Winter in Shakespear’s Country

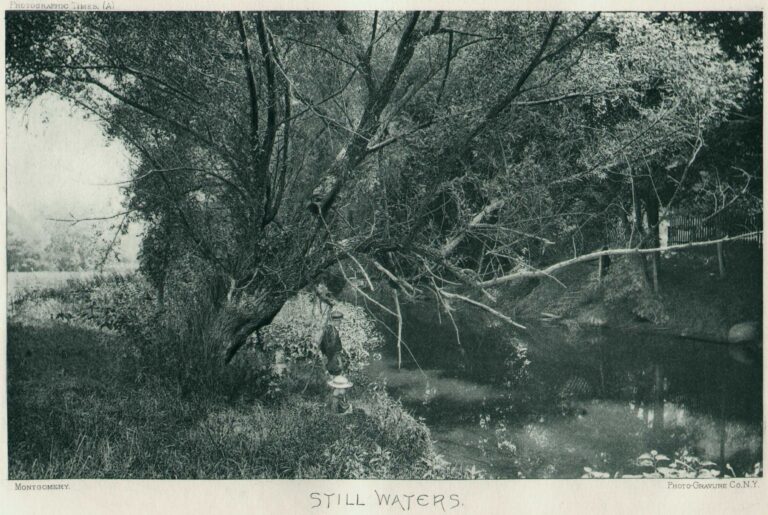

Dr. James Leon Williams, 1852-1932, a pioneering American prosthodontist with the rather unusual historical distinction of having discovered dental plaque, was also an amateur photographer working in the Naturalistic school. At the time this photograph was taken in the early part of 1889, Williams is believed to have been practicing dentistry in London and taking studies around England that would eventually be included as exquisite plate gravures in the 1891 volume The Homes and Haunts of Shakespeare. In his lengthy remarks on this plate spanning three pages titled Christmas-Tide In Shakespeare’s Country published in the Photographic Times of December 20, 1889, Williams chronicles the efforts it took him to make this photograph, with the distinct possibility in my own mind he may have included himself as the lone figure-Shakespeare’s stand-in so to speak- standing next to the fence at the center of the frame. Loaded down with camera equipment, his passage by train from central London to Stratford-on-Avon, a nearly 100-mile-journey, was done with one purpose: to capture the magical yet fleeting effects hoar frost would have on the foliage and landscape surrounding Shakespeare’s native soil:

It came about in this way: I went up to London the last of October, having arranged with a friend in Stratford to telegraph me should there come a heavy fall of snow. I had hoped that this might happen some time during the holidays. I had it all most delightfully arranged in my mind. I should get a telegram some morning about Christmas time announcing the arrival of the long-looked-for snow storm. I should invite one or two congenial friends to run down to Stratford with me, where we should arrive early in the afternoon, go at once to the “Red Horse Inn,” and order a Christmas dinner, being careful, not to omit English plum pudding and some rare old port, which mine host keeps for such occasions, to be served in the cosy little Washington Irving Room. Then we should go for a ramble along down the river, across the white fields and over to the “Wier Brake.” We should come home with an armful of holly to garnish our table, and appetites to do complete justice to the repast sure to be spread for us. I had left the rest of the picture to fill itself out as it naturally would under the circumstances, having learned by repeated experiences that there is quite sufficient healthy sentiment to be extracted from English roast beef and home-brewed ale to furnish the necessary material for such an occasion.

Christmas came, and New Year’s, but never the expected telegram. London had been enshrouded in one of its midnight fogs for several days, when one afternoon it cleared up a little and I noticed as I walked along down the Bayswater Road past Hyde Park that a beautiful hoar frost was forming on the trees. An hour later the branches were quite heavy with it, and the thought came to me that if the frost deposit continued all night the effect in the morning, in the country, would be exquisitely beautiful. Would it extend as far as Stratford? I would chance it. I knew that I must be there quite early in the morning to see it at its best, for two or three hours of sunlight would end it all. A train would leave Euston at six o’clock in the morning. But Euston was two miles away, and there would be no Metropolitan trains or buses running at that hour, and I could not walk that distance and carry my camera and sufficient wraps to keep me from freezing during a four hours’ ride in the English refrigerator cars. I went out to a cab-stand and on the strength of a half-crown deposit secured the faithful promise of a Jehu to be at the door at 5 o’clock in the morning. A hasty breakfast, and at the last minute there is the rumble of wheels and the cab lights shine through the darkness from the gate. It is too dark to discover by sight if the frost still remains on the trees, but I take hold of some shrubs in the garden and bring away a handful of the frozen crystals. An hour later the train draws out from the station. As I have the entire compartment to myself, I wrap my shawls and rugs about me, stretch out on the seat, and am soon sound asleep. We are more than half way to Stratford-on-Avon when I awake, it is past 8 o’clock and the sun is shining in through the car windows. With what eager expectancy I scratch away the frost from the glass and peer out. Never shall I forget my first glimpse of the fairy-land which met my gaze. The scene was almost blinding in its dazzling brilliancy. Every blade of grass, the stem of every weed; the branches of the trees were centres from which projected the most exquisitely beautiful crystals, and every crystal was a prism in which the rays of sunlight were resolved into their primary colors. The effect was wholly different from anything I had ever before witnessed. I remember the delicate, feathery crystals had converted the telegraph wires into glittering ropes more than two inches in diameter.

Even now, after the lapse of many months when the first overwhelming effects of that wondrous vision have long since passed away, as I go back in memory to the scenes of that morning it seems to me that words are utterly powerless to convey any adequate conception of the effects that I saw. It was one of the sights before which the speaking mechanism of the mind is hushed into that silence of awe which is the tribute we render to the Infinite during some few of the rare moments of life. For an hour or more I watched from the car window this changing panorama of fairy land. The forest views seemed the most beautiful where the shining whiteness was relieved by a single touch of color—the green of the holly-leaves. There was something very singular and striking about this effect. All of the other evergreens were everywhere concealed; even the surface of the ivy leaves was completely covered. But the dark, glossy green of the holly was untouched save a delicate fringe of crystals which formed a framework about each individual leaf. Of course there was a bald scientific reason for this beautiful phenomenon, but at such a time one prefers to give fancy a free rein.

I reached Stratford shortly after 10 o’clock and during the next hour secured four photographs, which, while they but very poorly reproduce the wondrously beautiful effects as I saw them, are yet priceless to me for what they suggest. The one accompanying this poorly drawn pen picture was taken from the hillside above the “Wier Brake,” a favorite walk along the river bank about a half mile below Stratford. It is one of the few places about Shakespeare’s home which has remained almost unchanged from the poet’s time.

The country people have a legend that it was his favorite walk and that the forest scenery of “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” was drawn from this locality. On that glorious morning it certainly was a scene worthy of the great Master’s pen. The view looks toward Stratford and the spire of Holy Trinity Church which rises above the poet’s grave is dimly seen through the crystalline vista of the branches of the rugged old English oak in the foreground.

J. L. Williams. (pp. 624-625)

foxing and age-toning to plate

A note on the word Shakespear in the title of this work, considered the modern way to spell his name at the time of publication:

The spelling of William Shakespeare’s name has varied over time. It was not consistently spelled any single way during his lifetime, in manuscript or in printed form. After his death the name was spelled variously by editors of his work and the spelling was not fixed until well into the 20th century. (1.)

1. excerpt: Spelling of Shakespeare’s name: from: Wikipedia: accessed: October, 2012