Discovering a needle in a haystack, with apologies to this farmhand happily lounging atop a salt marsh haystack before the turn of the 20th century, is the proverbial sensation one beholds when encountering a fine blueprint, or cyanotype photograph, for the first time.

Detail: “Farmhand atop Salt Marsh Haystack” : anonymous American photographer: cyanotype: 1895-1900: 8.7 x 12.0 cm: The location of this photograph has been determined to be Plum Island in Newburyport, Mass, on Boston’s North Shore. The marshes, in a tidal zone on the Atlantic ocean, is where salt marsh hay grows and then harvested. The farmhand would first use the wooden drag rake to collect the cut hay into piles. It would then be gathered and piled into layers above a platform (seen at bottom of photo) made from cedar wood staddles. This form of haystack making dates from the 17th Century is still practiced in the area in the present day. From: PhotoSeed Archive

Given the excuse the Worcester Art Museum in Massachusetts is devoting significant wall space to their current exhibit: Cyanotypes: Photography’s Blue Period, (through April 24, 2016-publication here.) all while keeping with this institution’s admirable mission of presenting photography as an art form to the public since 1904, I’m mounting my own mini-exhibition of vintage cyanotypes from the PhotoSeed archive here with the added bonus of several photographs that literally embrace and further the definition of “blue print”. So like our “prince” above, whose raking abilities are indeed most impressive, here’s hoping your own photographic gatherings include finding the unique beauty these gems in blue offer.

-David Spencer, February, 2016

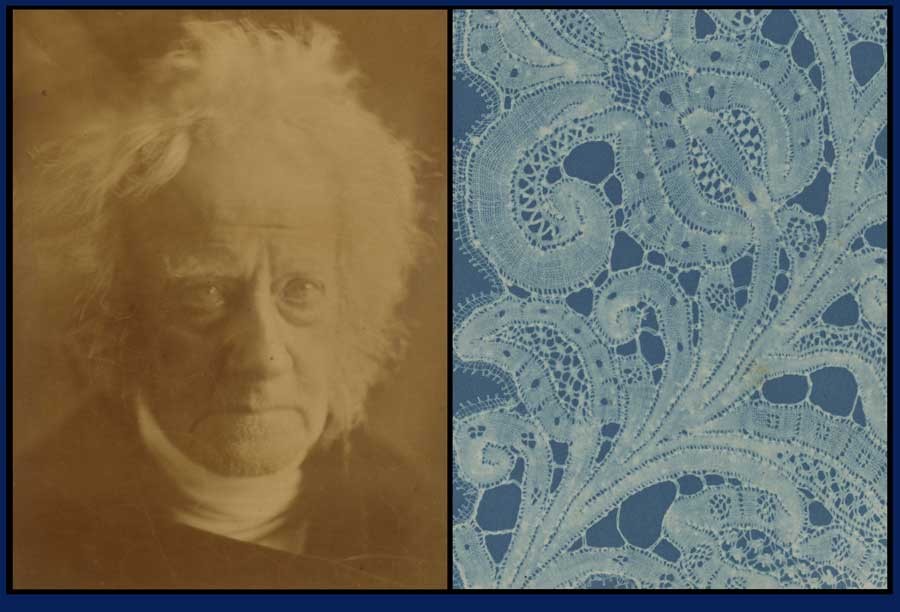

Left: Detail: “John Frederick William Herschel”(1792-1871): Julia Margaret Cameron: British: Albumen print: 1867: image: 35.5 x 27.1 cm (sight): The Cyanotype, or blueprint process, was first invented by John Herschel in 1842. It involves first exposing a negative, oftentimes through the contact print method with paper (or even cloth or another matrix) first treated with ammonium ferric citrate. In daylight, the matrix is then developed using a solution of potassium ferricyanide. The resulting print reveals itself as a brilliant blue hue known as Prussian blue. (ferric iron compounds being changed into ferrous iron). From: PhotoSeed Archive. Right: Detail: “Braid and Thread Lace”: Julia Herschel: British : (1842-1933 ) : cyanotype: 1869 or before. It’s intriguing to know the inventors daughter used the process herself (John Herschel was known to only use his blueprint process to reproduce notes and diagrams) to create artistic statements, like this original photograph bound with the volume: A Handbook for Greek and Roman Lace Making published in London in 1869 and printed by R. Barrett and Sons. From: Spencer Collection, The New York Public Library. “A handbook for Greek and Roman lace making” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1869. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/7dd58e00-0898-0133-038f-58d385a7bbd0

Left: Detail: “Title Page”: from: Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions: Anna Atkins: British: (1799-1871) : cyanotype: 1843-1853. This title page in the author’s own hand is part of a multi-part volume of 231 original cyanotypes featuring contact prints of British seaweed specimens first copied on individual glass sheets by William Henry Fox Talbot’s photogenic drawing method by Atkins and then reproduced by John Herschel’s newly invented cyanotype or blueprinting process. The importance of the work is summed up by The New York Public Library, which owns this rare volume formerly in the library of Herschel: “Photographs of British Algae is a landmark in the histories both of photography and of publishing: the first photographic work by a woman, and the first book produced entirely by photographic means.” From: Spencer Collection, The New York Public Library. “Titlepage.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1843 – 1853. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47d9-4af4-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99. Right: Detail: “Sargassum plumosum”:from: Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions: Anna Atkins: British: (1799-1871) : cyanotype: 1843-1853. These beautiful seaweed specimens was the second plate in the pagination for Vol. 1 of “British Algae”. From: Spencer Collection, The New York Public Library. “Sargassum plumosum.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1843 – 1853. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47d9-4af6-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

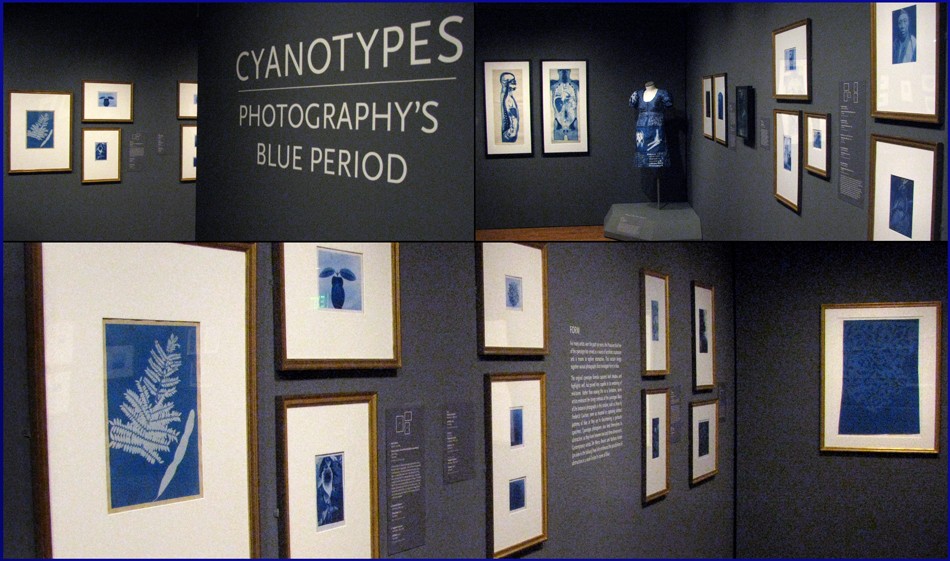

Composite: April, 2016 installation photographs from exhibit: “Cyanotypes: Photography’s Blue Period” at the Worcester Art Museum in Worcester, MA. Running from January 16-April 24, 2016, the show was the first comprehensive exhibit on the medium of cyanotype ever held in the United States. Vintage examples from the museum’s own holdings as well as loans from other institutions and private individuals spanned the period from the 1850’s to the first decade of the 21st Century. The exhibit was curated by Nancy Kathryn Burns, Assistant Curator of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs at the museum & Kristina Wilson, Associate Professor of Art History, Clark University. Both additionally edited the volume: “Cyanotypes: Photography’s Blue Period” published by the museum: ISBN# 978-0-936042-06-0. Installation photographs by David Spencer for PhotoSeed Archive

Detail: “Sailboat near Plum Island” : anonymous American photographer: cyanotype: 1895-1900: 9.2 x 12.5 cm: The location of this photograph has been determined to be Plum Island Sound (the Parker River) in Newburyport, Mass, on Boston’s North Shore. In the distance can be seen many salt marsh haystacks. From: PhotoSeed Archive

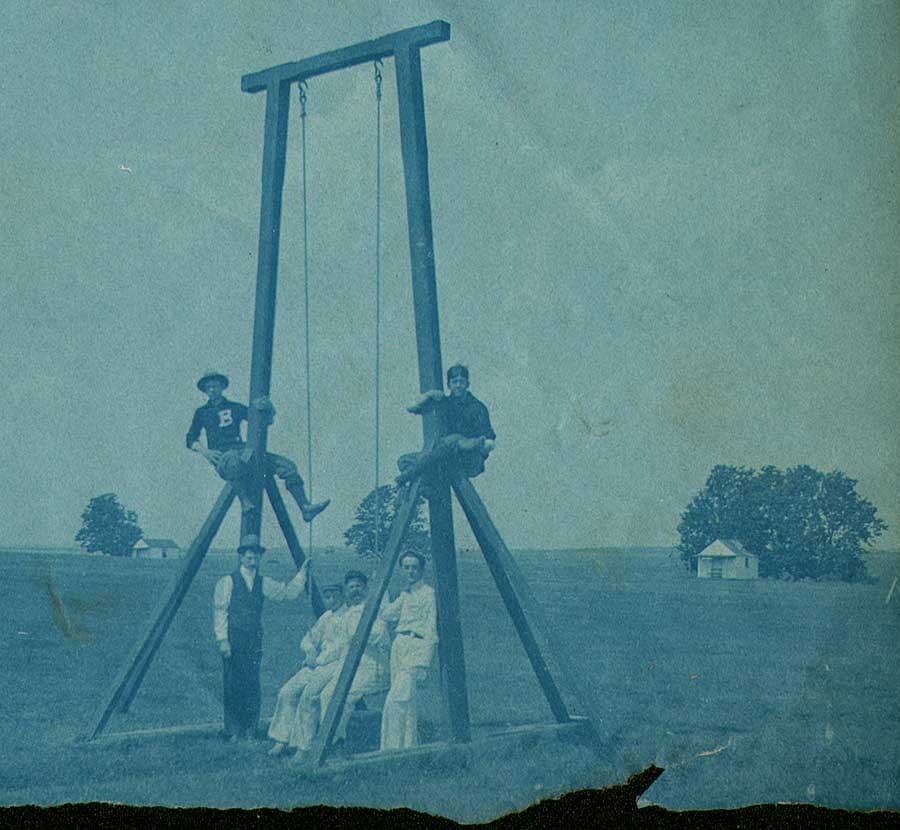

Detail: “Portrait Grouping with Tall Wooden Swing” : anonymous American photographer: cyanotype: 1895-1900: 8.5 x 11.5 cm: Most likely taken within the Plum Island area of Newburyport, Mass., (by the same photographer as it was included in small album of views as previous post photographs) this intriguing photograph shows an oversized wooden swing within a mowed field. One theory for the size of this swing would be because tidal changes could submerge the structure. Note lower margin of photograph where it was torn to fit a pre-cut window within a small album. From: PhotoSeed Archive

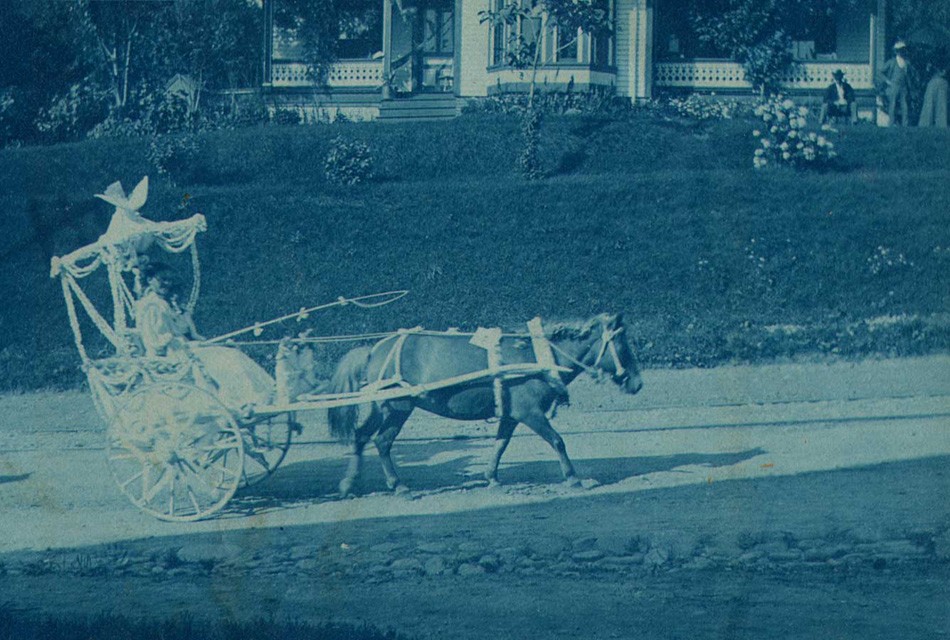

Detail: “Pony Cart in Parade” : anonymous American photographer: cyanotype: 1895-1900: 8.8 x 11.4 cm: Most likely taken in or near Newburyport, Mass., (by the same photographer as it was included in small album of views as previous post photographs) this slice of small-town American life shows a pony pulling a floral-decorated cart guided by a young lady traveling down a dirt road, perhaps on Memorial Day. Above can be seen a Victorian home with three parade watchers who stand at upper right. A set of trolley tracks can be seen in road beyond horse. From: PhotoSeed Archive

Detail: “Woman in White Dress Standing next to Chair” : anonymous American photographer: cyanotype: 1895-1900: 8.3 x 8.5 cm: Her name perhaps lost to history, a young woman wearing a white dress stands on a porch and looks away from the camera: a most unusual genre pose indicating she may have been playing a role of some type: for a play? or as an honored guest who had taken part in the parade depicted in the previous photograph? This view also likely taken in or near Newburyport, Mass. (and was included in the same small album of views as previous post photographs) From: PhotoSeed Archive

Detail: “Portrait Study near Window” : anonymous American photographer: cyanotype: 1899: 9.7 x 6.3 cm: Most likely sisters, this moody interior portrait is unusual for amateur work of the period because the photographer instructed his subjects to avert their gaze to the camera. The woman at left holds what is believed to be a folded fan while her companion holds a ball of yarn in her lap. Photograph may have been additionally printed on commercially available presensitized Venus paper manufactured by the Peerless Blue Print Co., as it was included in a cardboard box of this brand with an expiration date of 1899. Location for this image may have been the midwestern United States, as it was included in this Peerless box of loose cyanotypes purchased from an Indiana seller. From: PhotoSeed Archive

Detail: “Favorite Chair near Window” : anonymous American photographer: cyanotype: 1899: 9.4 x 12.0 cm: Another moody interior portrait, this time absent of any human subjects, is nonetheless interesting due to the feeling it evokes with the framed portrait of the bearded gentleman on the wall above what might be or was his favorite living room cushioned chair. Photograph may have been additionally printed on commercially available presensitized Venus paper manufactured by the Peerless Blue Print Co., as it was included in a cardboard box of this brand with an expiration date of 1899. Location for this image may have been the midwestern United States, as it was included in this Peerless box of loose cyanotypes purchased from an Indiana seller. From: PhotoSeed Archive

“Schoolteacher at Desk” : anonymous American photographer: cyanotype: 1899 or before: 10.5 x 9.1 cm: With slight motion blur seen in her face, a schoolteacher holding a pencil works on papers at her desk in front of a large blackboard listing student lesson plans including Arithmetic, Geography (Europe topical review) and Language, (Punctuation-4 rules) with additional lesson plans at left outlining sentence structures. The 1896 volume: The War in Cuba, Being a Full Account of Her Great Struggle for Freedom can be seen on the desk at left. A chalk drawing of holly leaves is at very top of blackboard, so view may date to the Christmas holiday of 1898. Photograph may have been additionally printed on commercially available presensitized Venus paper manufactured by the Peerless Blue Print Co., as it was included in a cardboard box of this brand with an expiration date of 1899. Location may have been the midwestern U.S., as it was purchased with other cyanotypes from an Indiana seller. From: PhotoSeed Archive

“Man with Bowler hat at Desk”: : anonymous American photographer: cyanotype: 1899: 6.5 cm round | 11.3 x 8.8 cm: Possibly a self-portrait, a man wearing a bowler hat seated next to a desk stares away from the camera. A calendar featuring artwork of a horse preparing to pull a two-wheel cart dated January, 1899 hangs on the wall. Photograph may have been additionally printed on commercially available presensitized Venus paper manufactured by the Peerless Blue Print Co., as it was included in a cardboard box of this brand with an expiration date of 1899. Location may have been the midwestern U.S., as it was purchased with other cyanotypes from an Indiana seller. From: PhotoSeed Archive

Detail: “Mother cooks at Point O’ Woods LI”: Charles Rollins Tucker: American: cyanotype: 1899: 12.5 x 17.3 cm: Mary (Carruthers) Tucker,(1870-1940) the spouse of amateur photographer C.R. Tucker, cooks on the beach at Point O’Woods. Wikipedia states this private retreat-even today- may have been the first settlement on Fire Island in Long Island Sound, and was originally organized in 1894 for religious retreats, some from the Chautauqua assemblies before ownership passed to the present-day Point O’ Woods Association in 1898 after the first group went bankrupt. From: PhotoSeed Archive

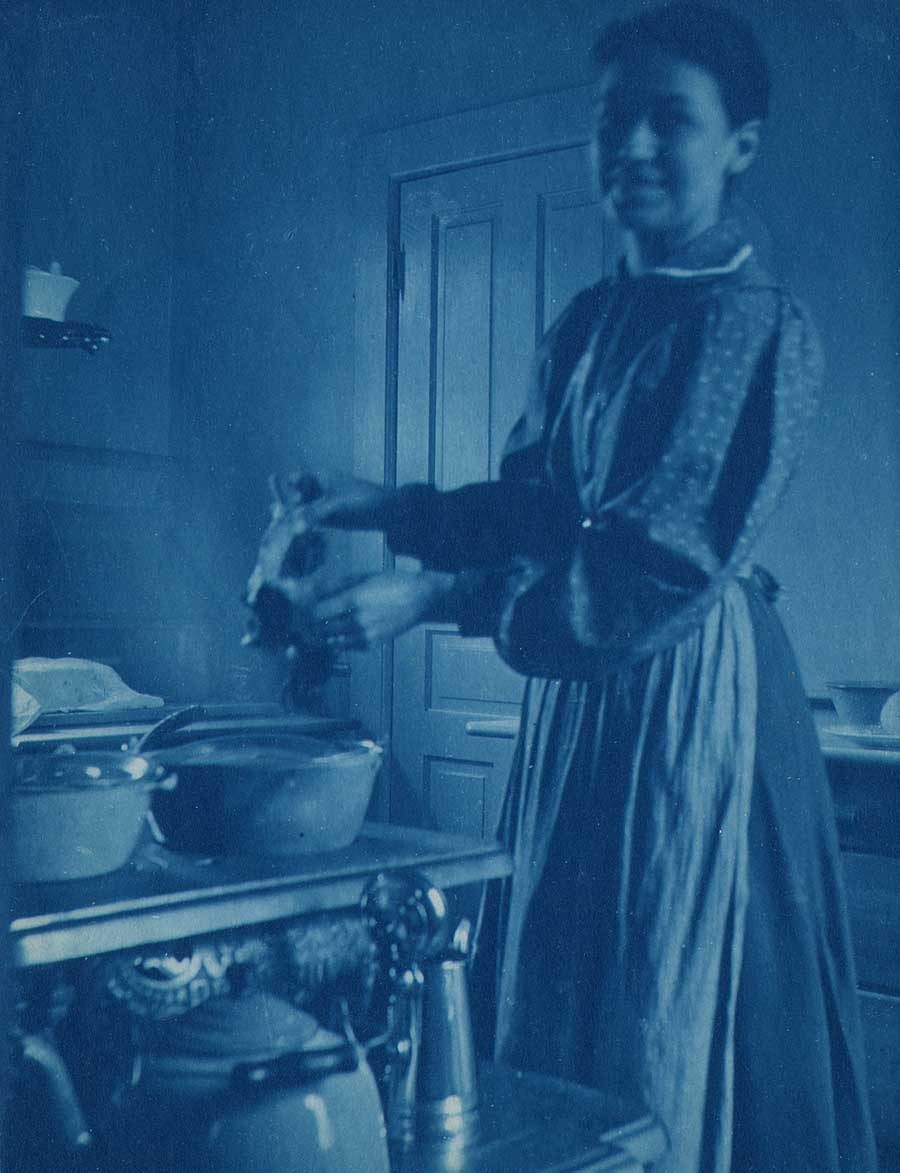

“Woman working in Kitchen” : anonymous American photographer: cyanotype: 1899: 11.9 x 9.2 cm: Wearing an apron and looking towards the camera, a woman prepares to place some type of food into a pot on a shelf above a stove while working in a home kitchen. Photograph may have been additionally printed on commercially available presensitized Venus paper manufactured by the Peerless Blue Print Co., as it was included in a cardboard box of this brand with an expiration date of 1899. Location may have been the midwestern U.S., as it was purchased with other cyanotypes from an Indiana seller. From: PhotoSeed Archive

Detail: “Picnickers enjoy a Meal”: anonymous American photographer: cyanotype: 1899: 8.0 x 10.6 | 9.9 x 12.5 cm: A party of seven fashionably-dressed men and women enjoy a picnic outing next to a lake. Photograph may have been additionally printed on commercially available presensitized Venus paper manufactured by the Peerless Blue Print Co., as it was included in a cardboard box of this brand with an expiration date of 1899. Location may have been the midwestern U.S., as it was purchased with other cyanotypes from an Indiana seller. From: PhotoSeed Archive

Detail: “Horseback Trail Ride”: anonymous American photographer: cyanotype: 1899: 9.0 x 11.2 cm: Two men on horseback, who appear to be in military uniform at left, and a woman rider wearing mosquito netting over her hat and accompanied by a canine Whippet, stop for a moment in sunlight on a rural forest riding trail. Photograph may have been additionally printed on commercially available presensitized Venus paper manufactured by the Peerless Blue Print Co., as it was included in a cardboard box of this brand with an expiration date of 1899. Location may have been the midwestern U.S., as it was purchased with other cyanotypes from an Indiana seller. From: PhotoSeed Archive

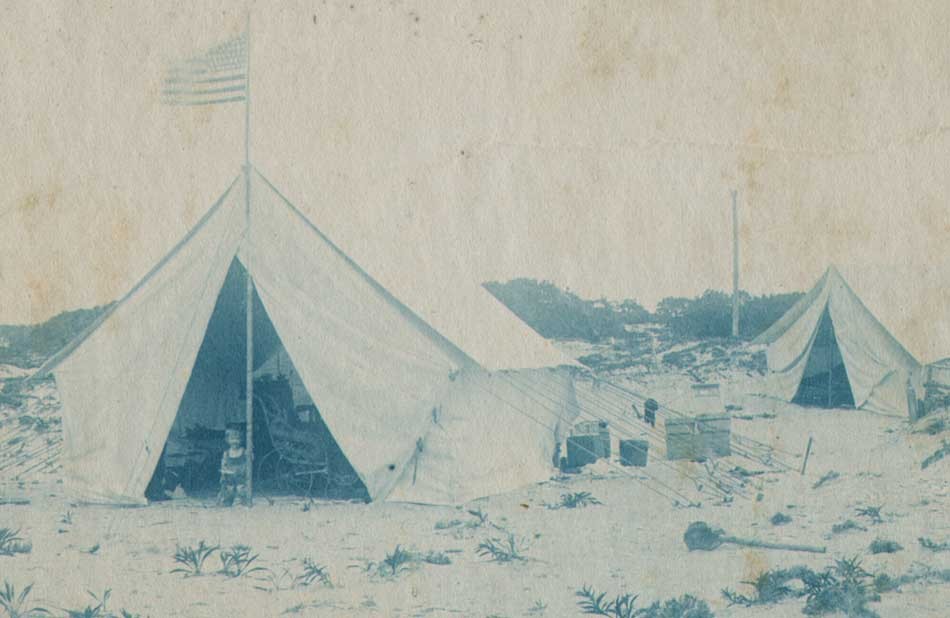

Detail: “Dorothy Tucker at Point O’ Woods Beach Camp”: Charles Rollins Tucker: American: cyanotype: 1901: 11.5 x 17.5 cm: Dorothy Tucker, (1899-1986) who appears to be no older than two years old, the young daughter of amateur photographer C.R. Tucker, stands at the entrance to a large canvas tent with American flag flying overhead on the beach at Point O’ Woods. Wikipedia states this private retreat-even today- may have been the first settlement on Fire Island in Long Island Sound, and was originally organized in 1894 for religious retreats, some from the Chautauqua assemblies before ownership passed to the present-day Point O’ Woods Association in 1898 after the first group went bankrupt. From: PhotoSeed Archive

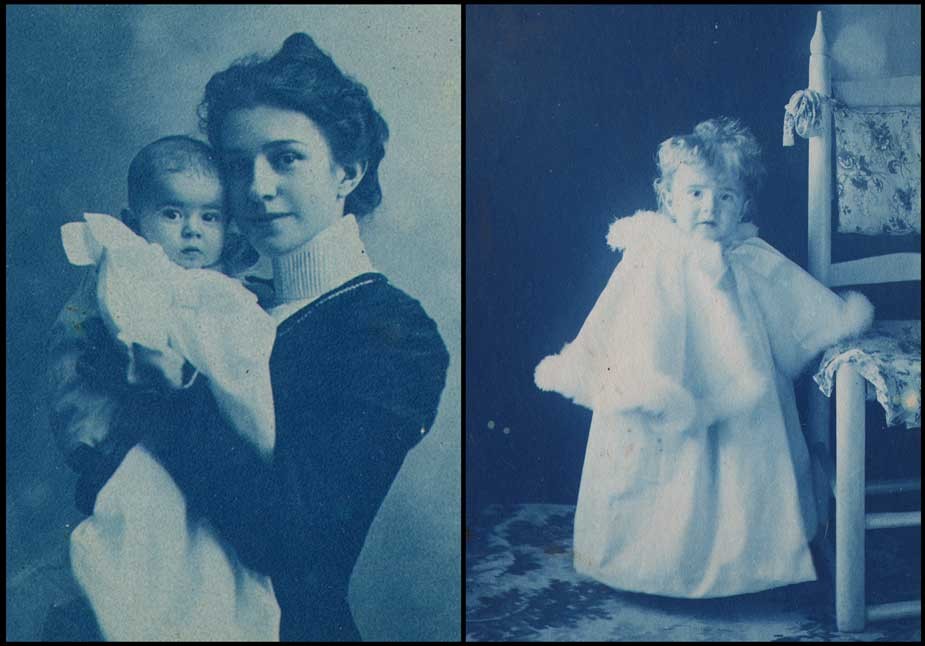

Left: Detail: “Baby Dorothy Tucker with Mother”: Charles Rollins Tucker: American: cyanotype: 1899: 7.0 x 5.4 cm: Right: “Dorothy Tucker dressed in Fur-Trimmed Coat Next to Chair”: Charles Rollins Tucker: American: cyanotype: 1900: 12.2 x 8.6 cm: Born in August of 1899 on New York’s Staten Island, Dorothy Tucker was a constant subject for her father-a high school physics teacher at Curtis High School on the island-who trained his camera on her from birth to late teens. As a cyanotype, the photo showing Dorothy with her mother Mary Tucker (1870-1940) at left was thought well enough to frame behind glass as a family keepsake, lending credibility to the fact the process was not just considered a first way of proofing photos before a final selection was made. Instead, with the sequence shown in this post of four formal portraits of Dorothy as cyanotypes, the process was readily embraced by certain amateurs like Tucker. Both from: PhotoSeed Archive

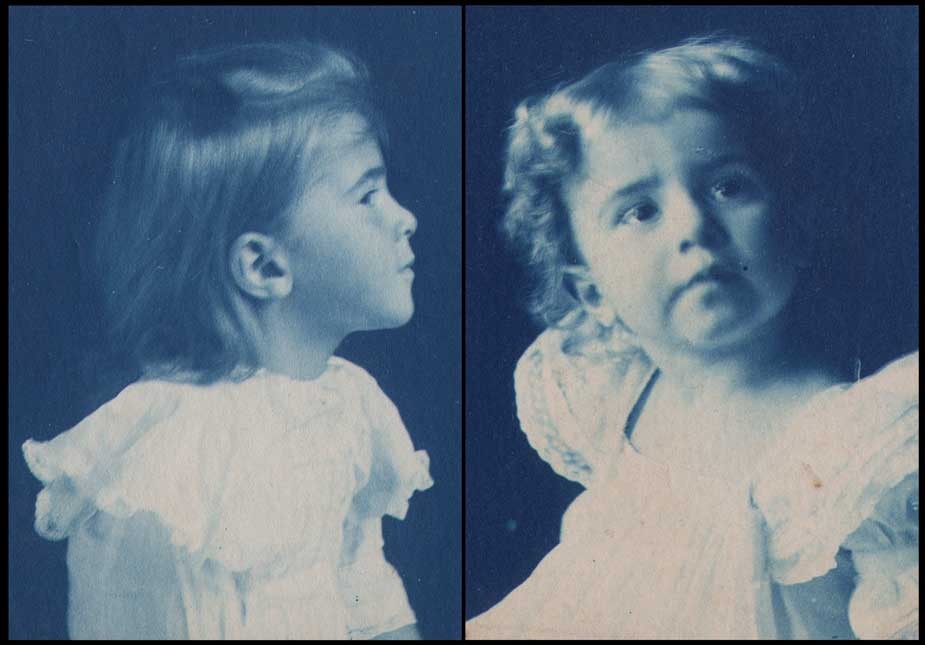

Left: “Dorothy Tucker Profile”: Charles Rollins Tucker: American: cyanotype: ca. 1903: 9.9 x 7.2 cm: Right: “Portrait of Dorothy Tucker”: Charles Rollins Tucker: American: cyanotype: ca. 1903: 9.3 x 6.9 | 17.8 x 12.8 cm. Born in August of 1899 on New York’s Staten Island, Dorothy Tucker was a constant subject for her father-a high school physics teacher at Curtis High School on the island-who trained his camera on her from birth to late teens. Unlike many of the examples of Dorothy held by PhotoSeed that lack a mount, the cyanotype portrait of her at right was center-glued to a gray exhibition card, with another variant example printed in platinum showing evidence of being exhibited. Both from: PhotoSeed Archive

“Dorothy Tucker with Fan”: presumed photographer: done in hand-inscribed, block letters: F.L.C.: American?: cyanotype: 1912: 16.5 x 8.6 | 22.0 x 11.3 cm: Shown presented within its tissue-guarded, ribbon tied folder, (22.6 x 12.3 cm) Dorothy Tucker, not quite 13 years old, strikes a pose with a fan inside her home on Staten Island, New York. She was most likely “performing” a part in a school play for “F.L.C.”, presumed to be the photographer of this work who was certainly an acquaintance of Dorothy’s amateur photographer father Charles Rollins Tucker. The presentation folder additionally dated in blue ink May 18, 1912 & annotated Dorothy Tucker in graphite along lower margin. From: PhotoSeed Archive

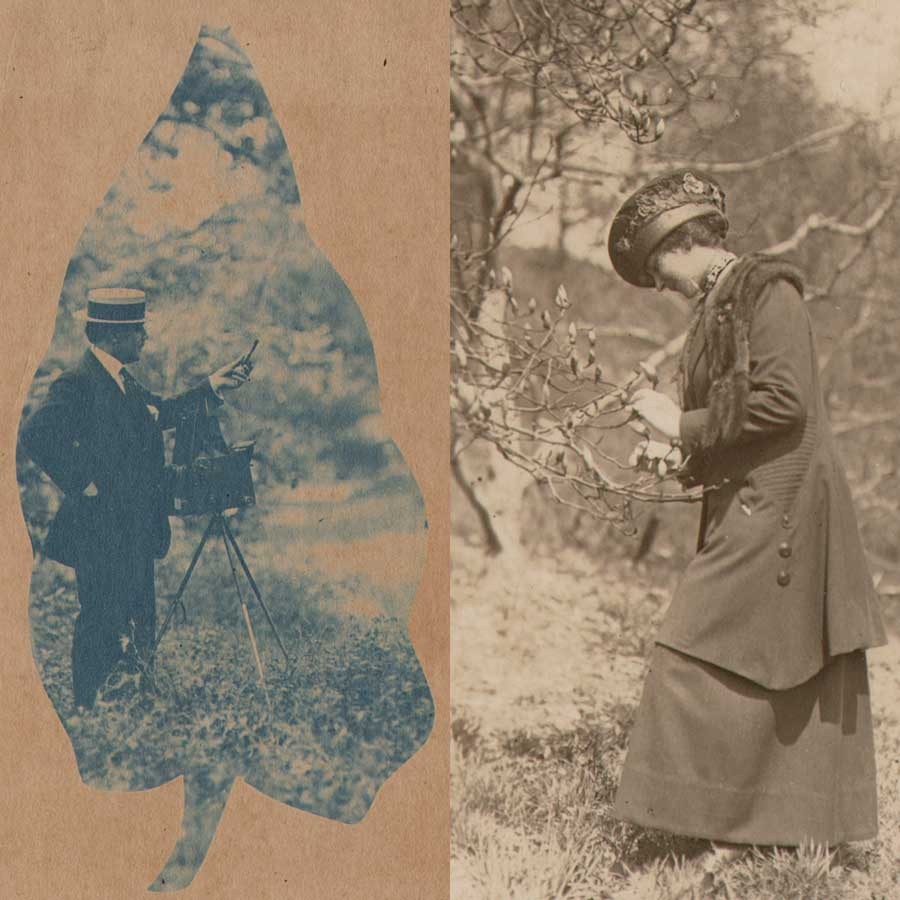

“White Birch Trees on Hill”: by Unknown Brooklyn (photographer) : American: cyanotype: ca. 1905-10: 11.6 x 8.8 | 16.8 x 12.3 cm: A tantalizing backdrop of an unknown city can be seen in the distance at right of this cyanotype image featuring several sturdy white birch trees scarred in several places by penknives declaring true love. Possibly with a location of Prospect Park in Brooklyn, this photograph, with title supplied by this archive, is by an Unknown Brooklyn amateur photographer whose surviving work was discovered in a trunk in the American South. Background can be found by searching for this site’s 2015 blog post: “No Junk in Trunk”. From: PhotoSeed Archive

“Swans in Mist”: by Unknown Brooklyn (photographer) : American: cyanotype: ca. 1905-10: 8.8 x 11.6 | 12.6 x 17.7 cm: Swans glide through mist on a lake in a park setting-possibly Brooklyn’s Prospect Park as many known examples of this location were taken by this photographer. This photograph, with title supplied by this archive, is by an Unknown Brooklyn amateur photographer whose surviving work was discovered in a trunk in the American South. Background can be found by searching for this site’s 2015 blog post: “No Junk in Trunk”. From: PhotoSeed Archive

“Dogwood Tree in Bloom”: by Unknown Brooklyn (photographer) : American: cyanotype: ca. 1905-10: 11.7 x 8.9 | 16.8 x 11.7 cm: A Dogwood tree blooms on the edge of a meadow in a park setting-possibly Brooklyn’s Prospect Park as many known examples of this location were taken by this photographer. This photograph, with title supplied by this archive, is by an Unknown Brooklyn amateur photographer whose surviving work was discovered in a trunk in the American South. Background can be found by searching for this site’s 2015 blog post: “No Junk in Trunk”. From: private U.S. collection.

“Man Standing Next to Linotype Machine”: unknown photographer: cyanotype: ca. 1895-1905: 11.9 x 9.6 | 13.2 x 10.6 cm: With the only annotation being the word Chicago written on the verso of this intriguing card-mounted cyanotype indicating origin, it’s interesting to note that blueprinting, in addition to recording mechanical drawings, was also commonly used to make a record of large machinery like this early Linotype machine, an invention that revolutionized the speed of printing, particularly for newspapers and magazines. Invented by the German-born Ottmar Mergenthaler, (1854-1899) who has an uncanny surviving photographic likeness to the gentleman appearing in this cyanotype, the Linotype was first commercially used by the New York Tribune newspaper in 1886 and was in use into the 1970’s, when it was largely replaced by offset lithography printing and computer typesetting. From: PhotoSeed Archive

And now, examples of “blue prints” owing their roots to the beauty of the cyanotype reproduced using alternate photo-mechanical and photographic processes:

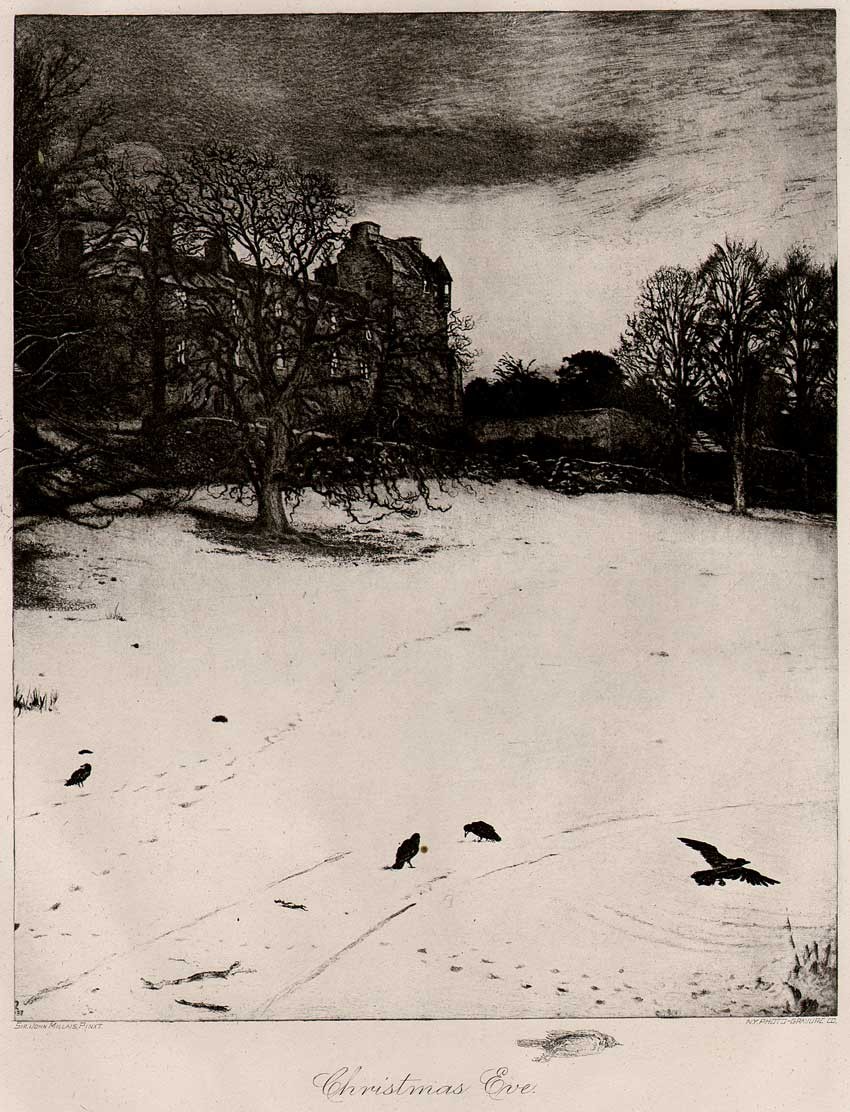

“Starlight”: Charles Edward Doty: American 1862-1921: blue-toned collotype published in periodical “Sun & Shade: An Artistic Periodical”: New York: January, 1890: whole #17: N.Y. Photo-Gravure Co.: 11.2 x 19.4 cm | 27.6 x 35.0 cm: The popularity of the cyanotype process gave reason for firms like the Photo Gravure Co. of New York to provide print runs for a larger audience of works like “Starlight” whose source imagery was originally a cyanotype. The model, said to be one Miss Emma McCormick, was photographed by Hamilton, Ohio portrait photographer Doty with outstretched arms against a backdrop of stars that were most likely added in the engraving process. Doty, according to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, which owns hundreds of his original photographs, went on to become the “official photographer of the United States government in Havana,” his duties included documenting the modernization of Cuba under American governorship. From: PhotoSeed Archive

“Bundling and Gathering Faggots”: Nestor Stekke: La Louvière, Belgium: blue-tinted collotype published in Sentiment d’Art en Photographie: Brussels,: Vol. II, No. 1, Planche 1: October, 1899: 16.1 x 22.3 | 26.5 x 37.2 cm: Featuring the work primarily of Belgian photographers but open to all, this folio-sized high-quality photographic plate publication, (The Feeling of Art in Photography) under the direction of Camille Smits with reproductions executed in collotype by Jules Liorel, featured the award winning work of pictorialists who entered monthly contests on a given theme judged by painter (M. Titz) and amateur photographer Van Gèle. Short-lived, Sentiment debuted in October, 1898 and ran until January, 1901 when it was renamed L’Art en Photographie . From: PhotoSeed Archive

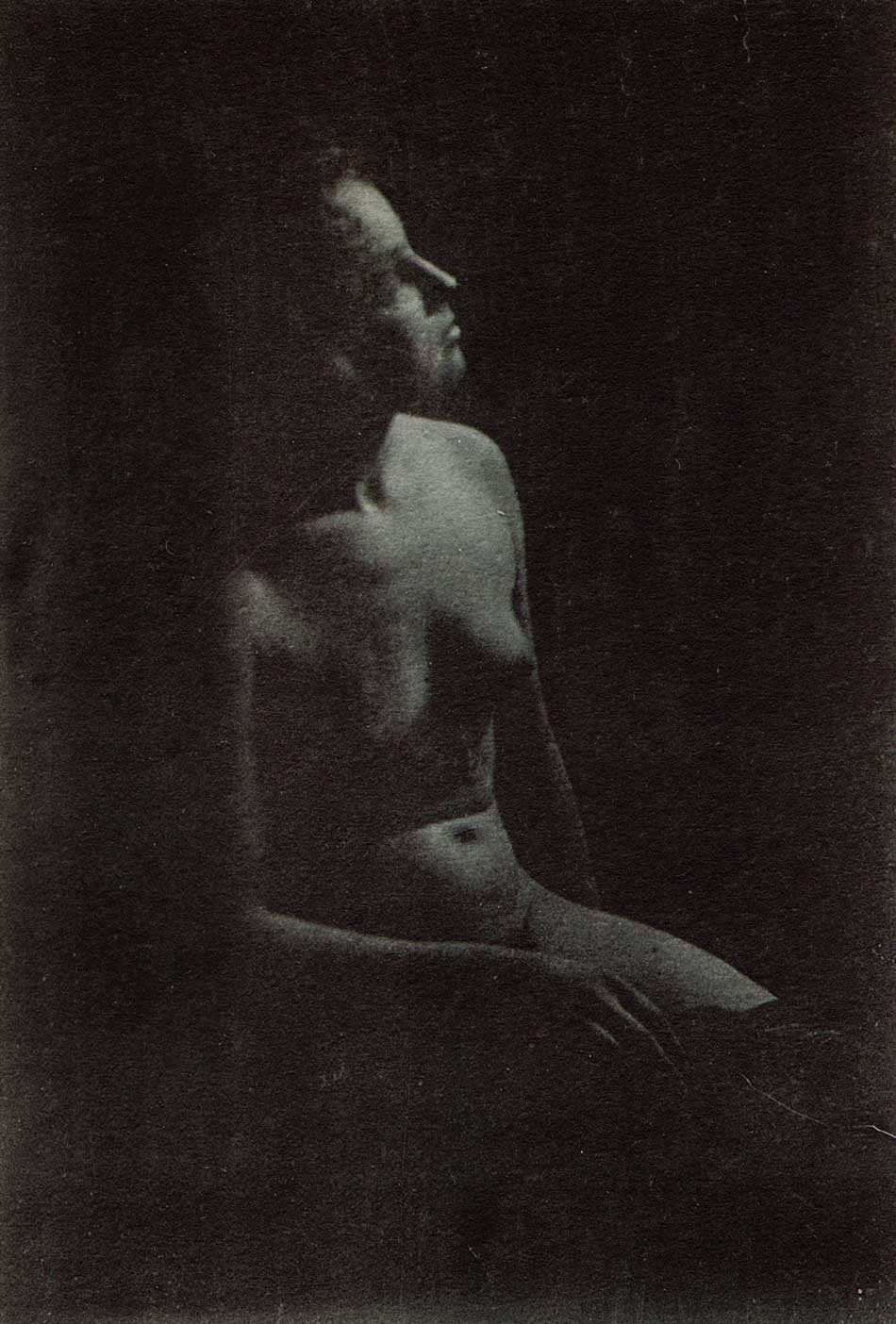

“Nude in Darkness”: Léon Sneyers: Belgium:(1877-1949) collotype published in L’Art en Photographie: Brussels: No. 8: August, 1901: 12.4 x 8.3 | 37.0 x 25.5 cm: Translated to “Art in Photography”, this folio-sized plate work was a continuation of “Le Sentiment d’Art en Photographie”, with primarily Belgian pictorialists entering their work in contests on a given theme. Published by Jules Liorel, who also printed the plates in his Brussels atelier, a bibliography of this monthly work states it was “undoubtedly inspired by “Die Kunst in der Photographie”, a German publication, and by “L’Art Photographique” published in Paris”. This observation was made in reference to the fine-quality plates issued with it, as in this female nude study by Sneyers taken in the shadows and printed effectively by Liorel in collotype using an ink color combining deep black and violet to compliment the closed eyes of Sneyer’s model. From: PhotoSeed Archive

“Fruit Seller on Scheveningen Pier”: Frank G.(eorge) Ensenberger, American: 1879-1966: blue-toned bromoil transfer print: 1910: 7.6 x 13.1 | 27.0 x 22.3 cm: A young woman balancing her load of grapes and other fruits for sale with a yoke stands on the Scheveningen Pier at the popular seaside resort located in The Hague in the Netherlands. In May, 1910, amateur photographer Frank Ensenberger of Bloomington, Ill sailed from Boston to Europe with his family, where he spent four months touring Great Britain, the Continent and other countries all while documenting the trip with his camera. On his return, approximately 900 selects were made by him and printed in various tints as bromoil transfer prints by an unknown professional photographer. They were gathered by country in leather-bound volumes, of which PhotoSeed owns nine. A prosperous business merchant and president of Ensenberger’s home furnishings store in Bloomington, the Bloomington Pantagraph newspaper wrote of his photographic efforts during the trip in September, 1910, commenting: “The proofs show Mr. Ensenberger possesses the rare instinct of recognizing the setting for a good picture when he sees it, many of the views being truly artistic.” Truthfully, his work was competent overall, with many of the plates being more “snapshot” in nature although documentary images scattered throughout the volumes show better than average compositional qualities. From: PhotoSeed Archive

“Children Portrait Group in Holland”: Frank G.(eorge) Ensenberger, American: 1879-1966: blue-toned bromoil transfer print: 1910: 7.6 x 13.1 | 27.0 x 22.3 cm: Standing in the middle of a roadway in Holland, a group of six children in their native dress stand for a portrait, the boys at right wearing traditional wooden shoes. In May, 1910, amateur photographer Frank Ensenberger of Bloomington, Ill sailed from Boston to Europe with his family, where he spent four months touring Great Britain, the Continent and other countries all while documenting the trip with his camera. On his return, approximately 900 selects were made by him and printed in various tints as bromoil transfer prints by an unknown professional photographer. They were gathered by country in leather-bound volumes, of which PhotoSeed owns nine. A prosperous business merchant and president of Ensenberger’s home furnishings store in Bloomington, the Bloomington Pantagraph newspaper wrote of his photographic efforts during the trip in September, 1910, commenting: “The proofs show Mr. Ensenberger possesses the rare instinct of recognizing the setting for a good picture when he sees it, many of the views being truly artistic.” Truthfully, his work was competent overall, with many of the plates being more “snapshot” in nature although documentary images scattered throughout the volumes show better than average compositional qualities. From: PhotoSeed Archive

“Moonlight on the Riverway”: Ph.(ilippe) H. Bonnet: 1904-1977: American: born France: blue-toned silver bromide print? ca. 1930-40: 24.8 x 18.6 | 38.6 x 26.3 cm: As a younger man, Philippe H. Bonnet was a staff photographer for The Tech, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s undergraduate student newspaper. He is believed to have graduated from MIT in 1931 as listed in the Tech. In the early 1960’s, a newspaper said he was a well known Boston architect. He also later made a name for himself as a railroad photographer-especially of trolley cars- and made his own real photo post cards and stamped them individually as a “Ferroviagraph”. This scenic view of a river in Winter is from a series of landscape photographs believed to have been taken by him in the Middlesex Fells Reservation, a 2500 acre natural area located just north of Boston. A double-lined, hand-ruled frame in blue ink compliments the deep-blue effect achieved through the action of blue-toning. From: PhotoSeed Archive

“Baby’s Breath Growing in Wild”: unknown photographer: blue-toned gelatin silver print: ca. 1930-40: 12.5 x 10.5 | 13.2 x 11.4 | 23.8 x 31.9 cm: This delicate study of what are believed to be Baby’s Breath flowers (Gypsophilia, or Das Schleierkraut) is presented here in an album by an anonymous photographer (purchased from a seller in Greece) including a selection of pictorialist works featuring nicely mounted cityscape, mountain, and marine views, several of which show Frankfurt, Germany. From: PhotoSeed Archive

And in conclusion, a final cyanotype:

Detail: “Dorothy Tucker Mounting Photographs”: Charles Rollins Tucker: American: cyanotype: ca. 1903: 11.3 x 8.6 | 15.0 x 12.6 cm: Seated on a stool, Dorothy Tucker, (1899-1986) the young daughter of amateur photographer Charles Rollins Tucker, is shown using an E. & H.T. Anthony brand Print Mounter to mount a photograph on a work table. Possibly taken for one of the yearly amateur Kodak advertising contests, the work space shows a Kodak Brownie camera at right rear, loose photographs, an album and a jar of what is most likely “Daisy” mounting paste with a brush next to it. Gripping the top of the mounter, young Dorothy prepares to slide the mounter with its two rollers over a print seen just to the right of it. The initials “EA” for Edward Anthony, are engraved on the side of roller. The E. & H.T. Anthony firm was considered the largest manufacturer and distributor of photographic supplies in the United States during the 19th century. From: PhotoSeed Archive