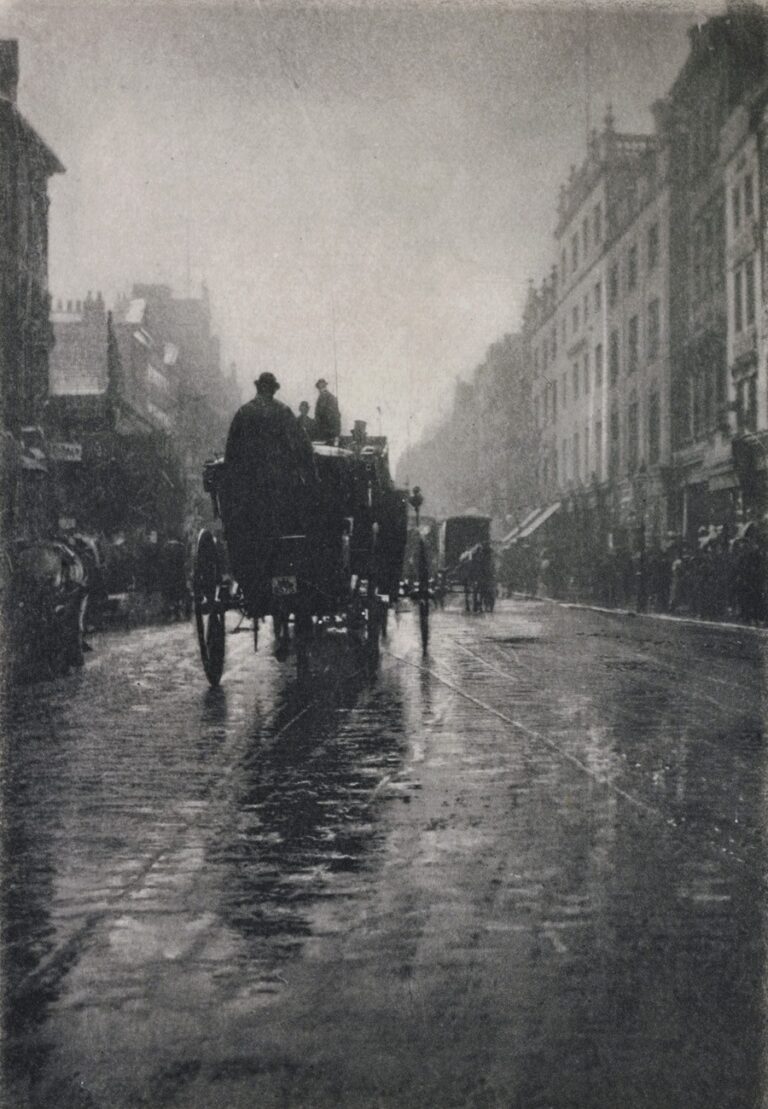

New York by Night

At the same time Alfred Stieglitz was experimenting with night photography on the streets of New York City in late 1896 and early 1897, (see his: The Glow of Night—New York; Reflections Night—New York and An Icy Night) New York Camera Club member William Fraser was also working in the dark. Following published working methods as practiced by photographer Paul Martin in England, Fraser made this winter scene using a tripod-mounted camera with the exposure illuminated by electric street lamps in Manhattan. (1.) In addition to this plate serving as the frontis photogravure for the April issue of The Photographic Times; Fraser also wrote an article for the issue titled Night Photography. (see pp. 161-163)

Fraser’s night work brought medals and accolades from around the world. The editors of the journal thought enough of his practices in this novel dark art to include them as part of the listing for Night Photography in their ENCYCLOPÆDIC DICTIONARY OF PHOTOGRAPHY—published in the collected 1897 volume following the December issue. The original entry in its entirety:

NIGHT PHOTOGRAPHY.—Very successful photographs have been made at night time using the illumination from the electric lights. Figs. 296 and 297 are examples made by Mr. W. A. Fraser. This gentleman thus describes his method:

“The first requisite is a strong weather-proof box camera. The one I use for this work is an old style Scovill detective, long ago laid on the shelf, but it struck me when thinking the matter over, that its strength and solidity, made it a very suitable instrument for this purpose, and much work done with it during the past winter has confirmed me in this opinion.

I carry a light folding tripod which can be quickly and easily attached to or detached from the camera, as working in the dark with hands numbed from cold and wet, the simplest operation becomes a task, and the more simple the apparatus, the better the chance of success.

The lens I use is a Ross rapid symmetrical worked at full opening f8. Mr. Martin advises the use of a slow orthochromatic plate, but considering the good quality of the fast plates as now made, and the great advantage gained by reducing the time of exposure, an advantage which one will appreciate after a single trial, I very much prefer them, and results do not, in my opinion, suffer in the least from their use. As halation must be guarded against, I adopted for this work the Seed non-halation plate, and back them as a further precaution.

Working on Mr. Martin’s lines I at first included in the exposure a minute or two of the last departing daylight, if it might so be called, but my negatives approached too nearly daylight results, and I have since waited until night has really fallen before making the exposure. Having chosen the view and set up the camera, if the only lights included are gas lamps the exposure with this lens and plate should be from eight to ten minutes, depending somewhat upon the distance to the nearest light, while, if any near electric lights are included, from two and one-half to three and one-half minutes will suffice.

When I speak of electric lights, I refer to those enclosed in opal shades, such as are used on Fifth and upper Madison Avenue in our city. Unprotected lights or those enclosed in plain glass shades I have never attempted, and doubt very much if they can be successfully photographed.My moonlight pictures were taken between 10 and 11 o’clock, P. M., with moon almost full, and ten minutes exposure. During the exposure, a watch must be kept that no vehicle carrying lights crosses the field of view. My practice is to stand beside the camera, keeping one hand firmly on it, if it is blowing hard, several exposures I found were ruined through movement of the camera caused by the strong wind, then when a cab or other vehicle carrying a light enters the field of view, I, with the other hand, cover the lens until it has passed. Moving objects not bearing lights make no impression on the plate.

In the development I aim at softness, and use a rather weak metol developer, two ounces stock solution diluted with water to four ounces, and with very little, say two drachms, alkali, no bromide.The amount of detail picked up by the lens when using this plate, has been a constant source of wonder to me; in every case, very much more than my eye could see was disclosed when the plate had been developed and fixed. I prefer a stormy night for this work, either snow or rain, as the artistic effect is unquestionably much greater on these occasions.” (2.)

Original copy for this entry posted to Facebook on June 3, 2012:

A rare night photograph reproduced in hand-pulled gravure included in the recent addition to the site of The Photographic Times journal for 1897 lead me to discover an article on the preferred working methods for this novel (for the time) photographic discipline. New York Camera Club member William Fraser, along with fellow club member Alfred Stieglitz and Paul Martin in England were responsible for showing the potential of night photography. Fraser was considered the go-to person in this field, enough that the entry for Night Photography in the Times supplement the ENCYCLOPÆDIC DICTIONARY OF PHOTOGRAPHY quoted Fraser with this gem: “I prefer a stormy night for this work, either snow or rain, as the artistic effect is unquestionably much greater on these occasions.”

1. the outline of the glass lamp housing at center has been etched into the plate using a burin in order for there to be some delineation

2. Night Photography:in: THE ENCYCLOPÆDIC DICTIONARY OF PHOTOGRAPHY :from: The Photographic Times: New York: follows December, 1897 issue: pp. 300-301