Amateur-Kunst: 1891 Vienna Exhibition

Introduction: The 1891 Vienna International Photographic Exhibition

Organized, international exhibitions of so-called artistic photography had taken place many times around the world before the groundbreaking one known as the Internationale Ausstellung Künstlerischer Photographien in Wien 1891 (International Exhibition of Art Photographers) was organized by the Club of Amateur Photographers (Club der Amateur Photographen in Wien) in Vienna, Austria in 1891. Indeed, this very club, renamed the Vienna Camera Club in 1893, had hosted their first successful international exhibit in 1888. Even in the same year (1891) the Vienna exhibit was held, two noteworthy international exhibitions would be held in England: one in Liverpool, running from March to April that spring and another under the direction of the Glasgow & West of Scotland Amateur Photographic Association in September.

What made this exhibition held at Vienna’s Imperial and Royal Austrian Museum of Arts and Manufactures different and important in the context of promoting artistic photography to a larger worldwide audience? For that, a look at the structure of the Vienna club and the forces that created it are essential. 4000 photographs were entered from around the world for possible exhibit. The jury that ended up picking 600 examples for hanging came from a pool of mostly academic artists and a lone royal court photographer. Running from April 30 through May 31, 1891, the club later that year issued an elaborate portfolio in two separate editions consisting of large-plate photogravures commemorating their achievement-the plates of which are here presented in their entirety.

Vienna Camera Club Beginnings: Evolutionary Pictorialism

In his insightful essay on the founding of The Vienna Camera Club, contemporary author Manon Hübscher documents the fact that what we understand as pictorialism or the artistic photography movement was born by the groundwork of the club’s very establishment in the late 1880’s:

“Through the initiative of Carl Srna, Dr. Federico Mallmann, and Charles Scolik, the Club der Amateur Photographen in Wien was founded on March 31, 1887. This potent crucible is of particular interest because its history provides a synthesis of the circumstances, issues, and ideas that determined the evolution of Pictorialism.” 1.

Some of those circumstances, Hübscher writes, was the reality of:

“imperial Vienna, already in political decline owing to the failures of liberalism and the rise of nationalism, had become the symbol of a rich and diverse center for literature, music, other arts, and the sciences, a phenomenon that was often encouraged by the authorities.” 2.

And photography itself was not neglected- he writes:

“stimulated by rapid industrial expansion and the accompanying rise of a bourgeois class that had the wealth and resources to pursue such leisure activities, was also supported by political, military, and scientific circles, which had been quick to grasp its significance.” 3.

Distilling it further, Hübscher suggests Austrian pride came into play to elevate the importance Vienna Camera Club members felt was part of their agenda:

“The Club, guided perhaps as much by an elitist desire to assert Austria’s national spirit as to assert its own status as a global pioneer of art photography, staged two international exhibitions in Vienna, the first of which ran from September 15 to October 25, 1888, while the second was held in the spring of 1891.” 4.

Hübscher argues the 1891 exhibition itself was instrumental in establishing the Vienna Camera Club’s credibility to a larger audience:

“Organized with great pomp and ceremony by the Club der Amateur Photographen in Wien (Vienna Amateur Photographers’ Club) and dedicated to the medium’s artistic dimension, the International Exhibition of Photography held in Vienna in 1891 paved the way for the Club’s success, enabling its dazzling and almost immediate elevation to the status of a model.” 5.

Four months after the exhibit closed, an in-depth, ten-page article on it appeared in the September, 1891 issue of the Vienna Camera Club’s own journal, the Photographische Rundschau, under the direction of editor-in-chief Charles Scolik and club president Carl Srna. Hübscher includes the following observation made by club members in the article:

“Our plan for an exhibition has met with great acclaim in all national and foreign photographic circles; the recognition does us honor. People are finally beginning to take art photography seriously…This is the dawn of a new era…This exhibition has enabled the opening of a brilliant page in the history of photography.” 6.

Another contemporary writer and photographic historian, Weston Naef, weighs in on the importance of the 1891 Vienna exhibition:

“The significance of the exhibition was that it was the first international collection aimed at assembling the very best work from around the world without the prizes and awards that had come to be thought of as so undesirable at the Pall Mall Salon.” The organizers did much homework before advertising the competition and making their final choices. They exercised considerable foresight in being the first to include the younger generation who would actually make a mark on the aesthetic development of photography.” 7.

Naef concludes by saying the 1891 exhibitions impact would have a ripple effect, perhaps even influencing the birth of the major British photographic secession to follow it, The Linked Ring:

“The Vienna Salon was a catalyst vital to upgrading the standards that would be applied to local exhibitions. The following year, in 1892, The Linked Ring was formed.” 8.

Notes:

1. Manon Hübscher: The Vienna Camera Club-Catalyst and Crucible: in: Impressionist Camera: Pictorial Photography in Europe, 1888-1918 : Merrell Publishers : 2006 : p.125

2. Ibid

3. Ibid

4. Ibid: p. 126

5. Ibid: p. 125

6. Ibid: p. 126

7. The Collection of Alfred Stieglitz: Fifty Pioneers of Modern Photography: Weston J. Naef: The Metropolitan Museum of Art: 1978 : p. 22-24

8. Ibid: p. 24

Selling the 1891 Vienna Exhibit

Promotion and solicitation for the 1891 Vienna salon exhibit began showing up in the American photographic press late in the fall of 1890. In this respect, the Club der Amateur Photographen in Wien had no less a major patron than royalty itself: Austria’s Imperial and Royal Highness, the Archduchess Maria Theresia. An accomplished photographer who actively participated in the club’s exhibitions, Maria Theresia gave credibility to a club already well-funded by the deep pockets of its members, including future British Linked Ring member Baron Nathaniel von Rothschild. A fellow club member wrote of Rothschild’s largess:

“There should be a game and billiard room and a luxuriously furnished ladies’ salon.” 1.

Part of the promotion for the 1891 salon changed the accepted rules for exhibitions of the period. Weston Naef writes:

“The significance of the exhibition was that it was the first international collection aimed at assembling the very best work from around the world without the prizes and awards that had come to be thought of as so undesirable at the Pall Mall Salon. The organizers did much homework before advertising the competition and making their final choices. They exercised considerable foresight in being the first to include the younger generation who would actually make a mark on the aesthetic development of photography.” 2.

Rules in their entirety for the future exhibit were printed in Wilson’s Photographic Magazine for the issue of October 4, 1890:

“We have received further particulars of the Photographic Salon which is to be held in the Imperial Museum of Arts, Vienna, Austria, during May, 1891.

We present the circular as received, and would urge the fraternity to give it their special attention—because of the honor which attaches even to the admission of a photograph in the proposed Salon. The circular is as follows:

Club of Amateur Photographers in Vienna, I. Wallfischgasse 4. International Photographic Exhibition Salon in Vienna, under the patronage of Her Imperial and Royal Highness the Archduchess Maria Theresa, from April 30 to May 31, 1891.

The Club of Amateur Photographers in Vienna intends holding an International Photographic Exhibition at the Imperial and Royal Austrian Museum of Arts and Manufactures, which differs from the former Vienna Exhibition of 1888, by exhibiting only such photos as have artistic value.

The admission of pictures will be subjected to the decision of a competent jury of artists and photographers, which admission j is an honor and will be certified by special 1 diploma bearing the signature of the Patroness of the Exhibition, Her Imperial and Royal Highness the Archduchess Maria Theresa.

The jury has the privilege of recommending competitors for special good work for the Vermeil Maria Theresa Medal, which will be awarded by Her Imperial and Royal Highness. The number of these medals is not to exceed ten and must be awarded unanimously.

The approval of two-thirds of the jury is required for admission.

No scientific section can be admitted this time.

All photographs of artistic merit will be admitted, including: Landscapes, studies of flowers and of animals, genre pictures, portraits, etc., besides diapositives, lantern-slides, and stereoscopes. Every picture, not smaller than twelve centimeters by nine centimeters, must be mounted on a separate cardboard, with or without a frame. Suitable frames will be supplied by the Club free of charge. The subject and artist’s name must be on each picture. Pictures already exhibited in Vienna, 1888, cannot be sent in again.

Application must be made not later than the 15th of January, 1891, and exhibitors will kindly forward their photographs before the 1st of April 1891, to a London address, which will be made known in time, whence they will be forwarded and returned at the expense of the Club, and no further charges, as for wall-space, etc., will be incurred by exhibitors. The names of the jury will be published before the 1st of January, 1891. No exhibits will be allowed to be removed before the close of the exhibition. The jury will decide finally where the pictures are to be fixed.

The committee reserves the right of issuing further rules, if necessary. All communications to be addressed to the President of the Club, Carl Srna, Esq., VII. Stiftgasse 1, Vienna.” 3.

And in The American Amateur Photographer, an indirect solicitation for the exhibit by way of Archduchess Maria Theresia herself:

“The Secretary read a circular of the International Photographic Exhibition to be held in the salon in Vienna, Austria, under the patronage of her imperial and royal highness Archduchess Maria Theresia, from April 30 to May 31, 1891, under the management of the Vienna Amateur Photographers’ Club. Members of the society were invited to send exhibits. Miss C. W. Barnes showed a phototype picture of the Archduchess, who had applied for a photograph of Dr. Ehrmann of the Photographic Times, as she is much interested in photography. Thinking she might appreciate more highly a picture made by a lady amateur, Miss Barnes ventured to make a portrait photograph of the doctor in his own laboratory and studio. She arranged the lighting, made the exposure, and developed the plates, and was gratified to obtain a likeness which is very highly regarded by Dr. Ehrmann and his friends. As a member of the society she will thus convey to the Archduchess the kind of work American amateurs can produce. A copy of the photograph was shown, and appeared to be equal to any made by professional photographers.” 4.

In America, an announcement of the judges for the exhibit was made public in March, 1891:

“Jury of the Vienna International Exhibition, 1891.—Henry von Angeli, professor at the Imperial and Royal Academy of Arts, Vienna; John Benk, sculptor; Julius Berger, professor at the Imperial and Royal Academy of Arts, Vienna; K. Karger, professor at the Imperial and Royal School of Art-Industry, Vienna; Fritz Luckhardt, professor, imperial councilor, photographer to H. I. Majesty the Emperor; Augustus Schaeffer, director of the Imperial Picture Gallery, Vienna.” 5.

Soon followed by an editor at Wilson’s Photographic Magazine strongly recommending participation and follow-up for American exhibitions based on the lead of the Vienna club:

“Some of the ablest artists in Europe have readily consented to act as judges at the Vienna Photographic Salon, which gives this exhibition added value; it promises indeed to become the most important event of its kind in the history of photography. We would earnestly recommend the officers of our P. A. of A. to get all the information they can from the promoters of the Vienna Salon, and utilize the ideas toward the improvement of the photographic exhibition at the next convention.” 6.

And this like-minded exhortation for representation in the exhibit by Anthony’s Photographic Bulletin, printed in late January, 1891:

“It would seem from indications thus far, that this country will be well represented at the forthcoming exhibition in Vienna. It is advised that prints be sent unframed, but mounted, and each print larger than 3 1/4 x 4 1/4 must be mounted separately. Exhibits may be sent to Mr. C. F. Eckhardt, 32 Aldermanbury, London, E. C., or to the Committee of the Vienna International Exhibition, at the Imperial and Royal Museum of Arts and Manufactures, Vienna. Applications for admission must be in Vienna by February 1st, addressed to Carl Srna, Esq., Club of Amateur Photographers of Vienna, Wallfischgasse 4, Vienna, Austria. The New York Camera Club expect to have a good representation, and it is to be hoped that other clubs will fall into line at once.” 7.

However, those subscribing to the American Amateur Photographer were directed to send entries to the exhibit directly to Alfred Stieglitz for forwarding to Vienna:

Vienna International Photographic Exhibition —

“An exhibition is to be held next spring, April 30 to May 31, 1891, under the patronage of Archduchess Maria Theresia. Photographs for the exhibition (which it is said will be very fine) should be sent before February 18, 1891, to Mr. Alfred Stieglitz, 14 East 60th Street, New York.” 8.

Notes:

1. Footnote #34: in the essay: Phases in the History of Pictorialism: Monika Faber: Heinrich Kühn: The Perfect Photograph: Hatje Cantz Verlag: Ostfildern Germany: 2010: p. 29

2. The Collection of Alfred Stieglitz: Fifty Pioneers of Modern Photography: Weston J. Naef: The Metropolitan Museum of Art: 1978 : pp. 23-24

3. The World’s Photography Focussed: in: Wilson’s Photographic Magazine: Edited by Edward L. Wilson: Vol. XXVII: October 4, 1890: pp. 604-605

4. Society News: The American Amateur Photographer: Brunswick, ME: The American Photographic Publishing Company: Volume II: December, 1890: p. 479

5. American Journal of Photography: Edited by Julius F. Sachse: Philadelphia: Thomas H. McCollin & Company: March, 1891: p. 124

6. The World’s Photography Focussed: in: Wilson’s Photographic Magazine: Edited by Edward L. Wilson: Vol. XXVII: December 20, 1890: p. 753

7. Editorial Notes: in: Anthony’s Photographic Bulletin: New York: E. & H. T. Anthony & Co.: Volume XXII: January 24, 1891: p. 36

8. The American Amateur Photographer: Volume III: Boston: The American Photographic Publishing Company: New York, N.Y. : January, 1891: p. 34

Epilogue: Commentary on the Vienna Exhibition

In England, while the exhibit was still in progress, an unknown review published in Vienna and translated and reprinted in London’s Photographic News weekly of May 15, 1891, gives an overview on the differences of the “new” and “old” photography with emphasis on English photographers at the exhibit:

“Before mentioning the individuals’ work we must call attention to the artistic excellence of the English photographs, which are undoubtedly the best, both as regards figure studies and landscapes. Two schools of photography are represented, the “old” and the “new” or impressionist school. In the former the desired result is attained by attention to detail; in the latter the pictures are worked so as to get an artistic and picturesque effect- just the same difference as is to be found in the paintings of today and those of some years ago. Some of the new school photographers even work with a pinhole camera (without objective), as Alfred Maskell; others, like Lyonel Clark, touch up their pictures to such a degree that they appear half paintings and half photographs. Foremost amongst the Impressionists is George Davison, and it must be confessed that both his landscape and figure pictures make a truly artistic impression. When they are compared with those of J. Gale, who works in the spirit of the old school, one can only say that all roads lead to Rome. The artistic value of the photography of Harry Tolley, Lyddell Sawyer and H.P. Robinson, is world renowned.’ Henry Stevens also received a mention.” 1.

While in America, news arrived more slowly, with commentary in the photographic press appearing several months after the show closed, including the number of American photographers accepted for the exhibition. In June, a list of American photographers accepted for the salon appeared, although the figures cited by Anthony’s Photographic Bulletin were inaccurate (there were actually 600 photographs accepted by 176 individual photographers):

“In the Vienna International Photographic Exhibition, the following American exhibitors have had their pictures accepted: H. McMichael, of Buffalo; John Dumont, of Rochester; George A. Nelson, of Lowell; Alfred Stieglitz, and J. L. Breese, of New York; Mrs. Grey Bartlett, of Chicago; John G. Bullock and G. B Wood, of Philadelphia; Miss Mary Martin and Henry B. Reid. Out of six hundred exhibits offered four hundred and seventy were rejected.” 2.

The readership of The American Amateur Photographer learned more in-depth facts, figures and opinions of the editors about American contributions to the Vienna exhibit:

Artistic Photography at Vienna

“THE new idea carried out at Vienna by which the hanging committee should act as judges in advance, and throw out photographs that did not possess some special art merit, has resulted somewhat singularly as regards the American exhibits. The management, we believe, agreed to pay the expenses of transportation both ways, but reserved the right to reject any pictures they saw fit. Men high in art were selected as judges. The report comes that out of 40 American exhibitors contributing 350 photographs, 30 were thrown out with their work, and but 25 photographs of the 10 accepted, were hung, as follows: Exhibitors from New York: James L. Breese, 2; Alfred Stieglitz, 5; Miss Mary Martin, 1; Harry Reid, 1. From Rochester, N. Y.: John E. Dumout, 6. From Philadelphia, Pa. : John G. Bullock, 2; George B. Wood, 5. From Chicago: Mrs. N. Gray Bartlett, 1. From Buffalo, N. Y.: H. McMichael, 1. From Lowell, Mass.: George A. Nelson, 1. Among Mrs. Bartlett’s pictures was “At the Spring,” illustrated in our June number.”

With the exception of one exhibitor from Philadelphia, we should judge from the above named awards that portrait and composition group pictures took preference over any others. None but the highest class of artistic work was accepted. We hear three duplicates of each picture that was hung are wanted for permanent preservation in two or three of the oldest galleries. Of all the foreign exhibitors the English photographers took the lead in point of numbers. Several pictures by Mr. G. Davison, of the London Camera Club, were accepted as well as others by Robinson and the leading English amateurs.

We sympathize with those of our American brethren who were not honored, believing that art tastes differ in different countries, and that while their work may not be justly appreciated abroad it will be at home. We must congratulate the successful ones that the art merit of their work corresponded with the views of the judges. Most all have been prize winners here, and it is good to know that American judges are not. after all, far out of the way.” 3.

Also, in the same month, the comments of an American critic on the efforts of female photographers in the exhibit, (although Miss Barnes and Mrs. Lounsbery are absent from the list received by the American Amateur Photographer) including the archduchess, appear:

“At the International Photographic Exhibition, lately opened at Vienna by the Archduchess Maria Theresa, are specimens of excellent work from many prominent feminine photographers in America and nearly every European state. The Princess of Wales sent excellent examples of her skill in picture making; the archduchess herself contributed bits of her best work; while Miss Barnes and Mrs. Lounsbery, from America, were represented by well-hung portraits, groups, landscapes, and interiors.” 4.

Notes:

1. The Vienna Camera Club: in: The Linked Ring – The Secession in Photography In Britain, 1892-1910 : Margaret F. Harker: A Royal Photographic Society Publication: 1979: p. 66

2. Editorial Notes: in: Anthony’s Photographic Bulletin: Volume XXII: June 27, 1891: p. 355

3. The American Amateur Photographer: Volume III: Boston: The American Photographic Publishing Company: New York, N.Y. : July, 1891: pp. 268-269

4. The Illustrated American: Edited by Mary L. Bisland: The Illustrated American Publishing Co. Bible House, Astor Place: New York, N.Y.: Volume VII- July 4, 1891 p. 326

Amateur-Kunst: The Vienna Exhibition Photogravure Portfolio

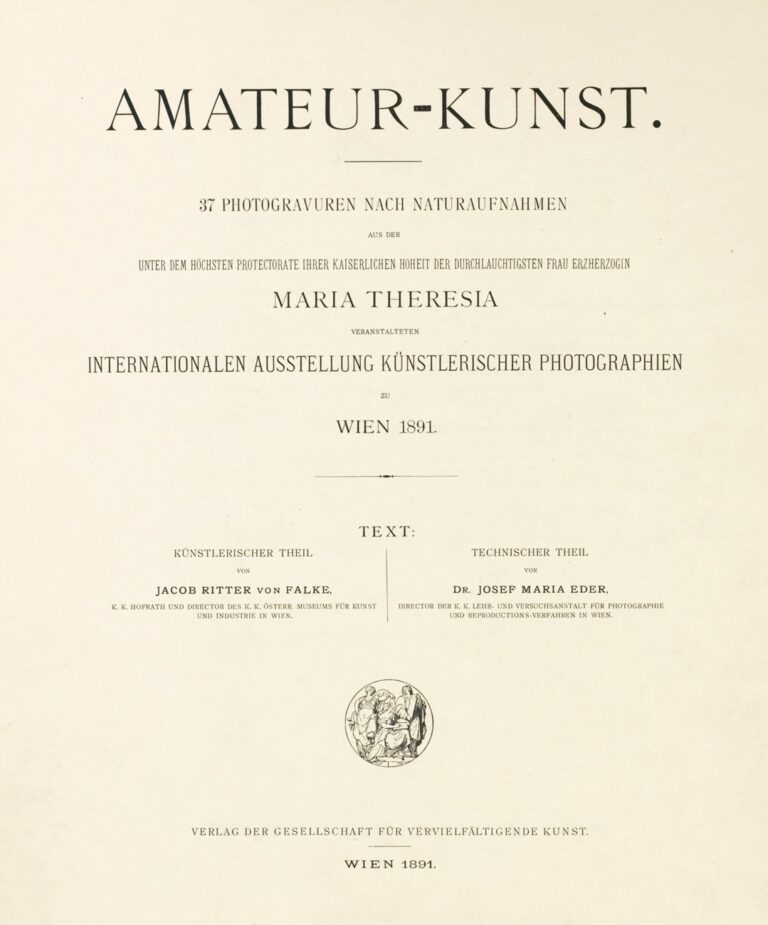

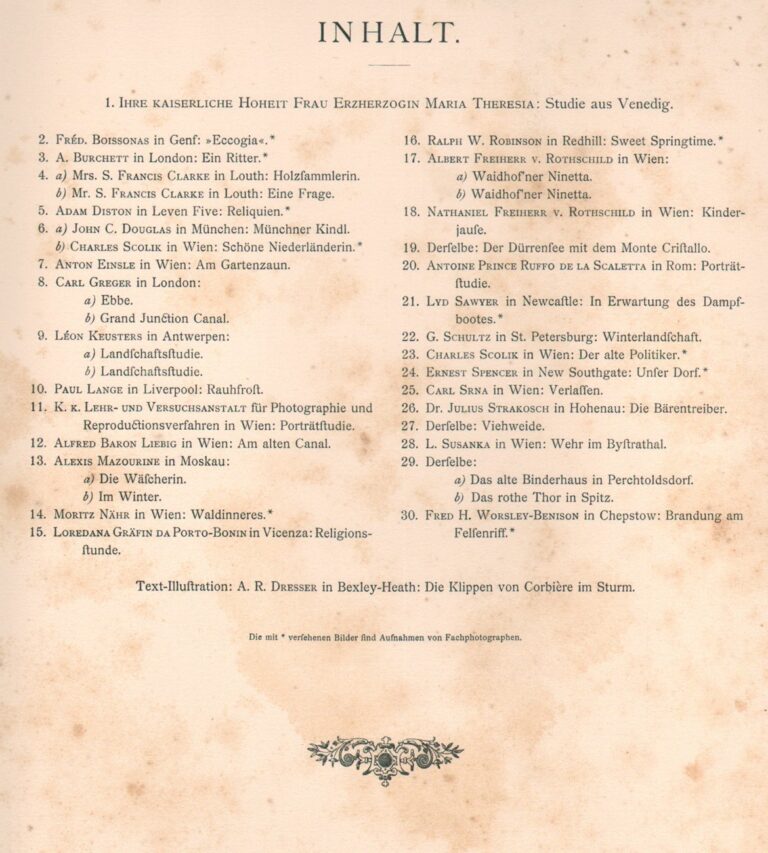

Late in 1891, on the twentieth year of its founding, the Vienna publishing house Gesellschaft für Vervielfältigende Kunst (Society for Art Duplication) issued two portfolios of large-plate photogravures featuring 37 photographs from the 1891 exhibition titled Amateur-Kunst (Amateur Art): 37 Photogravuren Nach Naturaufnahmen (37 photo engravings after nature photographs) The portfolios were issued in small limited editions (perhaps no more than several hundred examples in total as only several examples survive worldwide in institutional collections). A deluxe edition on Japanese paper was priced at 60 German Marks and a regular edition printed on Chinese paper (Chine-collé) was priced at 40 Marks. The 30 photographic plates (7 of the plates being diptychs) and letterpress for each were issued loose for both portfolios in a gray cloth over boards, three-point folder.

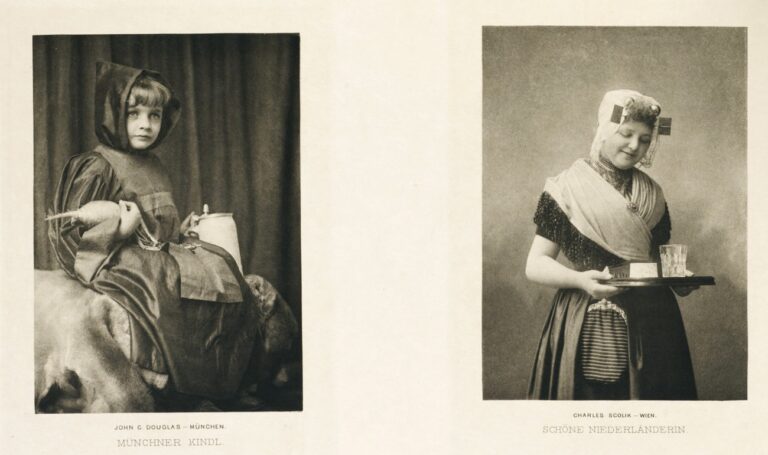

The letterpress includes a separate title page, contents (Inhalt) page with listing of photographic plates, and two long-form essays. The first, an artistic one (Künstlerischer Theil) was by Jacob Ritter von Falke, (Jacob von Falke) the Director of the Imperial Austrian Museum for Art and Industry in Vienna (K.K. Hofrath und Director des K.K. Österr. Museums Für Kunst und Industrie in Wien) The second essay was a technical one , (Technischer Theil) authored by Dr. Josef Maria Eder (1855-1944). An Austrian chemist, Eder was a prolific writer and photo-historian who later authored the first modern history of photography in 1905 (Geschichte der Photographie: first posthumous translation of the work was History of Photography by Edward Epstean in 1945) At the time of the portfolio’s publication, Eder was the Director of the Imperial and Royal Graphic Arts Institute in Vienna. (Director Der K.K. Lehr- und Versuchsanstalt Für Photographie und Reproductions-Verfahren In Wien)

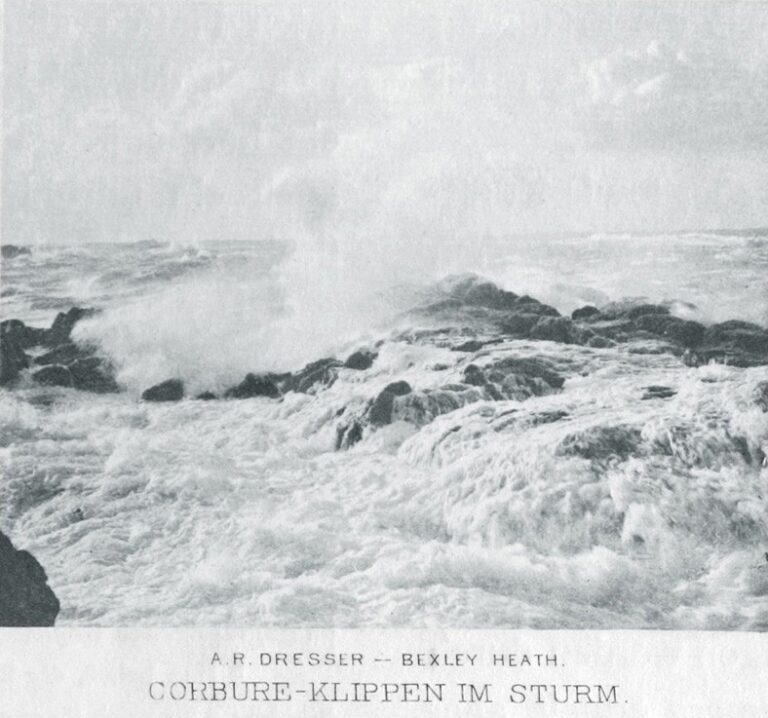

All of the copper plates for the portfolios were prepared and etched by Richard Paulussen, an expatriate Englishman working independently in Vienna who had an active relationship with the Gesellschaft für Vervielfältigende Kunst. The plates themselves, under Paulussen’s supervision, were printed for this publishing house by the Kaiserlich-Königlichen Hof- Und Staatsdruckerei in Wien-(Vienna’s Imperial and Royal state printers). Nine of the photographs listed on the contents page of the portfolio additionally bear an asterisk: Die mit * versehenen Bilder find Aufnahmen von Fachphotographen, indicating it was taken by a professional photographer. A separate small photogravure by English photographer Arthur R. Dresser is additionally included on the introductory final letterpress page of the portfolio. Comparative measurements of plate impressions from the two different portfolios (Japan and Chine-collé) reveal discrepancies in measurements for some of the plates-indicating the possibility Richard Paulussen prepared two sets of copper plates for their printing. Measurements for this online presentation are for the Japan plate edition.

Criticism of the Portfolio in the Vienna Camera Club's journal

In keeping with the independent spirit that made the Vienna Camera Club such an important voice for its’ time, the editors of the club’s journal, the Photographische Rundschau, printed a lengthy essay on the portfolio, with commentary for each plate, in their December, 1891 issue. Revealingly, the editors take exception to the very title of the work: Amateur-Kunst (Amateur Art). They state it is misleading as the subject matter for the portfolio is photographic art. To confuse matters more, they then point out a third of the photographic plates for the portfolio were done by professional photographers! Their original commentary follows:

“Wenn wir nun auch etwas zu tadeln suchen wollten, so böte vielleicht der Titel des Albums hierzu geeigneten Anlass. Mit dem Worte „Amateurkunst” können wir uns ganz und gar nicht befreunden. Ersteus weiss man hier nicht, dass man es mit photographischen Leistungen zu Thun hat, denn Amateurs giebt es auf allen Gebieten der Kunst. Dagegen giebt es kein Gebiet der Kunst, das ausschliesslich von Amateurs gepflegt würde, also kann von keiner „Amateurkunst” die Rede sein. Man könnte vielleicht glauben, es sei Amateur-Photographen-Kunst gemeint, allein von den Autoren der oben angeführten Bilder sind zufällig gut ein Dritttheil Berufsphotographen! Wie erklärt Graf Oerindur diesen Zwiespalt der Natur?” 1.

1. Photographische Rundschau: Centralblatt fur Amateurphotographie: Edited by Charles Scolik: Volume IV: December, 1891: Published by Verlag Wilhelm Knapp: Halle a. S.: p. 443

Amateur-Kunst : Künstlerischer Theil : Jacob Ritter von Falke

PhotoSeed wishes to thank Frauke Fischer for transcribing author Jacob von Falke’s original essay on his artistic observations of the 1891 Vienna exhibit from the Old German. Due to dialectical variances in the original, the complete essay is posted as part of our online exhibit for purposes of further scholarly investigative clarification.

Amateur-Kunst : Künstlerischer Theil : Jacob Ritter von Falke

“The well known Chinese ability to paint their pictures both close up & far away was so real to see for human eyes. That was the first step for a camera. For the first time you could identify the bullet flying and the movements of the waves from the beginning to the end. The photographic machine not only saw that motion it also brought it to a standstill. Photography accomplished herewith the impossible to reality. It taught us to see things a human eye never could comprehend. The photo showed us every leaf of the tree, every blade of grass, the stars of the universe. In other words, as if God counted every hair on our head. In all, it was pretty amazing from the artistic photographic aspect- it was really a Chinese way of creativity. One could say photography not only showed all the movement but also brought beauty into light. She wasn’t happy just to show the Sun, Moon and Stars and everything on Earth alive and dead, but in the way of art and at the end result it wasn’t quite the Chinese art.

Out of the artistic view of the photographer became the time of the Impressionist not only to be on the side of the painter, but also the photo to show the real and unreal story so the human eye can see and understand the expressions. We see the closeness close and the faraway fading away. We can see the air playing a role, the shadow and the light coming together. The photo brings everything to light, showing as it really is especially from the eyes of the artist.

This new theory of photography in an artistic way resulted in this year’s exciting show of amateur photographers clubs in Austria’s museum because of the interesting new way of presentation. The new way was just there without having it on their mind.

The 2nd International show was all about the artistic side. Only those were shown that seemed artistic, colorful and beautiful. Because of this a new jury of painters, artists and sculptors was born, for they admired the special ways of the photographers and did not judge the technical side but only the artistic side as the important one. Photography had to prove in itself as art like the painters use of paint, brush & pencil. Everything came together. Out of 4000 photographs only 600 were chosen for this exhibit which were pleasing to the artistic palette. Maybe this would give clear understanding to the photographic arts the popularity it needed. Though it gave pleasure to the artistic eye, the feeling side was brought into light. Of the 600 photographs mostly were scenery and mostly English. The second part genre photos and the third were portraits. The historic and heroic pictures of this time could not be done by itself. To wait for the right moment to take a dramatic picture, like a meeting for government and voting was too time consuming. An Englishman, who toured with a lion tamer, was waiting patiently to take photos at the specific moment when the trainer put his head into the lion’s mouth. These precious moments needed help of guidance when to take an action shot.

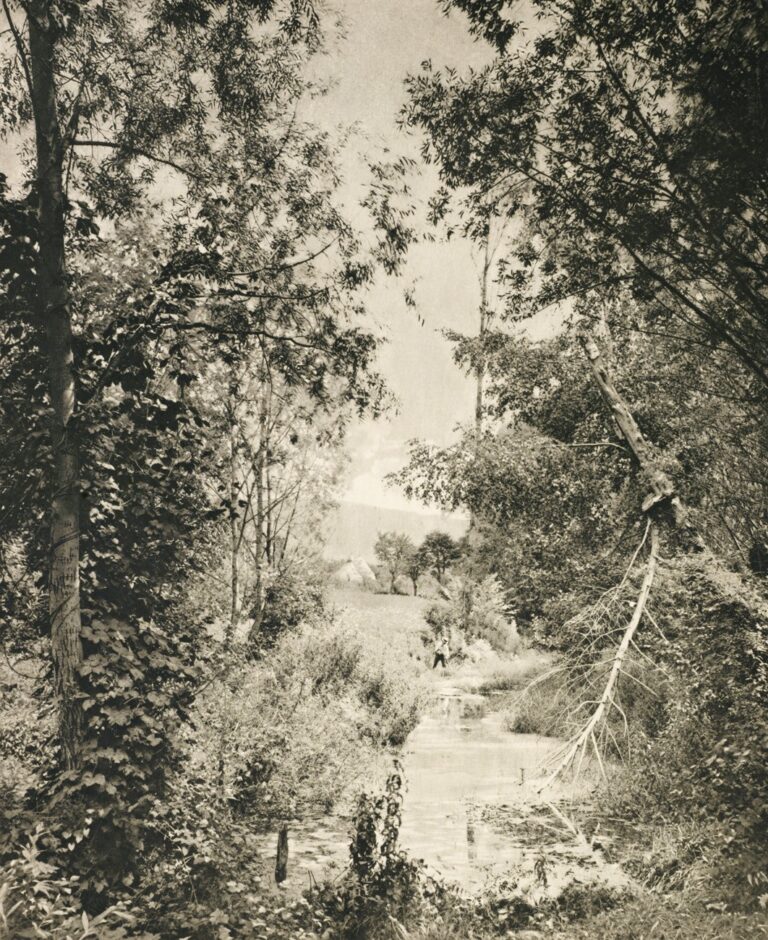

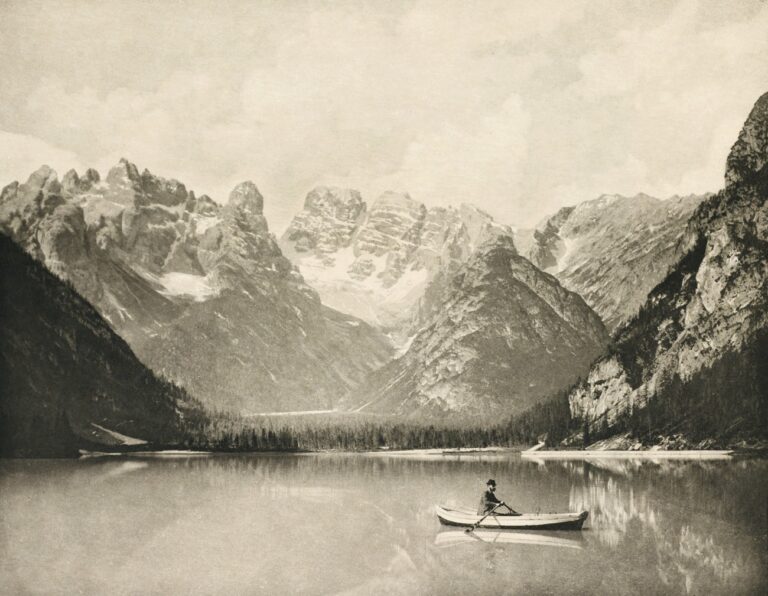

Amateur photographers took pictures of nature scenery but only photographers, men and women alike, with an eye and feeling for photography understood to snap pictures of scenery in all its glory and intimacy.

Among the special guests at the art show we found perfectionism in itself, her Royal Majesty Maria Theresia, Princess of Wales, his Majesty Ferdinand Von Toscana, Prince Heinrich Von Bourbon and the Earl Von Bardi who were judged by the Prince Heinrich Lichtenstein, the Earls Hans Wilczek, Karl Esterhàzy, Karl Brandis, Karl Chotek and also three members of the house of Rothschild, the Barons Albert and Nathaniel from Vienna and the Baroness Adolphe Rothschild from Paris, the Prince Antonio Russo, the Baroness Loredana da Porto and more.

Many of the important people, not only in name, took part in the art show and came from far away like France, America, Italy, Russia, but the most were from England. You could call it the English show.

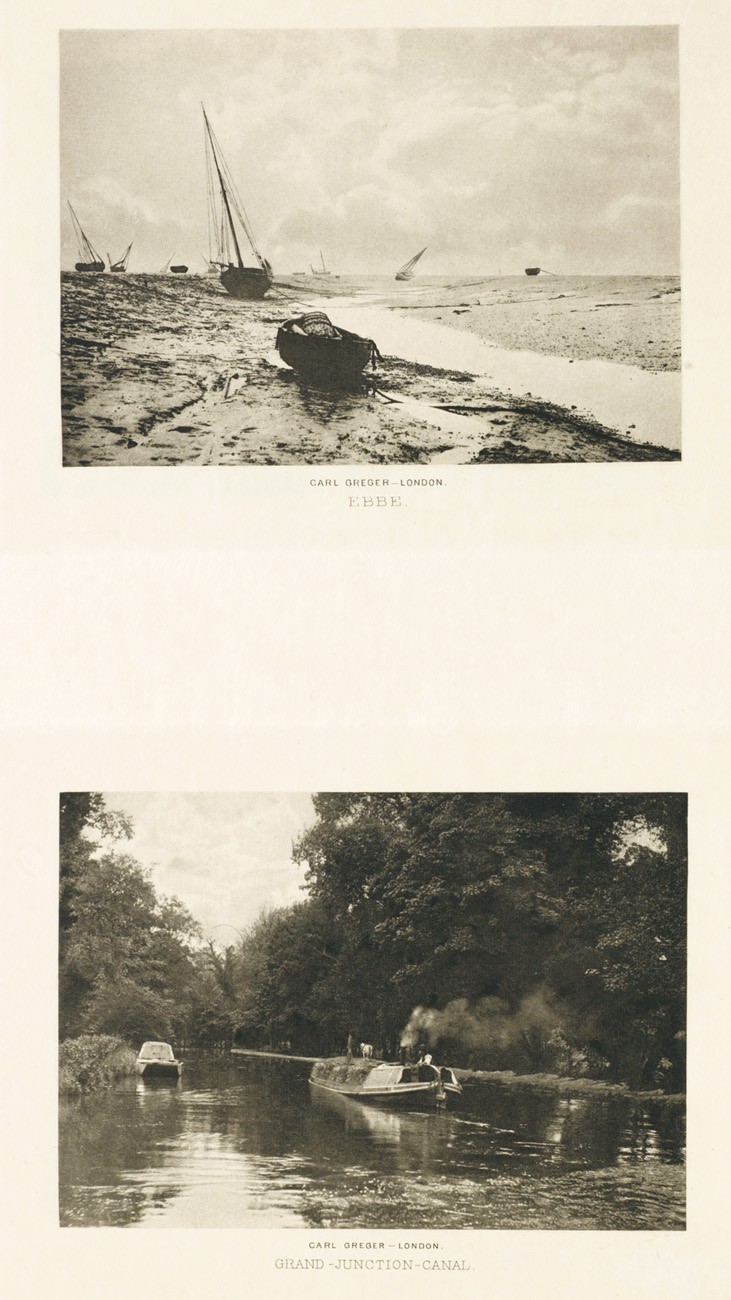

The best of the nature scenery was sent from England and the English amateur photographers, who began at the time of the impressionist were plentiful. There were George Davison, from London, J. Gale from London, Pattison Gibson from Hexham, A. Horsley Hinton from London, Paul Lange from Liverpool, H.P. Robinson from Tunbridge Wells, Fred Thurston from Lutton, Fred H. Worsley-Benison from Chepstow, Carl Greger from London, Ernest Spencer from New Southgate, R.W. Robinson from Redhill and many more. Especially goes recognition to W. Clement Williams from Halifax who took pictures of the sea world.

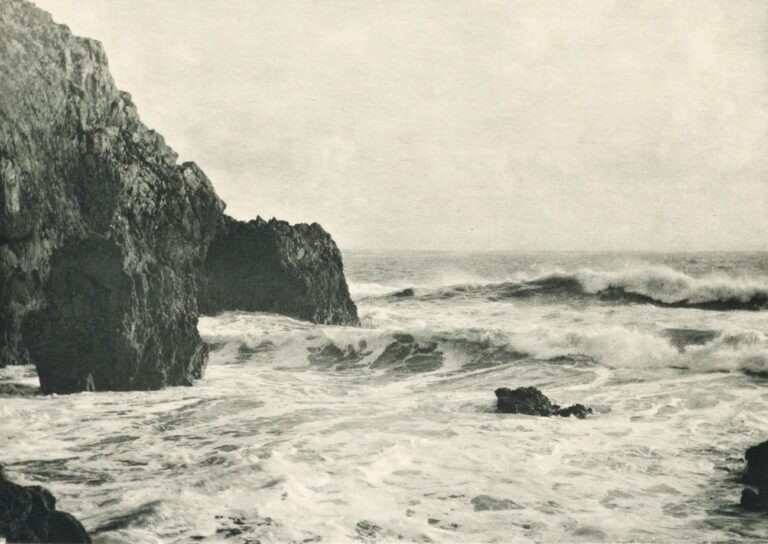

What all of them had in common of schooling and guidance was to paint real nature and beauty with the naked eyes to express the nearness and distance fading away, to create the moments of moving clouds, shadows, sunlight and moonlight, the difference of morning and evening, fog or clear sky for us to recognize. It is astonishing how clear the colors and mixing with others were transformed for us to see. For example a leaf or a foggy morning by Thurston, damp foggy woods- was a picture in itself, without the technical glimpse. Also the gorgeous blue tone painted seas from Williams with the fast fleeting storm clouds and the flickering lightening on the waves. There are three paintings- Storm Clouds, Moonlight on the Sea and the Silent Night were the most beautiful paintings of the art show presented where the photography captured the brilliance of a painting for the first time. Photography took & showed the moment with every detail, the movement of the waves, the blinking lights so detailed that one thought you stood before a painting. The sea was most likely to become the hobby model of the English impressionists, even in their most wild and calmest moments. The incoming tide which is slowly moving and playfully reaches the bank, the waves of water hitting the rocks are here captured in the moment of taking the picture and the feeling of the artist.

Other amateur photographers love to transform the serenity of countryside into pictures. They love the scenery of parks with its trees hanging low over the water, the cornfields, the hills of the countryside, the quaint little villages by the forest and the lovely countryside in itself. The ever changing time of the day, from the beginning of the mornings to the darkened evenings and nights. The picture from Thurston “Der Weidenwechsel”, where a herd of sheep is coming toward us from a walkway out of the forest or the two other pictures: “Die Eindringlinge” and “Unser Dorf”. A masterpiece from another side from this same artist was “Rauhfrost”-a picture of a frost covered forest.

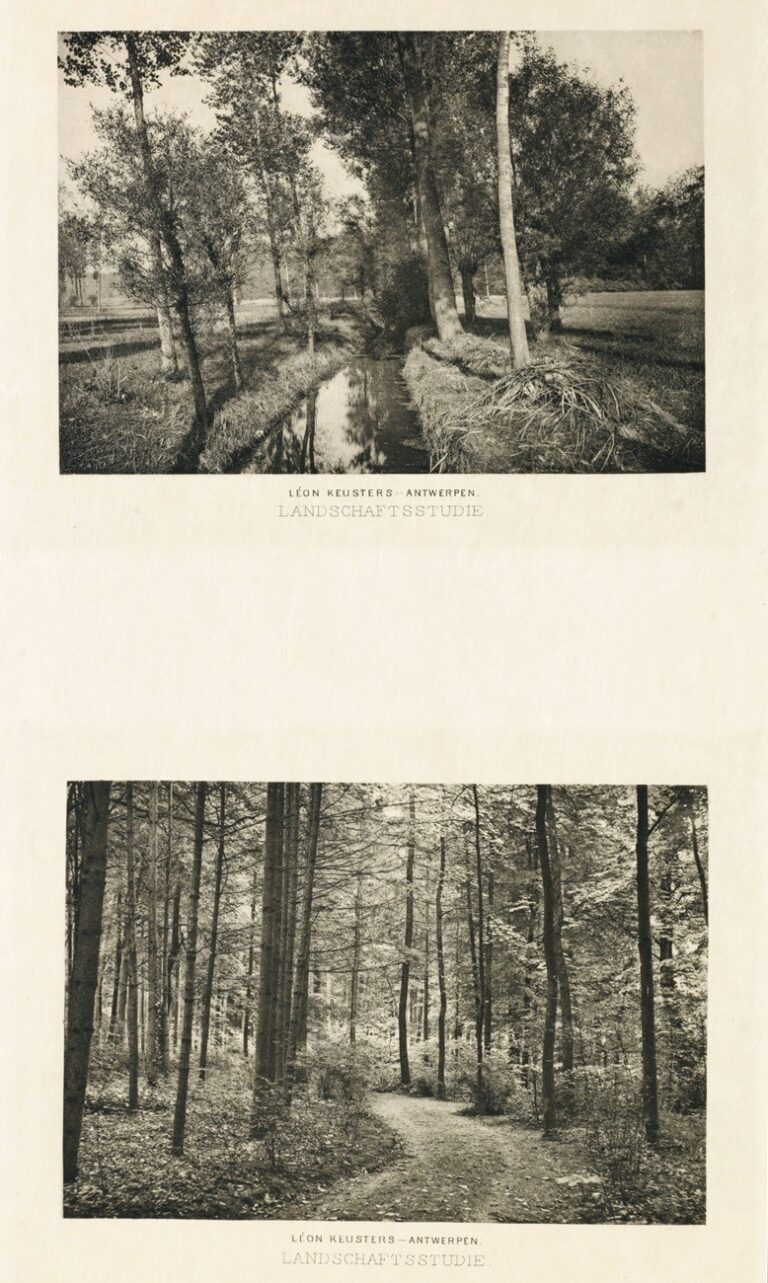

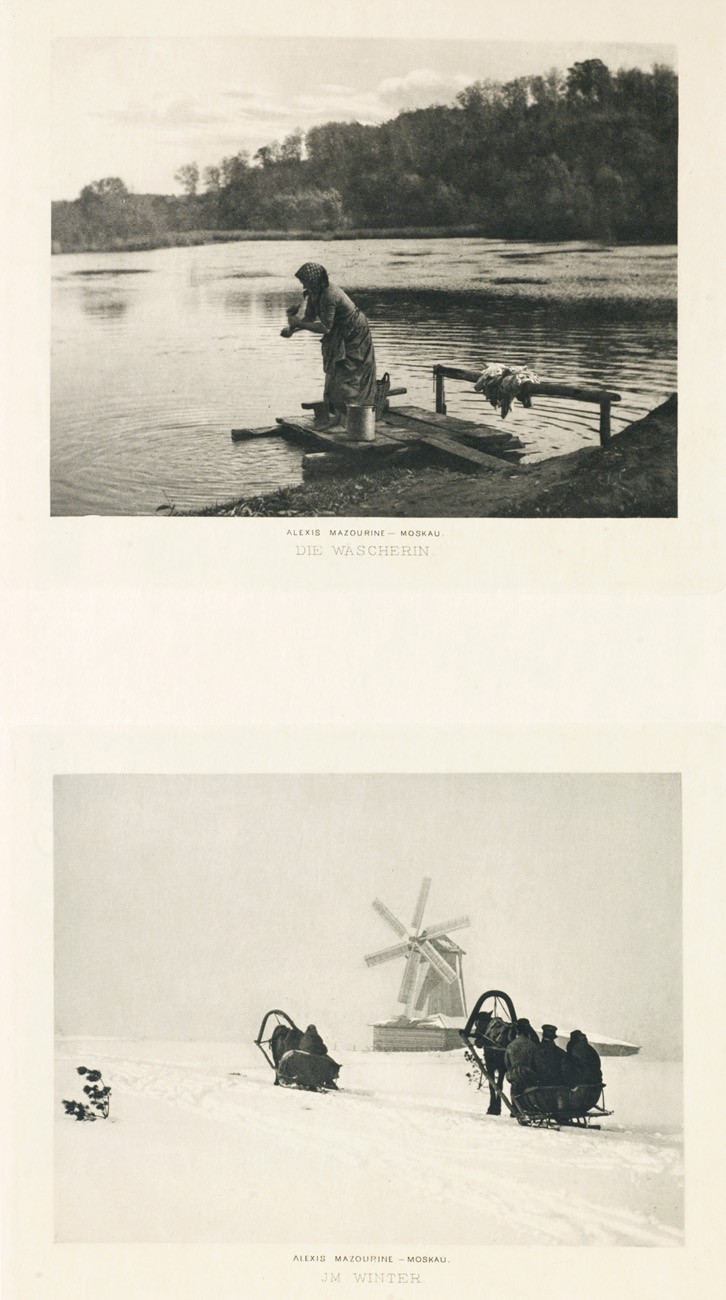

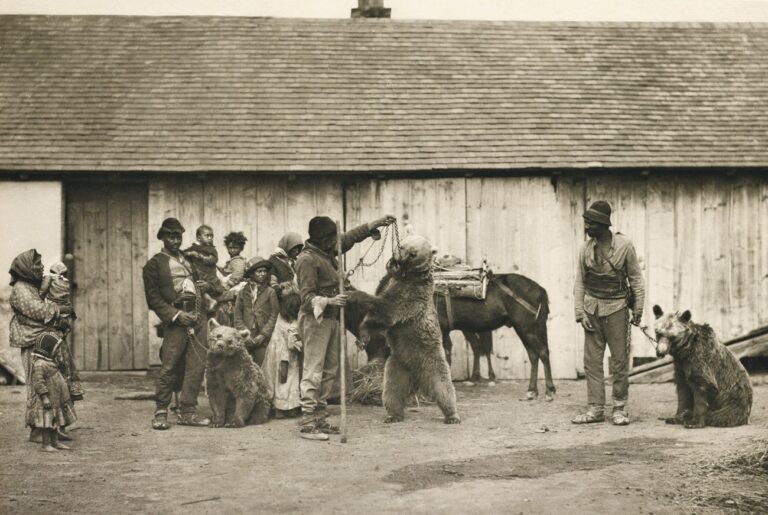

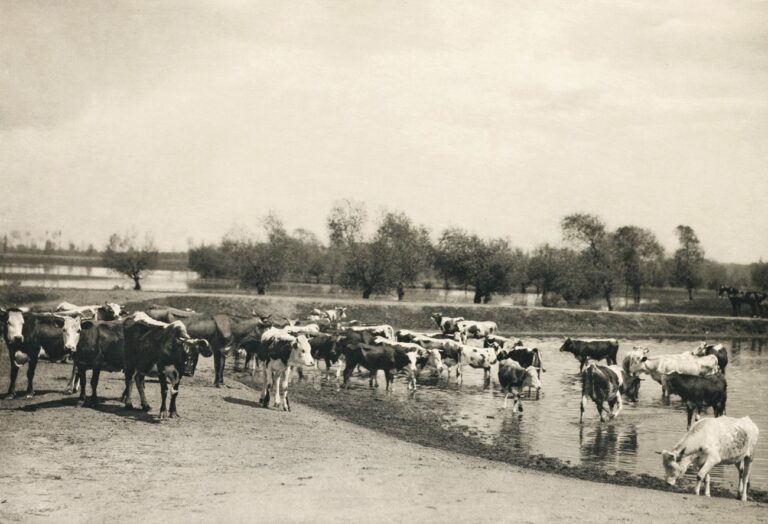

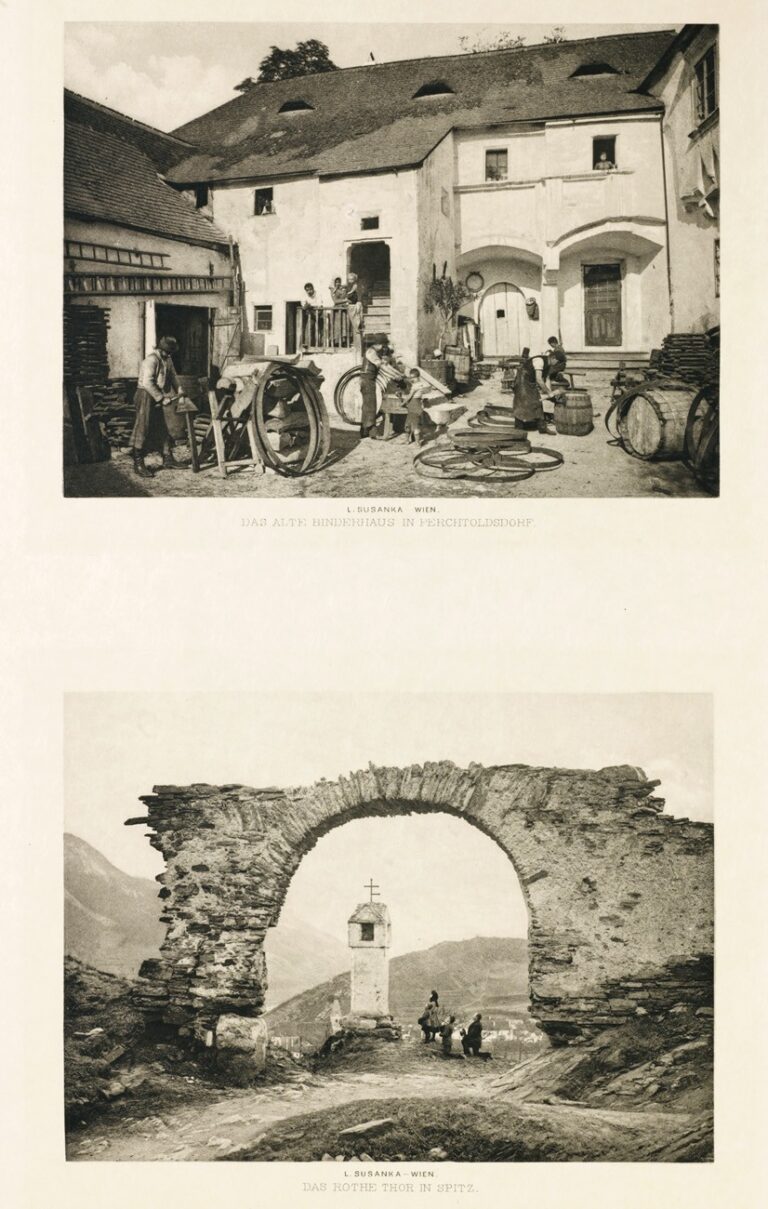

In those photos the English amateurs are tops, but many are competing against those where sharpness is progress. The beach pictures from Dreesen of Flensburg were excellent, he was bringing life into his harbor pictures, the sea with all the movements and stillness was fantastically portrayed. But here goes the nature scenery or marine already over into the genre picture, and in this second phase the amateur photographers received recognition and praise. One could find many things at the art show that brought out the significance of nature: farmers in the fields, cows and shepherds on the grasslands, small towns and fishing scenes, groups of children sitting together, scenes of soldiers and so many other things needed for the moment picture showing us the true countryside other than the opposite side of a posed one. Just to mention a few names of still photography are Anton Einsle, Alfred Baron Liebig, Moritz Nähr, Carl Srna, L. Susanka of Vienna, G. Schultz of St. Petersburg, Alexis Mazourine of Moscow, Léon Keusters of Antwerp, Dr. Julius Strakosch of Hohenau and Fréderic Boissonas of Switzerland.

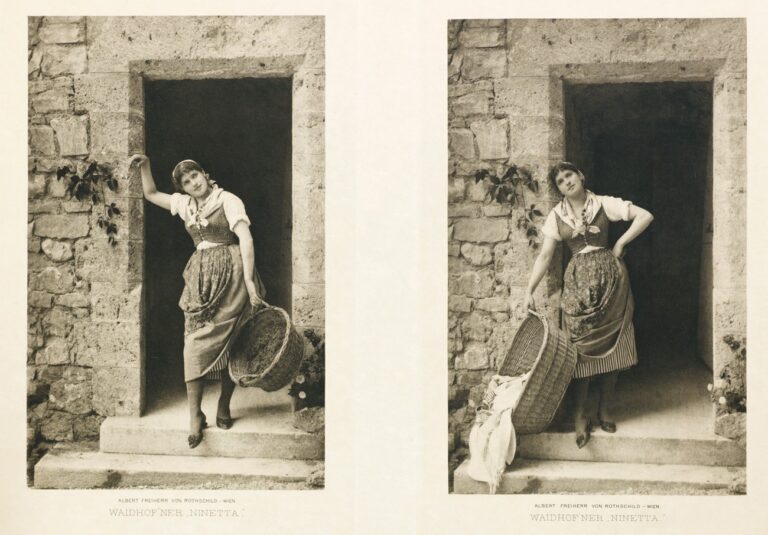

The posed genre photo perhaps could have its charm like the two photos from Baron Albert Von Rothschild. Because of the posed photographs and the unwilling intrusion it was more difficult for the genre photographers or the ones where the countryside and posed side were brought harmoniously together. It was most difficult in posing the figures and not let the intention be known in the model or group in order to bring out the natural state and true beauty and the shadows & light combined. Therefore these were more like Dutch genre photos, not only from the photographic side but the real artistic side. Here the jury decided to take 18 photos from Countess Loredana da Porto for the viewing of the genre photographic side.

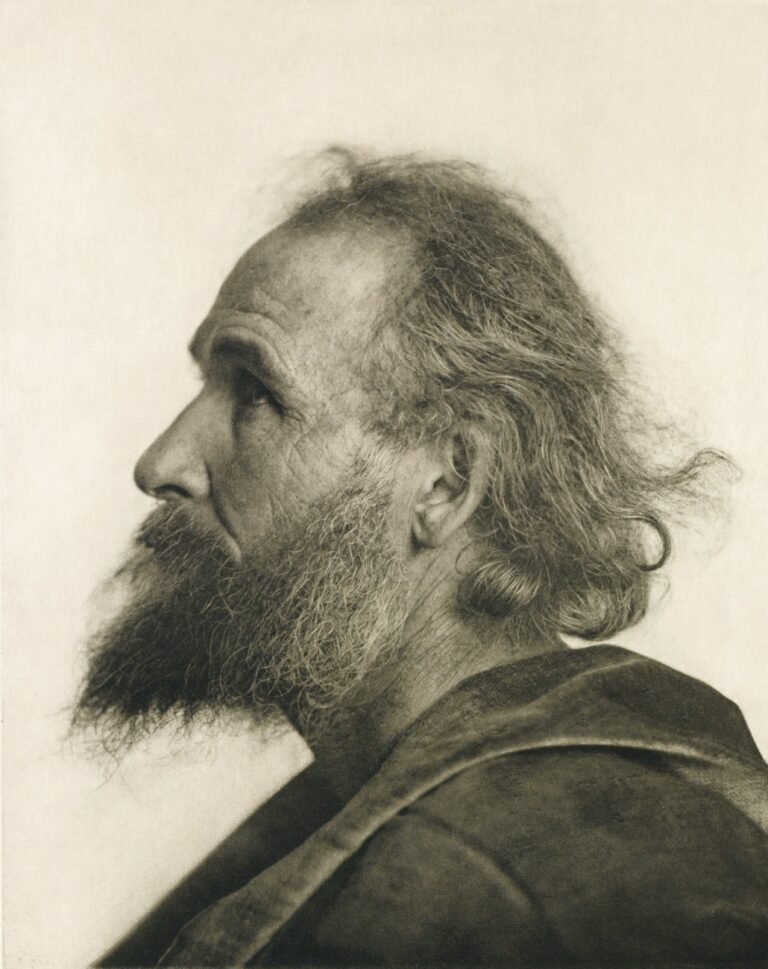

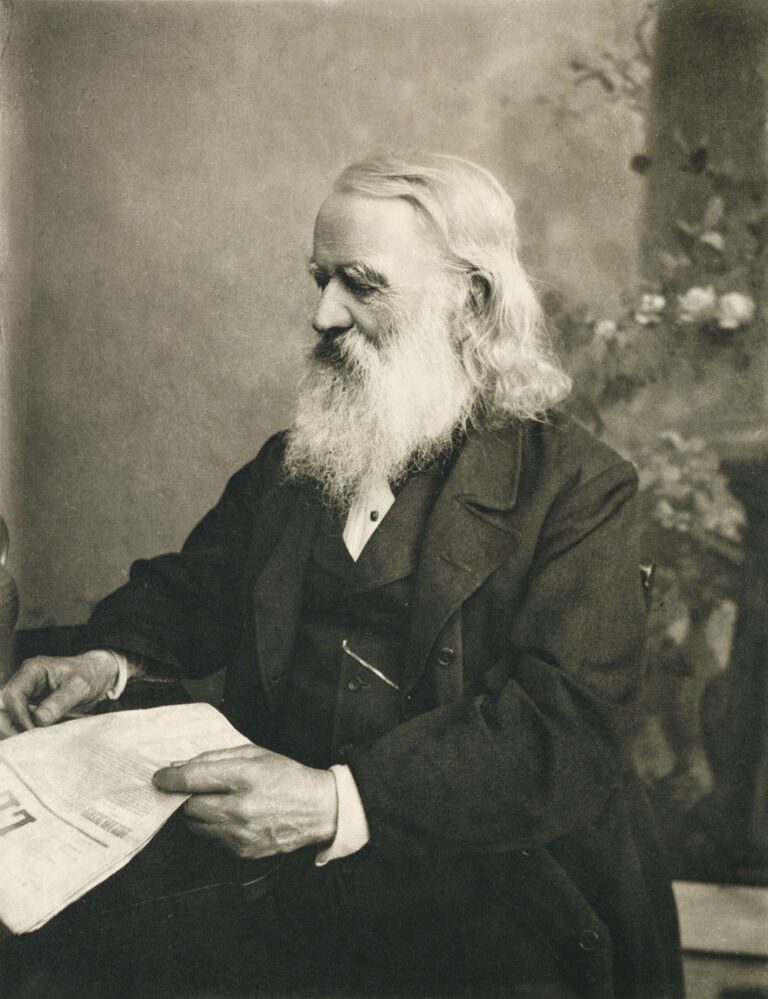

It was much more difficult for the portrait way. The amateurs here were rivals with the occupational photographers who showed their best of the best, also on the artistic side, the worst. The photography here was to become art, the portrait into a painting. It should describe the original without triviality in the plain and creative style of the masters. Many tried to reach this understanding and sometimes attained this knowledge, sometimes only as a study and also as a real portrait. Like Rembrandt portraits, the images from Ribera or Caravaggio let us think of portrait studies by Prince Antonio Ruffo. There was also some French influence in the portraits by Edgar de Saint-Senoch of Paris whose excellent bust of Prince Heinrich of Lichtenstein was perfection as a picture as well as a portrait of Professor Stuart Blackie by R. Faulkner of London. We also would like to mention a woman’s portrait in profile by Mrs. Susan Hodgson and two photos by special photographers: “A Knight” by Arthur Burchett and the “Old Politician” by Charles Scolik.

Truthfully we could mention many more, not only for their portraits and figures, but genre pictures and landscapes could we write about in the catalog. Everything was very good shown at the art show. It gave a lot of pleasure to the people who were knowledgeable in the movements of photography. In the interest of this versatile art show and everything it portrayed it has been a delightful idea for the Friends of Photography to put together this album to remember it by.”