domination and decline. There were good pictures before the present modern school was heard of, and some of the work of Angelo, Rubens, Giotto and others will compare favorably with that of Whistler, Daubigny and Steichen.

The late dictators of the photographic salons and magazines were extreme impressionists, and to claim any pictorial quality for brilliant and well-defined photographs brought sneers to the lips once so voluble, but now so calm and still. Nevertheless, I venture to head this article ” Pictorial Treatment of Interior Photography,” in the conviction that the recognition is at hand of other qualities than ” breadth,” “suggestion,” “atmosphere,” and the other fakeries that have enabled blunderers to pose as leaders. (September: p. 401)

As every political party needs an adversary, apparently early photographic movements did as well. His “late dictators of the photographic salons” was a direct insult to Stieglitz and those who thought like him, making Curtis a rabble-rouser for his time in attacking and questioning the seemingly new direction embodying pictorialism.

Today, if we remember anything of Bell’s role in all this, it would be his presidency of the Salon Club of America. Writing in 1996, photographic historian Gary D. Saretzky does a concise job of outlining this role, which lead to the 1904 First American Photographic Salon– the name itself co-opting and a way taunting the ambitions of the Photo-Secession:

By the end of 1904, there were about two dozen “Active Members,” including (Elias) Goldensky and Rudolf Eickemeyer, Jr. The original purpose of the Salon Club, founded in December 1903 as an alternative for photographers excluded from the PhotoSecession, was to circulate portfolios of the members’ prints among themselves for written critiques. However, under Bell’s leadership, the Salon Club joined and then dominated a new organization, the American Federation of Photographic Societies, which, also led by Bell, organized the first major international exhibition of photography to be held in New York, known as the First American Photographic Salon. Although Stieglitz and the Photo-Secession boycotted the show, which opened in December 1904, 10,000 photographs were submitted to the judges by hundreds of photographers and tens of thousands attended the exhibit. (1.)

In the volume The Valiant Knights of Daguerre, published in 1978, editors Harry W. Lawton and George Knox gave this summary: “most of the critics found the exhibition of mediocre quality”- in commenting on this First Salon, held in New York in December, 1904. In total, this new school would feature 10 American Photographic Salons held throughout the US from 1904-1914, according to secondary sources, all conducted by The American Federation of Photographic Societies, typically in spaces at art museums. Bell’s involvement doesn’t seem to go beyond a few years after the Salons began-his own professional aspirations with a new bespoke studio on Fifth Ave. established in 1906 taking up the majority of his time.

But at the outset, writing in July, 1904, five months before the opening of the First American Salon, prominent art critic Sadakichi Hartmann seemed delighted in his role as instigator, stirring up a feud on the pages of The American Amateur Photographer between the two camps lead by Stieglitz and Bell, going as far as suggesting a dual:

All this sounds like open revolt! But far from being lawless, it is merely the expression of new laws. For each generation there is a different standard. Old forms and old perfections wither. Out of the old symbols the color fades day by day, and it is the younger generation’s business to create new ones.

It nevertheless sounds like an open revolt. And there may be an opposition! A duel between Messrs Alfred Stieglitz and Curtis Bell would prove indeed a great attraction. There are none upon whose swordsmanship I trust more surely than that of these two gentlemen. It will stir up the stagnant waters of pictorial photography — they surely need it — and make us all more happy at the end. (2.)

A Truce, of Sorts

Weighing in on all of this- certainly as a way to not offend their subscriber base who did not buy into the arguments of one camp versus the other- were the editors at The Photographic Times. In August, 1905, they declared a truce of sorts by writing:

WE wonder if the professional photographer really needs to be warned against Sidney Allen, (Sadakichi Hartmann-editor) or if the majority of the readers of photographic publications care a rap for such matters, or the vast amount of spleen vented through the columns of the photographic press during the last twelve months.

Are they not more interested in things truly photographic and not at all interested in photographic politics?

How about it?

If the American Salon helped to bring your work into notice and afforded you the opportunity of seeing the work of your associates and enabled you to assimilate many good ideas, do you care if Curtis Bell did get a good bit of popularity from the whole thing?

If Alfred Stieglitz chooses to bring his associates into close relation with himself and exhibit their work as a body and refuses to mix with the rest of us, so long as the pictures are really good and teach you a valuable lesson, do you care if he won’t play in your yard?

You certainly don’t; you are interested in photography, the simon pure article, sans politics and petty squabbles, and subscribe to a photographic magazine for photography.

We know we mixed in politics last year; it was a mistake, and we admit it; no more for us. Hereafter if any one heaves any mud at us, we will dodge, and endeavor to give you a good straight photographic magazine, up-to date and in the interests of all without prejudice. (p. 374)

Curtis Bell: Enigma

For someone as prominent as Bell, it was surprising to this archive that not much detail of his life could be gleaned from secondary sources. Even basic information regarding his family, when he was born, where he was from, and when and where he died were complete unknowns. Even the Saretzky essay on Elias Goldensky quoted above had it wrong on where Bell was from, calling him “a Midwesterner who opened a portrait studio in New York”. So we will break a little ground with this overview, but many details may be lost to history.

The first revelation? Bell’s birth name was not Curtis but Thomas. Born in Orleans County, New York in 1865 (3.) and raised in Albion, 35 miles northwest of Rochester, he adopted his preferred professional name of Curtis from his mother’s surname: Emily Cleomira Curtis Bell (1839-1918). His father, Major Thomas Bell, (1837-1900) who had fought valiantly in the Civil War battles of Harper’s Ferry, Antietam, and Chancellorsville, was inspector of customs at the New York Customs House beginning in March, 1871 and lasting for many years. A leading Republican of Kings County, N.Y., his biography stated “He was prominent in all matters pertaining to the best interests of the old soldiers.”…and “In connection with Joseph W. Kay and Benjamin F. Tracy, he secured the introduction of the article in the United States law giving veterans the preference in all civil service appointments. This is one of the most important measures for the soldiers that has been secured since the Civil war.” Interestingly, a biography of Major Bell appearing in the 1902 volume A History of Long Island revealed he also enjoyed the stage, acting for two years before the war with Edwin Booth’s theatrical company, and was a “ fluent, forceful and sometimes very eloquent public speaker”. Perhaps these same traits were inherited by his future son as public foil to Stieglitz and the personable owner leading a fashionable New York City Fifth Ave. portrait studio.

Curtis Bell’s formal secondary education- if any- is unknown, although its assumed he received his primary education in the Brooklyn public schools, his family living there since 1871 after the death of his mother’s father Hiram Curtis in 1870. (4.) The photographer would marry twice, although only the details of his first marriage and name of his second spouse have been discovered as of this writing. On June 5, 1888, he married Kathleen “Kittie” Euren Tifft (b. 1868) in Vernon, N.Y. (approx. 35 miles east of Syracuse) by Rev. Stephen F. Holmes. The couple then residing in Brooklyn, N.Y. (5.)

It’s possible Curtis Bell did not go to college, and instead got started in business by gaining patronage employment through his father’s well-connected position as inspector of customs at the New York Customs House, then located in Manhattan at the Merchant’s Exchange Building at 55 Wall Street.

Regular Business & Photographic Beginnings: Inspirational Spouse?

Jumping back to his amateur photographic interests, the earliest reference to Curtis Bell seems to be a notice in the December, 1900 issue of Anthony’s Photographic Bulletin, which published he had won 10th place and $5.00 for his entry for “best photographs of the best subjects” in a contest sponsored by The Security Trust and Life Insurance Company for their future 1901 calendar. He also secured an honorable mention in a contest sponsored by the Boston-based Youth’s Companion magazine, in their 1902 Christmas day issue. (p. 675)

But an interesting twist: could the future professional photographer’s wife have given him needed inspiration to try his own hand in the medium? This is because we find that in November, 1900, “Mrs. K.T. Bell” won the 8th prize in Pearson’s magazines Photographic Competition, receiving a $10.00 check for her efforts, a contest which originated as early as July, 1900 according to the fine print listed with the winners list for the November issue. Her address as printed in Pearson’s was 558 Fifth Ave. in New York, one with a superb artistic pedigree: New York’s Lotos Club was headquartered there (Curtis Bell was a member) as well as the art galleries for M. Knoedler & Company at 556-558 Fifth ave.: the former longtime tenants during this era.

After his father, Major Thomas Bell died in November 1900, the future professional photographer undoubtedly came into some money after his estate was settled. However, in discussing his talents for interior photography, the December, 1903 Photographic Times Bulletin made clear Bell the younger still made his living outside the medium: “Mr. Bell is an amateur photographer, engaged every day in business, and has been able to devote only his spare time to photographic work.” This daily employment revolved around the legal profession, to some degree, with several yearly annuals of Bender’s Lawyers’ Diary and Directory for the State of New York listing Thomas Curtis Bell a notary public from at least 1901-04, his listed address as 558 Fifth Ave., and his term expiring on March 30, 1904.

Undoubtedly however, he was earning something for his photographic efforts as a side hustle. The circle of powerful political and influential social acquaintances from his late fathers orbit certainly bore fruit for Curtis Bell: several of the interior photographs used as illustrations for his December 1903 article in The Photographic Times-Bulletin featured rooms in the mansions of New York Tribune owner Whitelaw Reid (1837-1912) and attorney, businessman, and Republican politician Chauncey Depew. (1834-1928) Bell would have surely been paid for his efforts for these complex, technically lighted photographs, with the successful results a natural way for him to create a running list of future clients.

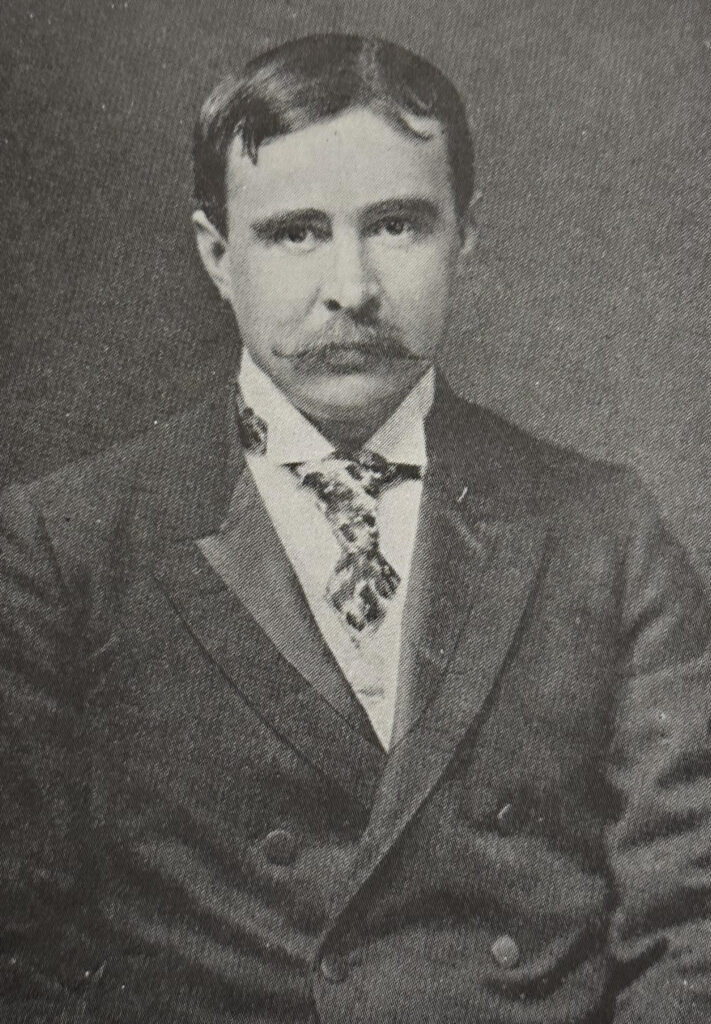

A formal portrait by J.C. Strauss of Bell, taken around this time as chairman of the Salon Club, (ca. 1904-06) shows a nattily dressed, mustachioed gentleman with straight, slicked hair and cowlick. Sporting a double breasted suit and floral tie tucked within his white shirt and set off by a fashionable collar, (6.) he certainly portrayed himself as confident in his own looks with the proven track record he wasn’t one to back down from a verbal fight in the photographic press.

Portrait of Curtis Bell, ca. 1904-06: Chairman of the Salon Club, by J.C. Strauss (1857-1924)

Besides the new role Bell found himself in leading the Salon Club and the American Federation of Photographic Societies beginning in very early 1904, he was busy winning multiple prizes for his amateur work that year. Still using his 558 Fifth Ave. address, the head of the new American Photographic Salon is listed as winning the following prizes in the $500 Competition as printed in the August, 1904 issue of The Photo-American: Sixth place prize in genre class for a photo of two felines: “Ravvy and Caddy”, 12th & 13th places for “An Ardent Courtship” & “After the Bath”; & 23rd place for “Mischief”. In the Portrait class, Bell won 8th place for “The Managing Editor” and the First place prize in the Popular class for “In the North Woods”; 8th prize for “Dining Room of Senator DePew”, 14th prize for “The Sun-Shower” & 33rd prize for “A Memory of Boyhood”.

In 1906, Curtis Bell would open his first known professional portrait studio in 1906 at 588 Fifth Ave. in New York City. He would move the studio several times during his active involvement until 1921, when he tried selling controlling interest in the business- unsuccessfully- to the noted American portrait photographer Charlotte Fairchild (1876–1927) that year. A complicated scheme in which the over-leveraged Fairchild was sued by a supposedly “intimate” friend by the name of Alice King who claimed she had tried to help Fairchild purchase the Bell studio with funds of her own ensued. Bell would eventually testify as a plaintiff witness for King, in a February, 1925 jury trial in the New York Supreme Court’s County Court House in Manhattan. King sought $15k in damages for her aforementioned role in the studio purchase. She had brought the court action against plaintiffs Charlotte Fairchild, Inc. (a photographic studio) and Col. Arthur W. Little, a printer and bookbinder, who represented Fairchild’s interest, but King ultimately lost the case.

Curtis Bell may well have turned the daily operation of his studio over to others by 1922, the year the lawsuit was first initiated, but his name was still affiliated with it after the conclusion of the case, by late February, 1925. In October of that year, the New York Evening Post ran an advertisement: “A Gift for the Bride”, trumpeting the studios photographers as “Artists in Photographic Portraiture” …” “It has been our privilege to photograph as brides many of the socially prominent matrons of today”.

Although Bell died at his home in Yonkers, New York on December 17, 1927, Curtis Bell, Inc., the studio, would see its name in print through 1929. (7.) It would seem that ultimately, a 20 year lease for the Bell studio signed in 1919 could not save the enterprise, nor its paying roster of socially prominent clients from the ravages of the American stock market crash in October, 1929 that brought about the Great American Depression.

Timeline: Curtis Bell & his New York Studio

1901: Bell exhibits in the Philadelphia Photographic Salon.

1904: Notice in The Ontario County Times, Canandaigua, N.Y. on May 4: “Thomas Curtis Bell, of New York city, but formerly of Albion, has been appointed as judge of paintings at the St. Louis exposition.”

– 558 Fifth Ave. Entered work in Royal Photographic Society Salon: London: Forty-ninth Annual Exhibition of the Royal Photographic Society of Great Britain: two entries:“In the North Woods”, “Raddy & Caddy” (sic)

1905: 558 Fifth Ave. Entered work in Royal Photographic Society Salon: London: Fiftieth Annual Exhibition of the Royal Photographic Society of Great Britain, two entries: “Threatening Weather”, “In June”.

1906: This was the first year Bell re-located his studio to 588 Fifth Ave., where its believed his new commercial studio debuted. Last year he would enter work in the Royal Photographic Society Salon: London: Fifty-first Annual Exhibition of the Royal Photographic Society of Great Britain, One entry: a pastoral landscape: “Woodland Mist”.

1908: Gets conned out of $200 in his studio but police arrest suspect after he got wise to the scam: From The Evening World, 18 March, it was reported a dapper man impersonating a rich and famous horse jockey: “Jack” Martin, entered the Bell studio at 588 Fifth Ave. and said he wanted to order $1600 worth of life-size photos of himself. Martin’s “Betting commissioner”, in on the con, comes up to the studio after making a call to Bell and says he has a “sleeper” in the second horse race at New Orleans. A gullible Bell proceeds to wager $200 on the inside advice-giving his money to a complete stranger. Not surprisingly the horse lost the race, but the photographer got wise and had plain-clothes police waiting behind a studio screen when “Jack” showed up again the following Monday morning. After being arrested by two plain-clothed policemen hiding behind a studio screen, the conman said his name was Charles Morton and was remanded to a Grand Jury on charging of impersonating another and obtaining money ($200) on false pretenses. Moral- according to the last line of the article: Write your own (betting) tickets.

1909: The article “The Photographer’s Metropolis” by an anonymous writer describes the Bell studio and robust Fifth Ave. neighborhood lined with studios, including those of Clarence White, Gertrude Kasebier and Stieglitz’s own Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession in Abel’s Photographic Weekly 3 (Jan. 16, 1909 1:74-75).

1913: Curtis Bell Studio advertisement in the New York Sun on March 9:

ONLY a small number of those who could well afford it availed themselves of the opportunity to have their portraits made by Gainsborough or Van Dyck | Many patronized other painters whose names and work have perished.

The work of Curtis Bell bears the same relation to that of other photographers as that of Gainsborough and Van Dyck to their contemporaries. There is in it a strength and refinement an aristocratic air-strongly appealing to people of discrimination.

Those who appreciate Art -and an emphasis of that which is most beautiful, attractive and refined in the subject- should make themselves acquainted with his work. One does not receive the continued support of the most cultured and distinguished element in American society without reason.

Curtis Bell Studio

AT 588 FIFTH AVENUE

Near 48th Street

– Another advertisement from the April, 1913 issue of Vogue:

Curtis Bell’s Portraits

of Women and Children

Those who appreciate Art-and an emphasis of that which is most beautiful, attractive, and refined in the subject should make themselves acquainted with his work. There is in it a strength and refinement–an aristocratic air- strongly appealing to people of discrimination. One does not receive the continued support of the most cultured and distinguished element in American society without reason.

CURTIS BELL

PHOTOGRAPHER

AT 588 FIFTH AVENUE

Near 48th Street

– Almost Drowns- from The Bulletin Of Photography: August 27, 1913:

Curtis Bell, the well-known New York photographer, and a party consisting of his wife and four other ladies, had narrow escape from drowning on August 10th, when his forty-foot yacht was driven on a rock during a storm which came up suddenly. Aid from nearby boats came just before Mr. Bell’s yacht went down. p. 280 (the accident occurred of the coast of Greenwich, CT: The New York Times also reported the accident August 11)

1914: Bell studio listed in the American Art Directory, vol. 11 under heading: Who’s Who Among Art Dealers: New York City, an indication he may have earned income from copying traditional works of art.

1915: Notice in Bulletin of Photography on January 27 he had moved his studio from 588 Fifth Ave. to 616 Fifth Ave.

1918: His business is incorporated, as reported from the state capitol of Albany on October 25: Curtis Bell, Manhattan, photographic and works of art, $15,000; A.E. Boyd, E.A. Stout, B.H. Koehler, 7 Wall St. (in the 1925 court case, Robert Koehler, a lawyer, would testify he owned 40 shares in Curtis Bell, Inc. and he was treasurer of the corporation)

1919: New studio space and lease for the photographer at 620 Fifth Ave. reported in the New York Sun on July 1: …”also to Curtis Bell, top floor and pent house for $45,000” (this indicates a very long lease- 20 years as it turned out as Bell testified to in court in 1925.

1921: Bell sells controlling interest in his Curtis Bell, Inc. studio to Alice King on behalf of Charlotte Fairchild, Inc.. But first, as reported in New York Times on March 8 under (business) REORGANIZATIONS: Curtis Bell, Manhattan, carry on business with $15,000 and 110 shares preferred stock, $100 each; 300 common, no par value. (this would be his own separate business)

1923: Sunday, February 11: from the New York Times: “at the International Photographic Arts and Crafts Exposition to be held at the Grand Central Palace in New York City from April 21 to 28: Professional photographers, including Anna Donahue Studios, Curtis Bell Studios, William Hollinger Studios, Henry Havelock Pierce Studios and John D. Scott Studio are preparing special exhibits.”

1925: Drama & Death in and Around Bell Studio: On February 4, a fire, believed to have originated in electrical wires in the basement of 620 Fifth Ave., causes the death of New York City fireman Lieut. William R. Fletcher and the rescue of seven women and one man. Three hundred workers in the building at 618-620 Fifth Ave. occupied by Dobbs & Co. escape the flames, mostly women garment workers for the fashion house Bergdorf & Goodman, with damage causing upwards of $1 million in losses. A New York Times article noted the sixth floor of 620 was occupied by “two photographers, Curtis Bell in front and Michael Gallo in the rear.” A follow-up article the next day in the Times revealed the fireman died trying to save Gallo, “who had been trapped on the top floor of the building. This became known yesterday when Michael Gallo, photographer, told how Fletcher had rescued him. Gallo was in the darkroom of his studio on the sixth floor of 620 when he heard excited voices outside. “I came out and found the girls and those employed by Curtis Bell on the same floor, hurrying to the fire-escape,” said Gallo. “They all got out there, probably fifteen of them, when they discovered there were no ladders going either up or down. They could not stay there as the smoke was very dense. It seemed worse in the back than in the front.

“Just then Daniel Lund, employed by the photographers in the front studio, came in and urged the girls to go to the roof. They fled from the studio with Lund and Adelaide Hill, manager of my studio, bringing up the rear.

“At that moment I remembered my lenses. Some of these cost $1,000 each and were not insured. Saying I would join them in a moment. I ran back to the studio. Miss Hill followed me twice and tried to get away, but I wasn’t thinking so much of my own safety as I was of the lenses.” Had Saved Other Lives. (subhead)

“It was then so thick with smoke in the studio that I could not see any-thing. I found the lenses, however, and put them in my pocket. Then, afraid I would not be able to get out of the front, I went to the rear. A man told me to jump to an adjoining roof three stories below. but it was too far. I started to pick up the long wires connected with my electric lights, planning to drop down with the aid of these.Then I felt the smoke overcoming me. “At that moment Lieutenant Fletcher ran into the studio. He grabbed me and told me to get out. Then, seeing a watch on the table, he asked me it it was mine. I said it was. “Take it.” Fletcher said, and I slipped it Into my pocket and he helped me out and up the stairs to the roof. There he fell, overcome by smoke.” … Girls employed by Gallo were incensed at the lack of ladders on the fire-escapes. “We knew nothing about the fire until I Lund ran is from the Curtis Bell studio,” said Miss Hill rang and the fire had been in progress twenty minutes before we knew of it. Mr. Lund saved our lives.”

Peter C. Spence, head of the Fire Prevention Bureau, said last night that the fire-escape that had no ladders probably was a “part wall fire-escape,” by means of which persons could pass from one building to another separated from it by a fire wall. “That fire-escape,” Mr. Spence said, was accepted by the Board of Standards and Appeals and was beyond my Jurisdiction. I did not even go into the building. Mrs. Albert Sterner, wife of the artist it became known yesterday, also was trapped on the ladderless fire-escape. She was being photographed in the Curtis Bell studio by B. M. Pearson when Miss Mary Cullen ran in with the alarm of fire. Mrs. Sterner was led to the Gallo studio, as the elevator, in front had stopped running. She joined the girls on the fire-escape until they discovered there was no ladder. Then she escaped through an adjoining building.

1922-25: On June 6, 1922: a huge wrinkle: King, supposedly an “intimate” friend of Fairchild, files a lawsuit against Charlotte Fairchild, Inc. (1876-1927) a photography studio. King claims she had obtained funds of $8000 from another party (actress Helen Ware) for the benefit of Fairchild in order to purchase the controlling interest of stock (180 shares) from Curtis Bell, at the time, President of Curtis Bell, Inc. who had told Fairchild in early 1921 he wished to sell his studio. With an agreement to sell secured, and Bell mostly untethered from the business, he still grew concerned by late 1921 that Fairchild was not present to run the studio space he still shared as a joint business venture, and on January 11, 1922 he told her to vacate 620 Fifth Ave.

(Editors note: this is a complicated lawsuit with details lacking: consult with the printed court transcript here.)

Bell, in testimony, stated he was living in Bryn Mawr Park, Yonkers, N.Y.. During a trial at New York Superior Court, the photographer said he originally wanted to sell his studio in 1921, first asking $12,500 from Charlotte Fairchild. The price was bargained down to $7500 by a Col. Arthur W. Little, a printer and bookbinder, representing Fairchild’s interest. An agreement was made, and the Bell studio, with 180 of its controlling shares, (actually owned by Bell’s wife Elsie L. Bell) was sold to Alice King for $4000 in cash and a promissory note of $3500. King, who brought the lawsuit, testified Fairchild had asked her to loan her the $ to complete the sale of the Curtis Bell Studio in exchange for her to become business manager of the new concern. King had been a “business getter”, working for Victor George and Moffat’s Studio in Chicago previously, so her background was in the photo studio business-not behind the camera lens.

Fairchild testified Bell had visited her after a telephone call in early 1921: he was offering to sell his studio along with a valuable collection of 20 years of his negatives and his long-term lease that would run another 20 years at the 620 Fifth Ave. location.

The gist: Fairchild, according to Little, was so financially indebted due to other obligations that she could not run her own photo business, let alone a joint partnership with Bell. This is where King stepped in. She ended up bringing court action against Fairchild and Col. Little in Superior Court for not paying back money she said she had paid to acquire the Bell Studio.

On February, 6, 1925, coincidentally only two days after a fire caused damage to Bell’s studio and killed a firefighter responding, a jury trial was held in the New York Supreme Court’s County Court House in Manhattan. Plaintiff Alice King, sought 15k in damages in a court action she brought against defendants Charlotte Fairchild, Inc. (a photographic studio) and Col. Arthur W. Little, a printer and bookbinder, representing Fairchild’s interest. She would lose the case, which was appealed by King but later denied by the court. The courts written conclusion:

This action represents an attempt by the plaintiff to charge the defendants with liabilities they never assumed, for the purchase of a business which the plaintiff operated for her own account and found unprofitable. Neither the business nor any of the insignia of the ownership of the business were ever delivered or tendered to the defendants. The plea that it was impossible to make a tender we have shown to be fallacious.

The evidence almost, if not quite, justified the direction of a verdict in favor of the defendants.

The plaintiff’s requests to charge were improper both in form and in substance and were correctly refused by the trial Court. ‘The exclusion of evidence complained of was both correct as a matter of law and harmless to the plaintiff, as she was permitted to get her position fully before the jury.

‘The verdict was the only possible one on the evidence and should be sustained.

Respectfully submitted,

SAMUEL H. KAUFMAN,

Attorney for Defendants.

1925: After the Bell studio was cleaned up from the fire, a first reference to Curtis Bell, Inc. indicating the studio was now in the control of other photographers: advertisement in the New York Evening Post, 10 October: A Gift for the Bride: It has been our privilege to photograph as brides many of the socially prominent matrons of today. The artistry and quality of our work is of the highest standard as befits this supreme occasion. To broaden the acquaintance with our work we will:

Present the bride with one extra large (11×14”) portrait of herself, absolutely free with an initial order for one dozen of our fine 8” x10” size photographs at regular prices. Offer Good Until November First. Make your appointments now for sittings either at our studios or in your home. CURTIS BELL, INC: “Artists in Photographic Portraiture” 620 Fifth Avenue Tel. Circle 2932-5087

1927: Dies in Yonkers, N.Y. on December 17. New York State Death Index # 71204 via FamilySearch

1929: The Bell studio holds on, but is believed to have gone under by the trauma induced as a result of the October New York Stock Market crash. On Sunday, October 13 in The New York Times: a final published photograph: “Who Will Be a November Bride” gives a Bell studio credit for a portrait of Miss Eleanor Coghlin Gibbons, fiancee of William Radford Coyle.

✻ ✻ ✻ ✻ ✻

Notes:

- Excerpt: Gary D. Saretzky: Elias Goldensky: Wizard of Photography, copyright 1996. This is by far the most important and definitive overview of Goldensky’s life and career. The following Editor’s Introduction from Sadakichi Hartmann’s collection The Valiant Knights of Daguerre gives a good idea of the politics of the new Bell Salon and the the Photo-Secession at this time: “Stieglitz had been planning to organize a governing body for all of the national pictorial groups, which would include the Photo-Secession and encompass ties with The Linked Ring in England. He also envisioned a large international exhibition of pictorial photography to be held in New York in 1905. None of this came about. Instead, a rival group of pictorialists — the Salon Club of America, which had been quietly organized in December, 1903, led by Curtis Bell, a professional photographer only recently arrived in New York— stole a march on the Photo-Secession and announced plans for the first “American Photographic Salon” in New York to be held in December. 1904. The photographic press was filled with the attacks of Bell and his supporters on Stieglitz, whom they charged with trying to dictate the future of pictorial photography.”

- Excerpt”: Sadakichi Hartmann: “The Salon Club and the First American Photographic Salon at New York” in: The American Amateur Photographer, July, 1904, pp. 296-305

- 1875 New York State Census: family tree

- In 1883, the year Curtis might have graduated high school, the Brooklyn City Directory lists his father Thomas Bell’s details: inspector, living at 359 Hoyt St.

- p. 48, entry #240: 1896: A partial record of the descendants of John Tifft, of Portsmouth, Rhode Island, and the nearly complete record of the descendants of John Tifft, of Nassau, New York

- Halftone portrait of Curtis Bell by J.C. Strauss: Editors’ Introduction: The Valiant Knights of Daguerre, Sadakichi Hartmann, edited by Harry W. Lawton & George Knox, University of California Press, 1978, p. 22

- Curtis Bell, Inc. studio credit printed along with portrait of Miss Eleanor Coghlin Gibbons, fiancee of William Radford Coyle, in the Sunday, October 13, 1929 edition of the New York Times.