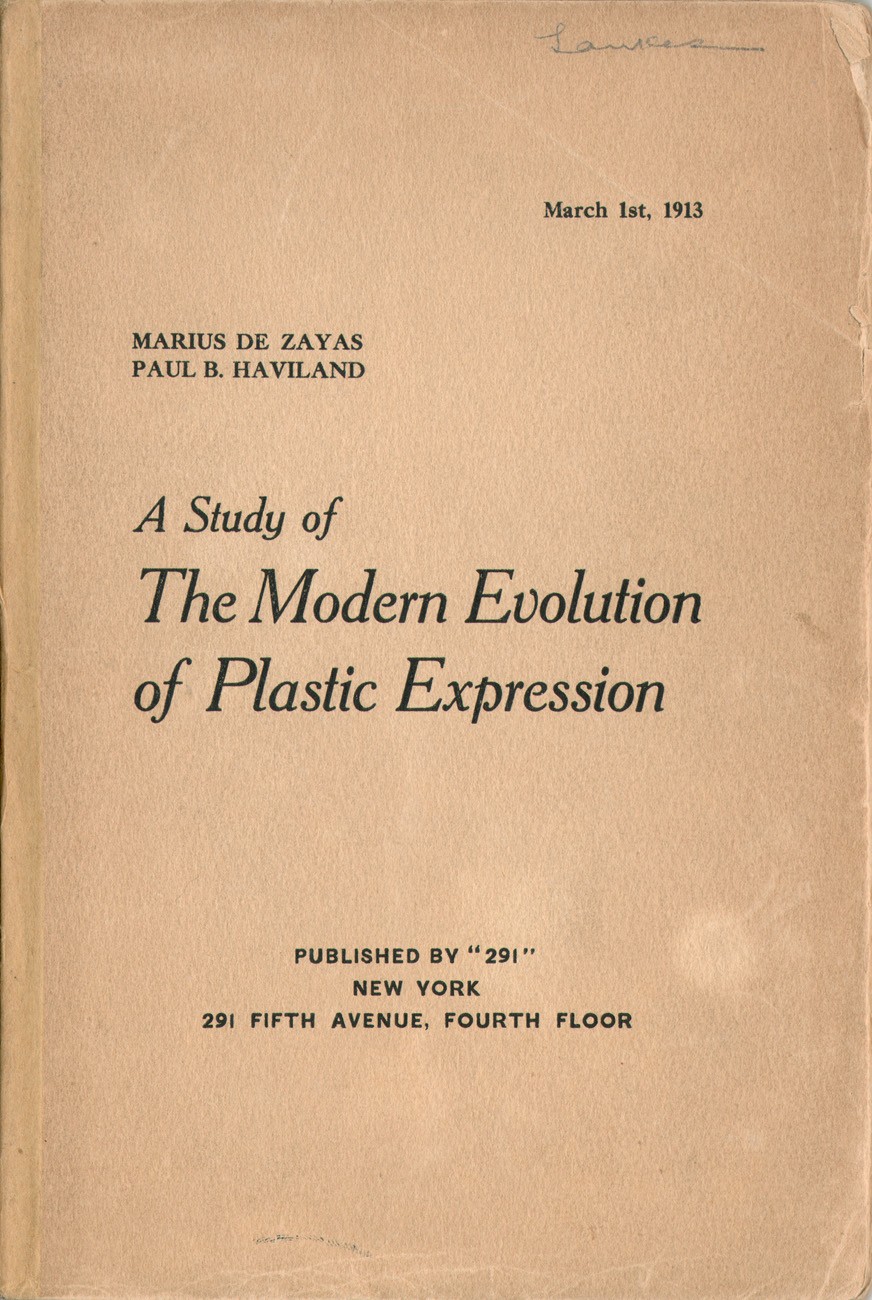

A Study of The Modern Evolution of Plastic Expression

This early treatise on the possibilities of personal artistic expression in relation to modern art was co-written by artist Marius De Zayas and photographer Paul Haviland and published by Alfred Stieglitz at his 291 gallery in New York City in 1913. The Metropolitan Museum of Art states this work was “published by the gallery with funds provided by Haviland. ”

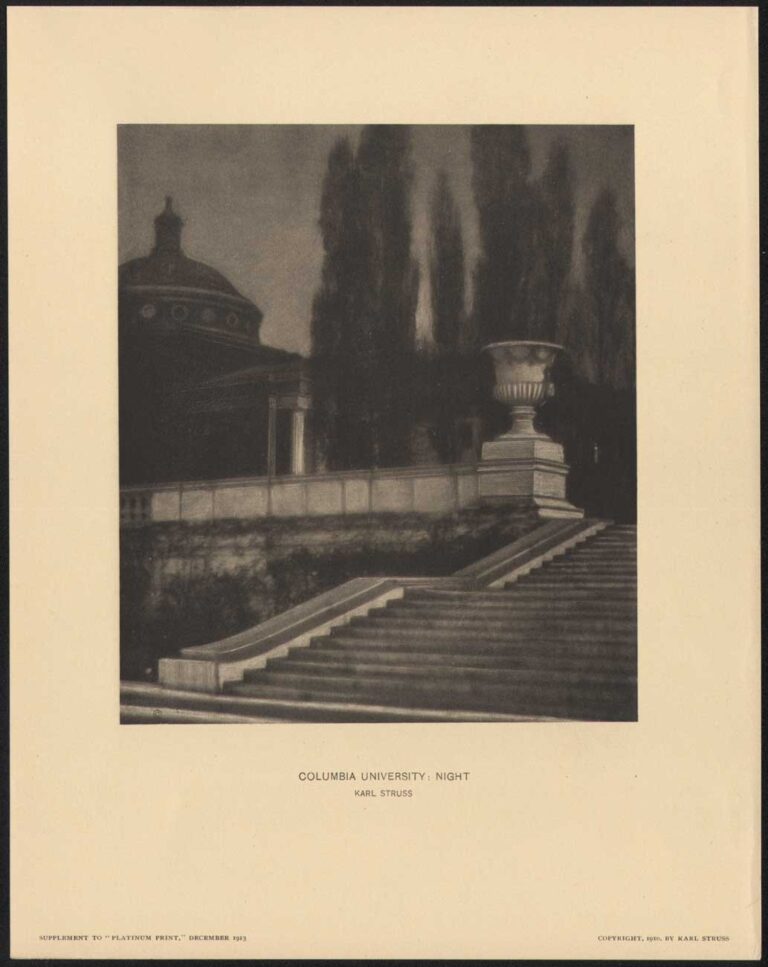

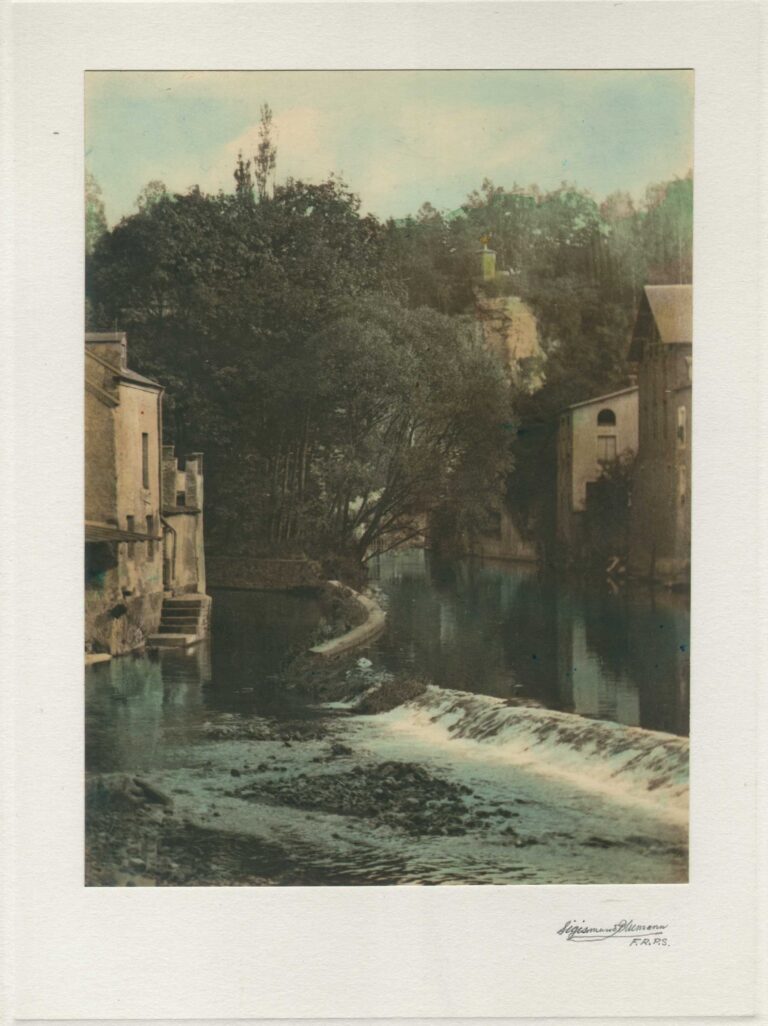

The essay runs from pages 9-36 and is followed by a series of small black and white halftone plates printed on glossy paper that are individually mounted. The plates in order of pagination: Les Joueurs de Cartes, by Paul Cézanne; Panel, by Henri Matisse; Portrait of M. Kahnweiler, by Pablo Picasso; Danseuse Etoile sur un Transatlantique, by François Picabia. The colophon page states:

One thousand copies of this booklet have been ordered printed Wednesday, February 26, 1913.

M. de Z. and P. B. H.

Printed by The Evening Post Job Printing Office, 156 Fulton St., N.Y.

This copy further embellished with a light, full-page impression woodcut known as Sundown in the rear of the volume by the important American woodcut artist Julius John Lankes (1884-1960) showing the figure of a man standing in a field with a hoe on his shoulder. This woodblock was most likely done later, sometime after 1917, when Lankes first started producing woodcuts. (1.) The booklet, with glued binding, is composed of leaves of Strathmore watermarked paper.

The following is the three-page introduction to the work in its’ entirety:

Beginning in the fall of 1905 with a series of exhibitions of Photographs in a little garret at 291 Fifth Avenue, New York City, a small nucleus of kindred spirits started for their own satisfaction a series of exhibitions at which the public was freely admitted. The main purpose of these exhibitions has at all times been to test the living value of examples of the work of certain men. The apparent issue, judging by the published criticisms, seems to have been whether the work shown was “art” or “personal expression” or what not. It matters little whether these questions are answered in the affirmative or in the negative. As a matter of fact there are some of those most vitally interested in the movement who hold that photography is not an art, and that neither, for that matter, is painting in its most advanced manifestations. But the essential point and that which gives them their claim to earnest consideration, however they may be classified, is that the works shown possess an element of life and are the logical and necessary outcome of conditions obtaining in our time.

The active workers of this association, headed by Alfred Stieglitz, have been brought and held together by an indomitable spirit of investigation. They have been inquisitive to the point of indiscretion, and childlike, when those in authority, those who know all that can be learned about art would tell them: “Don’t pay attention to this; this is not art;” they would answer: “but it interests me, I want to find out.” Their attitude may well be summed up in the following incident:

A well known collector and connoisseur, wandered into the little gallerie at “291” while the first exhibition of John Marin decorated the walls. After a rapid glance at the water colors he turned aggressively towards Alfred Stieglitz, and in a tone which admitted no contradiction: “This is not Art,” said he, “and I am supposed to know something about art.”—”Yes,” answered Stieglitz, unperturbed, “but you have finished your education, I am beginning mine.”

The main value of the exhibitions held at “291” has not been the mere gratification of a curiosity to see the work of artists who were beginning to play a role in the European Art World, or of artists who were struggling for recognition; it does not lie either in the fact that these artists were given an opportunity to reach the public.

The inestimable value of these exhibitions lies in the unique opportunity for serious and systematic study of modern expression. It lies in the subsequent discussions, in the analytical work which followed, in the experiments which they inspired. In short “291” is primarily a laboratory where the work presented is impartially analyzed, dissected, put through the severest tests for the purpose of finding out the truth whatever that truth may be and whatever results it may have. From common study of the work shown at “291”, and from independent study of the work of artists in Paris, and of the art of previous periods and different peoples, as well as from contributions in other sciences we have come to certain conclusions which we present here in the hope that they may help to a better understanding of modern plastic art.

In approaching the study of the modern evolution of expression let us forget what we know about art and all our prejudices and regard it merely as an expression of life through the activities of man. (2.)

marginalia: Lankes in graphite on cover; LANKES in ink on flypage.

1. The Woodcut Art of J.J. Lankes: Welford Dunaway Taylor: Imago Mundi: Jaffrey, N.H.: 1999: Chapter IV: p. 14. Sundown, along with Deserted House, were the first two woodcuts by Lankes to appear in print in the October, 1918 of The Liberator, a socialist magazine.

2. Foreword: A Study of The Modern Evolution of Plastic Expression: “291”: March 1, 1913: New York: pp. 5-7