Group Photo: One of the 1001 Nights Costume Party: December 17, 1896

A flash-light photograph of the assembled company was taken at supper.

This group photograph features some of the 70 costume party celebrants who attended the “One of the 1001 Nights” party held at photographer James Breese’s Carbon Studio and townhouse in New York City on December 17, 1896. The following in-depth newspaper article, in which 70 members of New York’s Gilded Age Society and those of “The Four Hundred” took part, (with the highlight being a woman’s flaming dress doused by champagne 1.) was published on Sunday, December 27, 1896- ten days after the party. It appeared in William Randolph Hearst’s Sunday American Magazine: Popular Periodical of the New York Journal:

WHAT CAN NEW YORK SOCIETY BE COMING TO?

The True and Instructive Story of the Gathering in Artist Breese’s Studio Which Ended in a Fire Extinguished by Champagne.

A Society Swell Served Beer and Pretty Nearly Everybody Smoked Cigarettes.

The hard-working ancestors of New York’s society folk would have held up their hands in holy horror if any one had whispered to them the story of antics such in their descendants participated in last week. New York’s four hundred has ceased to be conservative. It seems to be striving to become the wildest set in the world. It will be a long time before the town stops discussing the fact that a captain of police felt justified in leading his officers into Sherry’s ultra fashionable banquetting halls and threatening to raid a bachelor supper given there by Clinton Burton Seeley, on the ground that is was to be accompanied by immoral dances.

There are many stories about the affair. The guests say that it was wholly moral, but admit that it was lively-very lively. The police captain declares that only his interference prevented it from becoming a very wicked episode. And this strange thing was preceded by another. It occurred at Mr. James L. Breese’s studio in West Sixteenth street. Mr. Breese gave a fancy dress supper there the other night, to which only seventy people were invited, and the seventy were carefully chosen from New York’s social elect. Only that same social elect knows how many similar merrymakings have transpired at Mr. Breese’s studio and other exclusive places. Only that same social elect would have known anything at all about this entertainment if it had not come near to having a tragic ending. Society gasped at the undesired publicity, and ordinary humanity gasped at the marvel of revelation when the newspaper’s printed it.

Mrs. George B. de Forest, the wife of one of the trustees of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and a member of one of the city’s oldest and most aristocratic families, narrowly escaped being burned to death as a result of the exuberant liveliness of the entertainment. One of the men present had been amusing himself by throwing matches in the air. These, of course, eventually landed on the floor. Mrs. de Forest stepped on one. It ignited and instantly her gauzy dress was in a blaze. An eye witness, in describing the episode, said: “There was no water handy, so some one put the fire out with champagne.”

Alas! Alack-a-day! What would the staid and solemn progenitors of New York’s four hundred have said about a supper where it was necessary to save the life of a prominent society woman (jeopardized through nonsense) by deluging her with champagne, because “there was no water handy”?

Other details of that stirring night in Mr. Breese’s studio have been lacking until now. They are given below, and they offer to the student an instructive picture of the way in which the wealth and fashion of Gotham-the richest wealth and the most fashionable fashion-amuse themselves.

The invitations were issued three weeks ago. They asked the chosen seventy to be present, in fancy dress, at a revel to begin at midnight, December 17, at Mr. Breese’s studio, No. 5 West Sixteenth street.

The invitations were sent mainly to young married people, although several bachelors and two or three unmarried women were invited. For more than a week society people wondered what surprise Artist Breese had in store for them. They knew a surprise was coming. Surprises are Mr. Breese’s specialty. At the Knickerbocker, the Racquet and the Calumet clubs, where young New York society men compose the membership, there was eager expectation about the forthcoming entertainment.

The fancy dress affair at the studio of Jimmy Breese was the most informal entertainment at which New York society people have ever assisted, and it was unconventional to a degree never before attained. Clubman Samuel Welch Perkins and his brother, George L. Perkins, dressed as bartenders, served steins of beer to such picturesque characters as Reginald de Koven, dressed as an Anarchist, and to Mr. J.J. Van Alen, who appeared as a Dutch burgher, while women well known in society sat around at —tables drinking champagne and beer and smoking cigarettes.

The bar had been fitted up at the end of the long studio. Several kegs of beer had been tapped. There was no provision for mixed drinks, and the back bar was formed of the maroon-colored canton flannel with which the walls of the studio are draped. Beautiful Turkish lanterns, within which were incandescent electric lights, were strung along the ceiling.

In the “Turkish corner” were large divans with an abundance of soft and downy pillow. The rugs and carpets had been taken up from the floor of the studio, which was waxed for dancing. A number of small tables were set about the room, and each of these bore boxes of little Turkish cigarettes for the ladies. Larger cigarettes were provided for the men. Beautiful portraits of society women done by a secret process of Mr. Breese’s were hung upon the walls.

Clubman Sam Perkins, the head bartender, was promptly on hand at 11 o’clock. Nobody had arrived up to that time. He donned his bartender’s apron, rolled up his sleeves and took his place behind the bar, much to the astonishment of Sherry’s waiters, who were amazed to see a well-known New York society man thus prepare to serve drinks. By 11:30 the guests began to arrive, and from then on until 1 there was a steady procession of carriages at the door.

The guests began to smoke almost as soon as they arrived. The men were the first to light cigarettes, which they puffed while quaffing steins of beer which Clubman Perkins served. Meanwhile Sherry’s waiters were busy opening bottles of champagne.

This was served in profusion to all who wished it before the supper.

Here and there some of the fashionable women began to calmly light cigarettes and inhale the delicate smoke like experts. This occasioned no remark, for the women of the Four Hundred have lately taken to smoking cigarettes, which are now served to them at every fashionable dinner as a matter of course.

Mrs. George B. de Forest, one of the guests, was dressed in an Oriental costume. Her gown was light and gauzy and a handsome yashmak was wound about her head.

She was in a group of ladies including Mrs. Hermann Oelrichs, Mrs. Pierre Lorillard Ronalds, Miss Virginia Fair and Mrs. Reginald De Koven, all of whom were especially attired for this novel entertainment.

Suddenly the gauzy dress of Mrs. de Forest caught fire as described. The flames leaped rapidly from one fold to another of her dress. Screams were plentiful, and the ladies who had been assembled in a group chatting but a moment before quickly scattered.

There were cries for water. But in this jolly assemblage no water was to be found, except a little melted ice from the pails holding the champagne bottles. Three was a good deal more champagne than water at hand.

A champagne bottle was seized and its neck knocked off against the wall. Then the contents of the bottle were poured over the flaming dress. Another and another bottle of champagne was similarly broken.

There was enough of the wine at hand to put out a considerable fire, and the amateur bartenders stood ready to pour out the contents of their kegs of beer if necessary. But the flames that threatened the dress of Mrs. de Forest were extinguished with a couple of quarts of wine. Sobbing and trembling, with her charred skirts clinging to her, Mrs. de Forest was led to Mrs. Breese’s apartments to recover her composure. The other guests were soon quieted, and society life bean again.

There was no regular programme for the evening’s entertainment. Programmes are conventional and this was understood to be a most unconventional assemblage.

Mr. Breese, who prides himself on his resemblance to Henry the Eighth, but who was dressed for this occasion in the garb of a Turkish pasha, announced that a cake walk would take place. Mrs. Clinch Smith, whose husband was a nephew of the late Mrs. A.T. Stewart, was the principal figure in this, assisted by Mr. Cadwalader, whom everybody referred to as “the man from Philadelphia.”

Mrs. Clinch Smith, whom nobody recognized in the black and smiling Dinah who danced out upon the floor, was admirably dressed for the part. Her face was as black as coal, and she wore a tousled wig. Her gown consisted of a salmon-colored calico dress with a loud plaid patter, and she wore an enormous hat. Mr. Cadwalader, with loose, loud-checked trousers, big shoes and a flaring red necktie, took the part of Sambo. At the same time a group of genuine negro banjo players came into the room and took their seats.

Then Mrs. Clinch smith and Mr. Cadwalader executed what was described as “An old plantation breakdown.” This was followed by negro songs, including “I Want You, Ma Honey,” “Push Dem Clouds Away,” and “Way Down Upon the Suwanee River.” These songs were admirably rendered in rich, melodious voices apparently well trained in the negro dialect, and they were vigorously encored.

Nothing of this kind had ever before been seen at any fashionable New York society entertainment, and the guests were highly pleased. There was much speculation as to who the black lady might be, and the guesses as to her identity covered a wide range of fashionable women.

Mrs. Clinch Smith subsequently appeared in a regular ball dress after washing off the burnt cork and removing her wig. She was one of the prettiest women in the room, and everybody congratulated her upon the success she had made in her negro part. Mr. Cadwalader afterward appeared in the dress of Li Hung Chang, wearing a long yellow riding jacket, and having his Chinese hat ornamented with three-eyed peacock feathers.

Then followed songs on the part of the male members of the company, who volunteered, as Salvationist Cooper Hewitt remarked, “from the ranks.” A regular orchestra provided dance music. The little French cafe, tables were removed to the side of the room, and “Take your partners for the lancers” was shouted by the master of ceremonies.

Supper was served at 2 o’clock by Sherry. It consisted of soup, bird, ices and glace fruits. Champagne was opened copiously and cigarettes were passed around among the ladies.

A flash-light photograph of the assembled company was taken at supper. Several times throughout the evening groups of the aristocratic revellers were artistically arranged and flash-light pictures taken. Every guest was given a souvenir in the form of a clever reproduction of a water-color sketch by Metcalf.

After the supper the fun began in earnest, and everybody danced. There were a few waltzes, but the square dances were more popular. These gave opportunity for effective groupings of the picturesque costumes upon the floor. It was 5 o’clock before the revellers began to go away from this novel entertainment, and it was an hour later before the last of the guests bid their host and hostess good-by.

Among the guests were Mr. and Mrs. Hermann Oelrichs, Mr. Oelrichs was dressed as a New Amsterdam burgher. He wore knee breeches, a broad-brimmed hat and a long coat, held in place by a buckled belt. Big buckles were on his shoes and his collar and cuffs were large and handsome.

Mrs. Oelrichs resembled Rembrandt’s “Burgomasters Wife,” as shown in the picture in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Her costume was of brown linsey-woolsey, well set off by an enormous lace ruff at the neck. Mrs. Oelrichs is one of the most beautiful women in New York society. The quaint, plain little gown which she wore exactly suited her peculiar style of beauty and she was pronounced one of the successes of the evening.

Mr. and Mrs. Carroll Beckwith were among those present. Mrs. Beckwith was dressed as a Spanish dancer. Her gown was all of red and gold, with spangles about the neck and arms, and she carried castanets and wore pretty red slippers. Mr. Carroll Beckwith was dressed as a white monk, having a big cowl hanging down the back from his neck and a rope girdle about his waist.

Mr. and Mrs. Cooper Hewitt appeared in the uniform of the Salvation Army. Mrs. Cooper Hewitt was a true Salvation Army lassie, but her gown was better fitting and more elaborate than any to be seen in the Fourteenth street headquarters. Her husband wore the regulation Salvation Army cap.

Mr. Stanford White also wore the uniform of a Salvation Army officer.

When Reginald de Koven appeared in the guise of Herr Most, his entry was greeted with a roar of laughter. He wore a red wig and a ragged beard, and carried what looked like a full-fledged dynamite bomb in his hand. Mrs. Reginald de Koven wore the costume of a Spanish dancer, and her gown was much admired.

Miss Breese, a sister of James Lawrence Breese, the host, came in the dress of a nun. The Breeses are Roman Catholics, by the way, while Mrs. Breese is a niece of Bishop Potter.

Mr. Elliott Gregory wore one of the most striking costumes of the evening. He appeared as a French tough. He had on a tall hat made of batiste, bulging out at the top, and with a peak in front. He wore a velveteen coat, and his plaid trousers were very loud, indeed. They belled at the bottom and nearly covered his shoes. A flaring red necktie complete this unique costume.

Mr. Duncan Cameron was another picturesque figure. He went as the Journal’s Yellow Kid. His big yellow shirt reached almost the ground, and the sleeves were so long that they hung down over his hands. Somehow or other his ears had been fixed so that they stood out from his head just as they do in Outcault’s pictures in the Sunday Journal.

Mr. Worthington Whitehouse was more dignified in the dress of a cardinal, recalling to many minds the elegant form of Richelieu.

Mr. George Bird came as a Spanish toreador, with a short little jacket edged with balls of velvet and trimmed with silver braid, a wide, gorgeous sash about his waist, tight breeches and silver-buckled shoes. The dress of Mr. James J. Van Alen, that of a burgomaster, was handsome and elaborate, and Mr. J.H. Purdy was well made up as Svengali.

One of the most striking costumes among the ladies was that of Mrs. Pierre Lorillard Ronalds, who was Miss Bertha Perry, of New York, before her marriage. She went to the midnight revel dressed as a schoolgirl. Mrs. Ronalds is small and pretty, and her short, simple gown harmonized well with her style of beauty.

Equally striking was the costume of Mrs. Harry McVicker. She was dressed as a French peasant girl, and her costume was a dream of quiet, harmonious colors.

Perhaps the most striking of the ladies’ costumes was that of Miss Virginia Fair, a sister of Mrs. Hermann Oelrichs. She appeared in the guise of Folly. Her dress was of bicycle length in three colors, of satin, with parti-colored strips. She wore low neck and short sleeves and little bells that jingled merrily as she walked, were hung about the gown. This was pronounced the handsomest costume of the evening.

Mrs. John Cowdin, formerly Miss Gertrude Cheever, wore a brilliant red dress and an enormous hat, forming the costume of “The Girl from Paris.” Mrs. Leslie Cotten was dressed as a simple schoolgirl.

Mrs. James W. Girard, Jr., appeared as a Hungarian officer, and Mr. Robert (?) as a Hindoo priest.

And that was the first of this season’s society evenings at Mr. Breese’s studio.

The article concludes with a recounting of the infamous “Pie Girl Dinner”, held the previous year at the Breese Studio.

- Mrs. George De Forest: Anita Hargous De Forest: 1857-1932. DeForest, along with her husband George, who was a trustee of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, were members of “The Four Hundred”.

First impressions of the party appeared almost immediately, most likely with some mistakes due to hasty reportage. This account also appeared in Hearst’s New York Journal for Saturday, December 19, 1896:

WINE PUTS OUT A BLAZING DRESS.

Mrs. George B. de Forrest Has a Narrow Escape at an Unique Frolic.

Champagne Bottles Seized and

Broken to Quench the Spreading Blaze.

Almost a Tragic Ending for a Decidedly

Fancy Dress Affair at “Jimmy” Breese’s Studio.

SOCIAL CREME DE LA CREME PRESENT.

Host Was Dressed as a Turk, His Studio Was a Cafe Chantant, and Society Belles Were the Bar maids.

This Is the tale of a fashionable frolic that very nearly ended In a tragedy. All of the participants in the affair were sworn to secrecy, but as murder will out, so will fire. The fire which sobered the spirits of the frolickers and threw some of the grandes dames present into hysterics, consumed part of the very fetching fancy toilette worn by Mrs. George B. de Forrest. As no water was available, the flames were extinguished with champagne.

The scene of the revel, which so narrowly escaped ending disastrously, was the studio of James Lawrence Breese, at No. 5 West Sixteenth street. Mr. Breese is a product of Tuxedo, and is a decided original. As such he is persona grata in the fashionable world, where novelty Is at a premium. Having attained high proficiency as an amateur photographer, he adopted that craft as his field of labor, and became the fad of the hour. His “carbon studio” Is a favorite resort of the Four Hundred, and is made the scene of periodical entertainments, which are designed to be unique.

Such an entreatment was given In the small hours yesterday morning, when the unprogrammed conflagration of Mrs. de Forrest’s skirts added to the occasion a feature more deserving the qualification “unique” than the quaintest of Mr. Breese’s inventions. The host received his guests in the costume of an Arab sheik. He is a man of commanding presence, with a dark beard, and looked the part very well. Indeed. Mrs. Breese, made up as a Spanish dancing girl, helped him to welcome the guests.

They were a gay and a picturesque horde who invaded the studio as the clock struck twelve. James J. Van Alen and Hermann Oelrichs Impersonated Dutch burghers; Winthrop Chanler and Miss Wilmerding posed as members of the Salvation Army and rattled their tambourines incessantly: James Gerard, Jr, was a handsome Hungarian hussar: Craig Wadsworth and Willie Tiffany were court jesters; Miss “Birdie” Fair wore the ruff of Folly: Cooper Hewitt and Whitney Warren were turbaned Turks: Creighton Webb’s well-known legs were displayed to advantage beneath & long Spanish cloak: Dickie Peters was as proud of his appearance in a suit of pajamas and a high hat as if he had uttered it epigram; Mrs. de Koven wore a Spanish costume and danced; Miss Elsie Clews was a Swiss peasant, Miss Duer a French marquise; Miss Hoffman an Assyrian dancer, Elliott Gregory a French costermonger, George Munzig was Paderewski. Harry McVickar an Eton schoolboy, and Edward Crowninshield a clown.

Loud were the expressions. of delight when it was perceived that the irrepressible Breese had fixed up his studio to represent a cafe chantant, for there is nothing delights the fashionable world more than to play at being real questionable and shady. But that was not all. The illusion was carried to an amazing extent, and when the guests had stopped laughing at the result, they murmured: “How clever! Oh, Mr. Breese, how well you do these things!” In addition to the costumed guest, there were four real black men in Oriental garb, and five real Armenians from Coney Island.

But nobody paid much attention to these people, when there was so much that was artificial to be admired.

The cafe chantant entertainment was as good as such society imitations generally are. Mrs. Carroll Beckwith, the wife of the artist, sang Spanish songs. Mrs. J. Clinch Smith did plantation dances in a salmon pink dress, with her face blacked. One of the guests impersonated Li Hung Chang, and “guyed” individuals among his audience.

It was just after supper that the real excitement occurred. During the repast many “original” pranks were played, among others the scattering abroad of matches. Mrs. George B. de Forrest trod on one of these matches when she arose from the table and it ignited.

The next instant a sheet of flame shot up the front of her fluffy white skirt. She screamed, and so did everybody else. Half a dozen men shouted half a dozen different directions. Mrs. de Forrest showed a disposition to rush from the studio, but before she could reach the door she was unceremoniously tripped up by Stanford White.

“Water! Water!” shouted Worthington Whitehouse, who was dressed in the scarlet robes of a cardinal. But there was not so much as a pint of water in the studio. In this emergency some genius conceived the idea of quenching the flames with champagne, of which there was no lack. The rest of the company grasped quickly at the idea, and the necks had been knocked off half a dozen bottles in a moment. The sparkling liquid proved an efficient extinguisher, and Mrs. de Forrest was soon led-sobbing, trembling, with the remnants of a charred skirt clinging to her-to recover her composure in her hostess’s apartment.

And everybody agreed that “Jimmy” Breese had indeed given a unique entertainment.

✻ ✻ ✻ ✻ ✻

James Lawrence Breese: 1854-1934

James Lawrence Breese, a stockbroker by profession, owned and operated The Carbon Studio, located on the ground floor of his townhouse at 5 West 16th street in New York City in partnership with American photographer Rudolf Eickemeyer Jr. Breese, a member of New York Society himself, specialized in Society portraiture as well as the copying of artwork.

The following biography of Breese is courtesy of his great great grandson Mark Sink, a noted American photographer based in Denver, CO. Mark maintains a blog on Breese and extended family here.

James L. Breese and the Carbon Studio NYC

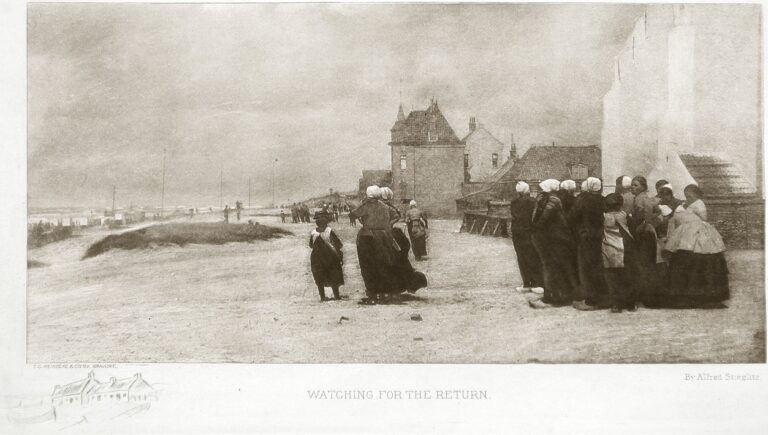

He was James L. Breese, best friend of architect Stanford White who did design work for both his New York townhouse and studio at 5 West 16th street and his Southampton country estate (both still standing). He was the nephew of the portrait artist, inventor of the telegraph and co-founder of the National Academy of Design, Samuel Finley Breese Morse (aka “The father of American Photography”). He was a leading light in New York’s turn-of-the-century social and artistic upper crust. James L. Breese owned and operated the Carbon Studio in partnership with pictorialist Rudolf Eickemeyer Jr., who later became a member of Alfred Stieglitz’s The Photo Secession and The Linked Ring. Breese’s then famous “One of 1001 Nights” salons would begin at midnight, at 5 West 16th, “at the foot of women’s mile.”Artists, writers and society secretly gathered for lascivious intrigue. The documented and published highlights were dresses catching fire to be extinguished with champagne, “The Pie Girl Dinner”, a naked sixteen year old girl to popping out of a pie, and “the girl in the red velvet swing.” His circle of bohemian friends and guests included such remarkable personalities as Miss Emily Hoffman, the mother of Diana Vreeland, (Charles) Dana Gibson, Louis Saint Gaudens, John Singer Sargent, Nicola Tesla, Otho Cushing, Miss Post, the Parsons, the DeForests, Evelyn Nesbit and many more. Together they staged elaborate historical party tableaux which Breese photographed for his private amusement. He was the founder and an active member of the NY Camera Club, won many awards, and was cataloged in Camera Notes many times. He and Stieglitz were the only two Americans (out of sixty American applicants) to be accepted in an exhibition in Vienna 1893, (1891-editor) which Breese took first prize. He wrote and illustrated articles for Cosmopolitan (1894), one titled The Relationship Of Photography To Art. He was heavily chronicled and his exhibitions reviewed during his day. The most noted was by critic Edward L. Wilson, who wrote of Breese and his work, “true and interesting picture qualities” and, “the leader of New York’s new school.” Another review by Sadakichi Hartman gushes about Breese and pans Stieglitz. Like so many of his contemporaries very little is known about him today. The well known historians, William Welling, Christian A. Peterson and the director of the National Portrait Gallery, Mary Panzer, have all made generous entries about Breese in their historical texts and publications of the period and they all agree there is much more to be unearthed and brought to light about this bohemian group that called themselves “The Carbonites”.

✻ ✻ ✻ ✻ ✻

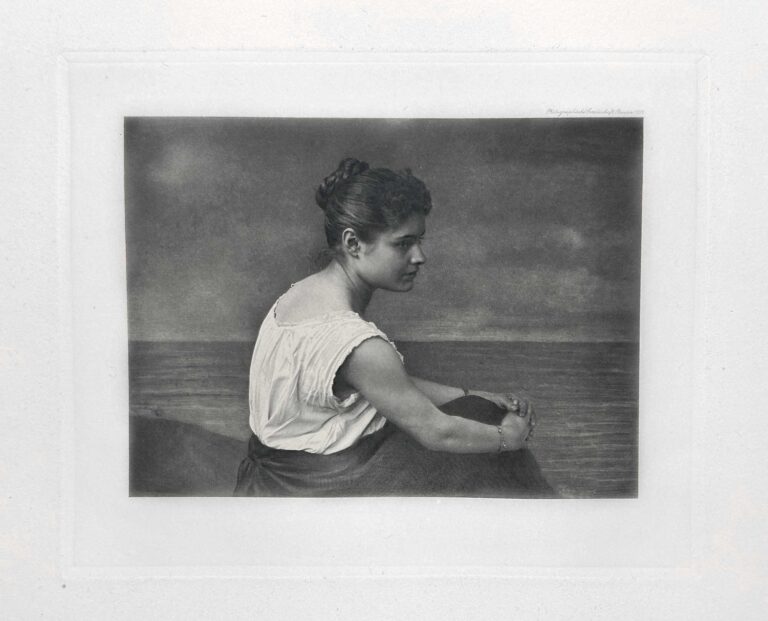

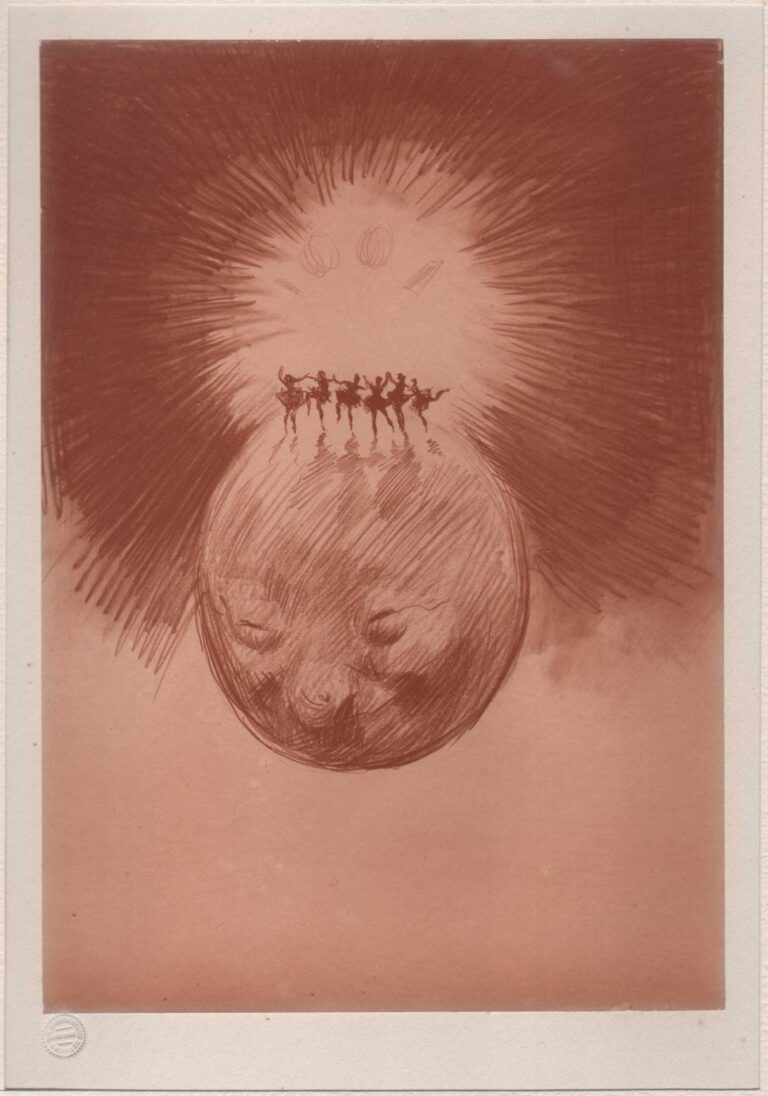

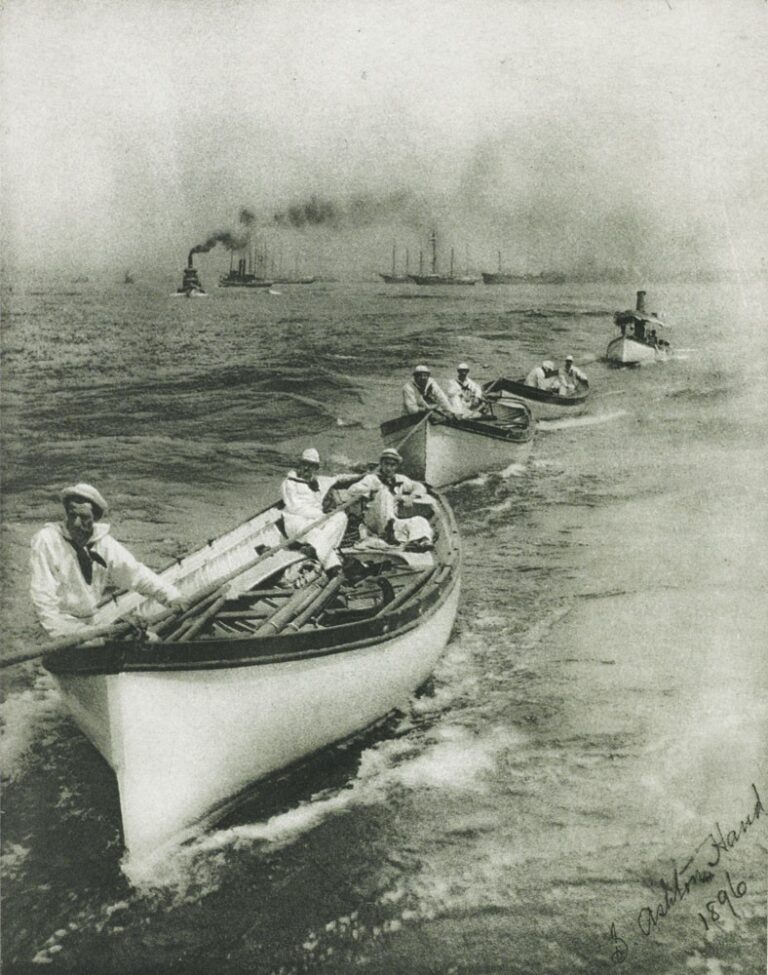

The 1001 Nights Portfolio: One of perhaps only 50-70 copies produced, with almost all believed to be either lost or destroyed, this rare mammoth album of original carbon photographs, including of artwork produced by notable artists and an original multi-color lithograph, was compiled by amateur photographer James Lawrence Breese in early 1897. An important and historical photographic and artistic record of America’s Gilded Age, it was produced as a lavish “souvenir” album of a gathering of 70 invitees of the New York City elite, including members of The Four Hundred. The occasion was a costume party at the photographer’s “Carbon Studio” and townhouse at midnight on December 17, 1896.

The album contains ten carbon prints, laid down on oversized cards and individually matted, all with Breese’s “The Carbon Studio” blindstamp, and an original lithograph of the party’s “menu” printed in colors by American artist Robert Lewis Reid. (1862-1929)