Nach der Natur | After Nature

This is a foundational portfolio of hand-pulled photogravure plates edited and published in early 1897 by Franz Goerke. Its historical importance for the perception and promotion of artistic photography in Germany as well as the greater international pictorial photography movement cannot be understated. Further, the superb quality of the gravure plates set a new standard for the medium, one Goerke himself would soon go on to emulate and refine for his journal Die Kunst in der Photographie. (The Art in Photography: 1897-1908) In addition to showcasing all plates from this folio, we present translations of Goerke’s Preface and the entirety of Richard Stettiner’s essay included with the letterpress. A contemporary review of the 1896 Berlin Exhibition follows, and concludes with 21st Century analysis of forces leading up to the exhibition by Art & Photographic Historian Christian Joschke.

✻ ✻ ✻ ✻ ✻

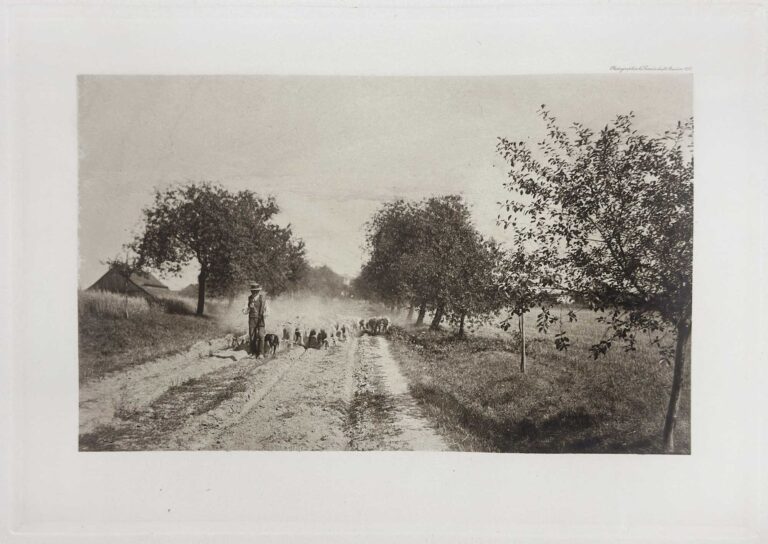

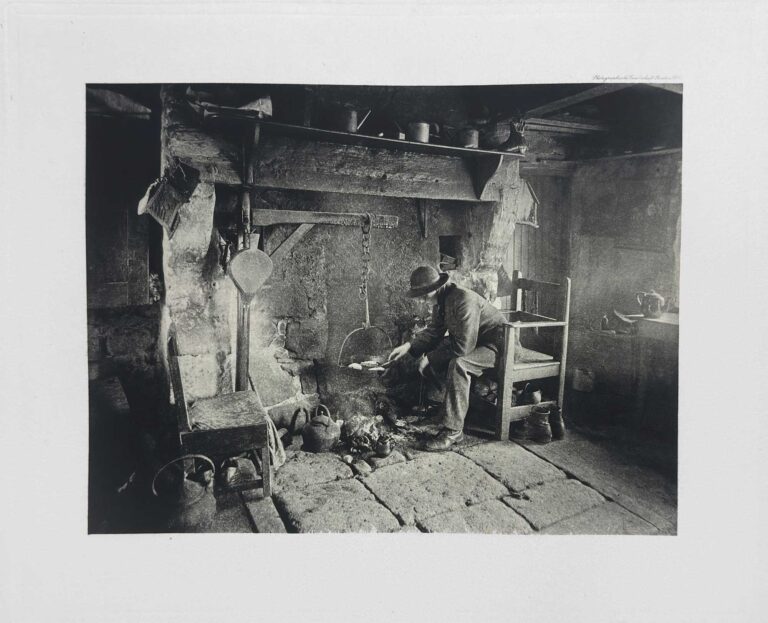

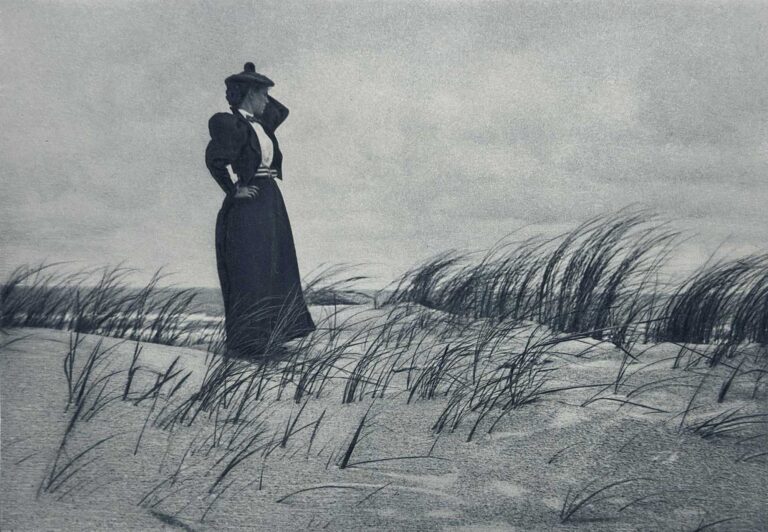

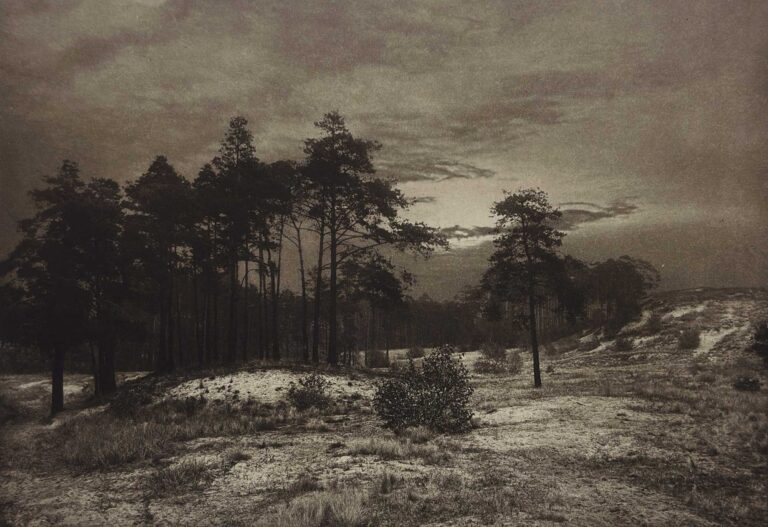

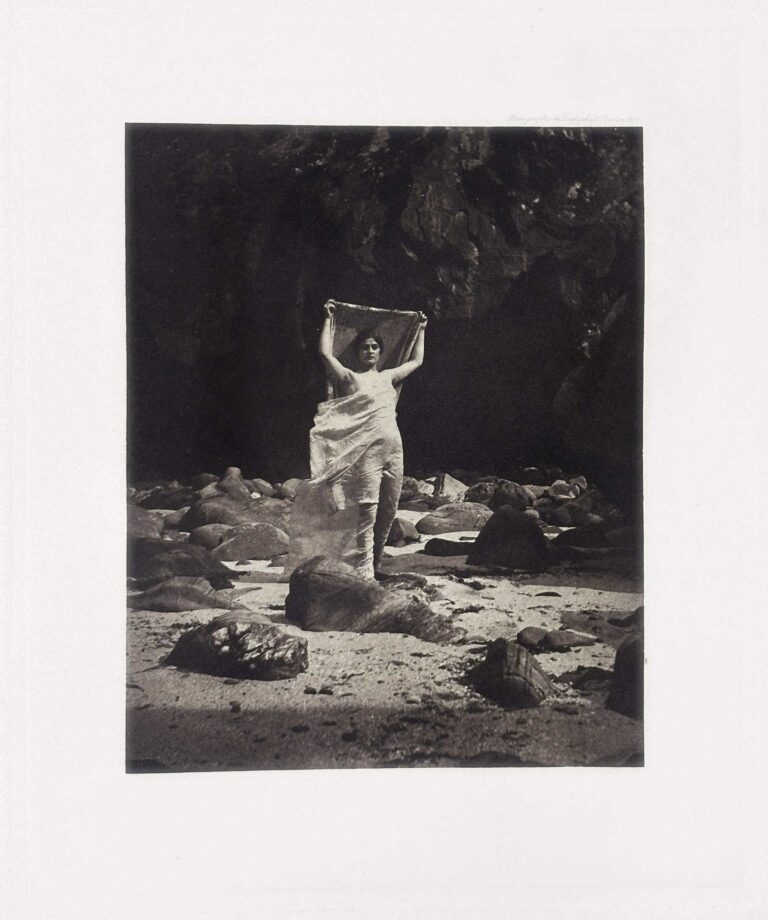

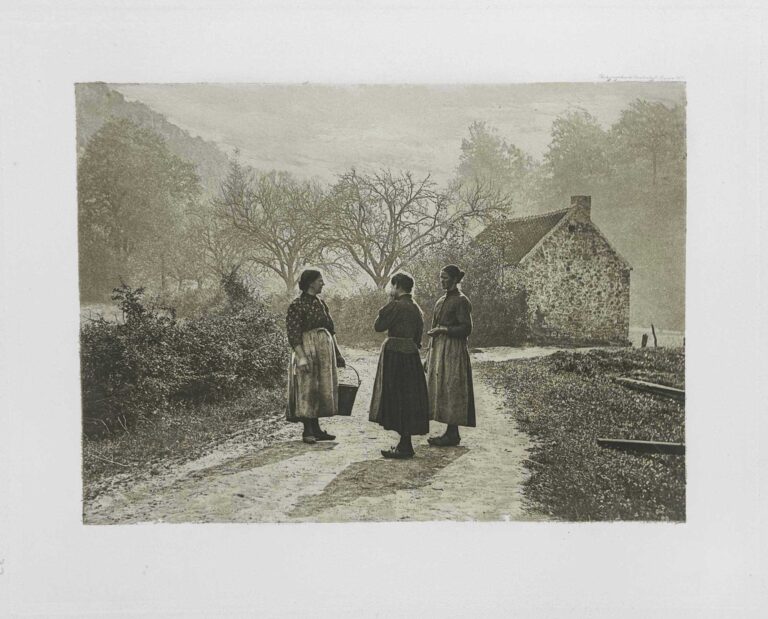

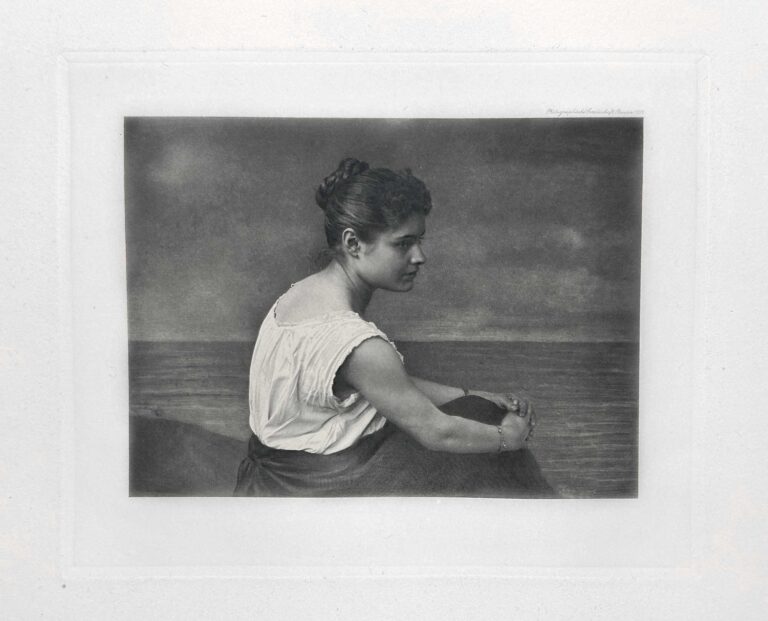

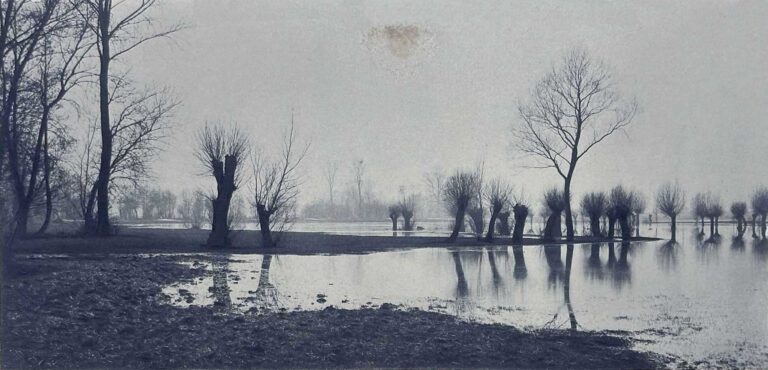

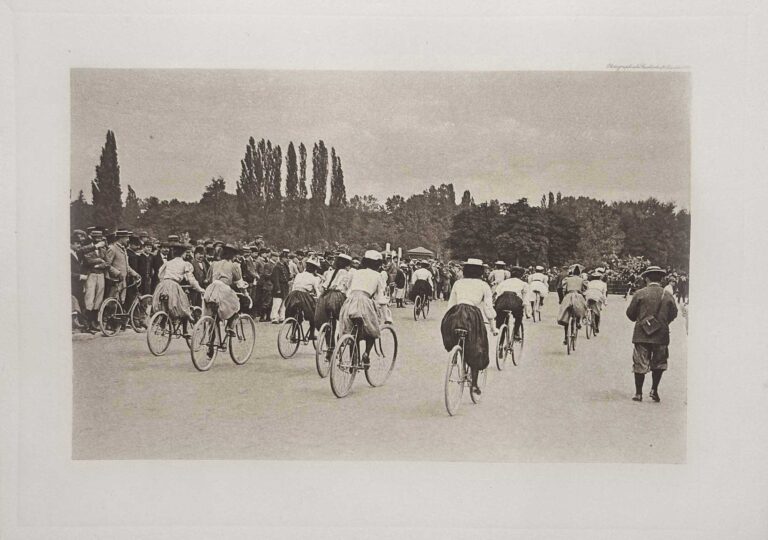

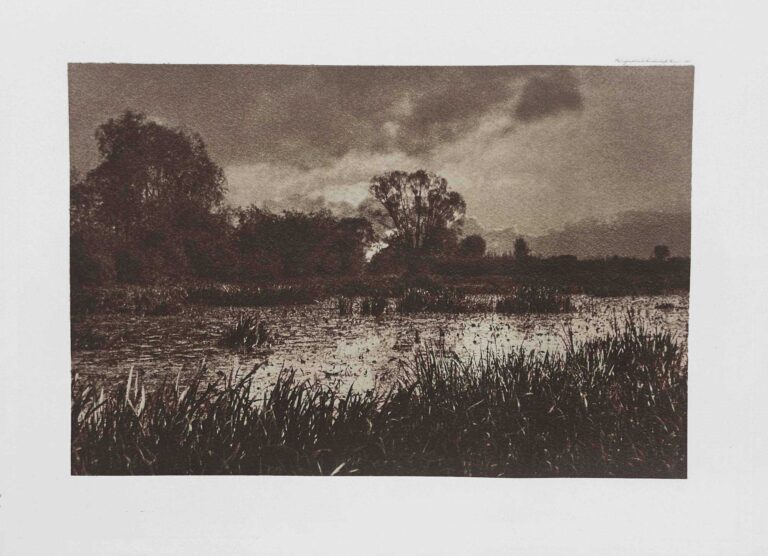

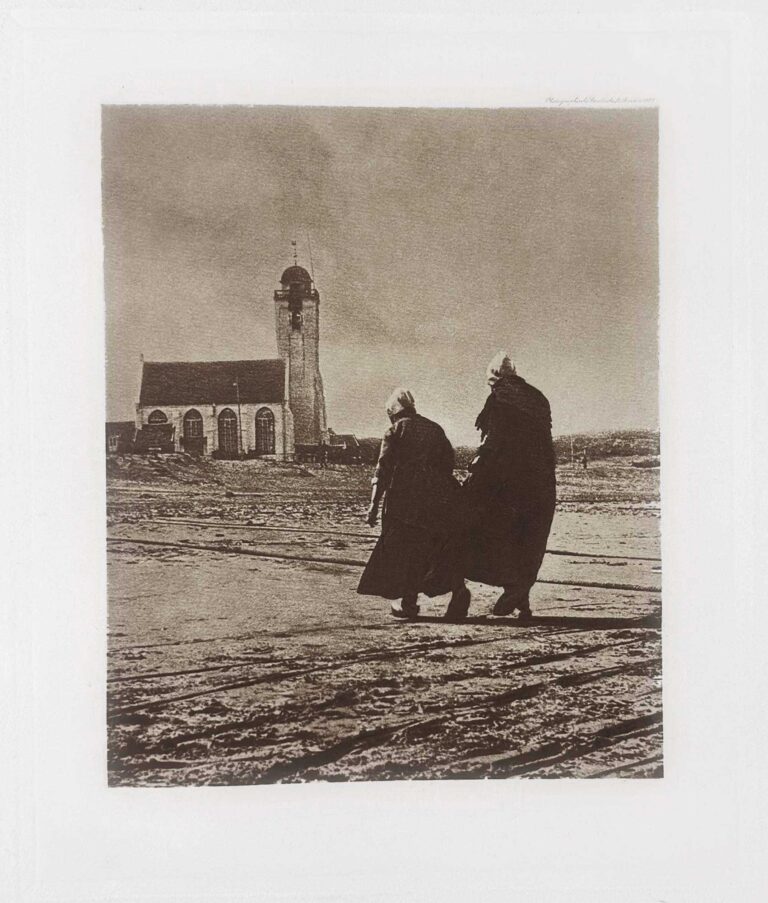

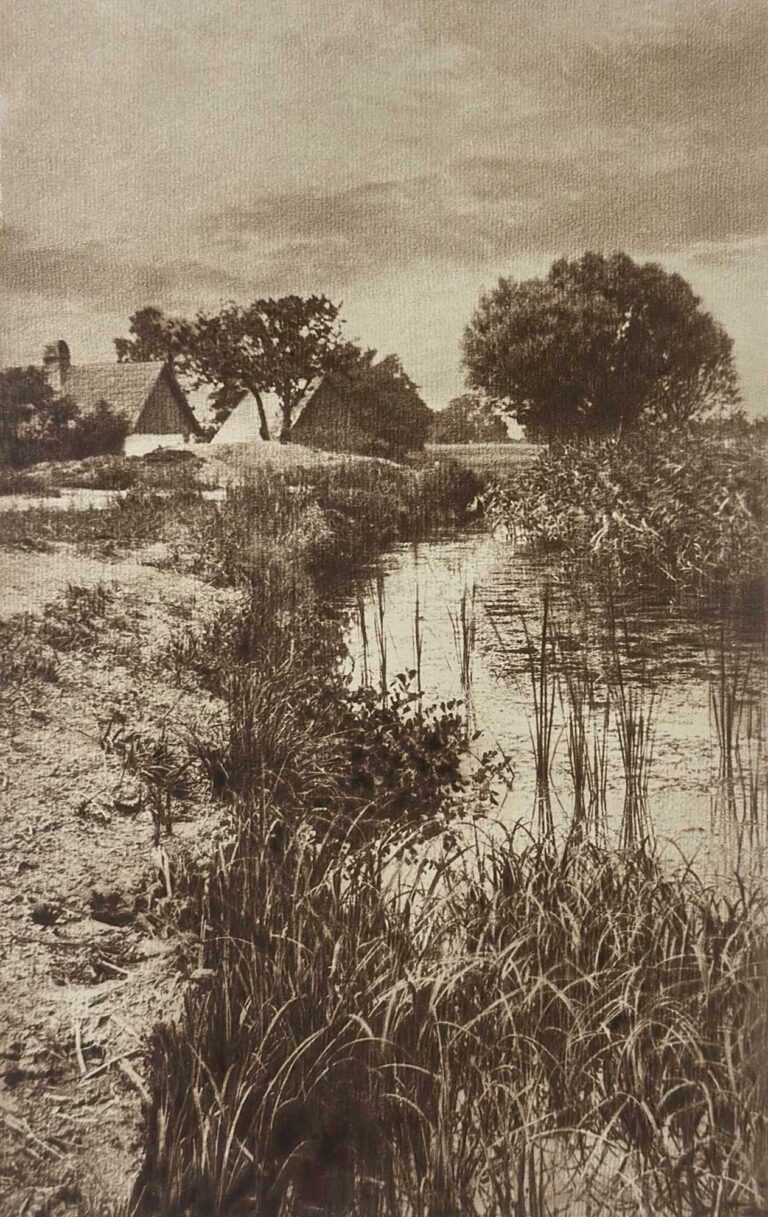

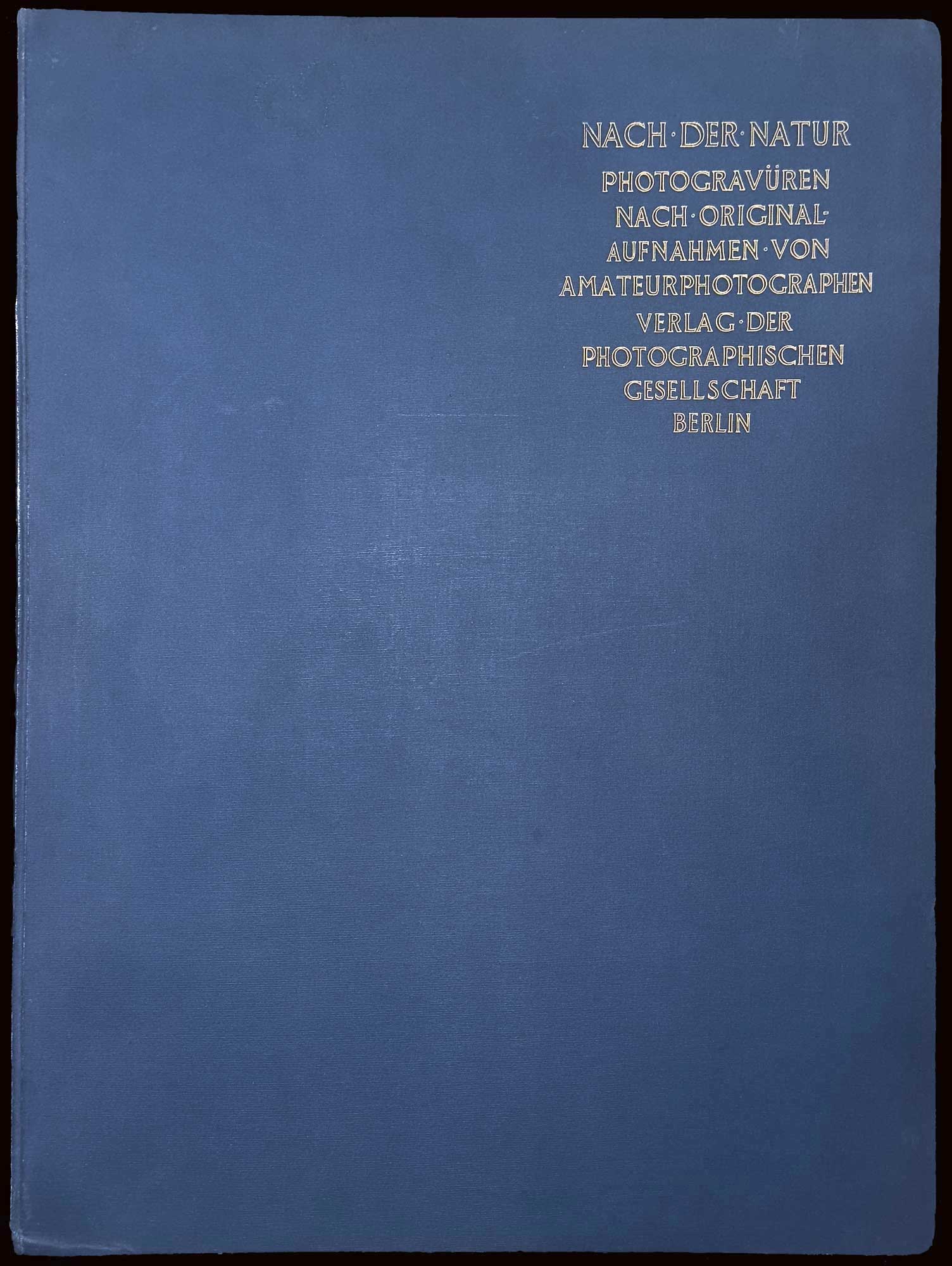

The elegant Nach der Natur (After Nature) was published at the request of the German and Silesian Society of the Friends of Photography by the Berlin Photographic Company to commemorate the 1896 “Internationalen Ausstellung für Amateur-Photographie” (International Exhibition of Amateur Photography) in Berlin. Nach der Natur contained thirty-two photogravures (including Stieglitz’s Scurrying Home), each so superb that Stieglitz was moved to proclaim photogravure “the most perfect of all photographic reproduction processes.” (1.)

The seed has been sown by this exhibition. May it bear rich fruit. Above all, it should convince those who still see artistic photography as a useless and pointless game that there is a deep and serious desire in amateur circles to raise photography to the status of art and to place it alongside other arts. – Franz Goerke, from the Preface: Nach der Natur (translated)

The folio is broken down in the following chronology: (all translated from German)

Opposite Title Page: (printed in red ink)

ALBUM ◦ DER INTERNATIONALEN

AUSSTELLUNG FÜR AMATEUR-PHO

TOGRAPHIE BERLIN 1896 ◦ HERAUS

GEGEBEN IM AUFTRAGE ◦ DER

DEUTSCHEN GESELLSCHAFT VON

FREUNDEN DER PHOTOGRAPHIE ◦

UND ◦ DER FREIEN PHOTOGRA

PHISCHEN VEREINIGUNG ◦ VON ◦

FRANZ GOERKE ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦

⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯

ALBUM ◦ OF THE INTERNATIONAL

EXHIBITION FOR AMATEUR PHOTOGRAPHY BERLIN 1896 ◦ PUBLISHED ON BEHALF OF ◦ THE

GERMAN SOCIETY OF FRIENDS OF PHOTOGRAPHY ◦

AND ◦ THE FREE PHOTOGRAPHIC ASSOCIATION ◦ BY ◦

FRANZ GOERKE ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦

Title Page:

NACH ◦ DER ◦ NATUR

PHOTOGRAVÜREN

NACH ◦ ORIGINAL-

AUFMAHMEN ◦ VON

AMATEURPHOTOGRAPHEN

BERLIN

PHOTOGRAPHISCHE

GESELLSCHAFT

⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯

AFTER ◦ NATURE

PHOTOGRAVURES

AFTER ◦ ORIGINAL PHOTOGRAPHS ◦ BY AMATEUR PHOTOGRAPHERS

BERLIN

PHOTOGRAPHIC SOCIETY

Dedication Page:

IHRER MAJESTÄT

DER KAISERIN UND KÖNIGIN

FRIEDRICH

IN TIEFSTER EHRFURCHT

ZUGEEIGNET

⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯

DEDICATED TO HER MAJESTY

THE EMPRESS AND QUEEN

FREDERICK

WITH DEEPEST RESPECT (2.)

Contents Page (Inhalt: p. 1/2)

Forward by FRANZ GOERKE.

Text by RICHARD STETTINER.

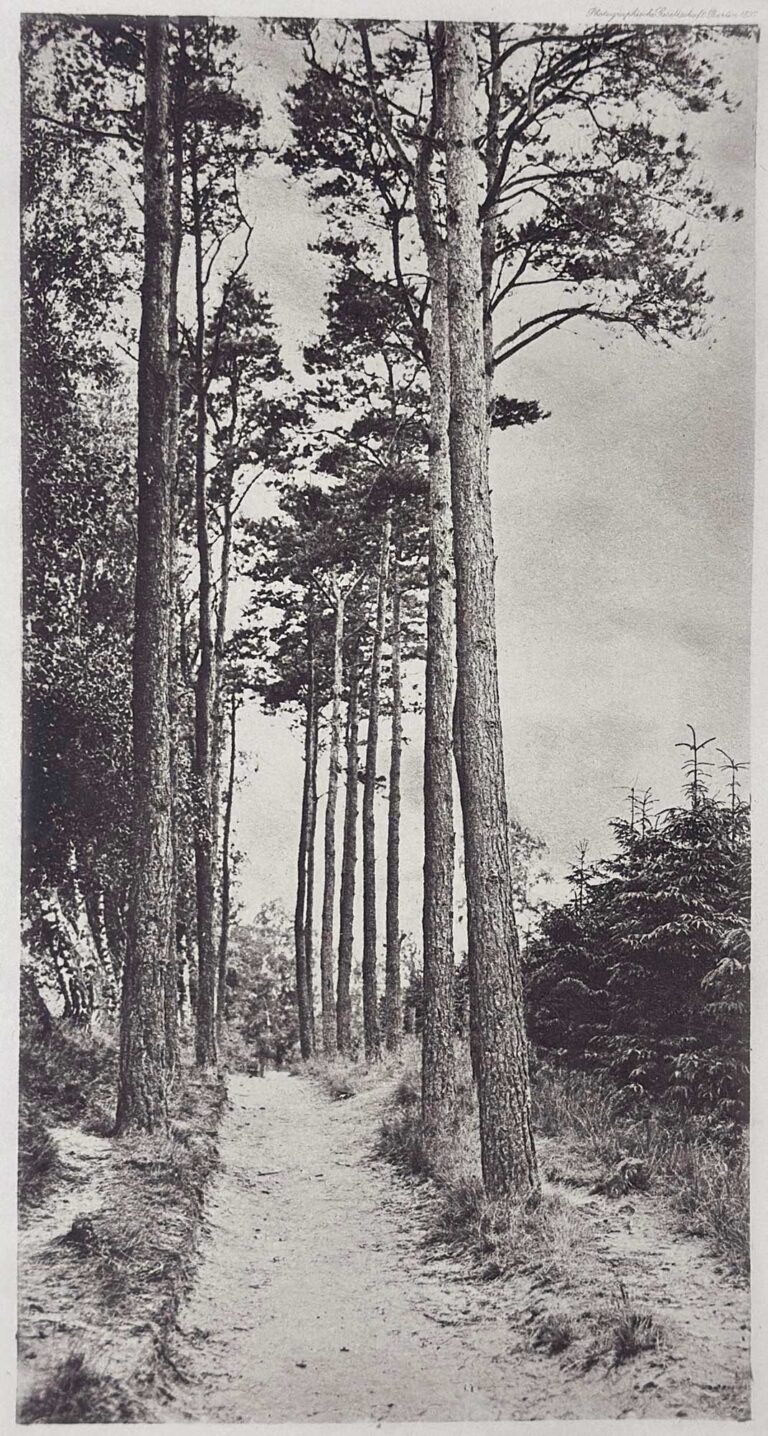

With paginated list of 7 photogravures reproduced within the text followed by 9 plates sequenced as photographer and title of work. (1-16) The individual letterpress leaves and folio plates within the entire folio are additionally preceded by protective glassine sheets imprinted with the respective name of photographer and title of work.

Contents Page (Inhalt: p. 2/2)

Continues: paginated list of plates 17-32 sequenced by photographer and title of work.

Forward (Vorwort) by Franz Goerke (p. 1/2)

If the present work, with which we are now presenting it to the public, gives us the opportunity to look back at the International Exhibition of Amateur Photography, we are all the more pleased because the Berlin amateurs are joining the ranks of those clubs for the first time that have made it their task to elevate amateur photography to the ranks of the arts.

The photographic clubs in Vienna, Paris and London have already occupied a leading position in amateur photography for years. And if Berlin can now for the first time stand alongside these leading clubs, we owe this primarily to Her Majesty the Empress and Queen Frederick, on whose initiative the exhibition was brought into being and whose energetic approach made it possible for the Berlin amateur clubs to organize it in the first place. In a joint meeting of the German Society of Friends of Photography and the Free Photographic Association, the following members of the associations were elected to the committee:

Prof. Dr. Gustav Fritsch, Geh. Medicinalrat, Franz Goemann, Franz Goerke, Alma Lessing, geb. Marschall von Bieberstein, Dr. A. Meydenbauer, Geheimer Baurat, Ernst Milster, Dr. med. Rich. Neuhauss, Marie Gräfin Oriola, Ludwig Russ, Dr. phil. Franz Schütt, Direktor Schultz-Hencke, Dr. phil. Richard Stettiner, Prof. Dr. Tobold, Geh. Sanitätsrat, Joh. Otto Treue, von Westernhagen, Major a. D., Dr. phil. Ludwig Wrede. | The committee was chaired by the senior medical officer Prof. Dr. Tobold, senior medical officer Prof. Dr. Fritsch and senior building officer Dr. Meydenbauer.

Forward (Vorwort) (p. 2/2)

Mr Schultz-Hercke and Dr L. Wrede were elected as secretaries, while the undersigned was responsible for setting up the exhibition. | Mr. Ludwig Russ took over the office of treasurer. | Mr Franz Goemann and Mr Joh. Otto Treue undertook the laborious task of setting up the exhibition objects.

In the present work, it is artistic photography that concerns us. From the rich material of the exhibition, we have tried to bring works of art that bear witness to the artistic direction and taste of today, and if we had to forego the reproduction of many important images.

The reasons are partly the difficulty of obtaining the originals, partly the limitations that any similar reproduction must impose on itself given the abundance of material.

But we believe that what has been presented is sufficient for an insight into the nature of our Exhibition.

The success of this exhibition has filled us with particular hope for the future. Not that we are already planning to repeat an exhibition of this size, but the idea has matured in the committee that the two Berlin amateur clubs should exhibit the most outstanding works from home and abroad in the field of artistic photography in a small salon every year. The seed has been sown by this exhibition. May it bear rich fruit. Above all, it should convince those who still see artistic photography as a useless and pointless game that there is a deep and serious desire in amateur circles to raise photography to the status of art and to place it alongside other arts. | In Brussels, the art of photography has been given a prominent place in the Royal Museum, and even though we are convinced that only through exceptionally favorable circumstances will the time come when we too will have such a place of care, where amateur photography can hope to be ranked among the arts, we are convinced that this dawn will one day dawn for our circles too. | But above all, this requires serious effort. | Germany in particular still has a lot to learn from other countries in this area. | The community of artist-photographers is still small here for the time being, but it too will train its disciples, it too will try to ensure that Germany will contribute through serious work to raising photography above the level of a mechanical process and to the importance that it rightly deserves in the artistic life of the nation. Franz Goerke

✻ ✻ ✻ ✻ ✻

Essay by Richard Stettiner

Last year a book was published: “The Struggle for New Art” by Carl Neumann, which caused a stir with its efforts to achieve an objective scientific understanding of modern controversial issues in the field of artistic creation. This book also touches on a question that is of great interest to anyone who is trying to think about the relationship between photography and art; “Art and Natural Science” is the title of a section of the work and it states the following: Historical criticism and scientific criticism play the most important role in modern intellectual life. Consequently, they have had the greatest influence on the visual arts. For natural science, the mediator of this influence is the photographic apparatus. “The more its use has spread, the more the scientific spirit of observation has advanced and pushed back the poetic-inventive spirit.” The author recognizes the benefit that photography can bring to the artist by enabling him to collect a wealth of study material. After a brief digression, the purpose of which is to demonstrate the inadequacy of the photographic image by the example that it cannot reproduce a movement motif in a generally understandable form, as is possible for the artist with the help of convention and combination, the author then comes to the core of his argument: “The great thing that we owe to photography, on the other hand, is that it has extraordinarily sharpened our powers of observation, that it ruthlessly exposes all the arbitrary actions of the drawing hand,” and now it is shown how, in contrast to the method of composition, an objective, one might say a scientific-artistic reproduction arises from photography, but “the moment one departs from the conventional composition-

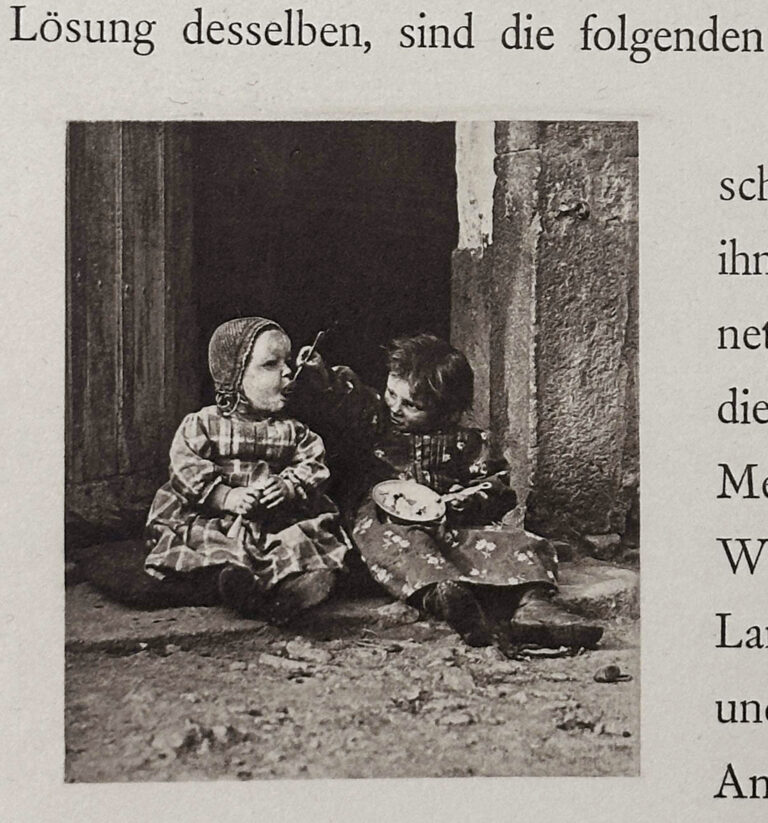

continues… with plate: FERDINAND COSTE, Lacanche, Cote d’or »Kindermahlzeit«. (Children’s Meal)

schema, there was a replacement for the abandoned accents of line in the accents of color and light.”

We leave Carl Neumann’s explanation here. What follows can be guessed by anyone who is not too far removed from modern artistic endeavors. Let us just give a hint: the first of the painters discussed following that line of thought is Max Liebermann.

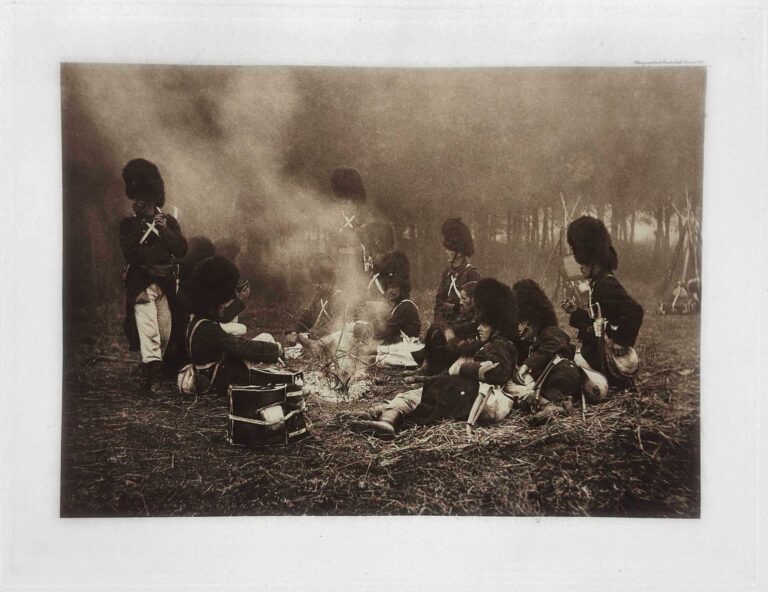

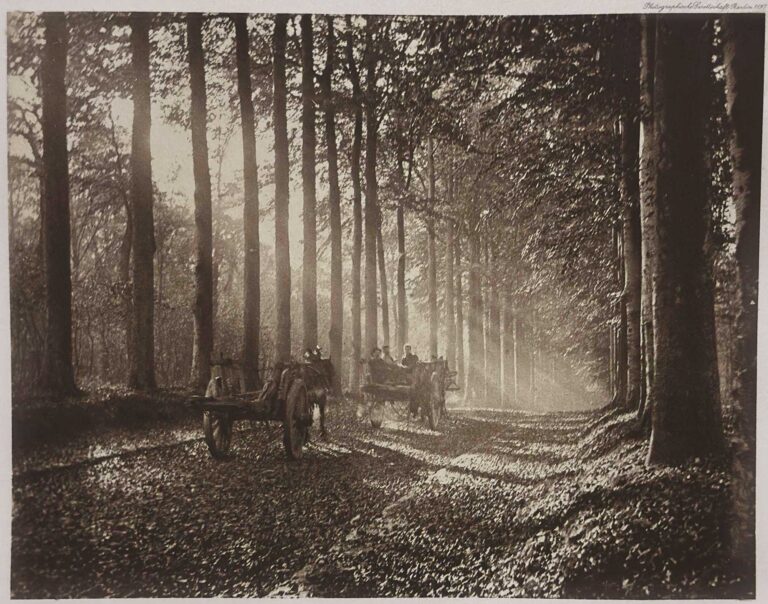

A few months after the publication of that book, the international amateur photography exhibition opened in Berlin. It showed to a wide circle of people what was already known to those more initiated who had visited the foreign or Hamburg exhibitions, that in the hands of numerous amateurs the photographic apparatus was no longer intended to reproduce the lines objectively and truthfully, but rather also strived to reproduce the accents of color and light or, better said in the case of black and white art, the accents of air and light.

Neumann would certainly not have changed anything in his deduction about the historical position of the photographic apparatus within our artistic development if he would have been aware of this highly interesting sidestream of modern art. But he would have expressed himself more cautiously when he spoke of the limits imposed on the photographic image in general, when he explained that it lacked precisely those qualities that today are the main aim of the most outstanding amateurs, the “artist photographers”; for here we are still faced with a problem. The following lines are devoted to illuminating this problem, not to solving it.

Initially, there was no other pretension in handling the photographic apparatus than to make it serve its objectively true character, as characterized by Neumann, in accordance with practical needs. The sole task was to capture the appearance of the people around us, the nature around us, in an objective manner. The landscape, for example, was only of interest as a view. Technique and taste were the requirements for the amateur – taste too, because in order to set up the apparatus in such a way that the desired image could be captured in a more

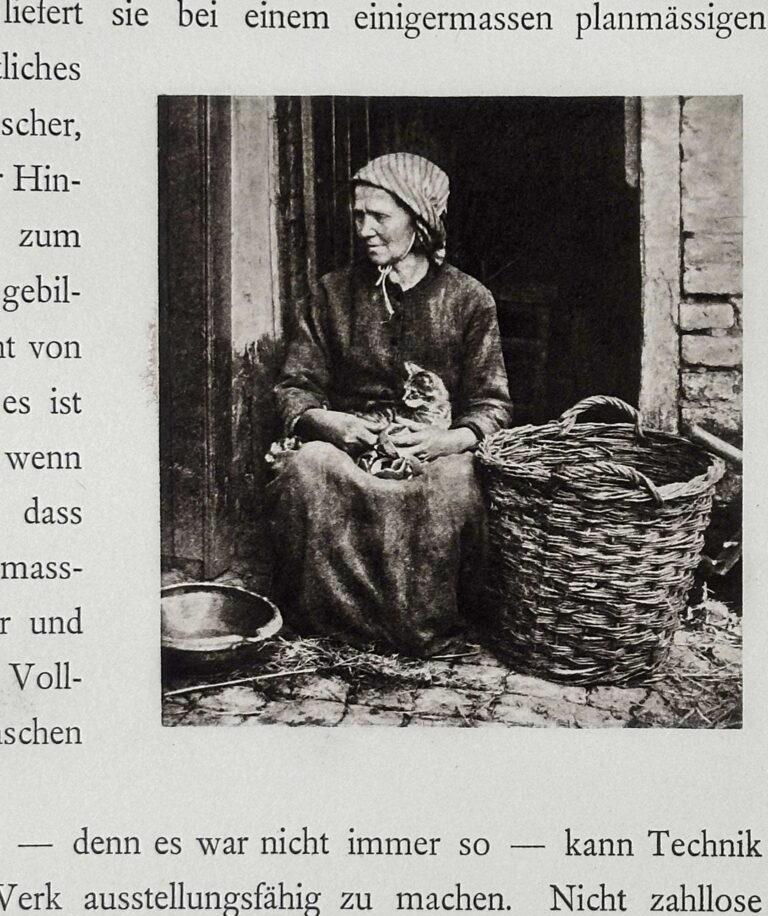

continues… with plate: JOH. F. J. HUYSSER, Overveen in Holland »Holländische Bäuerin«. (Dutch Farmer)

or less pictorially rounded form, without omitting anything important and yet avoiding anything disturbing, a certain, albeit not too high, development of taste had to be present. With a certain amount of enthusiasm, someone who was not completely untalented could manage to produce decent amateur photographs.

I would not think of describing such photography as a game in general. Moreover, if it is carried out in a somewhat systematic manner, it provides important scientific material in terms of cultural and art history, in terms of geography and ethnography, material whose value lies not least in the fact that it comes from educated and tasteful laymen, not from one-sided scholars. But it is clear that the game begins when one presents such material to one’s fellow human beings at exhibitions without any outstanding objective reasons being decisive, even today when with enthusiasm and leisure almost anyone can bring it to a certain level of perfection.

Today, of course today, because it was not always like this – technology alone is no longer enough to make a work suitable for exhibition. People do not want to see countless pictures in which the only significant variation is the signature, but rather works that bear the stamp of having been created by different personalities.

Only if such works exist do amateur exhibitions in the field of photography, apart from those for purely scientific purposes, have any justification. And they are justified today, because the desire to treat photography as a means of personal expression is there.

As a means of personal expression! Here lies a sharp contrast to what the photographic apparatus in the manner described above was for the general view until recently: a scientific instrument, used more or less skillfully by people. But to what extent is it actually

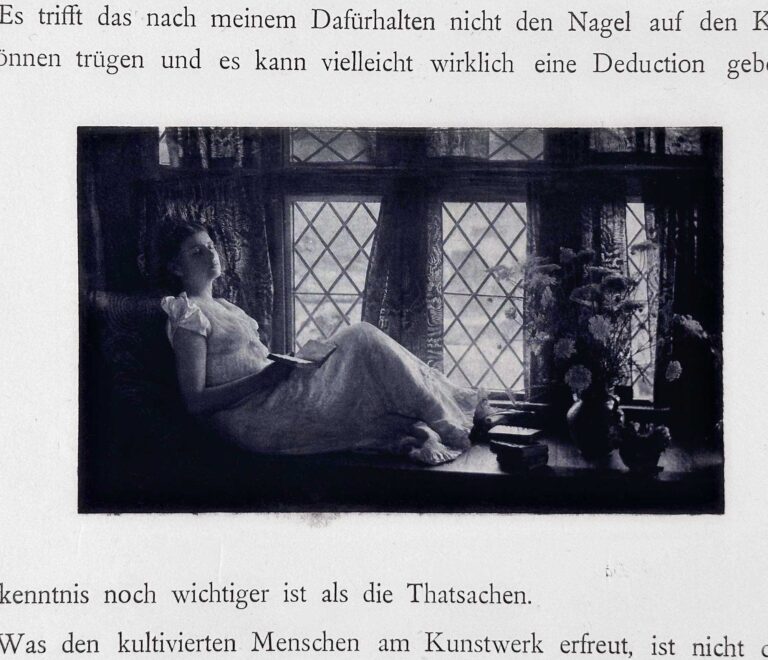

continues….With plate: E. J. FARNSWORTH, Albany, N.-Y. »ln der Dämmerung«. (At Dusk)

possible to use the photographic apparatus in that personal way, to use it to convey what one has personally seen in the picture? Raising this question, describing it as a problem, will only provoke an ironic smile in many people, who will point to the works of outstanding artist photographers and say: Just keep pondering, defining and deducing, and will always discover that you are outdone by the facts!

In my opinion, that does not hit the nail on the head. Facts can be deceptive and there may actually be a deduction that is even more important for our knowledge than the facts.

What cultured people enjoy about a work of art is not what is reproduced, the object or the content of the representation in itself, but the observation of the artist’s personal vision and the ability to reproduce what is seen in this way. Thus, on the one hand, the viewer takes pleasure in what he has seen and felt from the artist, and on the other hand, the pleasure in what he has done, which always instinctively contributes to our enjoyment of art. These two feelings are so intimately fused in our emotional life that we have so far hardly given any thought to the diversity of their nature. For skill was the only way in which the artist could communicate what he had personally seen to his fellow human beings, and Lessing’s Raphael without hands was just a poetic fantasy. I would like to say that even the appreciation of one of the two feelings, the pleasure in artistic skill, has not entered the consciousness of most people.

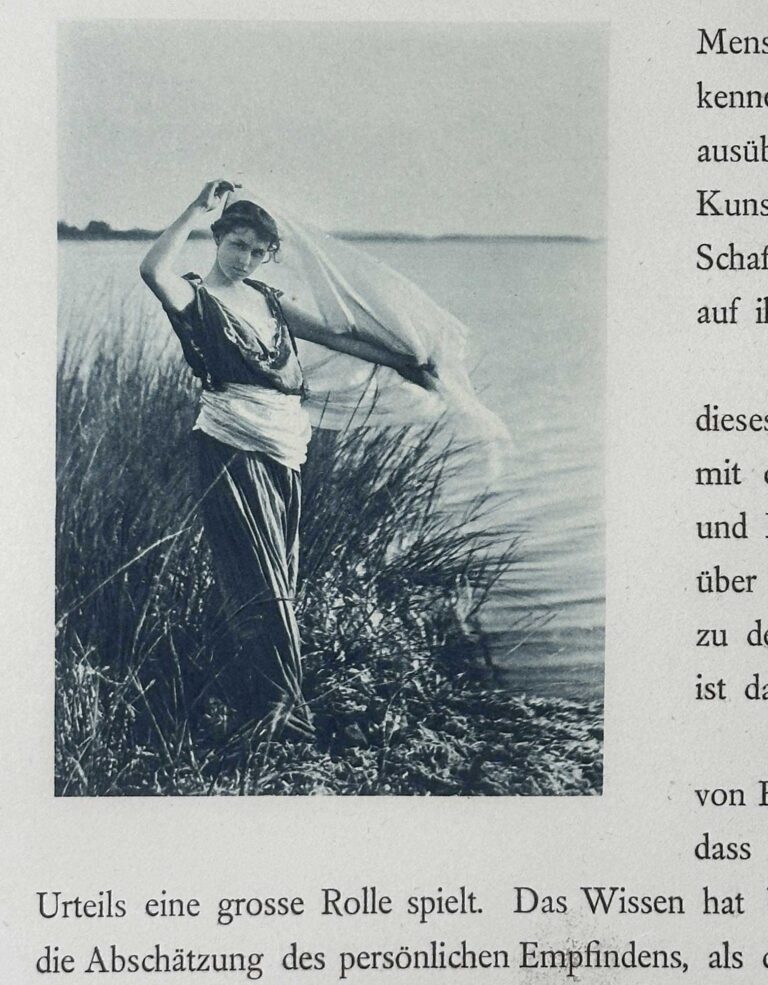

continues….With plate: E. J. FARNSWORTH, Albany, N.-Y., »Westwind«. (West wind)

People, but not all of them. For example, I know a sensitive, non-artistic lover who, when faced with good works of art, gets the feeling of his own creative ability. The skill in the work of art has such an uplifting effect on him.

It should be expressly noted that this feeling has absolutely nothing to do with the thirst for knowledge that inspires the artist and art researcher when it comes to a work of art, with the question that should only come secondarily to the enjoyment of art: How did this come about?

It is now also clear that we do not judge independently from case to case, but that our experience plays a major role in our judgment. Knowledge plays a much greater role in our enjoyment of art, both in terms of assessing personal feelings and ability, than many who strive for the appearance of great independence will admit. We admire this and that, which no longer seems admirable to us when we get to know the artistic environment from which it comes. This is clear when it comes to foreign art. A well-educated, art-loving person who, by chance, is not initiated into Japanese art will initially admire things that will then leave him cold when he has a more precise knowledge of them and a greater understanding of them.

In another case, I can imagine a cultivated person who has a fine understanding of modern art, but who, due to a chance lack of knowledge of art history that goes back a long way, initially remains completely incomprehensible when it comes to the primitive works of the Renaissance or even the works of Romanesque or Gothic artists.

In a roundabout way, I readily admit, in a somewhat complicated way, I have arrived at what I wanted to explain: When enjoying a work of art, admiration for the skill is one of the primary things, this admiration is based to a large extent on our knowledge, and so feelings of pleasure are instinctively aroused in us through analogy-

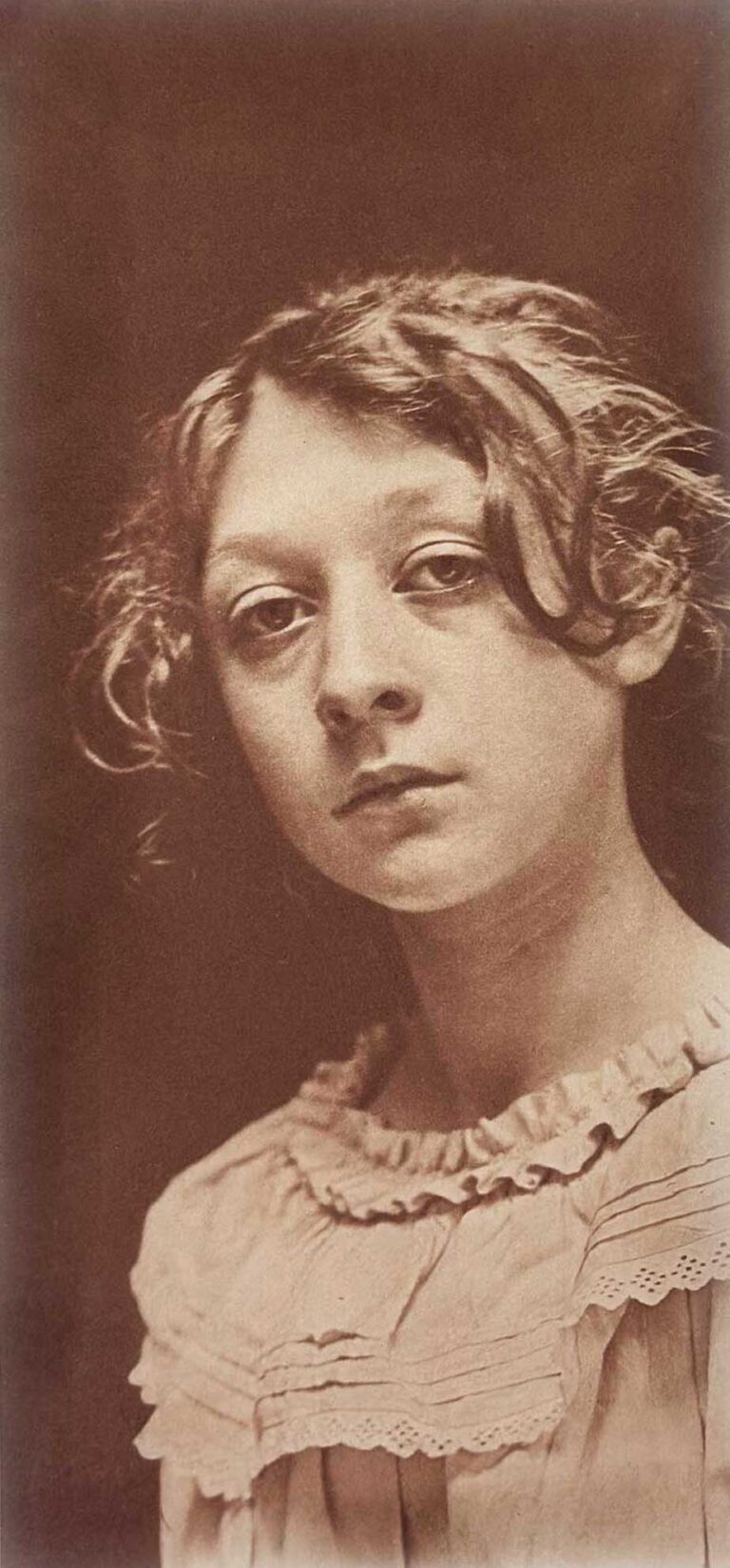

continues….With plate: DÉSIRÉ DE CLERCQ, Grammond, Belgien, »Die Fischerstochter«. (The Fisherman’s Daughter)

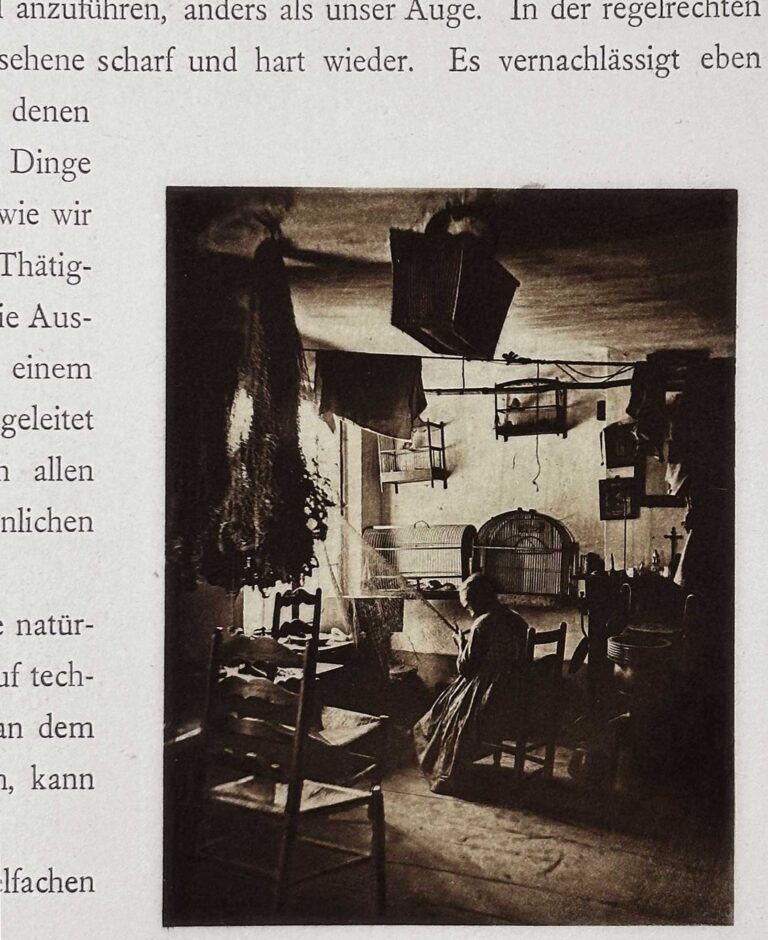

conclusions without us checking in detail in each individual case whether this analogy is justified. This is how we initially feel about the photographic work of art, where, deceived by the similarity of appearance, we ignore the way in which it came about, which deviates completely from the way in which everything that we have previously admired in the field of painting and black and white art came about. The skill contained in the photographic work of art is of a completely different nature and of a different value. The knowledge of this skill is the prerequisite for solving this problem, it is the prerequisite for a fair assessment, and finally it offers us the means of determining as such any transgression of the limits that are set for the art of photography by its own nature.

The artist photographer does not want to reproduce something of interest in terms of content in a more or less tastefully rounded but objectively true form, as the camera can provide if left to itself; rather, he wants to show us what he himself saw, not what his camera saw.

He wants to trigger in us through his image the same feeling that he himself had in front of the object. The apparatus presents difficulties.

The lens, to give an example, sees differently than our eyes. Used correctly, it reproduces what is seen sharply and harshly. It neglects precisely those light and air accents that were mentioned above; it reproduces things as we know them, not as we see them. Thus the artistic activity that lies before the photograph, the selection of the object, no matter how sensitively it is guided by a sense of sensitivity, is destroyed by a photograph taken according to all the rules of art in the usual sense.

At this point I can of course only express myself in general terms. I cannot go into technical details, which would not change the overall picture.

continues….With plate: JOH. A. BAKHUIS, Olst in Holland, »Portratstudie«. (Portrait Study)

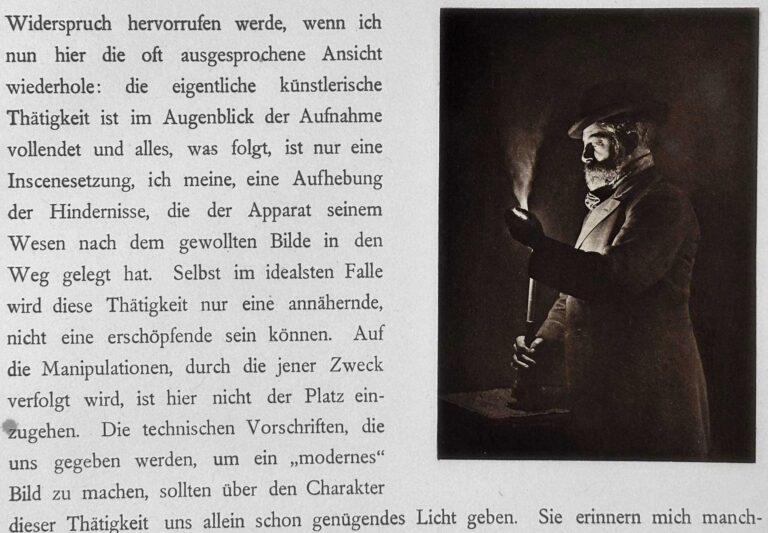

I will not provoke any controversy if I now repeat here the often expressed view: that the actual artistic activity is completed at the moment of the recording and everything that follows is only a setting, I mean a removal of the obstacles that the apparatus, by its very nature, has placed in the way of the desired image. Even in the most ideal case, this activity can only be approximate, not exhaustive. This is not the place to discuss the manipulations by which this aim is pursued. The technical instructions that we are given to make a “modern” picture should alone give us sufficient light on the nature of this activity. They sometimes remind me of a painting textbook from the last century: to paint a corpse of Christ, use these and these colors. Reproducing what has been seen artistically in a tasteful form is therefore the task of the artist photographer. A broad and fertile area that will always have its audience as long as artistic vision is not pushed into the background by technical tricks, as long as the actual artistic activity does not disappear behind the setting. In our work, reproduction has generally been based on the photographic plate itself. This has a certain programmatic significance, and one can see that the result is not a bad one, although of course those who want the print, the end result of the photographic activity, to be the basis of the reproduction have a justification for their view. Amateur art is a term that is difficult to define with any certainty, but in general we understand it to mean that practice of art which, without the support of professional training, is still groping in its ability, but strives to give expression to artistic sensibility.

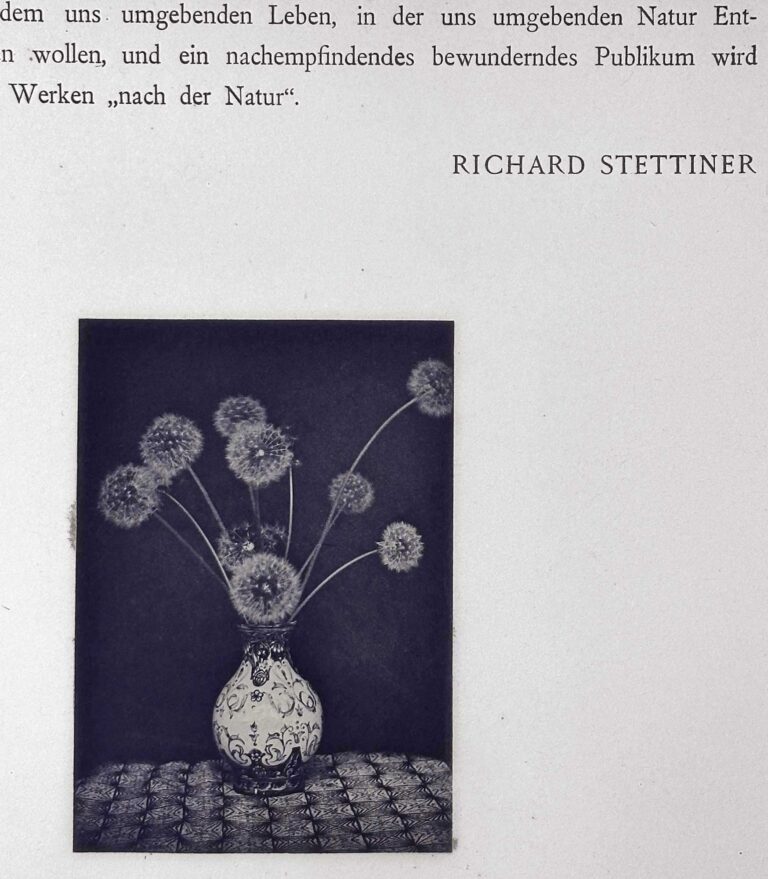

continues….With plate: ALEXE GRAHL, Loschwitz bei Dresden, »Blumenvase«. (Flower Vase)

Is amateur photography really an amateur art in the common sense?

The men who are in the front rows here differ from the professional man, in terms of the extent of their activity, only in that they do it for its own sake, not for profit. In terms of technical experience and technical ability, they are usually superior to him… and yet, amateur photography is an amateur art, it is even the true amateur art. Because true artistic “ability” is excluded by its nature, the entire emphasis is on the side of artistic seeing and feeling, of artistic intelligence, I would say. As long as amateur photography stays within its limits, it will have followers among those who want to make discoveries with a sensitive sense in the life and nature that surrounds us, and an empathetic, admiring public will not be lacking for these works based on nature.

RICHARD STETTINER

✻ ✻ ✻ ✻ ✻

Contemporary Account: 1896 International Exhibition for Amateur Photography in Berlin.

On September 3rd, the international exhibition for amateur photography opened in the new Reichstag building. The choice of location is certainly a very fortunate one, because as a sight in Berlin, it already exerts a certain attraction on the public. The rooms made available for the photography exhibition are on the first floor and are large enough to be able to arrange the numerous pictures etc. received in a clear order. Unfortunately, the lighting conditions are sometimes quite unfavorable, so that some beautiful pieces do not really come into their own. The exhibition itself is richly represented by all parts of the world, namely Austria, England, France and Belgium, which are countries that have participated heavily and are distinguished by their outstanding achievements, especially in artistic terms. While the landscape and genre pictures of German amateurs are mostly made on the now modern celloidin and platinum paper, the Austrians, English and French have chosen copying methods more in line with their subject matter and thereby increased the effect of the pictures, so that some pictures can be considered true works of art. In order to give a complete picture of photography and its application, the factories of apparatus and chemical preparations, as well as the renowned institutes for photomechanical printing processes, have also been invited to the exhibition; furthermore, the exhibits of Dr. Jagor and J. B. Obernetter will show us a series of interesting historical pictures.

The different groups into which the exhibition is divided are: application of photography for scientific purposes (astronomy, meteorology, medicine, microphotography, X-ray photography, spectral analysis, etc.), application of photography in art history and arts and crafts, landscape, portrait and genre pictures, photomechanical printing processes, apparatus and chemical preparations, specialist literature. There are a total of around 580 exhibitors. If we enter the exhibition from Portal II of the Reichstag building, we first come to the section for landscape, portrait, etc.

For a large part of the landscapes, a description of the subject is missing and the pictures naturally lose interest if the viewer does not know the subject in person or the pictures do not have a special painterly charm or a remarkable technique. The fact that there are also some mediocre pictures among the many on display is something that comes with every exhibition; we will essentially limit ourselves to describing the more outstanding items and begin with the group of landscape, portrait and genre pictures. (3.)

Review of Nach der Natur in Bulletin du Photo-Club de Paris

The Album Nach der Natur, published following the International Exhibition held last year in Berlin, Germany, consists of thirty-two plates in photogravure printed on beautiful paper measuring 50 X 37 centimeters. The care taken in the execution of these plates and the choice of the works reproduced make it a document of the highest interest, and of great artistic value for all those who are interested in the progress of photographic art. We sincerely congratulate Mr. Goerke and Stettiner, the authors of this splendid publication. (4.)

✻ ✻ ✻ ✻ ✻

21st Century Analysis

Christian Joschke, professor of art history at the Beaux-Art De Paris, describes the cultural and political forces leading up to the 1896 Berlin exhibition- touching on the publication of Nach der Natur for his 2013 volume: The Eyes of the Nation. Amateur photography and society in the Germany of William II. (Dijon, Presses du Réel, 2013) The culmination of his 2005 Doctoral Thesis/Dissertation at the University of Mannheim, he outlines some of these forces shaping the 1896 exhibition: (translated)

The situation was different in Berlin, and allows us to better understand the links that forge science and politics in the visual culture of North Germany. The liberal Berlin elite, composed of industrial barons, astronomers and biologists, all fascinated by the resources of photography, became aware of the potential of these amateur clubs at the Hamburg exhibition. They understood then that photography would constitute the point from which it would be possible to modify not only the relationship to science, but to create a visual culture of “enlightened men”, which encompasses the arts and sciences. This elite concretized, with the exhibition organized at the Reichstag in 1896, the project of a relationship to images radically different from the fascination that the Berlin population then felt in front of the multiplication of shows and images of all kinds, an “enlightened” relationship to visual culture. And this project took on an eminently political meaning, in a city divided by the violent competition between the central power of William II and the local power of the declining liberals. (5.)

With the 1896 exhibition, he sought to exhibit the coherence of a common visual culture, the porosity of the boundaries between the fields of application of photography. The catalogue prefaced by Fritsch and Goerke contained mainly, as we have said, scientific texts. But Goerke also published a valuable folio, Nach der Natur (From Nature), bringing together a selection of the most beautiful photographs exhibited, in the most faithful pictorialist style. In the text accompanying this catalogue, Richard Stettiner developed arguments on photographic aesthetics. (6.)

The album entitled Nach der Natur (From Nature)80, already mentioned, reproduced the best amateur photographs presented at the 1896 exhibition (fig. VII/2). Richard Stettiner, who wrote the texts, underlines the aspiration, according to him legitimate, of photography to become an art in its own right. Although this text is certainly not included in the exhibition guide booklet and tends to treat artistic photography as an activity separate from scientific imagery, its arguments nevertheless reveal the deep links woven, in the Berlin context, between art and science. The juxtaposition of two types of imagery in the same network of clubs and in the same place – the Reichstag – was coupled with a real theoretical hybridization. The cohesion of a common culture of realities seemed to be revealed in the echo given by aesthetic discourse to the arguments of science. In this album, Richard Stettiner attempts to free photography from its role as an artistic document. Photography is not, in his eyes, a tool offered only to painters for the study of nature, but it also aspires to become an art. For it does not only serve to reproduce with exactitude the image of nature, but it is also a “means of personal expression” {persönliches Ausdrucksmittel) expressing better than any other art a personal view cast on nature. It would thus be a privileged means to express the Können (power, potentiality) of the artist, the very principle of art (81). (7.)

✻ ✻ ✻ ✻ ✻

Franz Goerke: 1856-1931

Franz Goerke was an important exponent of German art photography who went on to be editor and publisher of Die Kunst in der Photographie (The Art in Photography) from 1897-1908. Born on November 14, 1856 in the former German city of Königsberg, (now Kaliningrad) he received his original training in banking, but was apparently inclined to devote himself to more general studies. He photographed as a hobby, and in October 1889 he founded, together with 52 other members, the “Free Photographic Association” in Berlin, in which he accepted the office of Recorder. Goerke was president of the association from 1912-1919. Yearly compiled volumes of Die Kunst in der Photographie can be viewed on this website, beginning with the 1897 folio.

Prof. Dr. Richard Stettiner: 1865-1927

Biography from Obituary (translated): Richard Stettiner was born on May 12, 1865 in Berlin, attended the Friedrichsgymnasium in Berlin from 1874 to 1882, the Wilhelmsgymnasium in Eberswalde until 1884 and passed the school leaving examination here at Easter 1884. In 1884 he first devoted himself to studying modern art history, archaeology and history in Berlin, in 1885 in Bonn and from 1883 to 1889 in Strasbourg. He received his doctorate from the University of Strasbourg on August 1, 1889, then worked as a voluntary assistant at the museums in Berlin in 1891 and 1892 and as a scientific assistant at the Museum of Art and Crafts in Hamburg from February 1, 1900. From August 3, 1900, Stettiner was a citizen of Hamburg, and a professor from December 1, 1909.

On December 15, 1927, the Hamburg monument conservator Professor Dr. Richard Stettiner died in Ebenhausen in Upper Bavaria at the age of 63. His passing has had a serious impact on the preservation of natural monuments, because Stettiner, whose work was primarily dedicated to the preservation of art, had also taken on the preservation of nature in his official position with care and understanding and had proven himself to be one of its most reliable pillars. He was in constant contact and exchange of ideas with the State Office for the Preservation of Natural Monuments in Prussia. (8.)

✻ ✻ ✻ ✻ ✻

Notes:

1. Stieglitz, “Reviews and Exchanges: ‘Nach der Natur’,” Camera Notes 1 (January 1898), 85. Extract: Stieglitz’s Portfolios and Other Published Photographs, Julia Thompson: 2002: Alfred Stieglitz: The Key Set, p. 936, vol. 2.

2. Victoria Adelaide Mary Louisa, Princess of Great Britain and Ireland VA , from 1888 Empress Frederick (* 21 November 1840 in Buckingham Palace , London ; † 5 August 1901 in Friedrichshof Palace , Kronberg im Taunus ), was the first child of Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha and Queen Victoria of Great Britain and a British Princess Royal from the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha . As the wife of Frederick III, she was Queen of Prussia and German Empress in 1888 and mother of Kaiser Wilhelm II. -Wikipedia (2024)

3. Excerpt: International Exhibition for Amateur Photography in Berlin, by Paul Hanneke: Photographische Mitteilungen: October, 1896: pp. 205-209/ Continues: pp. 219-224; 235-37.

4. Bibliographie: Bulletin du Photo-Club de Paris: October, 1897: p. 344

5. Christian Joschke: Excerpt: VII: Les arts à l’aune des sciences : construire une culture visuelle globale à Berlin en 1896: Les yeux de la nation Photographie amateur et société dans l’Allemagne de Guillaume II: 2005 Doctoral Thesis/Dissertation, University of Mannheim: p. 172

6. Excerpt: 5. L’habitus savant et l’espace public : la carrière de Franz Goerke: Ibid: p. 205

7. Excerpt: 7. Art et science : l’album de Goerke et Stettiner: Ibid: p. 213

8. IX. Personnel message: Richard Stettiner ♰ : Der Naturforscher, Berlin: February, 1928: p. 576