Picturesque Bits of New York And Other Studies

Picturesque Bits of New York And Other Studies: work by an American published in America

The publication of the portfolio Picturesque Bits of New York And Other Studies by Alfred Stieglitz in 1897 was the culmination of many things for Stieglitz, but perhaps most importantly, it was an emphatic statement that photographs by an American by birth finally mattered in the overall larger context of pictorial photography first established in England and Continental Europe beginning in the early 1890’s. This movement, witnessed firsthand by Stieglitz while he was still living in Berlin and later upon returning to the United States after 1890, coalesced with the first international photographic art exhibition in Vienna in 1891, in which he was invited to exhibit work. A magnificent limited edition portfolio of large plate heliogravures (hand-pulled photogravures), was issued by the exhibit committee for Vienna, and later collected by Stieglitz in his personal photographic library back in New York. Later international exhibits in which Stieglitz participated in and was represented by his own photographs published in elaborate, limited edition photogravure portfolios included the first Photo Club de Paris exhibits beginning in 1894 and the English Linked Ring folios first issued beginning in 1895. Many of these photographic portfolios can be seen in their entirety on PhotoSeed.

Basis & Intent in route to a capstone achievement

The basis and intent for this portfolio: fine photographic engraving, had already been in Stieglitz’s blood by the time Picturesque Bits made its’ 1897 appearance. In 1890, upon his return to America, Alfred’s father Edward Stieglitz made it financially possible for his son to become a partner in the Heliochrome Company, which specialized in photo-engraving. Later renamed the Photochrome Engraving Company, Stieglitz resolved himself to make his own mark with perfecting the nascent craft of photoengraving in America, with an emphasis on perfecting the photogravure process.

Soon, publishing, editing and writing were keystones for Stieglitz’s progression in the 1890’s, with his larger aim of promoting the acceptance of artistic photography in America. Calling it a fight and aided with a healthy trust fund provided by his father, Stieglitz took on roles including editorship of The American Amateur Photographer (1895) and the founding and editorship of Camera Notes in 1897. An entirely original publication and organ of The New York Camera Club, Camera Notes featured several stunning photogravure plates as part of each quarterly issue. Photogravure was at the forefront of his later publishing ventures, with the debut of Camera Work in 1903 and concluding in 1917.

Empowered by this experience, Stieglitz teamed up in 1897 with the New York City-based publisher Robert Howard Russell, a highly regarded publisher of fine art publications, and issued his first portfolio of large-plate photogravures.

The title of his portfolio: Picturesque Bits of New York And Other Studies, is deliberately geared to emphasizing Stieglitz’s New York images, with the title page of the portfolio employing red ink to accentuate the Picturesque Bits of New York aspect of the overall work in the letterpress. Truth be told, only four of the dozen images featured New York scenes, the others being photographic studies done in Paris, Venice, Holland and Germany.

Soon, glowing reviews of the work appeared, notably in 1898 by the lone Camera Notes publications committee member and editorial associate William M. Murray. A less favorable but nonetheless respectable estimation of the portfolio was included with a profile done on Stieglitz in mid 1898 by the well-known art critic Sadakichi Hartmann. Both are included here after this introduction.

A modern view of the portfolio by author and critic Alan Trachtenberg appeared in 1989:

“The picturesque gave unity to Stieglitz’s pictures, a group of which he issued in 1898 in a portfolio of twelve gravures as Picturesque Bits of New York and Other Studies. Combining New York scenes with those of Venice and Paris, of canals and boulevards, the portfolio makes the argument that New York is equally worthy of artistic treatment, equally beautiful. The pictures vibrate with atmosphere–fog, snow, streetlights reflected on wet pavements. The word “bits” suggests fleeting impressions caught by a highly selective eye, the crystallization of experience similar to the effects sought by Ezra Pound and Hilda Doolittle in the Imagistic poetry they would invent in the next decade.” 1.

A two-page advertisement for the portfolio appeared in a small catalogue issued by publisher RH Russell in 1897 stating specifics for the portfolio as well as photographs, which Stieglitz sold individually. An excerpt:

“The twelve subjects, together with an introduction by W.E. Woodbury, are issued in an artistic portfolio. Price, $10.00

There will also be an Edition-De-Luxe in a special binding, limited to forty copies of the first impressions, each plate signed by Mr. Stieglitz. Price, $25.00

Single Proofs of any of the plates. Price, $2.00, each.

Artist’s Proofs, signed by Mr. Stieglitz. Price, $5.00, each.” 2.

Even with this marketing push by RH Russell as well as others, it is doubtful that many of the Picturesque Bits portfolios were sold, especially the $25.00 Edition-De-Luxe edition signed by Stieglitz. Book seller catalogues around the turn of the 20th century remaindered original $10.00 “ordinary” copies of the portfolio to $5.00. The now accepted total copies of this seminal portfolio in the history of photography numbers a mere 25 copies:

“The photogravures were printed in an edition of twenty-five on plate paper using different ink colors.” 3.

A small but important sampling of some of the key original plates from the Picturesque Bits portfolio is included with this overview.

Notes:

1. Reading American photographs: Images as History: Mathew Brady to Walker Evans : Alan Trachtenberg: 1989: Hill and Wang: New York: p. 184

2. Books & Artistic Publications: R.H. Russell: 33 Rose Street, New York: 1897

3. Alfred Stieglitz | The Key Set: The Alfred Stieglitz Collection of Photographs: Volume Two 1923-1937: Sarah Greenough: National Gallery of Art, Washington| Harry N. Abrams, Inc. : 2002: p. 937

1898 Camera Notes review of the portfolio by William M. Murray

Reviews and Exchanges.

Picturesque Bits of New York, and Other Studies. By Alfred Stieglitz. A Portfolio of 12 photogravures, on paper 14×17, with an introduction by W.E. Woodbury. Published by R.H. Russell, New York. Price $10.00

“Picturesque Bits of New York and Other Studies” is the title of a new art publication by Robert Howell (sic) Russell, New York, a publisher of high-class illustrated books. It is a portfolio containing 12 art studies by Alfred Stieglitz, reproduced in photogravure from the original photographs, and takes a worthy place in a series of similar publications by Mr. Russell, for which he engaged the services of no less eminent artists than William Nicholson, Charles Dana Gibson, Frederic Remington, A.B. Wenzell and Edwin A. Abbey. The subjects of these studies by Mr. Stieglitz are all familiar to the members of the Camera Club, especially to those who attend the Wednesday night tests and informal reunions, and need no extended notice at our hands. They include “Winter on Fifth Avenue,” “A Venetian Canal,” “A Winter Sky,” “A Wet Day on the Boulevard,” “Reflections, Night,” “On the Seine,” “The Glow of Night,” “The Incoming Boat,” “The Old Mill,” “Scurrying Home,” “The Letter Box,” and “Reflections, Venice.” Most of these studies are famous prize winners, having received high awards in America, England, continental Europe and far off India, and copies of several of them have been sought at prices that would not be deemed inadequate for an oil painting of the same subject. It is a privilege, therefore, to be able to obtain, at a very reasonable sum, these dozen admirable pictures. We have been accustomed to see the fine tones and graduations of our best workers so utterly ruined in the process of engraving and printing that we are agreeably surprised at the wonderful delicacy and transparency of these examples. They are printed on heavy plate paper, 14×17 inches, and each plate is presented in a color appropriate to the subject. We might take exception to the tint employed in the “Glow of Night,” where the desire to reproduce the yellow glare of the incandescent and other lights glowing through the fog and mist of a rainy night on Fifth Avenue has led to the employment of colors that are singularly disagreeable. Perhaps our photographic experience heightens this repugnance, because the tones, ranging from yellow to a somewhat dirty greenish black, recall the effect of an aristotype badly sulphurized in a combined toning and fixing bath. It is possible that the print will be more satisfactory to an artist, or to an art lover, who has never dabbled in photography. In all the other cases the colors are admirably chosen. The first of the series, “Winter on Fifth Avenue,” is undoubtedly the finest reproduction of the set. We may say truly that in this case there is absolutely nothing lost of the finest gradations of the original. The driving sleet and the uncomfortable atmosphere of the wintry day are as perfectly reproduced as in the wonderful little 4×5 plate from which so many enlargements have been made since Mr. Stieglitz first made the snap-shot with a borrowed detective camera. It was, at the time, deemed a “lucky hit” by his fellow members in the club, but these lucky hits have since followed each other so fast that the angel of success is now believed to attend Mr. Stieglitz in all his photographic undertakings. The name of this angel, however, according to Mr. Stieglitz himself, is “Patience.” This very picture, taken at a time when he did not believe in instantaneous photography, was only secured after a three hours wait in a blinding snow storm, on Washington’s birthday in 1893. Nor is patience all that is necessary. Many men, possessed of artistic perceptions and ambitions, have attempted effects as charming as this, and failed, simply because they lacked the technical skill to record the scene. Many of us have photographed snow and rain, and yet found no sign of the falling rain or driving snow on the negative after development. How, then, did Mr. Stieglitz obtain this result, which is here so evident even after all the intervening processes from photographic plate to finished steel engraving? It is not merely that he is an artist, with an eye ever watchful for pictures as they present themselves in the ordinary scenes of human life, but that he is a skilled photographer as well, full of the resources that a long training in the laboratory gives him for all the chemical and mechanical processes of what has been well called, the art-science. Mr. Stieglitz has been, since his first initiation into our organization, a leader in the scientific as well as the art side of photography, and most of the new processes of printing, and toning, and other means of more perfectly reproducing pictorial values have been introduced to us by him in both precept and example. And the singular perfection of these 12 art studies is due principally to the fact that the diapositives from which the steel engravings were taken were made by Mr. Stieglitz himself, rapid plates being used, so as to preserve to the fullest extent the detail and softness of the originals, and that every print has been produced under his critical supervision. A copy of this artistic publication has been added to the club library. W. M. M. 1.

1. Reviews and Exchanges: William M. Murray: in: Camera Notes: Vol. 1, No. 3: January, 1898: Published Quarterly by the Camera Club, N.Y. : New York: pp. 84-85

note: Murray, a member of the New York Camera Club, was the lone publications committee member for Camera Notes and an editorial associate for the magazine.

Sadakichi Hartmann: Excerpt: An Art Critic's estimate of Alfred Stieglitz –1898

Alfred Stieglitz has recently for the first time given the general public an opportunity to estimate his work by letting the publishing firm of R. H. Russell reproduce twelve of his original photographs in photogravure (“Picturesque Bits of New York and other Studies “).

We have seen so many paintings and illustrations that look like photographs, that it is refreshing to see once photographs that look somewhat like paintings.

Although I am aware that I cannot do perfect justice to Mr. Stieglitz by criticizing the contents of this map—realizing fully how much is lost by the process of reproduction—it will after all be more advisable than to criticize the originals themselves, of which only two or three perfect copies are in existence and which but few will have an opportunity to study.

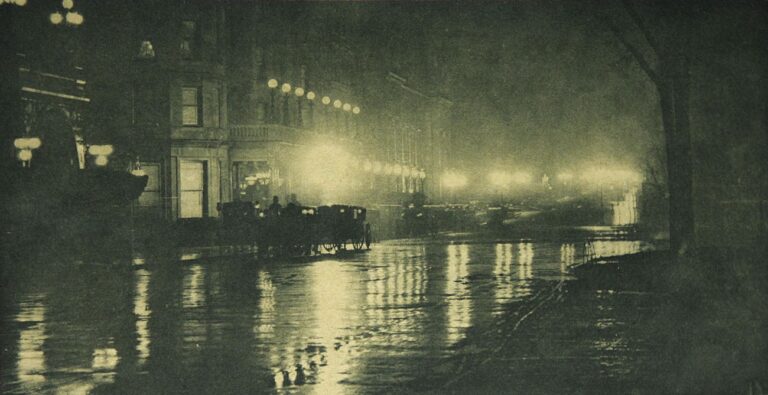

The map contains two complete failures: “The Incoming Boat,” which is in every respect commonplace, and “The Glow of Night,” Fifth Avenue with a full view of the Savoy with its long rows of lighted candelabra reflected on the wet pavement, which is utterly spoiled by the attempt of lending it a color effect, a cheap yellow monotony which has robbed the otherwise excellent picture of all its delicacy and vibratory force. Reproductions of works of art are always most dignified in black, or at least one dark tonal color.

“The Old Mill,” a picturesque nook somewhere in the Black Forest, is one of those bits of realism that become romantic not so much by the handling of the artist, but by the reminiscences that such old landmarks awaken in us. It shows competent composition and exquisite gradation of light and shade, strong and powerful in the foreground, and fragile in the remoter parts.

Also “The Letter Box,” two little barefoot peasant girls in their neat Badenser costume, depositing a letter, with the diagonal wall of a house as background is merely a genre study, an attempt at story telling that arouses no special interest. Also other men could do it and I am only interested in that part of a man’s work which the majority would find rather difficult to perform.

Of the two studies of Venice the reflections in the canal of the one termed “Reflections” are entirely too harsh in outline and values to allow a satisfactory enjoyment. The water is too opaque and has lost in parts all power to convey fluidity. It seems to be one of the most difficult tasks to photograph reflections in a sheet of water, as nearly all attempts at it seem exaggerated and untrue to me. That the difficulties, however, can be overcome, ‘Stieglitz shows in his “Bit of Venice.” A stretch of water of a canal as foreground, losing its perspective in its gondola-lined embankments of quaint weather-stained house walls with a bridge and the suggestion of another cross-thoroughfare as background. The texture of the reflection is superb, mellow, blurred, and of manifold variation, only where the sky is mirrored in the foreground a delicate tint is lost which lends a special charm to the original. The composition of the upper part is perfect. It gives a better idea of Venice than many a painting. It conveys the true spirit of Venice, that poetical city of “broken fragments and washed out colors” that reflects in its quaint melancholy the history of a sumptuous past.

In his “Wet Day on the Boulevard,” the photographer has attempted figure composition on a large scale. Although not quite satisfactory from a painter”s viewpoint, it has many excellent qualities. The empty foreground, the store in the left hand corner, and in particular, the hazy vista of the boulevard with its cabs, is worthy of a de Nittis. The only potent criticism I have to make is that the pedestrians coming towards us crossing the street, lift their feet in a way that does not seem natural, although instantaneous photography has proven beyond dispute the correctness of such fugitive movements. The problem is whether we are not accustomed enough to the representation of such instantaneous reality to discover any beauty in it, or whether there is no beauty in the scientific analysis of movements, the details of which our eyes are not capable to report. More characteristic pedestrians, a grisette daintily lifting her skirts, or some other more typical type of the boulevards would have probably improve the picture.

The rotunda at Fifth Avenue and Fifty-ninth Street, with the Savoy and New Netherlands Hotels as backgrounds, is a bold attempt at night photography. The effect is very beautiful, but at closer scrutiny one finds the blacks rather monotonous, in particular, the defoliated branches of the trees which form a confused network that disturbs. A special compliment has to be paid, however, to the photographer for discovering for art one of the most picturesque spots of nocturnal New York. I do not know a single painting in recent exhibitions that attempts a similar subject with equal grasp of pictorial beauty. It is a lesson to our painters that cannot be undervalued.

A “Winter Sky,” a solitary fir tree, on a snow-covered hill with the sun struggling through a cloudy veil and glistening on the ice-crusted branches. Stieglitz has tried himself as a virtuoso. The effect is remarkable, but is too near the border line of sensationalism to be considered a work of art.

Now we come to the three last pictures— “On the Seine,” “Scurrying Home,” and a “Winter Day.” They are, with his “Net Mender,” (not in this collection) a young girl sitting on the dunes mending her nets, a simple poem of nature like a canvas of Lieberman—the masterpieces of his career. Before them criticism necessarily grows silent or becomes largely descriptive, as it always does when art approaches perfection. On the Seine, a double road on the embankment of the river, with a row of trees in the middle, loses itself in an obtuse angle in the distance. A flock of goats has grouped itself in the road nearest to the river. To the right a vista on the Seine, a tug boat with a line of barges, and a silhouette of the housetops of Paris in the distance. It is a decorative panel filled with the musical cadence of a waning day, and that peculiar atmosphere which roads where city and country blend together always have for me. What patience the artist must have exercised before the goats grouped themselves so adequately! In fact Mr. Stieglitz told me that for more than a week he stood every afternoon at dusk with his camera at the same spot, until at last he saw before him what he considered essential for a picture. The cluster of dark foliage, the border of grass along the edge of the water, and the distance have lost in values through the reproduction, but otherwise it is a picture which any modern master could be proud of. It is a well balanced artistic composition of rare decorative suggestiveness which shows that the artist understands the charm and power of linear and spacial beauty. “On the Seine” is a tribute to the undeniable truth that the future of art lies largely in decoration.

“Scurrying Home ” could teach many an artist what composition means. It is more simple and direct than the previous picture. Two Dutch women crossing an open waste of sand, with the Katwyk Church, made famous by modern painters, in the distance. How interesting the texture of the foreground! How well its oblique lines cut those of the middle distance! How well the distance is managed! And how marvelously the figures are placed, considering that if they had been photographed one second sooner or later the picture would have been spoiled. Their movement is as natural as it can be; it suggests the breeziness of the weather; only the feet of the larger one are somewhat indistinct, and the skirts of both too opaque. It seems almost impossible in photography to attain Whistleresque subtleties of tone in a dark object. “Scurrying Home” is a landmark in the domain of camera art; and worth alone a trip to Europe. Many an artist after a three years’ sojourn abroad returns without being able to show half as much. “Scurrying Home” shows better than any other American photograph I know, the possibilities of artistic photography.

A “Winter Day,” a Fifth Avenue stage coach ploughing through chaotic masses of snow, is perhaps less pictorial from a painter’s point of view, but for that very reason more original and individual than the others, because it reminds one of nothing else, while most of the others suggest in some way or another faint reminiscences of some school of art. It is a realistic expression of an everyday occurrence of metropolitan life under special atmospheric conditions, rendered faithfully and yet with consummate art. I, as a literary man, would feel proud if I could express a “Winter Day” in words with the same vigor, correctness, and individual note as Mr. Stieglitz in his photographic plate. His achievements in this picture are not merely finger posts for amateur photographers, but for our American art world in general. 1.

1. Excerpt: “An Art Critic’s Estimate of Alfred Stieglitz” : Sadakichi Hartmann: In: The Photographic Times: June, 1898: pp. 259-262