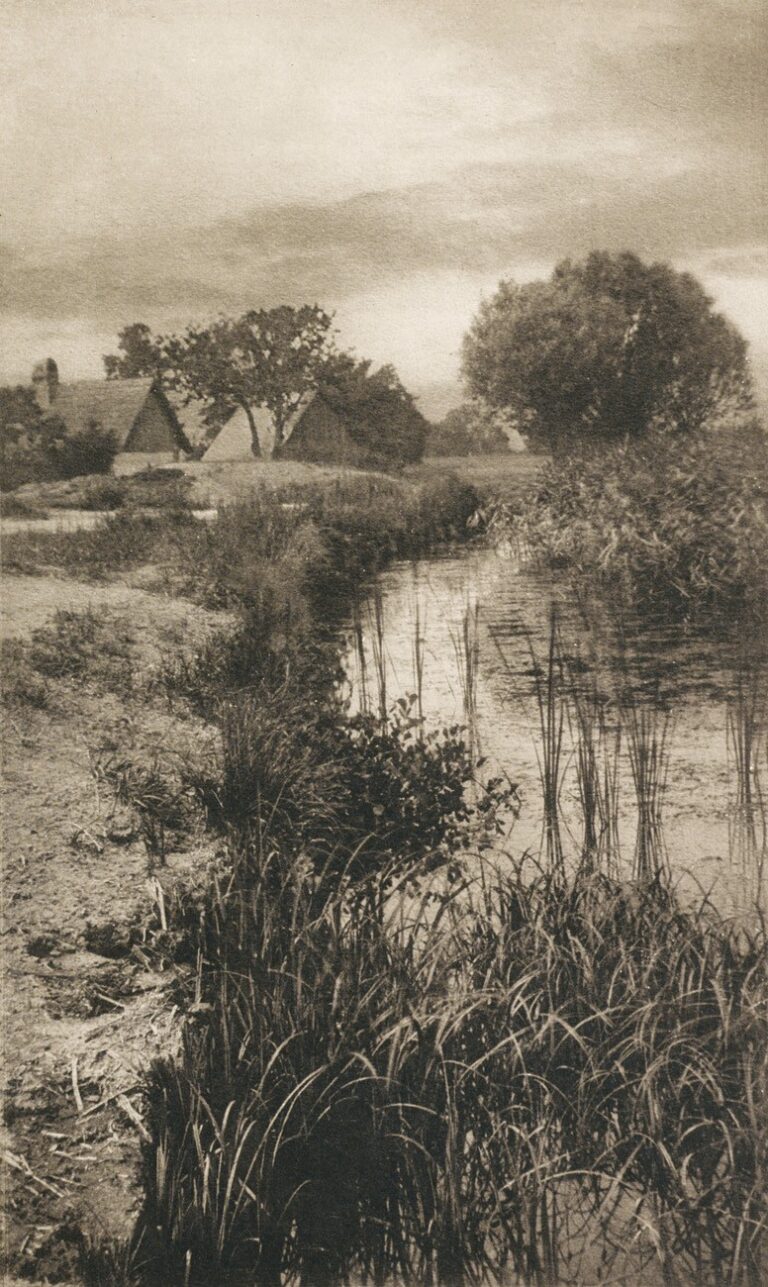

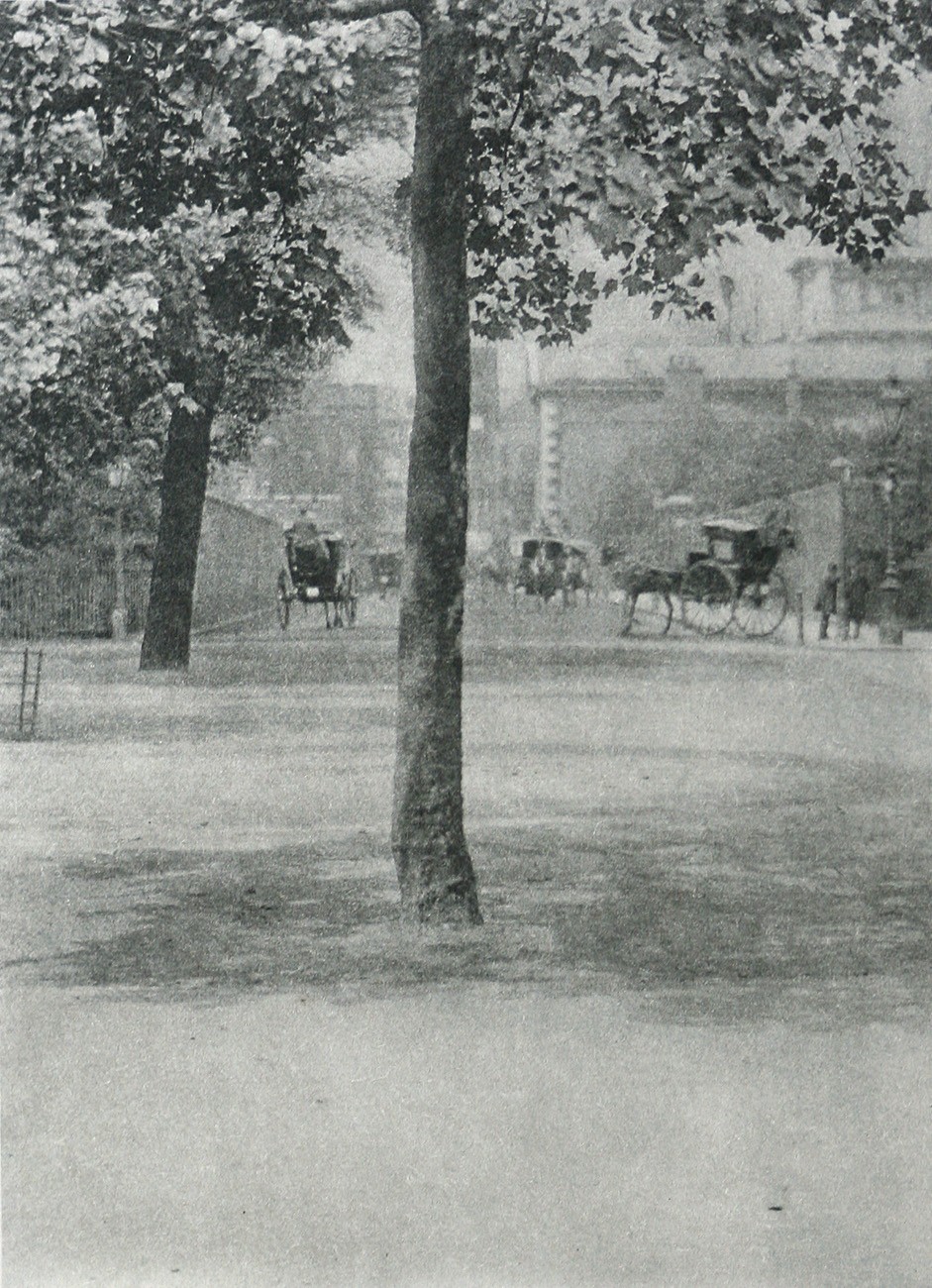

The Mall

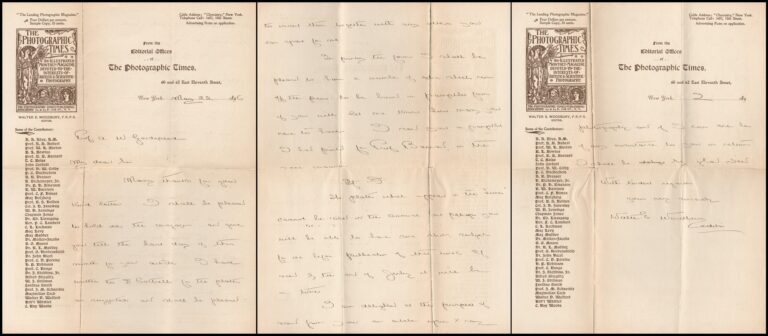

When English photographer Eustace Calland (1865-1959) exhibited his photograph titled The Mall (also known as Pall Mall) at the 1896 Photographic Salon, a small uproar ensued because Calland had framed his photograph with a tree directly in the center of the frame. The breaking of compositional rules was fairly new at the time, yet in complete sympathy with the spirit of Pictorialism. Writing in Photograms of 97, the editor quotes one of Calland’s fellow Linked Ring brothers-Alfred Horsley Hinton, who recounts an exchange based on Calland’s photograph being included in Walter Colls portfolio published later that year:

“Side by side with the tendency against which a protest is thus uttered there has been a healthy growth of sceptical enquiry, which shews that even those who make no pretensions to high-art knowledge are becoming deeply interested in the pictorial aims of others. A curious example of this was given in The Amateur Photographer of July 9, 1897, and arose from a conversation between the editor of that journal and a few members of the Liverpool Amateur Photographic Association. It may best be recorded in Mr. Hinton’s own words. He wrote :— “Mr. John Bushby had persuaded the Council to purchase Mr. Walter Colls’ portfolio of reproductions of Salon pictures, but had been reprimanded subsequently because all the pictures therein contained did not come up to the Lange standard, and there was not included a representation of a Dalmatian dog. But one picture had troubled them more than the rest, and I was to be asked to give an explanation of its being first of all accepted and hung, and, secondly, selected for reproduction by Mr. Colls. I felt uncomfortable, because I remembered one or two of the collection I should have found it difficult to defend; moreover, it might prove to be my own picture, Requiem.

Judge of my surprise, then, when one of the hospitable ring handed me the reproduction of Mr. Calland’s Pall Mall and with a look of anticipated triumph, said, “There, sir; what on earth is there in that to warrant its being selected as a typical picture!” I think my reply was longer than I need give space to, here, but it was to the effect that I was not prepared to analyse the picture off-hand, but I was sufficiently pleased with it that I should be very proud had I been its author.

“But,” said another, “where’s the composition? Can you tolerate a tree trunk nearly in the middle, cutting the picture in halves?” So I took occasion to remark that, important as composition might be, there were even greater qualities to cultivate than composition, and it was a fine thing for a man to have produced a picture with such good qualities that it commanded wide approval in spite of its violation of conventional rules and prescriptions. But there was more in the general look of disappointment which pervaded the group around me than appeared, for I learnt that only a week or two previously Mr. J. A. Sinclair had visited the Association and had had the same question submitted to him, and, oddly enough, he had given an almost identical reply. Said he, “I should be very glad to have produced that picture myself,” or words to that effect.

Much as I admire Mr. Sinclair’s own exquisite work, I should imagine there are some essential points connected with art photography upon which we should be at variance, hence I was interested to find myself in agreement with him on this matter, and as pleased as I believe my interrogators were disappointed.

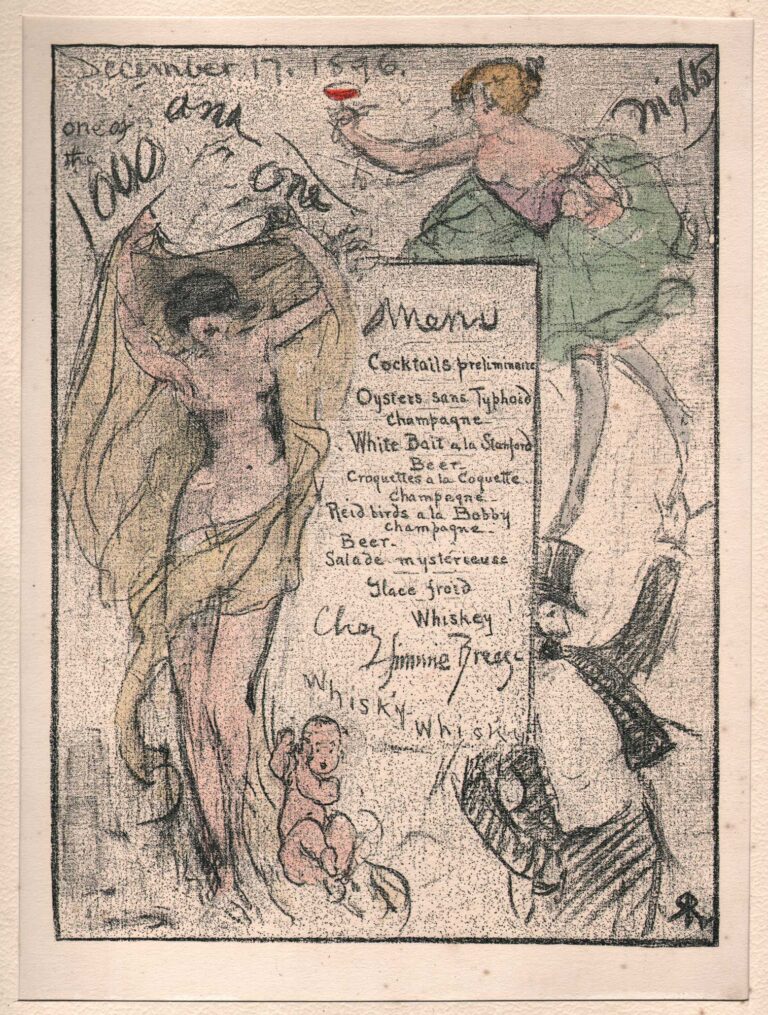

As a pendant to the story it may be added that Llewellyn Morgan, one of the members of the Liverpool Association, saw fit to perpetrate a pictorial parody upon Mr. Calland’s picture; and this parody, a very smart piece of work, is here reproduced, through the courtesy of The Amateur Photographer.

But to return from the joke to the real question. It is one which has been asked, with an honest desire for knowledge, by many photographers beside those of the Liverpool Association, and about many pictures beside the very fine Pall Mall of Eustace Calland. A very similar question was asked at the first exhibition of the Salon, when a certain picture was pointed out as being the finest thing in the room. One of the leaders of the Linked Ring directed the attention of a press-man to the picture, and the reporter at once asked “What is its special point or beauty?” The question was a poser, for the “link “could only reply that it “strongly appealed to one,” or words to that effect. The press-man put the same question to three other “links,” each of whom confessed his inability to say wherein lay the charm of the picture, though maintaining that it was, undoubtedly, one of the very finest works.

This sort of difficulty very often occurs, and is one of the principal stumbling-blocks in the way of the teaching of “art”; for the highest things in art, as in religion, must be felt rather than understood. It is easy to make a series of rules which must rarely be transgressed, and it is easy to point out definite faults : but it is extremely difficult to explain those cases (and in the master’s hand they are many) in which the violation of a rule may add a distinct charm. And it is even more difficult to define those qualities which often render a work admirable in spite of obvious faults. Individuality and obvious intention- even though the intention be not fully realised —are immensely better than mere adherence to rules. Mere mediocrity and slavish adherence to rules have no chance of success nowadays.” (1.)

1. Extract: “Tendencies”: in: PhotoGrams of 97: The Best Photographic Work of the Year Reproduced and Described: Dawbarn & Ward: London: 1897: pp. 7-10

Original copy for this entry posted to Facebook on September 4, 2011:

Talk about controversy, or silliness. When English photographer Eustace Calland exhibited his photograph “The Mall” at the 1896 London Photographic Salon, all hell broke loose: “There, sir; what on earth is there in that to warrant its being selected as a typical picture!” Curious?