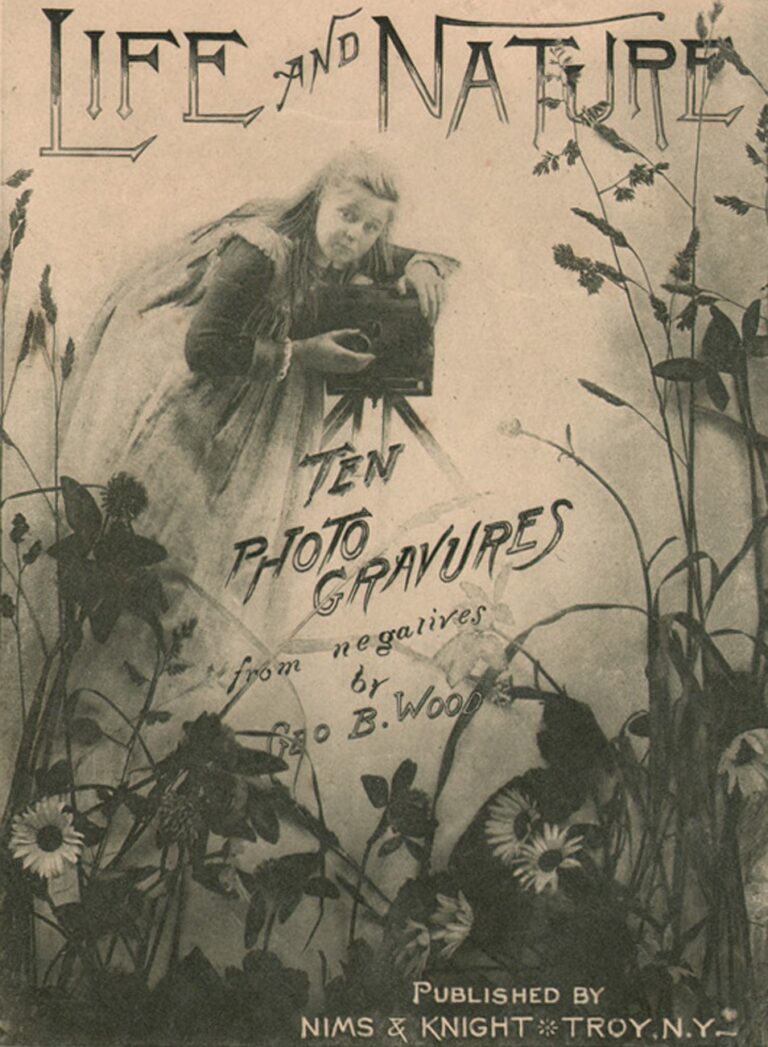

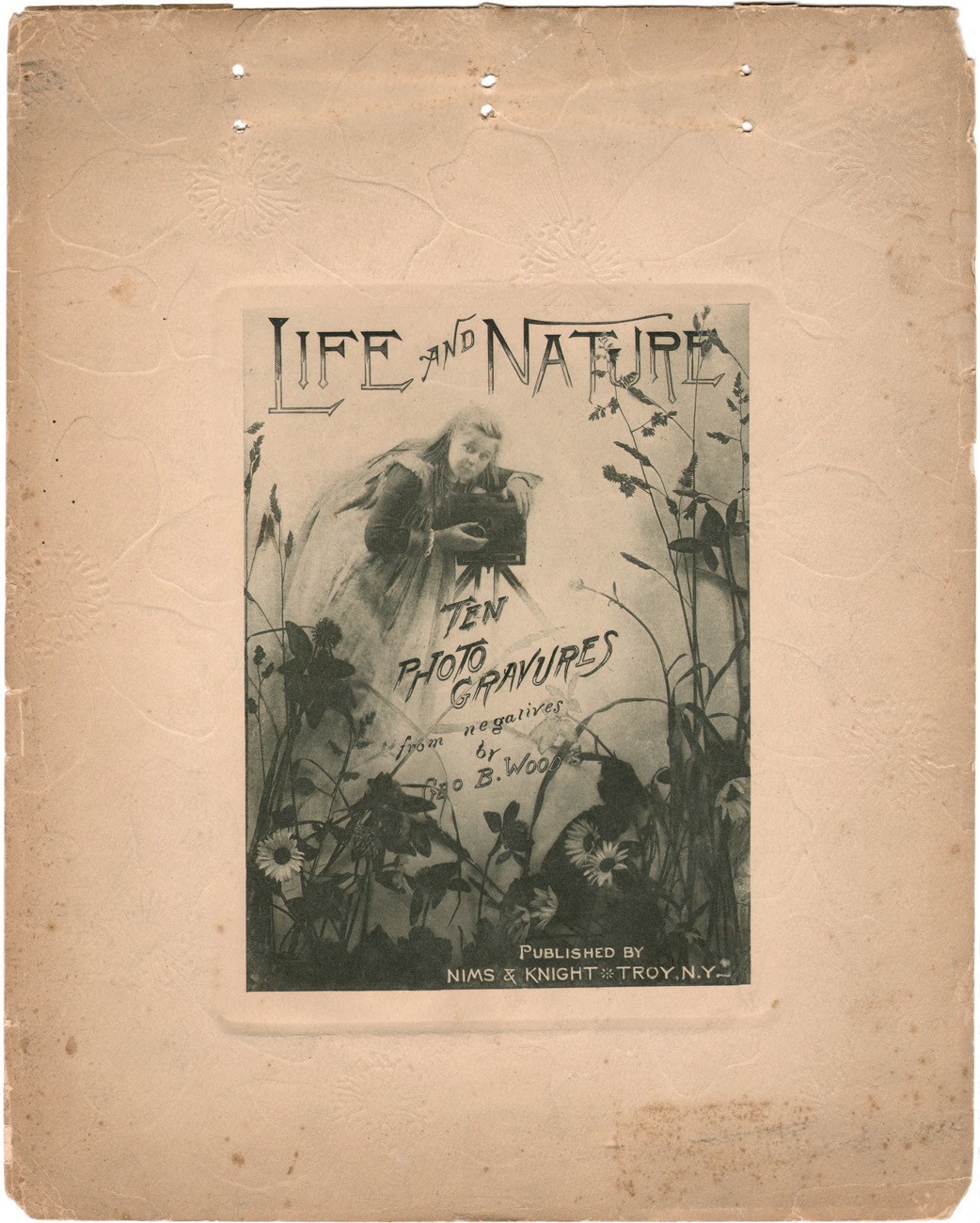

Life and Nature

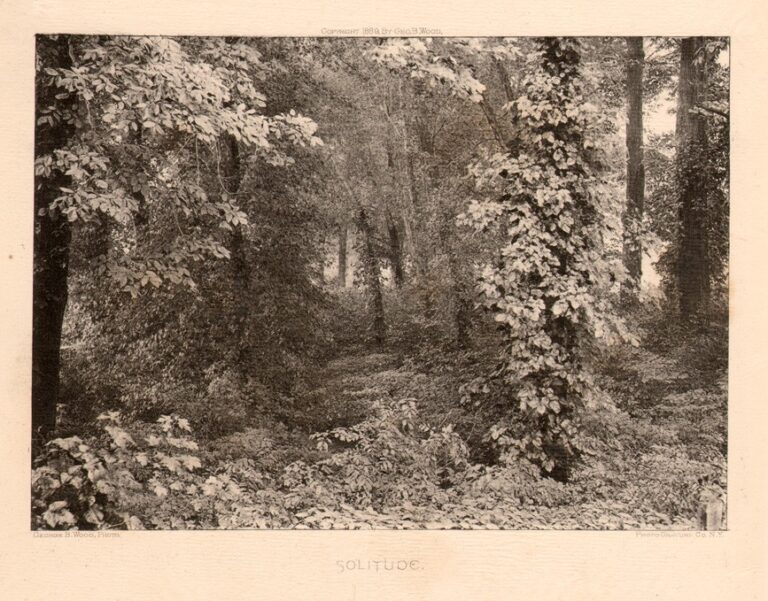

Due to the nature of the translucency of these tissue gravures and the mild reality of slight age-toning to the plate leaves, we have endeavored to be as accurate as possible in their presentation with an emphasis on color accuracy. Plate pagination for this volume, as well as all material (grouped as volumes, portfolios, journals, etc.) found on PhotoSeed, follows in the original order in which it is collated specific to the individual work.

Volume Particulars

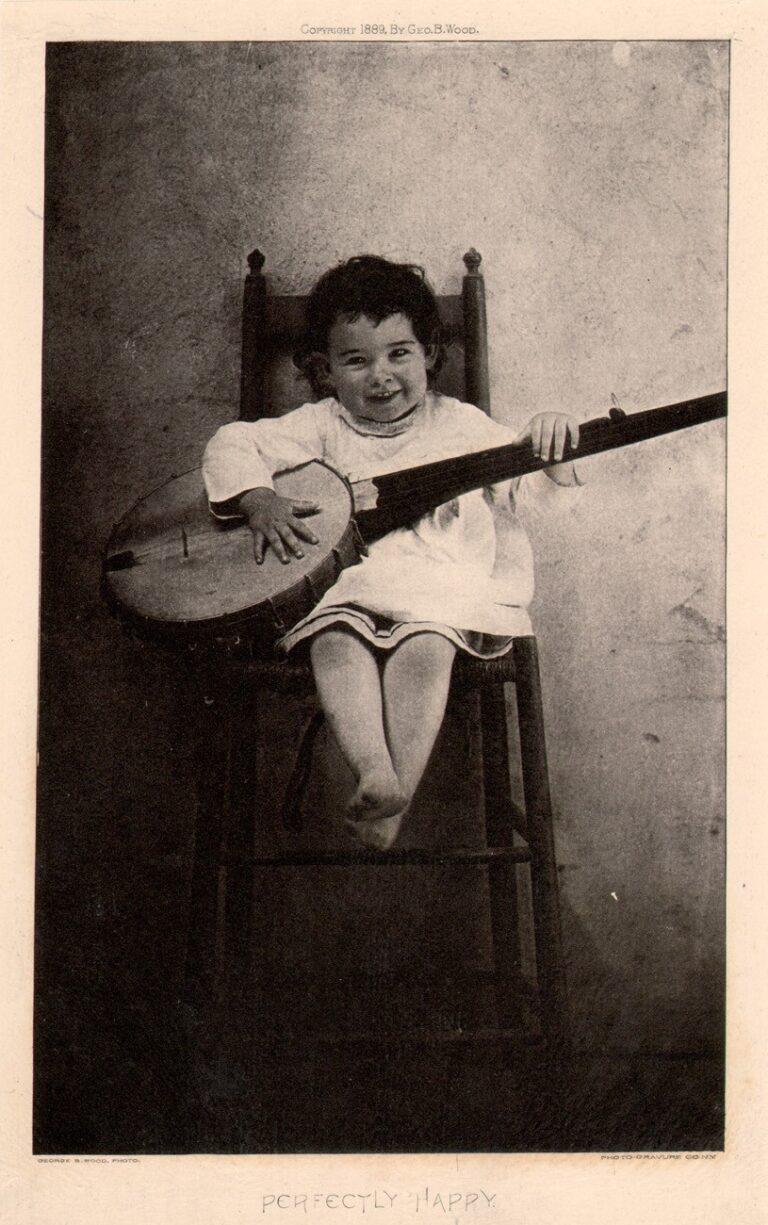

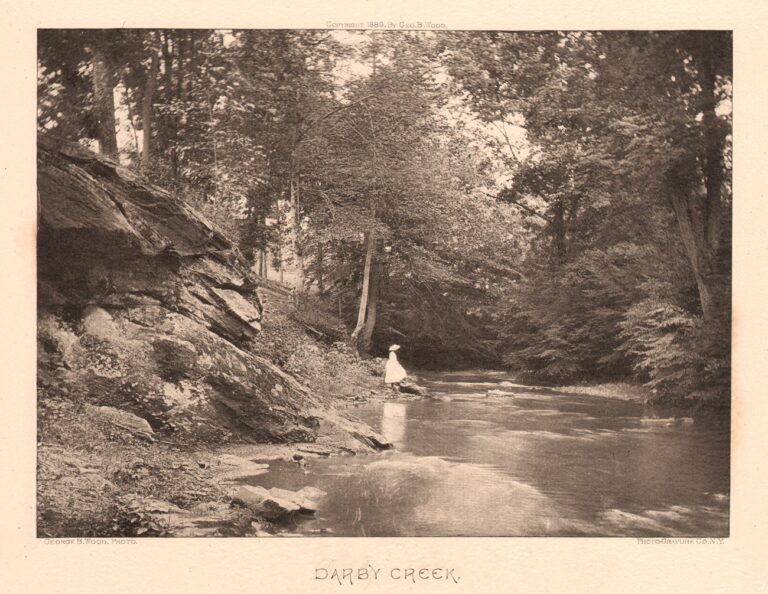

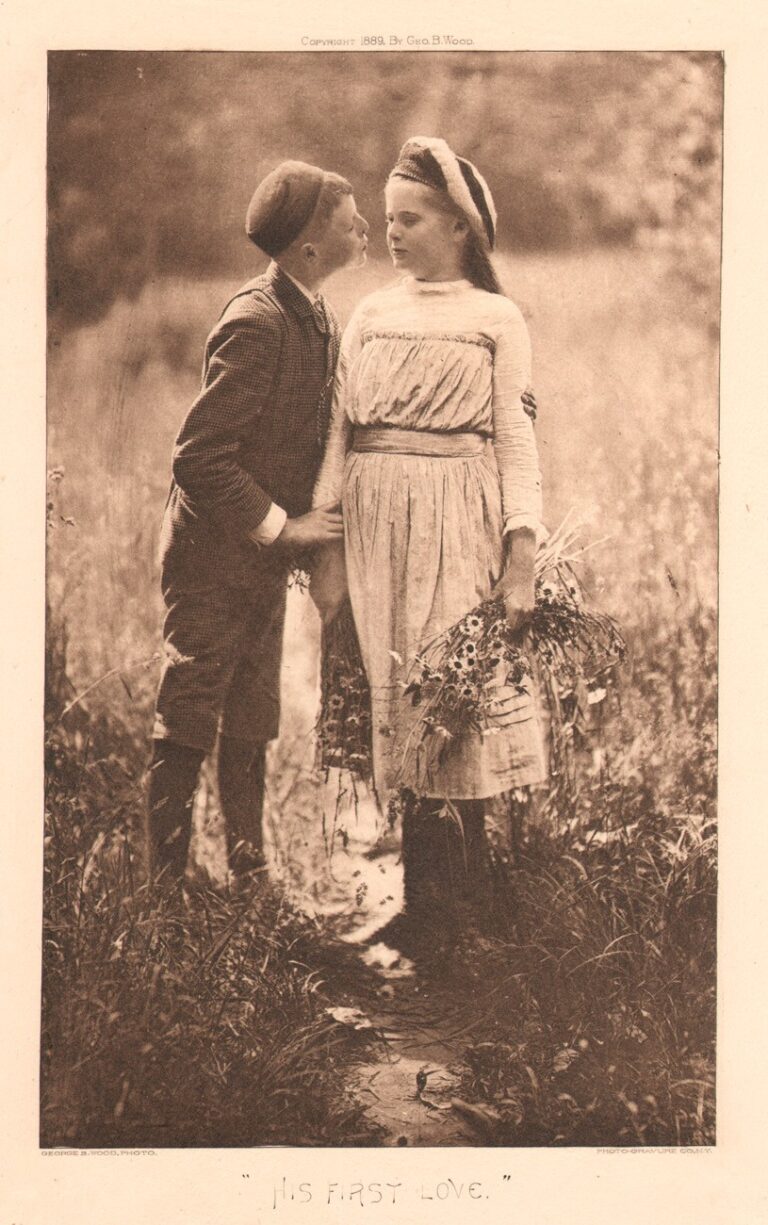

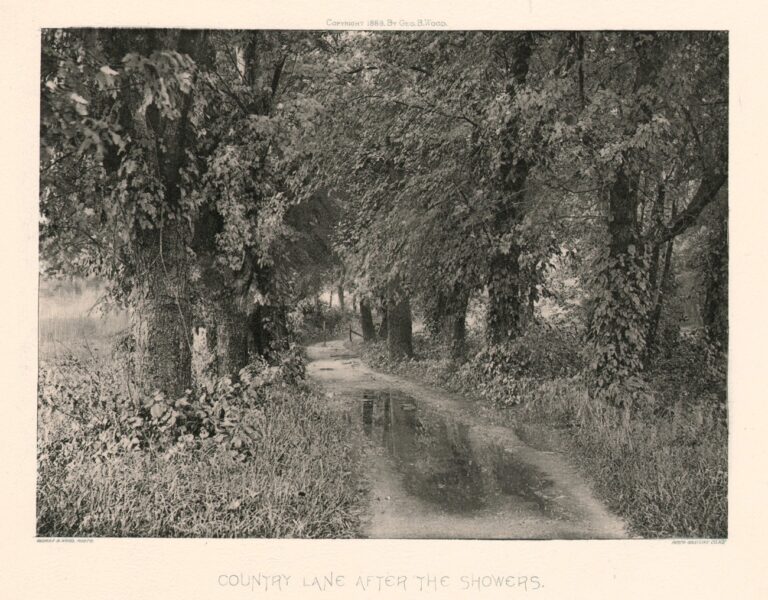

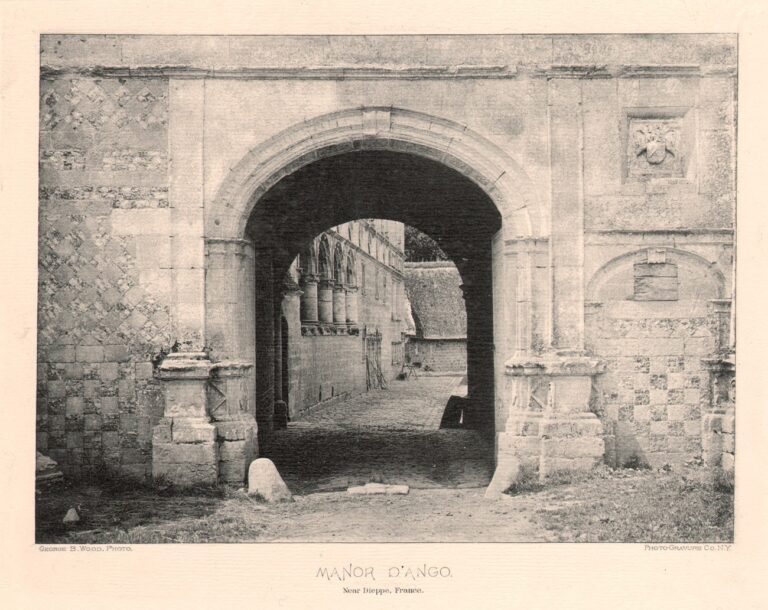

Photographic images contained in the view album Life and Nature, featuring “Ten Photo Gravures from negatives by Geo B. Wood”, were individually copyrighted in 1889. The work was issued by Ernest Edwards’ New York Photogravure Company and published in the Fall of that year as Japanese tissue gravures by Nims & Knight of Troy, New York. The photographs, showing landscapes and genre work featuring his children around his Philadelphia home as well as an architectural view taken near Dieppe, France, were taken by George Bacon Wood Jr., (1832-1909) a Philadelphia artist who came to embrace amateur photography in a big way beginning in 1882.

Introduction

In the defunct magazine American Art & Antiques, the important American art historian and curator Donelson F. Hoopes, (1932-2006) wrote an insightful article in 1979 on the American painter and amateur photographer George Bacon Wood Jr., (1832-1909) believed to be the first lengthy account done on him since Wood’s oldest daughter Elizabeth had penned a 1916 posthumous volume of her childhood growing up in the Germantown neighborhood of Philadelphia between the American Civil War and 1900. Titled George B. Wood, Jr. : A Student of Nature, Hoopes article concentrated on Wood’s career as an artist, briefly touching on his “emerging interest in photography” :

“The transition from painting to photography was an easy adjustment for Wood; his oils and watercolors usually had been diminutive works with strong emphasis upon exact description.” (1.)

Unbeknownst to his readers, Hoopes was approaching his subject matter in a most personal way, as the artist’s great-great-grandson. (2.) Indeed, this would seem consistent with Wood being “indifferent to fame” and as a “quite unassuming Quaker.” (3.)

Brief Biography: George Bacon Wood Jr.

George Bacon Wood Jr. was born on January 6, 1832 in Pennsylvania (4.) and died at 77 years of age on June 17, 1909. (5.) His father, Dr. George Bacon Wood, (1797-1879) was a founder of the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy and later professor of the Theory and Practice of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. (6.) As stated earlier, he came from a Quaker family:

“Wood was an unassuming man, as befitted his Quaker background, and was not inclined to seek fame or fortune.” (7.)

As an artist, Wood “studied from Nature” and at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, in addition to taking “the advice of artist friends.” (8.) After his death, his daughter Elizabeth would write:

“My parents were of Quaker origin, my father following this religion to the end of his life. His mother and father were very strict in their beliefs and this made the study of art a difficult one for him, for an artist in those days was looked upon by Quakers as almost predestined to the loss of his soul. My father’s aspirations doubtless caused much unhappiness to his parents, and his study of art under this disapproval was erratic and pursued almost entirely alone. Persistence, however, carried him to success.” (9.)

He married Julia R. Wood (1834-1887), and had seven children by her. (10.) Unfortunately, Julia died young, after suffering a spinal injury after being thrown from an open stage while in the Adirondack Mountains in New York state. Her daughter recounts her strong faith towards the end of her life:

“My thoughts often rush back to my mother’s dear sick room in our Germantown home, where in her wheel chair she sat so patiently, filling the air with the glory of her goodness, and giving out to others cheerfully strong hope for the wondrous life to come, and help for the troubled life on earth.” (11.)

Hoopes wrote concerning one of Wood’s earlier artistic efforts, at the age of 26, describing a watercolor study of Niagara Falls he did titled Niagara from Table Rock, which he entered in the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts annual exhibition in 1858. We further learn Wood had done the piece without any evidence he had ever actually visited the Falls, but as an affirmation that landscape painting was of supreme importance to him, having surely been influenced by seeing painter Frederic Edwin Church’s Niagara done in 1857. (12.) Because of his Quaker faith, Wood the artist “tended to eschew the study of the human figure, a deficiency which is sometimes revealed in his awkward handling of this element in his genre paintings.” (13.) Later, Hoopes recounts this faith “precluded him from participating” in the American Civil War. (1861-1865) Wood continued to paint, and two years after the war’s conclusion in 1867, he began making annual summer trips to Elizabethtown, on the Bouquet River in New York state’s Adirondack Mountains, where he painted while maintaining a studio. (14.)

In 1882, Wood took up Photography, which we will explore in the following chapters. The next year, 1883, he visited Europe for the first time-combining both disciplines of lens and watercolor brush. Some of the places he visited included France, Germany, Italy, and Switzerland. Later, according to Boston’s Childs Gallery, Wood returned, visiting Switzerland in 1898 and 1899, where he executed a series of watercolor drawings, “believed to be his final works.” (15.)

Wood was a member of the Philadelphia Sketch Club in the 1870’s and later in life, a member of the Salmagundi Art Club in New York City after he had moved there from Philadelphia around the turn of the century to live on Staten Island with his eldest daughter Mary. As a member of the Salmagundi Club, it is not known if he was still actively painting at the time he delivered a lecture to members of The New York Camera Club on May 10, 1900 titled: “The Camera in the Hands of an Artist”. (16.)

Around this time towards the last decade of his life, Wood spent winters in West Palm Beach, Florida and continued his artistic pursuits by photographing and drawing various marine specimens he encountered in the state through the winter of 1907. These were sent by him for additional study to the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia:

“The most important collections from this State were made during several winters, in 1904-5, 1906, and 1907, by the late George Bacon Wood, while at West Palm Beach. The marine species were all collected on the ocean front at Palm Beach. Mr. Wood sent photographs or drawings of many of the larger and more abundant and he also ascertained the vernacular names when possible…” (17.)

The Artist becomes a Photographer

Ten years after he became an amateur photographer, his fellow Photographic Society of Philadelphia colleague Clarence B. Moore wrote of Wood:

“George B. Wood of Philadelphia (Photographic society of Philadelphia) took up photography in 1882 and made a name for himself from the very start, for while so many other amateurs at that time contented themselves with the simpler branches of photography, Mr. Wood at once started upon genre work, for which his training as an artist so peculiarly fitted him. The remarkable grace and beauty of his poses gained not alone the admiration of the visitors, but the recognition of the judges at exhibitions where he saw fit to compete.

As to his specialty, Mr. Wood writes: “In regard to artistic photography I think it a thing that must come naturally to one. Have something to say ; put business into your pictures, i. e., make something going on and being done as people would naturally do it, and secure good effects of light, and black and white.

I hardly think it can be done by any rule or set of rules.” (18.)

It was in the Spring of 1882 that Wood decided to become a photographer. As recounted in her 1916 volume “A Girl’s Life In Germantown”, written by his youngest daughter Elizabeth W. Coffin:

“Above the woodshed, which was attached to the barn, my father had a studio built, with a north window, skylights, and an outside stairway. He had seen the announcement in a newspaper that the dry plate had been invented, and he immediately became interested in photography, since the dry plate made the process easier and more reliable. This outside studio he used chiefly to work with his camera, and my brother Whitney and I were continually made to pose as models. At one time we became deeply interested in a competition for a prize offered for the best amateur photographs illustrating Hiawatha, but for the photographs we got only honorable mention.

My father received many prizes for the photographs in which we children posed, and for others in which we did not appear. A little head of me took the gold medal at a Paris Exposition. Once Queen Victoria, having seen some of my father’s photographs at an exhibition abroad, requested copies of them, and my father had a book made up for her and sent her.” (19.)

Uncooperative Bovine is his First Instructor

Perhaps the best known account of Wood’s immersion with the practical and technical hurdles he had to overcome in becoming an amateur photographer can be found in the December, 1882 issue of The Photographic Times and American Photographer. Printed here in total, Wood’s adventure in Photography begins with an amusing story of his tenacious pursuit of one very uncooperative cow:

“The recent discoveries in photography in the bromo-gelatine dry plate process, rendering the use of the camera accessible to every one that has the time to devote to it, persuaded me, after long and patient deliberation, to become the possessor of a camera, and upon consulting the knowing ones a lens was purchased; then the plates were procured, and a bath room was converted into a dark closet.

The requisite arrangements being completed, the amateur performance commenced in the opening in this closet, heated beyond endurance by the circulating boiler and no ventilation, of a package of bromo-gelatine plates, so mysteriously done up in total darkness.

No man ever attacked the wild beast in his lair with more awe than I did these same plates. However, the feat was accomplished, and I emerged a reeking mass, with the restless demons inclosed in three double backs, and out we started— the demons and I—to drag into our net anything we might see fit.

The focusing business was gone through with, the slide withdrawn, when the cow, that was the object to be obtained, moved off. A fresh aim was taken, but the focus must be out, so off comes the back. There! the demon’s gone. I forgot that slide.

Well, try again. So fixed the focus, reversed the back and withdrew the slide, when, the cow getting into a very ungainly position, I attempted to get a little grace into her. In glancing at the camera, however, I saw, to my horror, that the cap was off, and that all our movements were being recorded in a most criss-cross and varied style, beyond all recognition. So there goes demon No. 2.

Guess cows are a hard thing to go for anyhow, so we will hold them in reserve for future efforts and saunter along—the remaining demons and I—when we come to a beautiful nook with running water, all glistening in the sun. We undo our traps again, and set up afresh. On looking into the camera, see a great white place—that won’t do! Can’t focus it out, so retire in disgust from the beautiful nook, forsake the high flights of Nature, try to take a tree on the lit up side, and, getting everything correct this time, open fire. The exposure—what ought it to be? Having got in the big stop, we will give fifteen seconds, and rejoice in the anticipation of seeing that tree just as I saw it in Nature, after the plate is developed. Poor deluded mortal!

We tug our way onward, the weather not very conducive to exertion, to make other efforts.

This time a picturesque old barn, among pollards, etc. We focus on it, put on the double back, withdraw slide, and doff the cap. The stop being the same, we give the subject ten seconds, being of lighter local color with more illumination than the tree. Put in the slide—pshaw! then the cap—wonder what that will do, will it fog the plate? Pack up and start for fresh laurels, which can always be found on our Wissahickon, and select a dense place, which we desire, so open up. To get detail, we put in smallest stop and give two minutes’ exposure. This time everything seemed to run smoothly, and, pointing for home, wondered how soon our experienced friend could develop the plates. Take the first train for the city, and he says “may possibly do them in course of next week.” Well, that’s a long wait under the circumstances, but the time finally comes round, and we resort to our friend, who says:

“Over-exposed! could hardly get any image of the tree. The barn is a little better, but you did not level the camera— it’s all distorted. One plate I couldn’t for the life of me get anything on—you must , have forgotten to withdraw the slide—and the other is badly fogged from some cause or another, I don’t know what.”

Disappointment sat heavily upon my brow, but I got some more plates to try it all over again, only more so.

Then my friend said I ought to develop the plates myself, as, knowing the light and subject and exposure, I was the only one who could properly do it. This was all very nice, but I hadn’t the faintest idea of how a plate ought to look when developed; besides, I seemed to have my hands full in focusing and exposing. So I concluded he would have to do the developing till I got better up in what I had already undertaken.

If any one has made any error of action that I have not, I should greatly like to know what it can possibly be, for I have removed the back without inverting the slide; failed to have the cap on when needed; neglected to withdraw the slide; not leveled the apparatus; totally ignored the swing-back; focused badly; moved the camera so as to miss much of the subject; have had to return home for part of the equipment; forgotten to tie up package of plates; inserted film side of plate next to partition; also neglected to insert partition in the double back after removing an exposed plate before opening closet door; have dipped exposed plate in hypo, first, and doubtless other faults I do not recall.

It is now some eight months since I began this experience, and even to this day I commit innumerable errors, although I begin to do things intuitively, seldom failing to withdraw the slide, and generally having something on my plate when I develop it. Still, if it is at all slow in coming up, I greatly fear some important part of the operation has been omitted.

Yet, notwithstanding all this aggravation, success has perched on my camera at times to the most charming extent, and I am as infatuated, and following the phantom as eagerly, as any ill-fated boy after the “Will-o’-the-Wisp.” (20.)

Photographic Timeline: 1882-1893

The period of serious photographic pursuit for Wood lasted approximately a decade, from 1882 to his official resignation from The Photographic Society of Philadelphia in 1893. The following chronological articles mentioning Wood in relation to amateur photography were taken from source material from this period.

1883

Speaking about the Photographic Society of Philadelphia, a “special correspondent” for The Photographic Times and American Photographer in 1883 remarked in its’ pages:

“It is real gratifying to see how many artists (painters, etchers, and engravers) are members of this live Society. John Sartain and Samuel Sartain, his son, are among the eminent and older members. John Moran is also an old member, and I think his brother-in-law, Ferris, also belongs to the ranks. George Wood, the well known painter and artist on wood, also finds much to help him here. He has just a week or two ago returned from Europe with some fine emulsion exposures, which he will probably make available for Harpers Monthly and the Century Magazine.

Mr. Wood related some of his experiences, and said that when he came into port he “declared” his lenses, plates, etc., to be a part of his “working tools,” and therefore had no trouble with the Customs officials. Lucky Mr. Wood!

Among his fellow passengers was Mr. George Hanmer Croughton and family. Mr. Croughton is one of the best crayon and color artists England ever gave to the world, and has come to America to live and work, and intends settling in Philadelphia.” (21.)

1884

This same “special correspondent” for the journal in 1884 remarked:

“The meeting adjourned at 10 p.m. to enjoy an exhibition, by Mr. William H. Rau, of lantern slides, made from negatives of Mr. George Wood. The subjects were artistic, and the quality of the slides highly spoken of for their brilliancy, clearness, and softness of tone. They were upon collodion plates and toned with sulphide of potassium.”(22.)

1888

A press notice of Wood’s work from the annual exhibit of The Photographic Society of Philadelphia appeared:

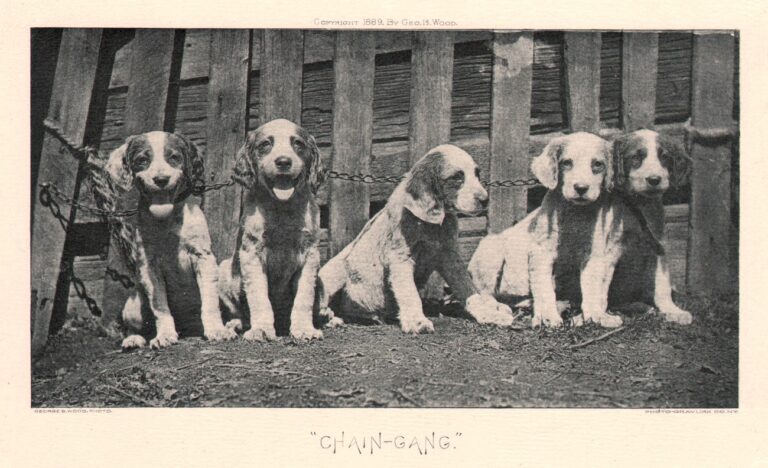

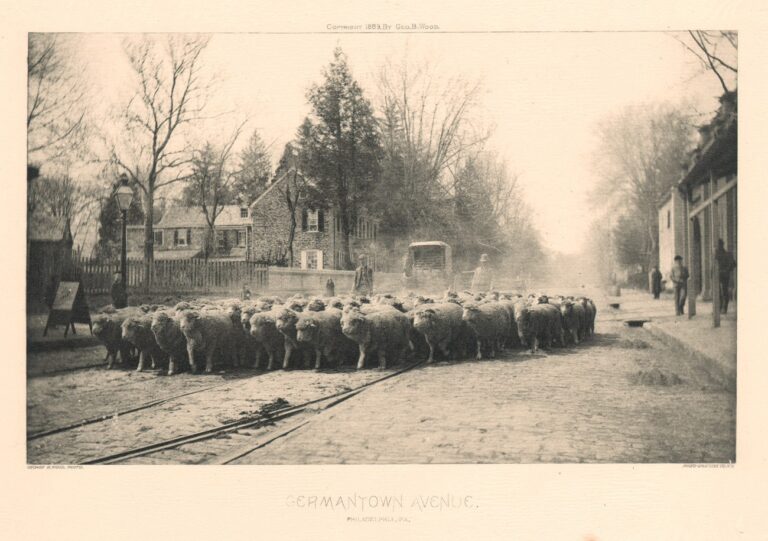

“As usual, George B. Wood displayed a large variety and number of 6½ by 8½ photographs, and carried off two diplomas. Five of his frames were on the floor. 39, entitled ” The Dog Show,” showing four pretty little girls queerly dressed, standing in a row, each holding a puppy, was capitally done and very clear. 41, called “Driving Sheep, was a very pretty study of animals.

Another interesting study, entitled ” Day before Christmas,” in 49, showing a boy walking off with a turkey and a girl looking on with her pet dog near by, was particularly good. A very natural picture in 53 was called “Leetle hard of hearing,” illustrating a boy trying to talk to a dear old man. Most of Mr. Wood’s pictures were made instantaneously, and were good, technically speaking.” (23.)

Commentary for the seventh photograph presented with the pagination for Life and Nature- Watering His Horse– similarly reproduced as the frontis plate photogravure for the 1889 volume of The American Annual of Photography and Photographic Times Almanac follows:

“Watering His Horse,” the charming child study from Mr. Geo. B. Wood’s negative, speaks for itself. Mr. Wood showed his artistic qualities by the arrangement and grouping of the children and their playthings, the old well-curb and its bucket. Not the least charm, to many eyes, is the vague yet effective background. Indeed, this picture might appropriately be offered as an illustration of Mr. Champney’s paper, “Out of Focus,” so well does the latter apply. To say that the plate itself is the work of the Photogravure Co., of New York, is enough praise, and is equivalent to saying that it is done in the very best possible style of the art.” (24.)

And the following report by The Photographic Society of Philadelphia:

“In pursuance of the resolution passed at the last meeting, the chair appointed Messrs. Geo. B. Wood, John Carbutt, Sr., and David J. Hoopes, a committee to collect portraits and autographs of members of the society, to be preserved in an album provided for the purpose.” (25.)

Commentary for a variant to the sixth photograph presented in the pagination for Life and Nature- Chain-Gang-showing a litter of puppies, as well as the eighth plate: Germantown Avenue, showing sheep being driven down the road with Wood’s stone home in the background, appeared in the periodical The American late in the year:

“Mr. George B. Wood has on exhibition in a Chestnut st. window, a recent production entitled “He’s a Lucky Dog.” It represents a litter of fox-hound pups waiting for their breakfast. One of them has succeeded in working his way out between the bars of the kennel, and is plunging head and forepaws into the dish of milk which stands in the foreground just beyond the noses of the pack. The little yelpers are all straining and scrambling to get out and join their fortunate companion. The varied expressions of their canine countenances are immensely entertaining, showing eager resolution, disappointment, envy, impatience, and hungry greed with comical significance, and yet without overstepping the modesty of nature. Mr. Wood has opened a studio on the top floor of the Drexel Building, where he is very pleasantly fixed, with good light, above the reach of smoke and dust, quiet, secluded, and yet conveniently accessible. He has several noticeably attractive pictures recently finished or well under way, one of the most important being a road scene in the Germantown region, with a flock of sheep in the foreground.” (26.)

1891

At Vienna’s ground-breaking 1891 International Exhibition of Art Photographers, (Internationale Ausstellung Künstlerischer Photographien in Wien) in which the photographs making up the entire exhibit were judged collectively on artistic merits, only 25 photographs from 4000 submitted world-wide were accepted for exhibit by ten American photographers. After Rochester’s John E. Dumont’s six accepted entries, George B. Wood had the honor of five being accepted-tying him with Alfred Stieglitz, the future founder of America’s Photo-Secession:

“The report comes that out of 40 American exhibitors contributing 350 photographs, 30 were thrown out with their work, and but 25 photographs of the 10 accepted, were hung, as follows: Exhibitors from New York: James L. Breese, 2; Alfred Stieglitz, 5; Miss Mary Martin, 1; Harry Reid, 1. From Rochester, N. Y.: John E. Dumont, 6. From Philadelphia, Pa. : John G. Bullock, 2; George B. Wood, 5. From Chicago: Mrs. N. Gray Bartlett, 1. From Buffalo, N. Y.: H. McMichael, 1. From Lowell, Mass.: George A. Nelson, 1.” (27.) A discrepancy exists however as a periodical account published in 1892 stated that six of Wood’s photographs were hung. (see following chapter: Awards)

1893

Sometime in late 1892 or very early in 1893, Wood tendered his resignation from the Photographic Society of Philadelphia:

“Resigned.—We regret to announce that Mr. George Wood, the well-known artist and photographer, has severed his connection with the Photographic Society of Philadelphia. Mr. Wood was a useful, conscientious worker, and his loss will be felt by the Society at large. Resignations from the Society have been entirely too frequent of late.” (28.)

Awards

From an earlier article referenced here and written by fellow Photographic Society of Philadelphia colleague Clarence B. Moore shortly before Wood’s resignation from this organization, a lengthy list of awards bestowed on Wood were listed:

“In prize winning Mr. Wood can hold his own with the most successful, as the subjoined list will show:

Boston Society of Amateur Photographers, 1884— Four prizes. Subjects given to be illustrated: Happiness. Flowers. Indecision, Haymaking.

Same society. 1885—Three prizes. Copies of Paintings; Grand Prize for Best Entire Exhibit; Highest Excellence in Composition.

Joint Exhibition. Philadelphia, 1886–Three prizes.

Photographers’ Association of America (professional), St. Louis, 1886—Silver medal; Chicago, 1887—Gold medal.

Photographic Society of Great Britain. London, 1886 —Bronze medal.

Joint Exhibition. New York, 1887—Diploma.

Joint Exhibition. Boston, 1888. Three prizes, for Superior Animal Composition ; Excellence in Figure Composition ; Entire Exhibit.

Joint Exhibition. Philadelphia, 1889—Diploma for entire exhibit.

Paris Exposition. 1889—Bronze medal.

Camera club, Chicago, 1889—Three Bronze medals.

Vienna. 1890—Silver medal.

Vienna Salon, six pictures hung, 1891 Grand diploma.

Mr. Wood uses three Dallmeyer and two Ross lenses.” (29.)

Photographic Epilogue

Wood continued to take pictures as late as 1907, while wintering in Florida and documenting marine specimens he photographed and sent to the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia for further study. In researching Wood’s career as a photographer and painter for this website, the following wry observation by Alfred Stieglitz appeared after Wood had delivered a lecture on May 10, 1900 to members of The New York Camera Club. With pun unintended in respect to this talk, it seems unfair to paint Wood’s photographic work with too broad a brush, given his many obvious talents outlined here in both disciplines of painting and photography, but instructive nonetheless for the weight Stieglitz’s opinion held:

“On May 10, Mr. George B. Wood, of the Salamagundi Club, (sic) a painter by profession, and an amateur photographer of quite some repute twenty years ago, delivered a lecture, “The Camera in the Hands of an Artist,” illustrated with slides. Truly, the title of the lecture was promising enough to pack the hall with an expectant audience, who had come to listen and to learn. Unfortunately the title had been misinterpreted by the majority who had come to learn; a serious lecture had been expected, while Mr. Wood treated the subject from an entirely different point of view.

“One of the Mouths of the Mississippi,” a young negro boy biting into a watermelon, will illustrate the general tone of the lecture.” A.S. (30.)

Notes

1. Donelson F. Hoopes: George B. Wood, Jr. : A Student of Nature: in: American Art & Antiques: Billboard Publications Inc.: New York: Vol. 2: issue 5: September/October 1979: p. 125

2. Provenance tree: Christie’s Auction House: New York City: sale of painting The Fifteenth Amendment (Civil Rights) by George Bacon Wood : Sale 9866/Lot #95: November 29, 2001

3. Hoopes: p. 119

4. United States Census: 1880: George B. Wood

5. obituary notice: The New York Times: June 19, 1909. Wood is buried at West Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia.

6. Wood biography: The College of Physicians of Philadelphia (Historical Library and Wood Institute): site accessed: 2012

7. Hoopes: p. 118

8. Ibid

9. Our Quaker Faith: by: Elizabeth W. Coffin: in: A Girl’s Life in Germantown: Boston: Sherman, French & Company: 1916: p. 14

10. siblings: oldest to youngest: 1880 U.S. Census: Mary M. Wood-born 1860; Anna C. Wood- born 1862; Lucy W. Wood (but possibly Lucia)-born 1864; Henry C. Wood-born 1865; Julia Deb. Wood-born 1870; George Whitney Wood-born 1872; Elizabeth H. Wood-born 1874.

11. My Mother: by: Elizabeth W. Coffin:in: A Girl’s Life in Germantown: Boston: Sherman, French & Company: 1916: pp. 11-12

12. Hoopes: pp. 120-121

13. Ibid: p. 120

14. Ibid: p. 122 (photographic archive of Wood’s work at the Library Company of Philadelphia indicates he spent time in Elizabethtown as late as 1886)

15. Wood, George B.: artist biography: Childs Gallery website: accessed: 2012.

16. Club Entertainments: in: Camera Notes: Published quarterly by The Camera Club:: New York: Vol. IV: October, 1900: No. 2: p. 121

17. Henry W. Fowler: Cold-Blooded Vertebrates from Florida, The West Indies, Costa Rica, and Eastern Brazil: in: Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia: Volume LXVII: (1915) : Philadelphia: The Academy of Natural Sciences: April, 1916: p. 244

18. Leading Amateurs in Photography: by Clarence B. Moore:in: The Cosmopolitan: Vol. XII: February, 1892: New York: The Cosmopolitan Publishing Company: p. 427

19. Elizabeth W. Coffin: A Girl’s Life in Germantown: Boston: Sherman, French & Company: 1916: pp. 7-8. The Wood residence referenced here, now demolished, stood at 6708 Germantown Ave. (formerly 5502 Germantown) located just north of Westview St. in the city of Philadelphia.

20. The Photographic Times and American Photographer: New York: Scovill Manufacturing Company, Publishers: Vol. XII: December, 1882: pp. 464-465

21. Photography in Philadelphia: in: The Photographic Times and American Photographer: published by Scovill Manufacturing Company: New York: October, 1883: Vol. XIII: p. 543

22. Photography in Philadelphia: in: The Photographic Times and American Photographer: published by Scovill Manufacturing Company: New York: October, 1884: Vol. XIV: p. 555

23. Notes from New York: Boston Exhibition-New York and Philadelphia Societies’ Exhibits-Miscellaneous Exhibits: in: The Photographic News: A Weekly Record of the Progress of Photography: London: printed and published by Piper and Carter: Vol. XXXII: July 6, 1888: p. 419

24. The American Annual of Photography and Photographic Times Almanac for 1889: Edited by C.W. Canfield: New York: Scovill Manufacturing Company: November 2, 1888: pp. 35-36

25. The Photographic Society of Philadelphia: in: Anthony’s Photographic Bulletin: E. & H. T. Anthony & Co. publishers: New York: November 24, 1888: p. 692

26. Art Notes: in: The American (Journal of Literature, Science, The Arts, And Public Affairs): Vol. XVII: December 22, 1888: p. 157

27. The American Amateur Photographer: Volume III: Boston: The American Photographic Publishing Company: New York, N.Y. : July, 1891: pp. 268-269

28. notice: The American Journal of Photography: Edited by Julius F. Sachse: Philadelphia: published by Thomas H. McCollin & Company: January, 1893: Vol. XIV: p. 41

29. Leading Amateurs in Photography: by Clarence B. Moore:in: The Cosmopolitan: Vol. XII: February, 1892: New York: The Cosmopolitan Publishing Company: p. 427

30. Club Entertainments: in: Camera Notes: Published quarterly by The Camera Club:: New York: Vol. IV: October, 1900: No. 2: p. 121