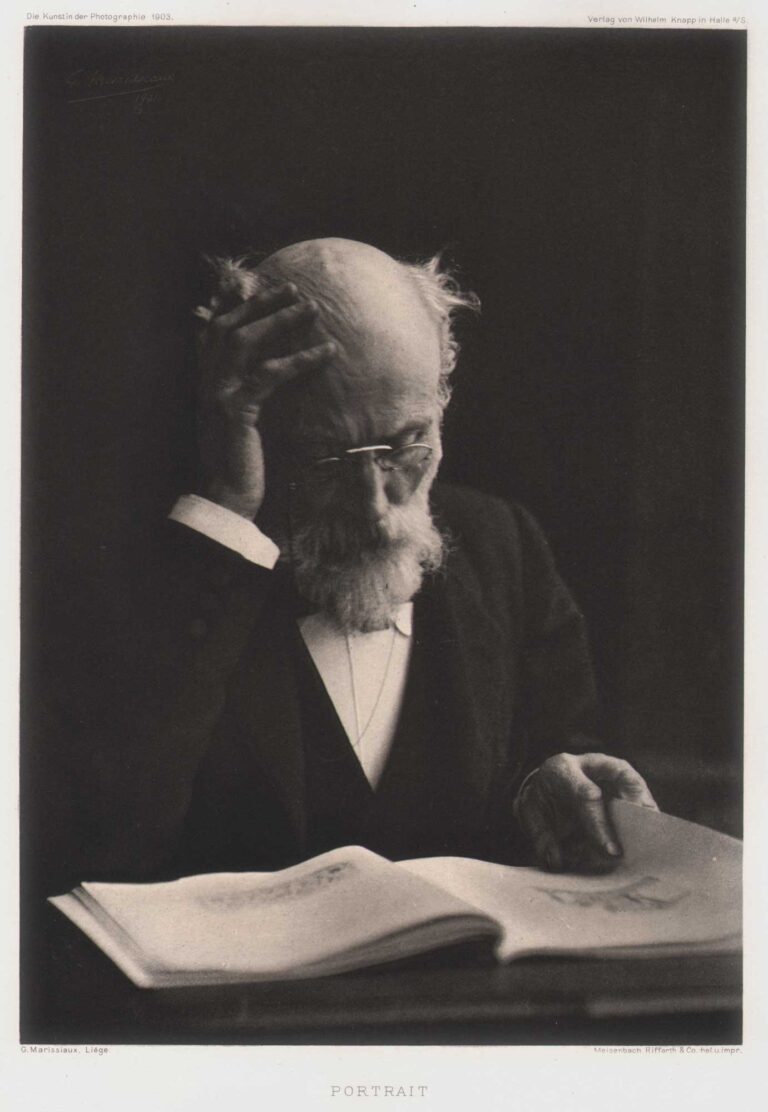

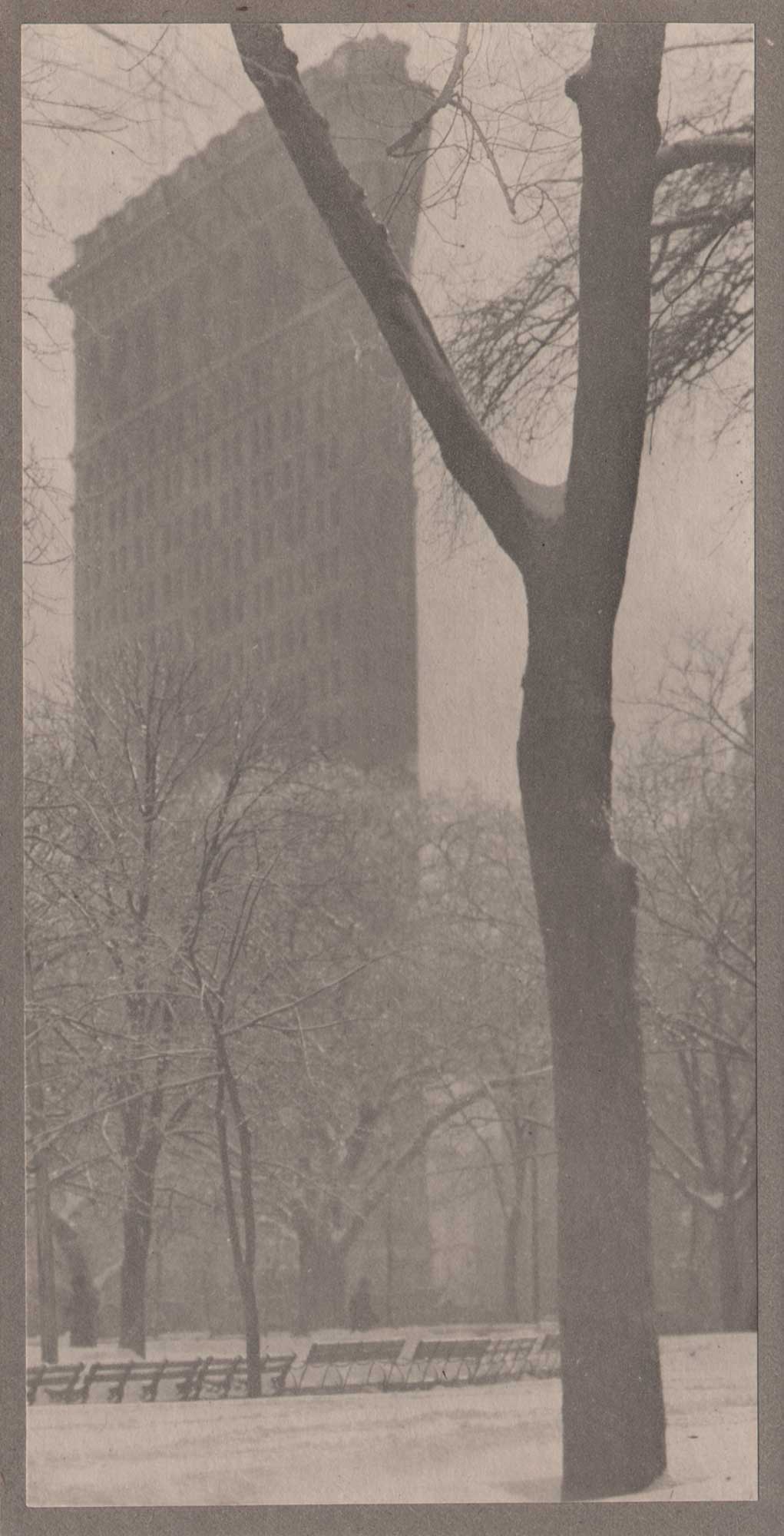

The “Flat-iron”

A wintry view of the Flatiron Building, which opened in 1902 in New York City. The now iconic building can be seen through the trees of Madison Square Park, a lone figure silhouetted in the distance, beyond park benches and tree branches coated in snow.

American art critic and poet Sadakichi Hartmann (1867-1944) wrote the following poem, published within the pages of Camera Work IV, 1903, in which this photogravure appeared.

TO THE “FLAT-IRON.”

ON ROOF and street, on park and pier

The spring-tide sun shines soft and white,

Where the ” Flat-iron, gaunt, austere,

Lifts its huge tiers in limpid light.

From the city’s stir and madd’ning roar

Your monstrous shape soars in massive flight;

And mid the breezes the ocean bore

Your windows flare in the sunset light,

Lonely and lithe, o’er the nocturnal

City’s flickering flame, you proudly tower,

Like some ancient giant monolith,

Girt with the stars and mists that lour.

All else we see fade fast and disappear-

Only your prow-like form looms gaunt, austere,

As in a sea of fog, now veiled, now clear.

Iron structure of the time,

Rich, in showing no pretence,

Fair, in frugalness sublime,

Emblem staunch of common sense,

Well may you smile over Gotham’s vast domain

As dawn greets your pillars with roseate flame,

For future ages will proclaim

Your beauty

Boldly, without shame. S.H. (p.40)

✻ ✻ ✻ ✻ ✻

In the same issue, writing under his pseudonym “Sidney Allen”, Sadakichi Hartmann wrote the following in depth criticism of the Flatiron Building, on pp. 36-40, which opened in 1902:

THE “FLAT-IRON” BUILDING. -AN ESTHETICAL DISSERTATION.

ESTHETICISM AND the “Flat-iron.” Isn’t that a paradox at the very start?

“Surely, you do not mean to tell us that the eyesore at Twenty-third Street and Broadway has anything to do with art?” Some of my readers will incredulously ask. Why not? At all events, it is a building although belonging to no style to be found in handbooks or histories of architecture-which, by its peculiar shape and towering height, attracts the attention of every passerby. True enough, there are sky-scrapers which are still higher, and can boast of five or six tiers more, but never in the history of mankind has a little triangular piece of real estate been utilized in such a roffne manner as in this instance. It is typically American in conception as well as execution. It is a curiosity of modern architecture, solely built for utilitarian purposes, and at the same time a masterpiece of iron-construction. It is a building without a main façade, resembling more than anything else the prow of a giant man-of-war. And we would not be astonished in the least, if the whole triangular block would suddenly begin to move northward through the crowd of pedestrians and traffic of our two leading thoroughfares, which would break like the waves of the ocean on the huge prow-like angle.

A curious creation, no doubt, but can it be called beautiful? That depends largely on what is understood by beautiful. Beauty is a very abstract idea. The painters of the Middle Ages represented the human body in an angular, ascetic way, emaciated and long-drawn; in the Renaissance the human form rounded perceptibly, and in the Rococo it had gained in width what it had formerly possessed in length. All these three styles have been called beautiful, and had their advocates and opponents.

The runs of a quarto by Guido de Arezzo strike despair on modern ears, and a Wagner opera would probably have brought despair to the ear of Guido de Arezzo. We laugh at Allston’s pictures which pleased our grandfathers, and our grandfathers call us crazy for admiring Monet. The most respectable young lady in the time of Louis XV went more decolleté than would any lady without principles and prejudice to-day. The most frivolous girl of the Rococo period would have repudiated even the suspicion of dancing a galop. the Germans ascribe all the changes of taste to the Zeitgeist, i.e., spirit of the time, and history tells us that it has always been so. Every person has his own views of good and bad, on morality, beauty, etc.

And the totality of these views, as represented by a community in a certain period of time, dictates the laws in all matters pertaining to life as well as to art. There are, of course, different tendencies bitterly fighting with each other for supremacy. The artists work out their ideals, the critics argue pro and con, and the public debates and tries to settle matters to its own satisfaction. Suddenly a change in the prevailing taste becomes palpable, rather timidly at first, but steadily growing in strength, and finally old convictions and theories give up the fight and give way to the

new ones. Why should not, in the course of events, the time arrive when the majority without hesitation will pronounce the “Flat-iron” a thing of beauty? I know I will not make many friends with these lines to-day. It is only a small circle which will acknowledge that my claims are justified. But twenty years hence they won’t believe me, when I shall tell them that they would not believe me twenty years ago, for it will have become so matter of fact. The professional duties of the architects have of late become very prosaic and unpretentious, one might say they had acquired a philanthropical tendency. Modern, every-day demands necessitate, first of all, consideration for utility, comfort, and sanitation, and after paying due respect to heating, lighting, drainage, ventilation, fire-proof construction, etc., there remains but file for the show of artistic quality, which amounts on the average to little more than the gathering of fragments of various styles out of excellent handbooks. The problems of popular architecture are mechanical, and the spirit in which they are built economical. This peculiar neglect of beauty in the exterior of our buildings, however, is not killing art, as some wise Philistines remark. On the contrary, it calls forth numerous untried faculties and new combinations, which in turn will help to produce new phases of art.

It has often been queried if there is never to be a new style of architecture, and if the art of building is never to free itself from more or less appropriate revivals. At the first glance, it almost seems, as if all possible curves and lines had been exhausted, and as if there was but little chance for a new, original style with such vastly different structures like the temple at Karnak, the Parthenon, the St. Sophia at Constantinople, the cathedral of Cologne, the pagoda of Nikko, an Italian Renaissance palace, and a Rococo Chateau or Hof. Yet we should not forget, that life has never undergone such a radical change as during the last hundred years. The change has been from top to bottom, in all our ways of expression; not one stone of the old structure has been left upon the other. The whole last century has been one uninterrupted revolution-restless, pitiless, shameless, gnawing into the very intestines of civilized humanity.

Nothing has resisted its devouring influence, nothing, absolutely nothing has remained of the good old times; they have vanished with their customs and manners, their passions, tastes, and aspirations; even love has changed; all, everything is new.

Were the most learned art commissioners to stand on their heads they could not deny or alter the fact. And as life has become totally different, and art, the reflection of life, is following her example, should architecture, the most reliable account the history of mankind has ever found, only make an exception?

I, for my part, do not only believe in the possibility of architectural originality, but am convinced that it will first reveal itself prominently in America. There is something strictly original about our huge palatial hotels, our colossal storage-houses looking at night like medieval castles, the barrack-like appearance of long rows of houses made after one pattern, our towering office-buildings with narrow frontage, and certain business structures made largely of glass and iron. And amidst all these peculiarities of form a new style is quietly but persistently developing.

Thousands work un-consciously toward its perfection, and some day when it has freed itself from a certain heaviness and evolved into a splendid grace it will give as true an expression of our modern civilization as do the temples and statuary of Greece.

I mean the iron-construction which, as if guided by a magic hand, weaves its network over rivers and straight into the air with scientific precision, developing by its very absence of everything unnecessary new laws of beauty which have not yet been explored, which are perhaps not even conscious to their originators. Alas, the beauty of this new style is hidden in the majority of cases and only reveals itself in viaducts, exposition-halls, and railway-stations. If the architects could only be persuaded to abolish all pseudo-ornamentation. Byzantine arches and Renaissance pillars have nothing in common with our age. In the same way as the equipment of the interior is subordinated to modern conveniences, the exterior decoration should be guided by the laws of common sense. Iron, steel, and aluminum structures demand other embellishments than the conventional friezes, capitols, and arches of stone and timber architecture. One can readily understand that innovations in

ornamentation are hardly possible before the new style itself has reached maturity. But nothing is gained by slavish copyism. It only distorts the truths unconsciously arrived at by scientific calculations. Our polyglot style is largely due to the lack of original ornament. Who is going to invent it? The column entwined by the Acanthus, the basis of much that is beautiful in Greek ornament, can not be so easily replaced. And yet it Seems strange, that we should have never been able to evolve a single strictly American pattern out of the manifold products of our country, or its historical associations. The tomahawk or the Indian corn would surely lend itself to a decorative treatment. It is barely possible, however, that the new structural tendency will call forth an entirely novel style of decoration, much more bulky than hitherto, with a neglect of detail, as is seen only from distances, and impressive rather in its effects of masses than those of form. Perhaps the use of color will prove a new and immediate stimulant to exterior architecture. The absence of chiaroscurial efects peculiar to these buildings points in that direction.

Mr. Charles Barnard, author of the “County Fair,” a civil engineer by profession, remarked to me one day: “There is really no ornamentation necessary at all, but the people won’t stand it; they think a building would tumble down, if the lower stories were not executed in pseudo arches and imitations of massive stone embankments.” This is the gist of the whole problem.

The architects do not yet dare to obey the laws of common sense, and to employ only such decorations which serve some practical purpose, or which really enhance the building, having a raison dêtre for their existence, and not merely being fastened to the walls as it is now invariably the case. A building without any exterior decoration may look prosaic and monotonous to us, and yet I must confess that the rear view of sky-scrapers has always appealed to me more than the façade, whose ornamentation, particularly of the upper tiers, produces only a general effect. In the rear view the laws of proportion, the comparative relations of large flat surfaces, broken by rows of windows, create the esthetical impression. “The simpler, the better” has always been the motto of art. The Doric style is grander than the ornate Corinthian. Why should not a simple truss, as used in the construction of bridges and roofs, be considered as beautiful as Hogarth’s “curve of beauty”? Surely the boundary lines of girders, the trestlework of viaducts, and all the skeleton constructions with their manifold but invariably scientific methods of connections (in simple buildings like the tower on lower Broadway, the Western Union Building, the Navarro Flats, etc.) contain a variety of geometrical forms similar to those which have created the arches and vaultings of the pointed style.

And why can not the Eiffel Tower and the Brooklyn Bridge be compared to the architectural masterpieces of any age or clime? They show a beauty of lines and curves, simple as in the pyramids, bold as in the cathedral spires of flamboyant churches, and far-sweeping, as if to embrace the entire universe, a quality which no other style has ever approached.

Have you ever sailed up New York Harbor early in the morning? As your steamer creeps along the shore, and you first see the city tower through the mist, is it not as if you had come at last to the castles in the air you built and lost so many years ago? Do you not imagine you already see the hanging-gardens, the fountains, the men and women with strange garments and strange eyes? But, after all, it is not the materialization of a dream, but the idealization of a fact that you find.

Beauty in America is no longer an instinct, but a realization mirrored in the entire country. And it is from the bridge, that hammock swung between the pillars of life, that New York seems to become intimate to you. The bridge gives back the thrill and swing to thought and step that nature gives in youth. Who can delineate in words the monstrous cobweb of wire, that clings to the turrets, rose-colored in the setting sun, or the steel lines Sinking, the shores, that hover. like the wings of a dragon fly above of The huge office-buildings of lower New York make one think of the vision of some modern Cathay caught up in the air, or become in one’s imagination the strongholds of strange genii whose fevered breath pants out in gusts of steam. And as the night descends, catching a last glimpse of the bridge glinting like a fairy tiara above the waters of the East River, you feel that the City of the Sea has put on her diamonds -and then you notice the words “Uneeda Cracker.”

As yet everything is saturated with the pernicious habit of industry, yelling and writhing before the juggernaut-car of commerce. In France things are shod with velvet, but on Broadway they are not. It would make a quaint hell for some musicians who delight in much brass and tympani. How it stings one-the exuberant, violent strength of the place, sentient with the almost forceful vitality of youth, adolescent in its tentative desire for beauty, it makes one’s blood answer at once its imperious demand for enthusiasm.

It will not always be thus. We, also, will lose our primitive strength; but until that time when men will “dream in crystal caves and fashion strange secrets that murmur the music of all living things,” there is an infinitude of art and beauty in all this mad, useless materiality which, if artists, blinded by achievement of former ages can not see it, will at least give rise to a new style of architecture, rising boldly and nonchalantly from the ruins of the past.

SIDNEY ALLAN.

Hartmann was also an artist. See his painting The Wreck in this archive.