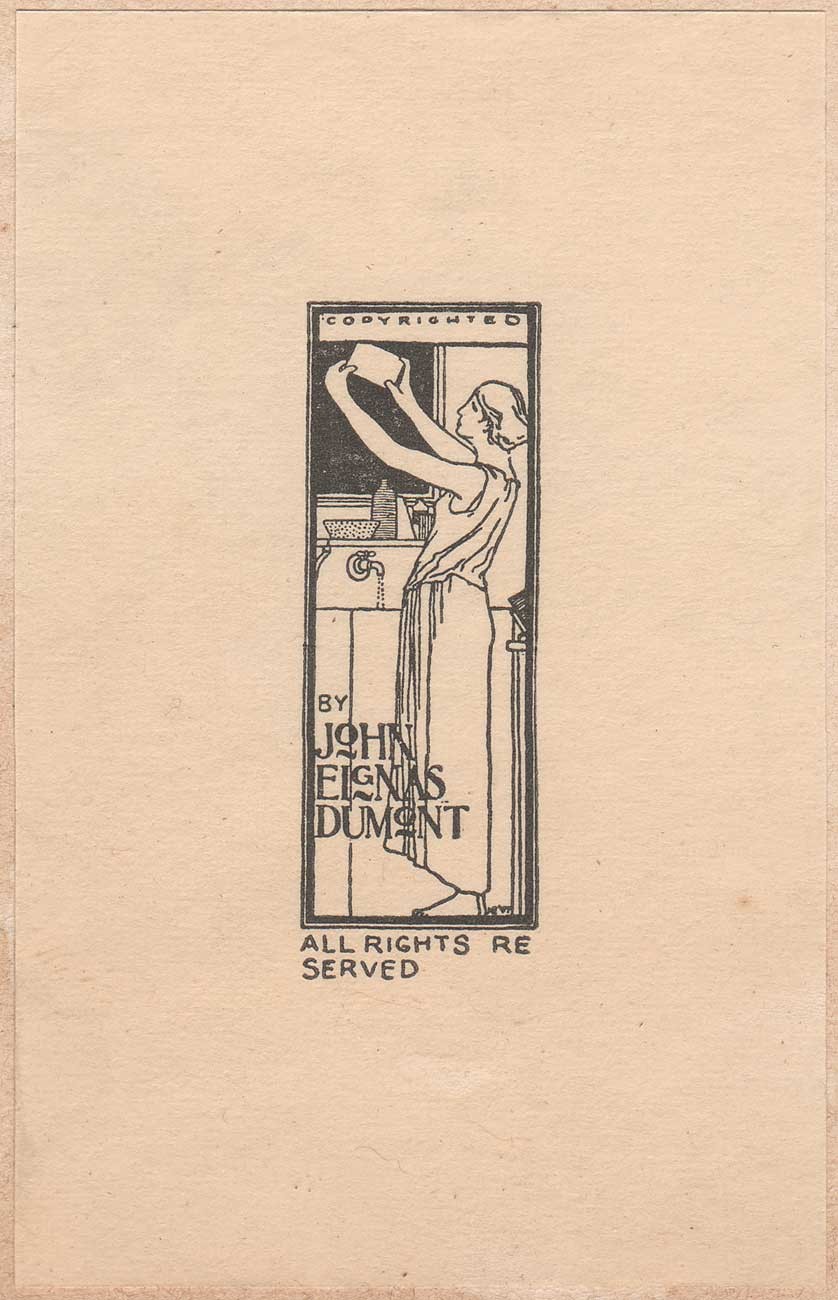

Harvey Ellis Copyright Label

Noted American artist, architect and designer Harvey Ellis (1852-1904) originally designed this label for American amateur photographer John E. Dumont in 1897 as an Ex Libris bookplate. This variant by Ellis was used by Dumont as a copyright protection label for his photographs. The designer made the change of expanding the width of the window pane at top margin of his design and inserting the word COPYRIGHTED for EX LIBRIS. The additional ALL RIGHTS RE

SERVED was further added outside the design’s double border frame on bottom margin.

This variant label was pasted to the verso of Dumont’s photograph The Dice Players which can be seen on the site at link below.

In 1899, a description of the original John Eignas Dumont Ex Libris book plate appeared in the London Journal of the Ex Libris Society:

DUMONT BOOK-PLATES.

By the kindness of a member we are enabled to give an illustration of the book-plate of Mr. John E. Dumont, of Rochester, N.Y., designed by Mr. Harvey Ellis, of the same city. Mr. Dumont is a leading photographer in America, and his works are well known in England. The plate represents the genius of photography surrounded by the accessories of the “dark room.” Mr. Ellis, the designer, is a prominent architect and a water-colour artist of repute. The plate, here given, is graceful in design and execution. (p. 128)

1908 assesment: Harvey Ellis

In 1908, the architect Hugh Mackie Gordon Garden (1873-1961) weighed in on the life and career of Ellis for the December, 1908 issue of The Architectural Review. Profusely illustrated with architectural and site drawings done during his career, the following is the first of his 3-page article:

Harvey Ellis, Designer and Draughtsman

It is almost impossible to write of the work of Harvey Ellis without some reference to his rainbow personality. Gifted in many directions far beyond most men, even beyond most men of marked success; fascinating in conversation, with a range of general information touching almost every phase of our activities; able to hold and enchant alike a company of scholars or of the rougher and “broader” element that is found on the seamy side of our Western city life, Harvey Ellis was a man of fine culture, an excellent designer — but not really an architect.

He was an artist and a romanticist, who loved to indulge his peculiar taste for life in the nearest and readiest direction, careless of results and apparently without any marked ambition. Although it is impossible to look at his ingenious and poetic drawings and designs, whether of architecture, decoration, or of sheer unbridled fancy, without knowing that he loved to draw, still he seems to have cared as much for mere talk, for teaching the young men who flocked around him and learned so much from him; or for any and all of the multitude of human relations that surround and distract the serious worker and are by serious workers relentlessly suppressed or avoided. Indeed, he seems to have drifted into the practice of architecture with little, if any, special preparation, merely as the easiest method, for him, of keeping body and soul together, and he would perhaps have made as great a success (or failure) in any one of a dozen different directions; particularly, of course, those which open to men of artistic insight and invention. But he cared as much or more for the myriad activities that are by the industrious ones of this world grouped under the all-inclusive term of “idleness.”

A glutton for work when it had to be done, he was nevertheless incredibly lazy. The greater the task, the faster flew his nimble wits and fingers; always with the desire to have done and get back to the paths of his restless and insatiable fancy. Careless of methods and prodigal of his resources, he would sit and talk interminably if any one would listen — listening was always well worth while. He poured himself out, and cared nothing for the reward or the consequences. Necessarily, in a world given over to more conventional and tractable ways, he did not always meet with the smile of approval, and perhaps, therefore, he was not often happy; but, nevertheless, his was a fine, expansive nature and one for which those who knew him are the richer. If he were ambitious, then he sacrificed his opportunities —— and opportunity pursued him.

He measured himself repeatedly in competition against the great ones of his profession, and often won; but the fire always burned out before the task was finished, and his executed buildings are uniformly disappointing. In speaking of his work it is entirely fair to ignore those who employed him, for the indelible Ellis touch is on it all, and nowhere is there evidence of any guiding or restraining hand.

His architectural designs are generally reminiscent. He usually picked up some suggestion, generally medieval, from some picture or photograph and twisted it to suit his own purpose; and he did not care greatly for its entire suitability or logical fitness, so long as it served him to make a pleasant pictorial composition —— and that, as you may know, is not the way of the serious architect. Indeed, it is almost a pity that he dabbled in architecture at all, in spite of his many beautiful drawings, for as a painter and draughtsman he would have ranked far higher. Upon the rare occasions when he contributed pictures—generally water-colors—to the big exhibitions he invariably commanded attention; for he had a style absolutely personal and distinct, combining delicacy with strength and a finished and individual technique. He was a master of composition, both in his drawings and in his designs of buildings, and probably no one of his time approached so closely to Richardson in the quality of his work as Ellis did. Indeed, the so-called Romanesque revival which Richardson rediscovered for America owes much of what was best in it to Ellis. His quality, however, is less Titanic than Richardson’s, less powerful, and more human. Had he survived to these days, when the Romanesque is again quite dead and gone, we should have seen a new Ellis; for he was adaptable and original, … (1.) (article continues from pp. 185-86)

1. Hugh M. G. Garden: The Architectural Review: Boston: Dec., 1908 p. 184